Abstract

Background:

Advance care planning is seen as an important strategy to improve end-of-life communication and the quality of life of patients and their relatives. However, the frequency of advance care planning conversations in practice remains low. In-depth understanding of patients’ experiences with advance care planning might provide clues to optimise its value to patients and improve implementation.

Aim:

To synthesise and describe the research findings on the experiences with advance care planning of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness.

Design:

A systematic literature review, using an iterative search strategy. A thematic synthesis was conducted and was supported by NVivo 11.

Data sources:

The search was performed in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL on 7 November 2016.

Results:

Of the 3555 articles found, 20 were included. We identified three themes in patients’ experiences with advance care planning. ‘Ambivalence’ refers to patients simultaneously experiencing benefits from advance care planning as well as unpleasant feelings. ‘Readiness’ for advance care planning is a necessary prerequisite for taking up its benefits but can also be promoted by the process of advance care planning itself. ‘Openness’ refers to patients’ need to feel comfortable in being open about their preferences for future care towards relevant others.

Conclusion:

Although participation in advance care planning can be accompanied by unpleasant feelings, many patients reported benefits of advance care planning as well. This suggests a need for advance care planning to be personalised in a form which is both feasible and relevant at moments suitable for the individual patient.

Keywords: Advance care planning, terminal care, palliative care, review

What is already known about the topic?

Advance care planning is seen as an important strategy to improve communication and the quality of life of patients and their relatives, particularly at the end of patients’ lives.

Despite an increasing interest in advance care planning, the uptake in clinical practice remains low.

Understanding of patients’ actual experiences with advance care planning is necessary in order to improve its implementation.

What this paper adds?

Although patients experience ambivalent feelings throughout the whole process of advance care planning, many of them report benefits, in particular, in hindsight.

‘Readiness’ is necessary to gain benefits from advance care planning, but the process of advance care planning itself could support the development of such readiness.

Patients need to feel comfortable in being open about their goals and preferences for future care with family, friends or their health care professional.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

In the context of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness, personalised advance care planning, which takes into account patients’ needs and readiness, could be valuable in overcoming challenges to participating in it.

Further research is needed to determine the benefits of advance care planning interventions for the care of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness.

Background

The growing interest in advance care planning (ACP) has resulted in a variety of ACP interventions and programmes.1 Most definitions of ACP incorporate sharing values and preferences for medical care between the patient and health care professionals (HCPs), often supplemented with input from and involvement of family or informal carers. Differences are seen in whether ACP focuses only on decision-making about future medical care or also incorporates decision-making for current medical care. Furthermore, there are different interpretations about for whom ACP is valuable, ranging from the general population towards a more narrow focus on patients at the end of their lives.2–5 A well-established definition of ACP is presented in Box 1.3

Box 1.

ACP refers to the whole process of discussion of end-of-life care, clarification of related values and goals, and embodiment of preferences through written documents and medical orders. This process can start at any time and be revisited periodically, but it becomes more focused as health status changes. Ideally, these conversations occur with a person’s health care agent and primary clinician, along with other members of the clinical team; are recorded and updated as needed; and allow for flexible decision making in the context of the patient’s current medical situation.3

ACP is widely viewed as an important strategy to improve end-of-life communication between patients and their HCPs and to reach concordance between preferred and delivered care.6–8 Moreover, there is a high expectation that ACP will improve the quality of life of patients as well as their relatives as it might decrease concerns about the future.1 Other potential benefits, which have been reported, are that ACP allows patients to maintain a sense of control, that patients experience peace of mind and that ACP enables patients to talk about end-of-life topics with family and friends.9–13

Despite evidence on the positive effects of ACP, the frequency of ACP conversations between patients and HCPs remains low in clinical practice.14–18 This can partly be explained by patient-related barriers.9,11,13,19,20 Patients, for instance, indicate a reluctance to participate in ACP conversations because they fear being confronted with their approaching death; they worry about unnecessarily burdening their families and they feel unable to plan for the future.9,11,13,19,20 In addition, starting ACP too early may provoke fear and distress.21 However, current knowledge of barriers to ACP is initially derived from patients’ responses to hypothetical scenarios or from studies in which it remains unclear whether patients really had participated in such a conversation.9,11,13,15,19,20 More recent research has shifted towards studies on the experiences of patients who actually took part in an ACP conversation. These studies can give a more realistic perspective and a better understanding of the patients’ position when having these conversations.

To our knowledge, there is only one review that summarises the perceptions of stakeholders involved in ACP and which includes some patients’ experiences. However, this review is limited to oncology.21 Given the fact that ACP may be of particular value for patients with a progressive disease due to the unpredictable but evident risk of deterioration and dying,2,22,23 this study focuses on the experiences of the broader population of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting disease with ACP.

We aim to perform a systematic literature review to synthesise and describe the research findings concerning the experiences of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness who participated in ACP. Our analysis provides an in-depth understanding of ACP from the patients’ perspective and might provide clues to optimise its value to patients.

Method

Design

A systematic literature search was conducted, the analysis relying on the method of thematic synthesis in a systematic review.24

Search strategy

In collaboration with the Dutch Cochrane centre, we used a recently developed approach that is particularly suited to systematically review the literature in fields that are challenged by heterogeneity in daily practice and poorly defined concepts and keywords, such as the field of palliative care.25 The literature search strategy consisted of an iterative method. This method has, like all systematic reviews, three components: formulating the review question; performing the literature search and selecting eligible articles. The literature search, however, consists of combining different information retrieval techniques such as contacting experts, a focussed initial search, pearl growing26,27 and citation tracking.25,27 These techniques are repeated throughout the process and are interconnected through a recurrent process of validation with the use of so-called ‘golden bullets’. ‘Golden bullets’ are articles that undoubtedly should be part of the review and are identified by the research team in the first phase of the search (phase question formulating). These ‘golden bullets’ are used to guide the development of the search string and to validate the search.

First, we undertook an initial search in PubMed and asked an internationally composed set of experts, who are actively involved in research and practice of ACP (n = 33) to provide articles that in their opinion, should be part of this review. These articles were used to refine the eligibility criteria. Based on these refined criteria, the ‘golden bullets’ (n = 7)28–34 were selected from the articles identified from the initial search and by the experts. Second, the analysis of words used in the title, abstract and index terms of the ‘golden bullets’ were used to improve the search string. A new search was then conducted. The validation of this search was carried out by identifying whether all the ‘golden bullets’ were retrieved in this search. Not all ‘golden bullets’ could be identified in the retrieved citations after this first search. Therefore, the search string was adjusted several times and the process of searching and validation was repeated until the validation test was successful. Once the validation test was successful, the final search was carried out on 7 November 2016 using four databases namely MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase Classic & Embase, PsycINFO (Ovid) and CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (see Table 1 for search terms). Finally, the reference list of all included articles was cross referenced in order to identify additional relevant articles.

Table 1.

Database search strategy.

| Database | Keywords |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | ((qualitative or focus group* or case stud* or field stud* or interview* or questionnaire* or survey* or ethnograph* or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative* or (life and (history or stor*)) or verbal interaction* or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct* or purposive sampl* or phenomenol* or criterion sampl* or ‘story telling’ or (case adj (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’).ti,ab,kf. OR (conversation adj2 analys*).ti,ab,kf. OR qualitative research/ or exp questionnaire/ or self report/ or health care survey/ or ‘nursing methodology research’/ or ‘Interviews as Topic’/) AND (exp advance care planning/ OR ((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care adj3 planning)).ti,ab,kf.) |

| Embase Classic & Embase | (qualitative or focus group$ or case stud$ or field stud$ or interview$ or questionnaire$ or survey$ or ethnograph$ or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative$ or (life and (history or stor$)) or verbal interaction$ or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct$ or purposive sampl$ or phenomenol$ or criterion sampl$ or ‘story telling’ or (case adj (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’ or (conversation adj2 analys*)).ti,ab,kw,hw. exp qualitative research/data collection method/ or exp interview/ or exp questionnaire/ health care survey/self-report/nursing methodology research/exp ethnography/discourse analysis/((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care adj3 planning)).ti,ab,kw,hw. |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | (qualitative or focus group$ or case stud$ or field stud$ or interview$ or questionnaire$ or survey$ or ethnograph$ or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative$ or (life and (history or stor$)) or verbal interaction$ or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct$ or purposive sampl$ or phenomenol$ or criterion sampl$ or ‘story telling’ or (case adj (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’ or (conversation adj2 analys*)).ti,ab,id,hw. ‘Consumer Opinion & Attitude Testing’.cw. exp Questionnaires/exp Self Report/exp Surveys/exp Ethnography/exp Grounded Theory/exp Phenomenology/qualitative research/ or exp interviews/ or observation methods/((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care adj3 planning)).ti,ab,hw,id. |

| Cinahl search (EBSCOhost) | SU ((qualitative or focus group* or case stud* or field stud* or interview* or questionnaire* or survey* or ethnograph* or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative* or (life and (history or stor*)) or verbal interaction* or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct* or purposive sampl* or phenomenol* or criterion sampl* or ‘story telling’ or (case N1 (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’) OR (conversation N2 analys*)) AB ((qualitative or focus group* or case stud* or field stud* or interview* or questionnaire* or survey* or ethnograph* or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative* or (life and (history or stor*)) or verbal interaction* or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct* or purposive sampl* or phenomenol* or criterion sampl* or ‘story telling’ or (case N1 (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’) OR (conversation N2 analys*)) TI ((qualitative or focus group* or case stud* or field stud* or interview* or questionnaire* or survey* or ethnograph* or grounded theory or action research or ‘participant observation’ or narrative* or (life and (history or stor*)) or verbal interaction* or discourse analysis or narrative analysis or social construct* or purposive sampl* or phenomenol* or criterion sampl* or ‘story telling’ or (case N1 (study or studies)) or ‘factor analysis’ or ‘self-report’) OR (conversation N2 analys*)) (MH ‘Qualitative Studies +’)(MH ‘Clinical Assessment Tools +’) OR (MH ‘Questionnaires +’) OR (MH ‘Interview Guides +’)(MH ‘Surveys’)(MH ‘Interviews +’)(MH ‘Self Report’)(MH ‘Advance Care Planning’) TI((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care N3 planning)) AB((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care N3 planning)) SU((advance adj preferences) or ‘advance care planning’ or advance directive* or living will* or end-of-life planning or (future care N3 planning)) excluding MEDLINE records |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers were included based on the following inclusion criteria: the study must be an original empirical study; published in English; it must concern patients diagnosed with a life-threatening (illnesses for which curative treatment may be feasible but can fail)35 or a life-limiting illness (illnesses for which there is no reasonable hope of cure)36 and report experiences of patients who actually participated in ACP. We considered an activity to be ACP when it concerned a conversation which at least aimed at clarifying patients’ preferences, values and/or goals for future medical care and treatment. This conversation could have been conducted either by an HCP, irrespective of whether they were involved in the regular care for that particular patient or by persons who are not directly related to the patients’ care setting.

Studies reporting the experiences of multiple actors were excluded when the patients’ experiences could not be clearly distinguished. Studies in which only a part of the respondents had participated in ACP were also excluded when their experiences could not be distinguished from those patients who did not participate in ACP. Because of the difficulty of assessing the level of competence of the respondents, it was decided to exclude studies focussing on children aged under 18 and patients with dementia or a psychiatric illness.

Search outcomes

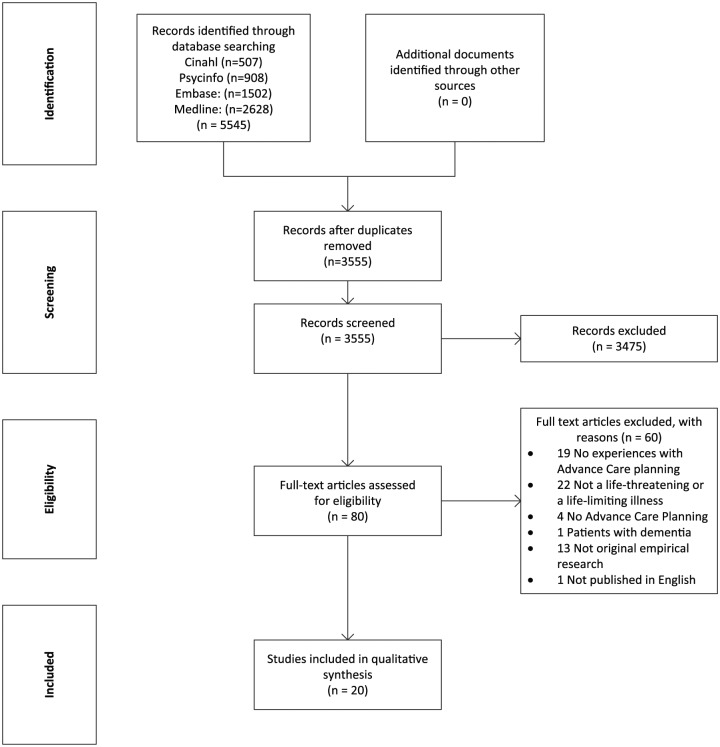

We identified 3555 unique papers. Two researchers (M.Z., L.J.J.) independently selected studies eligible for review based on the title and abstract using the inclusion criteria. Thereafter, the full text of the remaining studies (n = 80) was reviewed (M.Z., L.J.J.). The researchers discussed any disagreements until they achieved consensus. Remaining disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third researcher (M.C.K.). Finally, 20 articles were found to meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The web-based software platform Covidence supported the selection process.37

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the inclusion of articles for this review.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the qualitative studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist,38 a commonly used tool in qualitative evidence syntheses.39 The CASP checklist consists of 10 questions covering the aim, methodology, design, recruitment strategy, data collection, relationship between researcher and participants, ethical issues, data analysis, findings and value of the study.38 A ‘yes’ was assigned when the criterion had been properly described (score 1), a ‘no’ when it was not described (score 0) and a ‘can’t tell’ when the report was unclear or incomplete (score 0.5). Total scores were counted ranging from 0 to 10. We considered a score of at least 7 as indicating satisfying quality.

The methodological quality of mixed-method studies was assessed using the multi-method assessment tool developed by Hawker et al.40 This tool consists of nine categories: abstract and title; introduction and aims; method and data; sampling; data analysis; ethics and bias; results; transferability or generalisability; and implications. Each category was scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1–4, resulting in a total score from 9 (very poor) to 36 (good). We consider a score of at least 27 (=fair) as indicating satisfactory quality.

Two authors (M.Z., L.J.J.) independently assessed all included articles. Discrepancies were encountered in 33 of the 190 items assessed with the CASP and in 3 of the 9 items assessed with the Hawker scale. These were resolved by discussion.

The mean score of the methodological quality of the qualitative studies 28–34,41–52, according to the CASP, was 8 out of 10 (range: 6.5–9.5). Main issues concerned limitations describing ethical issues 30,33,34,41–45,47,49,51,52 and the lack of information concerning the relationship between researchers and respondents 28–30,32–34,41,42,44,46–50,52 (Table 2). The quality of the mixed-method study53 was 29 (out of 36) according to the scale of Hawker (Table 3).40 Points were in particular lost in the categories ‘method and data’ and ‘data analysis’.

Table 2.

Quality assessment CASP.

| Aim | Methodology | Design | Recruitment | Data collection | Relationship | Ethical | Data analysis | Finding | Values | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdul-Razzak et al.28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 9 |

| Almack et al.29 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 8 |

| Andreassen et al.41 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 7 |

| Bakitas et al.42 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 7.5 |

| Barnes et al.43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 8.5 |

| Brown et al.44 | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 7 |

| Burchardi et al.45 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 8.5 |

| Burge et al.30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 7.5 |

| Chen and Habermann46 | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 7.5 |

| Epstein et al.47 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 8.5 |

| Horne et al.32 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 8 |

| MacPherson et al.31 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 9.5 |

| Martin et al.34 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 8.5 |

| Metzger et al.48 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | No | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 8 |

| Robinson49 | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 6.5 |

| Sanders et al.50 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 9 |

| Simon et al.51 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | Yes | Valuable | 9 |

| Simpson52 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | No | Yes | Valuable | 6.5 |

| Singer et al.33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | No | Can’t tell | Yes | Yes | Valuable | 8 |

Table 3.

Quality assessment Hawker.

| Michael, et al.53 | |

|---|---|

| Abstract and title | 3 |

| Introduction and aims | 3 |

| Method and data | 3 |

| Sampling | 4 |

| Data analysis | 3 |

| Ethics and bias | 3 |

| Results | 3 |

| Transferability or generalisability | 4 |

| Implications and usefulness | 3 |

| Total | 29 |

4: Good; 3: fair; 2: poor; 1: very poor.

The appraisal scores are meant to provide insights into the methodological quality of the included studies. They were not used to exclude articles from the systematic review because a qualitative article with a low score could still provide valuable insights and thus be highly relevant to the study aim.54,55

Data extraction and analysis

To achieve the aim of this systematic review, information was extracted on general study characteristics and the patients’ experiences and responses (Table 4). To provide context and to facilitate the interpretation of the results, the number of patients refusing participation in the study and the number of dropouts were identified, as well as the underlying reasons. This process was undertaken and discussed by two authors (M.Z., L.J.J.). Disagreements remained on three papers28,31,46 and were resolved in discussion with a third author (M.C.K.).

Table 4.

Extraction data form.

| Reference | Country | Aim | Method | Sample | Intervention/setting | Data collection | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdul-Razzak et al.28 | CA | To understand patient perspectives on physician behaviours during EOL communication | Qualitative study | Seriously ill hospitalised patients (cancer and non-cancer) with an estimated 6–12 month mortality risk of 50% (n = 16) | Experiences with EOL communication in regular care, including ACP, in the moment decision-making and related information sharing processes | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Two types of HCP behaviour were felt to be beneficial during EOL communication. (1) ‘Knowing me’ relates to the importance of the family involvement during the EOL conversation by the HCP and the social relationship between the patient and the HCP. (2) ‘Conditional candour’, relates to the process of information sharing between the HCP and the patient including an assessment of the patients’ readiness to participate in an EOL conversation |

| Almack et al.29 | UK | To explore the factors influencing if, when and how ACP takes place between HCP’s, patients and family members from the perspectives of all parties involved and how such preferences are discussed and are recorded | Qualitative study | Patients from palliative care register (cancer and non-cancer) and who were expected to die in the next year according to the HCP (n = 18) | Experiences with ACP in regular care (focus on Preferred Place of Care tool) | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 9 out of 13 cancer patients had a degree of open awareness, of which three patients had some preferences recorded in a written document. A few patients had initial conversations about future plans, but did not revisit these over time. When an HCP initiated an EOL conversation, patients wondered if they were close to dying. Patients who felt relatively better, were reluctant to participate in an ACP conversation |

| Andreassen et al.41 | DK | To explore nuances in long-term impact of ACP as experienced by patients and relatives | Qualitative study | Patients with a life-limited disease (n = 3) and relatives (n = 7) | An ACP discussion in research context | Semi-structured face-to-face and phone interviews | ACP impacted patients and relatives in three ways. (1) Positive impact, such as better communication; awareness of dying and empowerment. (2) No impact, described as ACP being insignificant and not relevant yet. (3) Negative impact, less communication about the EOL |

| Bakitas et al.42 | USA | To elicit patient and caregiver participants’ feedback on the clarity and overall usefulness of the commercially available PtDA when introduced soon after a new diagnosis of advanced cancer | Qualitative study | Patients with an advanced solid tumour or haematological malignancy (prognosis between 6 and 24 months) (n = 57 patients, n = 20 caregivers) | Looking ahead: Choices for Medical Care When You’re seriously Ill patient decision aid (PtDA) | Semi-structured phone interviews | Patients who participated in the programme ‘Looking ahead’ felt empowered, informed and ‘in charge’. Patients needed to be ready to participate in this programme. Some patients had felt not ready before the start, but in hindsight mentioned that it was the right time. After the programme some patients started to talk with their healthcare proxy or their HCP |

| Barnes et al.43 | UK | To inform the nature and timing of an ACP discussion intervention delivered by an independent trained mediator | Qualitative study | Patients with clinically detectable, progressive disease (n = 40) | An ACP intervention: ACP discussions with a trained planning mediator using a standardised topic guide. All patients received up to three sessions | Verbatim transcripted audio-tapes of the face-to-face ACP intervention | A third of the patients said the ACP discussion had been helpful and thought-provoking. Many patients found the information valuable, and some found it challenging to think about dying. A few patients talked with their family about their future, some patients did not want to burden or upset their relatives, and others were not yet ready to discuss this topic with family or the HCP. Over a third of the patients said their doctors were reluctant to introduce such topics |

| Brown et al.44 | AU | To explore issues relating to EOL decisions and ACP | Qualitative study | Patients with advance COPD (GOLD stage IV) (n = 15) | Experiences in regular care with ADs and ACP in regular care | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 2 of the 15 patients had conversations with their HCP about CPR. One couple completed an AD and was well informed about future decision-making. Some patients talked with their family about their wishes and appointed a decision-maker. Others did not because of the feeling that the family would feel uncomfortable to make a decision |

| Burchardi et al.45 | DE | To investigate how neurologists provide information about LWs to ALS patients and to explore if their method of discussing it met the patients’ needs and expectations | Qualitative grounded theory study | ALS patients (n = 15) | Experiences with LW in regular care | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 6 out of 15 ALS patients completed a LW, mostly after symptoms had worsened. Patients described ADs as important and necessary, but they also considered ADs as closely connected to forthcoming death. The patients preferred information given in a way that would minimise the anxiety. Some patients felt that an LW is contrary with the work of an HCP. Family involvement was by some described as a process of discussion and coping, which led to completing an LW. Others only gave a copy of the LW |

| Burge et al.30 | AU | To evaluate the introduction of a structured ACP information session from the perspective of participants in PR&M programmes | Qualitative study | Patients having chronic respiratory impairment, in PR&M (n = 67) | A structured group ACP information session presented by two trained facilitators | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 17 patients described the PR&M programme as an appropriate place to receive information about ACP. Participants valued the received information and highlighted the importance of the educator. 24 patients started to think about their personal decision-making and initiated a discussion with family members |

| Chen and Habermann46 | USA | To explore how couples living with advanced MS approach planning for future health changes together | Qualitative study | Patients with advanced MS and their caregiver spouses (n = 20) | Experiences with ACP among couples | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 3 out of 10 couples with advanced MS had an AD or LW and communicated their wishes to their loved ones. These MS couples felt confident in knowing each other’s wishes. Most couples had some thoughts about aspects of ACP, but had not a written AD. Expressed difficulties were to make a choice, communication and the hope for a cure |

| Epstein et al.47 | USA | To better understand the more general problem, and potential solutions to, barriers to communicate about EOL care | Qualitative study | Patients with advanced hepatopancreatico-biliary cancers (n = 54) (n = 26 articulated questions or/and comments) | One-time educational video or narrative about CPR | Face-to-face open interview following the intervention | Video education was seen by patients as an appropriate means of starting an ACP conversation. ACP should start early because it is better to discuss these topics when you are reasonably healthy. Patients found ACP sometimes difficult to discuss, but they considered it as important. The information was helpful and HCPs should be involved in ACP in order to realise life goals and to plan practically |

| Horne et al.32 | UK | To develop and pilot an ACP intervention for lung cancer nurses to use in discussing EOL preferences and choices for care with patients diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer | Qualitative grounded theory study | Patients with inoperable lung cancer (n = 9) and their family members (n = 6) | An ACP discussion with a trained lung cancer nurse using an ACP interview guide, an ACP record and an ACP checklist | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Most participants reported that they felt better after the ACP discussion. Nursing attributes enabled patients to talk about EOL issues. Some patients found it a ‘personal thing’ to discuss ACP with the nurse. Patients appreciated the information they received and accepted the recording of their preferences. These were shared with the HCP and sometimes with family |

| MacPherson et al.31 | UK | To answer whether people with COPD think that ACP could be a useful part of their care, and to explore their reasoning behind this view, as well as their thoughts about future and any discussions about future care that had taken place | Qualitative grounded theory study | Patients with severe COPD (n = 10) of these two respondents reported experiences with ACP | Experiences with ACP in regular care | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 2 out of 10 patients reported some discussion about future care. These discussions initially upset them. This was caused by being unfamiliar with ACP, and the exploration of the patient’s prognosis led the patient to think more about mortality. Patients felt uncomfortable documenting their wishes |

| Martin et al.34 | CA | To develop a conceptual model of ACP by examining the perspectives of individuals engaged in it | Qualitative grounded theory study | Patients with HIV or AIDS (n = 140) | An educational video with a generic centre for bioethics LW or the disease-specific HIV LW or both ADs | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | ACP was seen as confronting, but helpful. It helped patients to prepare to face death and helped them to confront and to accept the prospect of their death. Patients mentioned that they learned more about themselves and achieved feelings of ‘peace’. Both ACP and an AD provided a language and framework that can help to organise patients’ thoughts about their preferences for care, thus enabling a degree of control. ACP strengthened relationships with patients’ loved ones |

| Metzger et al.48 | USA | To increase the understanding of patients’ and surrogates’ experiences of engaging in ACP discussions, specifically how and why these discussions may benefit patients with LVADs and their families | Qualitative study | Patients with an LVAD (n = 14) and their surrogates (n = 14) | An ACP intervention: SPIRIT-HF | Semi-structured phone interviews | 3 themes were identified. (1) Nearly all patients reported that sharing their heart failure stories was a positive and essential part of SPIRIT-HF. (2) SPIRIT-HF brought patients an increased peace of mind. It allowed patients to clarify their wishes which created a feeling of being more prepared for the future. (3) ACP discussions should be an individual approach, the best timing may vary |

| Michael et al.53 | AU | To assess the feasibility and acceptability of an ACP intervention | Mixed methods study (qualitative grounded theory study) | Patients with cancer stage III/IV (n = 30) | A 5-step guided ACP intervention | Questionnaire and semi-structured face-to-face interviews | This ACP intervention may motivate participants to consider thoughts about their future health care. Many patients said that the intervention helped them to feel respected, heard, valued, empowered and relieved. The intervention was both informative and distressing. Most patients welcomed the opportunity to involve their family during this conversation. A barrier to complete a written document was, e.g. not feeling ready |

| Robinson49 | CA | To explore the applicability and usefulness of a promising ACP intervention and examined the ACP process | Qualitative study | Patients newly diagnosed with advanced lung cancer (n = 18) and their loved one | RC tool | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | The RC tool was addressed as difficult, but helpful. ACP is a family affair. Patients wanted to avoid burdening their family and they felt safe knowing that their wishes were clearly understood by a trusted loved one. ACP brought an enhanced sense of closeness. None of the patients had involved a HCP |

| Sanders et al.50 | UK | To examine the impact of incorporating the subject of planning for death and dying within self-management intervention | Qualitative study | Patients with a long-term health condition (n = 31) and patients with HIV (n = 12) | Education group session about ACP within a much wider generic ‘expert patient’ course designed to teach people how to manage a long-term health condition | Semi-structured interviews | A group educational session is a valuable form of social support. However, the session about LWs was disruptive, and the introduction of the educational material was confrontational. One patient said that it was traumatic, but relevant. Some patients thought that talking about LWs would be more acceptable for older people with chronic conditions or people with a terminal illness |

| Simon et al.51 | CA | To explore and understand what it is like to go through an ACP process as a patient | Qualitative grounded theory study | Patients with end-stage renal disease who had completed a health region quality initiative, pilot project of facilitated ACP (n = 6) | RC tool | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Patients addressed ACP as logical. One patient described an initial shock when being invited. One felt it was: ‘a positive thing: peace of mind’ which contained three categories.(1) Witnessing an illness in oneself or in others and acknowledging mortality; (2) I don’t want to live like that or to be a burden to oneself or others and (3) the process. The awareness of the EOL allowed patients to participate in ACP, the workbook was viewed as central to discussions and the facilitator was seen as a paperwork reviewer. Some patients initiated a discussion with an HCP |

| Simpson52 | CA | To give insights into what is required for a meaningful, acceptable advance care planning in the context of advance COPD | Qualitative research methodology | Patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD in an advance stage (n = 8) and their informal caregivers (n = 7) | Loosely structured conversations with the help of the brochure ‘Patient and Family Education Document’: Let’s Talk About ADs including an AD template | An open interview | Despite the initial resistance of patients to participate in the ACP conversation, positive outcomes of ACP occurred. ACP with a facilitator was an opportunity to learn about several factors. These included: the options for EOL care; considering or documenting EOL care preferences so the decision-maker would offer tangible guidance; countering the silence around the EOL through social interaction; and sharing concerns about their illness with the HCP |

| Singer et al.33 | CA | To examine the traditional academic assumptions by exploring ACP from the perspective of patients actively participating in the planning process | Qualitative grounded theory study | Patients who are undergoing haemodialysis (n = 48) | An educational video about ADs and patients receive an AD form | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Through the use of open communication, ACP is a helpful means of preparing for incapacity and death. Resulting in peace of mind. The awareness of life’s frailty allowed patients to participate in ACP. ACP is based on autonomy, maintaining control and relieve of the burden on the loved ones. The result of ACP is not simply to complete an AD; the discussion about the patient’s wishes is also meaningful in itself |

ACP: advance care planning; AD: advance directive; AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; AU: Australia; CA: Canada; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DE: Germany; DK; Denmark; EOL: end-of-life; GOLD: global initiative for obstructive lung disease; HCP: healthcare professional; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PtDA: patient decision aid; LVAD: left ventricular assist device; LW: living wills; MS: multiple sclerosis; PR&M: pulmonary rehabilitation and maintenance; PtDA: patient decision aids; RC: respecting choice; SPIRIT-HF: ‘Sharing the Patient’s Illness Representations to Increase Trust in Heart Failure’; UK: United Kingdom.

The thematic synthesis consisted of three stages.24 By using the software programme for qualitative analysis, NVivo 11, a transparent link between the text of the primary studies and the findings was created. First, the relevant fragments, with respect to the focus of this systematic review, were identified and coded. Second, the initial codes were clustered into categories and the content of these clusters was described. Finally, the analytical themes were generated.24 This analysis was performed by the first author (M.Z.) in collaboration with the last author (M.C.K.).

Results

Study characteristics

Of the 20 articles selected,28–34,41–53 19 had a qualitative study design 28–34,41–52 and one a mixed-methods design.53 All included studies were conducted in Western countries, mostly in Canada (n = 6) (Table 4).28,33,34,49,51,52 The studies included patients with cancer 28,29,32,42,43,47,49,53 as well as patients with other life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)31,44,52, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)34,50, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS))45 (Table 4).28–31,33,34,41,43,44,46,48–52 Most studies reported the experiences of patients in an advanced stage of their illness.28,29,32,41–44,46–49,51–53 A total of 14 studies reported patients’ experiences with an ACP intervention in a research context,30,32–34,41–43,47–53 the remaining six articles focussed on ACP experiences in daily practice (Table 4). 28,29,31,44–46The studies labelled the conversations as ACP conversations29–34,41–53(n = 19) or as end-of-life conversations (n = 1).28

Eight studies reported the number of refusals and/or the reasons why patients refused to participate in the study.30,31,33,34,42,45,51,53 The total number of eligible patients in these eight studies was 579, of which 206 patients refused to participate. Patients refused for ‘practical’ reasons (n = 44)30,42 or felt too ill to participate (n = 42).33,34,53 Other reasons concerned logistics (e.g. could not be reached by phone; n = 42)33,42,45,51,53 and some patients (n = 25) died during the period of recruitment.33–45 Eleven patients (5%) were reported to have refused because they felt not ready to participate or were too upset by the word ‘palliative’.31,53 The number of dropouts remained unclear. Three studies reported reasons for drop out 29,33,41 showing that some patients were too disturbed by the topic to proceed with ACP.33 One patient reported feeling better and was, therefore, reluctant to follow-up the end-of-life conversation.29

Synthesis of results

Three different, but closely related, main themes were identified which reflected the experiences of patients with ACP conversations namely: ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’. Themes, subordinated themes and subthemes, are presented in Table 5. ‘Ambivalence’ was identified in 18 studies 28–34,41–43,45,47–53 and ‘readiness’ in 18 studies.28–34,42–48,50–53 The theme ‘openness’ was found in all studies.

Table 5.

Themes.

| Main theme | Subordinate theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|---|

| Ambivalence | ||

| Positive aspects | ||

| Receiving information | ||

| Being in control | ||

| Thinking about end of life | ||

| Learning | ||

| Confrontation | ||

| Unpleasant feelings | ||

| It’s not easy to talk about | ||

| Confrontation | ||

| Possible solution | ||

| Group session | ||

| Readiness | ||

| Being ready | ||

| Readiness is needed for ACP to be useful | ||

| Not being ready | ||

| Invitation | ||

| Resistance in advance | ||

| In hindsight pleased | ||

| Documentation | ||

| Timing of ACP | ||

| Assess readiness | ||

| Openness | ||

| Positive aspects | ||

| Relatives: Enables to become a surrogate decision-maker | ||

| Relatives: Actively engage family in the ACP process | ||

| Difficulties | ||

| Relatives: Feeling uncomfortable to be open | ||

| HCP: Feeling uncomfortable to be open | ||

| Overcoming difficulties | ||

| Attitude facilitator |

ACP: advance care planning; HCP: healthcare professional.

Ambivalence

Several studies reported the patients’ ambivalence when involved in ACP. From the invitation to participate in an ACP conversation to the completion of a written ACP document, patients simultaneously experienced positive as well as unpleasant feelings. Such ambivalence was identified as a key issue in five studies.34,43,47,49,53Irrespective of whether the illness was in advanced stage, patients reported ACP to be informative and helpful in the trajectory of their illness, while participation in ACP was also felt to be distressing and difficult.47,49,53 ‘It’s not easy to talk about these things at all, but … information is power’. 43 Thirteen studies showed that patients who participated in ACP were positive about participation or felt it was necessary for them to participate in ACP also described negative experiences. However, the nature of these was not specified further.28–33,41,42,45,48,50–52

Positive aspects

Looking at why patients experienced ACP as positive, studies mentioned the information patients received during the ACP conversation and the way it was provided.28,29,32,42,43,47,52,53Information that made patients feel empowered was clear, tailored towards the individual patient’s situation, and framed in such a way that patients felt it was delivered with compassion and with space for them to express accompanying feelings and emotions.28,45 Another positive aspect of ACP was that it provided patients a feeling of control. This was derived from their increased ability to make informed healthcare decisions28,32,47 and to undertake personal planning.28,32,42 Patients also mentioned that the ACP process offered them an opportunity to think about the end of their life. This helped them to learn more about themselves and their situation, such as what kind of care they would prefer in the future. In addition, participating in ACP made them feel respected and heard.32–34,41–43,48,49,51–53 One patient summarised it by saying that ACP allowed him to feel that ‘everything was in place’.34

Unpleasant feelings

Turning to the unpleasant feelings evoked during the process of ACP, these were often caused by the difficulty to talk about ACP, especially because of the confrontation with the end of life. Patients particularly experienced this confrontation at the moment of invitation and during the ACP conversation. Eleven studies,29,31,33,34,43,45,47,49–51,53 of which eight concerned an ACP intervention in a research context,33,34,43,47,49,50,51,53 reported that being invited and involved in ACP made patients realise that they were close to the end of their lives and this had forced them to face their imminent death.29,31,33,34,43,45,47,49,50,51,53 Four of these studies found that this resulted in patients feeling disrupted.31,33,50,53 In particular, an increased awareness of the seriousness of their illness and that the end-of-life could really occur to them, was distressing.31,33,50,53 A notable finding was that some patients in five studies,34,43,47,52,53 labelled the confrontation with their end-of-life as positive because it had helped them to cope with their progressive illness.

Possible solution

In order to overcome, or to soften, the confrontation with their approaching death, some patients offered the solution of a more general preparation. These patients had received general information on ACP through participation in a group ACP session with trained facilitators.30,50 They believed that the introduction of ACP in a more general group approach or by presenting it more as routine information was less directly linked with the message that they themselves had a life-threatening disease.30,50 In addition, patients who participated in a group setting mentioned that questions from other patients had been helpful to them.30 Particularly, those that they had not thought of themselves but of which the answers proved to be useful.30

Readiness

During our analysis we noticed how influential the patients’ ability and willingness to face the life-threatening character of the disease and to think about future care was during this process. Patients, both in earlier and advanced stages of their disease, refer to this as their readiness to participate in an ACP conversation.28,29,42,43,45,48,50,51,53

Being ready

One study involving seriously ill patients looked at their preferences regarding the behaviour of the physician during end-of-life communication.28 In response to their own ACP experience, several patients in this study suggested that an ACP conversation is only useful and beneficial when patients are ready for it.28

Not being ready

Of the patients in the studies which addressed ‘readiness’, some had not yet felt ready to discuss end-of-life topics at the moment they were invited for an ACP conversation.29,31,42,43,45,50–53 This was true both for an ACP intervention in a research context or an ACP conversation in daily practice, irrespective of the stage of illness. These patients reported either an initial shock when first being invited 31,50,51 or their initial resistance to participate in an ACP conversation.29,43,45,51–53 This was particularly true because of them being confronted with the life-threatening nature of their disease.29,31,33,42,45,50–53 In addition, some patients were worried about the possible relationship between the process of ACP and their forthcoming death.29,31,42,45,53 The patients in one study reported that introducing ACP at the wrong moment could both harm the patient’s well-being and the relationship between the patient and the HCP.28

In spite of the initial resistance of some patients to participate in an ACP conversation, most patients completed the conversation and in hindsight felt pleased about it.42,43,50–53 In two studies, a few patients felt too distressed by the topic and, as a consequence, had not continued the ACP conversation.29,33

Documentation

In nine studies, patients’ experiences in writing down their values and choices for future medical care were reported.32–34,44–46,51–53 Patients who participated in an ACP conversation and did not write a document about their wishes and preferences did not do so because they felt uncomfortable about completing such a document.45,51,53 This was particularly due to their sense of not feeling ready to do so.45,51,53 In addition, they mentioned their difficulty with planning their care ahead and their need for more information. Some patients felt reluctant to complete a document about their wishes and preferences due to their uncertainty about the stability of their end-of-life preferences in combination with their fear of no longer having an opportunity to change these.31,45,51,53 However, the patients who completed a document indicated it as a helpful way to organise their thoughts and experienced it as a means of protecting their autonomy.32–34,44–46,51,52 In a study about the experiences of ALS patients with a living will, a few said that they had waited until they felt ready to complete their living will. This occurred when they had accepted the hopelessness of the disease or when they experienced increasingly severe symptoms.45

Timing of ACP

In addition, in three studies investigating patients’ experiences with an ACP intervention in a research context, patients emphasised that an ACP conversation should take place sooner rather than later.42,47,51 In a study among cancer patients about a video intervention as part of ACP, patients mentioned that ‘It is better to deal with these things when you are reasonably healthy’.47 In two studies, patients suggested that it would be desirable to assess the patient’s readiness for an ACP conversation by just asking patients how much information they would like to receive.28,48

Openness

In all included studies, it appeared that besides sharing information with their HCP or the facilitator who conducted the ACP conversation, patients were also stimulated to share personal information and thoughts with relatives, friends or informal carers.28–34,41–53 ‘Openness’ in the context of ACP refers to the degree to which patients are willing to or feel comfortable about sharing their health status and personal information, including their values and preferences for future care, with relevant others.

Positive aspects

Some patients, including a number who were not yet in an advanced stage of the illness, positively valued being open towards the HCP about their options and wishes. An open dialogue enabled them to ask questions related to ACP and to plan for both current and future medical care.28,29,32,44,45,47,51 Openness towards relatives was also labelled as positive by many patients.28,30,33,34,42–44,46,48,49,52,53 Patients appreciated the relatives’ awareness of their wishes and preferences, which enabled them to adopt the role of surrogate decision-maker in future, should the patient become too ill to do so his or herself.28,30,33,34,42–44,46,48,49,52,53 Most patients thought their openness would reduce the burden on their loved ones.28,33,34,46,47,49,51,52 In two studies, patients described a discussion with family members that led to the completion of the patients’ living wills.45,53 Because of these positive aspects of involving a relative in the ACP process, some patients emphasised that the facilitator should encourage patients to involve relatives in the ACP process and to discuss their preferences and wishes openly.28,43

Difficulties

On the other hand, openness did not always occur. Eight studies reported patients’ difficulties being open about their wishes and preferences towards others.32,33,41,43–45,49,53 Some patients had felt uncomfortable about discussing ACP with their HCP because they considered their wishes and preferences to be personal.32,33,49 Others felt that an ACP conversation concerned refusing treatment and, as such, was in conflict with the work of a doctor.43,45

The difficulties reported about involving relatives derived from patients’ discomfort in being open about their thoughts.32,33,44,53 Some patients consciously decided not to share these. For instance, patients felt that the family would not listen or did not want to cause them upset.32,33,43,44 The ACP conversation did occasionally expose family tensions such as feelings of being disrespected or about the conflicting views and wishes of those involved.41,53

Overcoming difficulties

According to the patients, the facilitator who conducted the ACP conversation had the opportunity to support patients to overcome some of these difficulties.28,30,32,48,52 Patients highlighted that when the facilitator showed a degree of informality towards the patient during the conversation, was supportive and sensitive – which in this context meant addressing difficult issues without ‘going too far’ – they felt comfortable and respected.28,30,32,48 This enabled them to be open about their wishes and thoughts.28,30,32,48

Discussion

Main findings

This systematic review of research findings relating to the actual experiences with ACP of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness shows that ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’ play an important role in the willingness and ability to participate in ACP. Previous studies involving hypothetical scenarios for ACP indicate that it can have both positive and negative aspects for patients.9,11,13,19,20 This systematic review now takes this further showing that individual patients can experience these positive and unpleasant feelings simultaneously throughout the whole ACP process. However, aspects of the ACP conversation that initially are felt to be unpleasant can later be evaluated as helpful. Albeit that patients need to feel some readiness to start with ACP, this systematic review shows that the ACP process itself can have a positive influence upon the patient’s readiness. Finally, consistent with the literature concerning perceptions of ACP,9,11,13,19,20 sharing thoughts with other people of significance to the patient was found to be helpful. However, this systematic review reveals that openness is also challenging and patients need to feel comfortable in order to be open when discussing their goals and plans for future care with those around them.

What this study adds

All three identified themes hold challenges for patients during the ACP process. Patients can appraise these challenges as unpleasant and this might evoke distress.56–58 For example, the confrontation with being seriously ill and/or facing death, which comes along with the invitation and participation in an ACP conversation, can be a major source of stress. In addition, stress factors such as sharing personal information and wishes with significant others or, fearing the consequences of written documents which they feel they may not be able to change at a later date, may also occur later in the ACP process. All these stress factors pose challenges to coping throughout the ACP process.

The fact that the process of ACP in itself may help patients to discuss end-of-life issues more readily, might be related to aspects of the ACP process which patients experience as being meaningful to their specific situation. It is known from the literature on coping with stress that situational meaning influences appraisal, thereby diminishing the distress.58 Participation in the ACP process suggests that several perceived stress factors can be overcome by the patient. Although ACP probably does not take away the stress of death and dying, participation in ACP, as our results show, may bring patients new insights, a feeling of control, a comforting or trusting relationship with a relative or other experiences that are meaningful to them.

Patients use a variety of coping strategies to respond to their life-threatening or life-limiting illness and, since coping is a highly dynamic and individual process, the degree to which patients’ cope with stress can fluctuate during their illness.59–61

ACP takes place within this context. Whereas from the patients’ perspective ACP may be helpful, HCPs should take each individual patients’ barriers and coping styles into account to help them pass through the difficult aspects of ACP in order to experience ACP as meaningful and helpful to their individual situation.

The findings of this systematic review suggest that the uptake and experience of ACP may be improved through the adoption of a personalised approach, reflectively tailored to the individual patient’s needs, concerns and coping strategies.

While it is widely considered to be desirable that all patients approaching the end of life should be offered the opportunity to engage in the process of ACP, a strong theme of this systematic review is the need for ‘readiness’ and the variability both in personal responses to ACP and the point in each personal trajectory that patients may be receptive to such an offer. Judging patients’ readiness’, as a regular part of care, is clearly a key skill for HCPs to cultivate in successfully engaging patients in ACP. An aspect of judging patients’ ‘readiness’ is being sensitive to patients’ oscillation between being receptive to ACP and then wishing to block this out. Some patients may never wish to confront their imminent mortality. However, it is evident that ACP may be of great value, even for patients who were initially reluctant to engage, or who found the experience distressing. Therefore, HCPs could provide information about the value of participation in ACP, given the patient’s individual situation.

If patients remain unaware of ACP, they are denied the opportunity to benefit. Consequently, it is important that information about the various ACP options should be readily available in a variety of formats in each local setting. Given the challenges of ACP and the patient’s need to feel comfortable in sharing and discussing their preferences, HCPs should be sensitive and willing to openly discuss the difficulties involved.

Several additional strategies can be helpful. First, ACP interventions can include a variety of activities, for example, choosing a surrogate decision-maker, having the opportunity to reflect on goals, values and beliefs or to document one’s wishes. Separate aspects can be more or less relevant for patients at different times. Therefore, HCPs could monitor patients’ willingness to participate in ACP throughout their illness, before starting a conversation about ACP or discussing any aspect of it. Second, the option of participating in a group ACP intervention could be a helpful means of introducing the topic in a more ‘hypothetical’ and non-threatening way, especially for patients who are reluctant to participate in an individual ACP conversation. An initial group discussion could lower the barriers to subsequently introducing and discussing personal ACP with the HCP.30,50

The reality remains that discussing ACP with patients requires initiative and effort from HCPs. Even skilled staff in specialist palliative care roles experience reluctance to broach the topic and difficulty in judging how and when to do so.29,62,63 Therefore, it is important that HCPs are provided with adequate knowledge and training about all aspects of ACP (e.g. appointment of proxy decision-makers as well as techniques for sensitive discussion of difficult topics). It may be helpful for HCPs to have access to different practical tools or ACP interventions which they can use in the care of patients during their end-of-life trajectory. For example, an interview guide with questions that have been established to be helpful could offer guidance to HCPs when asking potentially difficult questions. For that reason, it is important for future research to study the benefits of (different aspects of) ACP interventions in order to improve the care and decision-making processes of patients with a life-threatening or life-limiting illness.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this systematic review should be taken into account. First, the articles included were research studies offering an ACP intervention in a research context or studies evaluating daily practice with ACP. It is likely that the patients included here were self-selected for participation in these studies because they felt ready to discuss ACP. This would represent a selection bias, influencing patients’ experiences with ACP positively. However, from the studies that reported patients’ refusals to participate, we learnt that part of the patients felt initial resistance to ACP and a small number of patients refused participation because they felt not ready. Second, our search was limited to articles published in English.

Conclusion

This systematic review of the evidence of patients’ experiences of ACP showed that patients’ ‘ambivalence’, ‘readiness’ and ‘openness’ play an important role in their willingness and ability of patients to participate in an ACP conversation. We recommend the development of a more personalised ACP, an approach which is reflectively tailored to the individual patient’s needs, concerns and coping strategies. Future research should provide insights into the potential for ACP interventions in order to benefit the patient’s experience of end-of-life care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lotty Hooft and René Spijker for their insight and expertise in literature searches that greatly assisted this systematic review. They thank René Spijker also for performing the literature search. M.Z. has contributed to the design of the work, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. L.J.J. and M.C.K. have contributed to the design of the work, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. J.J.M.V.D., A.V.D.H., I.J.K., K.P., J.A.C.R. and J.S. have contributed to the design of the work, analysed and interpreted data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: M Zwakman  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2934-8740

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2934-8740

JAC Rietjens  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0538-5603

References

- 1. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, Van Der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014; 28(8): 1000–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academy of Medicine (NAM). Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Hospice Palliative Care Organization. Advance Care planning, 2016, https://www.nhpco.org/advance-care-planning

- 5. Teno JM, Nelson HL, Lynn J. Advance care planning. Priorities for ethical and empirical research. Hastings Cent Rep 1994; 24(6): S32–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, et al. Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58(7): 1233–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53(2): 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: the patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1(5): 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seymour J, Almack K, Kennedy S. Implementing advance care planning: a qualitative study of community nurses’ views and experiences. BMC Palliat Care 2010; 9: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(9): 1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Musa I, Seymour J, Narayanasamy MJ, et al. A survey of older peoples’ attitudes towards advance care planning. Age Ageing 2015; 44(3): 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mullick A, Martin J, Sallnow L. An introduction to advance care planning in practice. BMJ 2013; 347: f6064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. A call for high-quality advance care planning in outpatients with severe COPD or chronic heart failure. Chest 2011; 139(5): 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horne G, Seymour J, Payne S. Maintaining integrity in the face of death: a grounded theory to explain the perspectives of people affected by lung cancer about the expression of wishes for end of life care. Int J Nurs Stud 2012; 49(6): 718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barakat A, Barnes SA, Casanova MA, et al. Advance care planning knowledge and documentation in a hospitalized cancer population. Proc 2013; 26(4): 368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(1): 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jabbarian LJ, Zwakman M, van der Heide A, et al. Advance care planning for patients with chronic respiratory diseases: a systematic review of preferences and practices. Thorax 2018; 73(3): 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scott IA, Mitchell GK, Reymond EJ, et al. Difficult but necessary conversations–the case for advance care planning. Med J Aust 2013; 199(10): 662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simon J, Porterfield P, Bouchal SR, et al. ‘Not yet’ and ‘Just ask’: barriers and facilitators to advance care planning – a qualitative descriptive study of the perspectives of seriously ill, older patients and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(1): 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson S, Butow P, Kerridge I, et al. Advance care planning for cancer patients: a systematic review of perceptions and experiences of patients, families, and healthcare providers. Psychooncology 2016; 25(4): 362–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimbell B, Murray SA, Macpherson S, et al. Embracing inherent uncertainty in advanced illness. BMJ 2016; 354: i3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(9): e543–e551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 22–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papaioannou D, Sutton A, Carroll C, et al. Literature searching for social science systematic reviews: consideration of a range of search techniques. Health Info Libr J 2010; 27(2): 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Booth A, Papaioannou D, Sutton A. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review.1st ed. London, United Kingdom: SAGE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schlosser RW Wendt O Bhavnani S et al.. Use of information-seeking strategies for developing systematic reviews and engaging in evidence-based practice: the application of traditional and comprehensive pearl growing. A review. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2006; 41(5): 567–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abdul-Razzak A, You J, Sherifali D, et al. ‘Conditional candour’ and ‘knowing me’: an interpretive description study on patient preferences for physician behaviours during end-of-life communication. BMJ Open 2014; 4(10): e005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Almack K, Cox K, Moghaddam N, et al. After you: conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliative Care 2012; 11: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burge AT. Advance care planning education in pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study exploring participant perspectives. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 1069–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacPherson A, Walshe C, O’Donnell V, et al. The views of patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on advance care planning: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horne G, Seymour J, Shepherd K. Advance care planning for patients with inoperable lung cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12(4): 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singer PA, Martin DK, Lavery JV, et al. Reconceptualizing advance care planning from the patient’s perspective. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martin DK, Thiel EC, Singer PA. A new model of advance care planning: observations from people with HIV. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chambers L Dodd W McCulloch R et al.. A guide to the development of children’s palliative care services. 3rd ed. ACT; 2009. Report No.: ISBN 1 898 447 09 8. Bristol, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greater Manchester Eastern Cheshire Strategic Clinical Networks. Life limiting ilness, 2015, http://www.gmecscn.nhs.uk/index.php/networks/palliative-and-end-of-life-care/information-for-patients-carers-and-families/life-limiting-illness (accessed 02 February 2018)

- 37. Covidence. Covidence, 2015, www.covidence.org

- 38. CASP UK. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: CASP Qualitative Research Checklist, 2017, http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf (accessed February 2018)

- 39. Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance paper 2: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. Epub ahead of print 2 January 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Andreassen P, Neergaard MA, Brogaard T, et al. The diverse impact of advance care planning: a long-term follow-up study on patients’ and relatives’ experiences. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bakitas M, Dionne-Odom JN, Jackson L, et al. ‘There were more decisions and more options than just yes or no’: evaluating a decision aid for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2016; 12: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnes KA, Barlow CA, Harrington J, et al. Advance care planning discussions in advanced cancer: analysis of dialogues between patients and care planning mediators. Palliat Support Care 2011; 9: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brown M, Brooksbank MA, Burgess TA, et al. The experience of patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and advance care-planning: a South Australian perspective. J Law Med 2012; 20(2): 400–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burchardi N, Rauprich O, Hecht M, et al. Discussing living wills. A qualitative study of a German sample of neurologists and ALS patients. J Neurol Sci 2005; 237(1–2): 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen H, Habermann B. Ready or not: planning for health declines in couples with advanced multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2013; 45(1): 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, et al. ‘We have to discuss it’: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psychooncology 2015; 24(12): 1767–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Metzger M, Song MK, Devane-Johnson S. LVAD patients’ and surrogates’ perspectives on SPIRIT-HF: an advance care planning discussion. Heart Lung 2016; 45(4): 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robinson CA. Advance care planning: re-visioning our ethical approach. Can J Nurs Res 2011; 43(2): 18–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sanders C, Rogers A, Gately C, et al. Planning for end of life care within lay-led chronic illness self-management training: the significance of ‘death awareness’ and biographical context in participant accounts. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66(4): 982–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Simon J, Murray A, Raffin S. Facilitated advance care planning: what is the patient experience? J Palliat Care 2008; 24(4): 256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Simpson CA. An opportunity to care? Preliminary insights from a qualitative study on advance care planning in advanced COPD. Prog Palliate Care 2011; 9(5): 243. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Michael N, O’Callaghan C, Baird A, et al. A mixed method feasibility study of a patient- and family-centred advance care planning intervention for cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006; 6: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007; 12(1): 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45(8): 1207–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985; 48(1): 150–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Rev Gen Psychol 1997; 1(2): 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Copp G, Field D. Open awareness and dying: the use of denial and acceptance as coping strategies by hospice patients 2002; 7(2): 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morse JM, Penrod J. Linking concepts of enduring, uncertainty, suffering, and hope. Image J Nurs Sch 1999; 31(2): 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999; 23(3): 197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Parry R, Land V, Seymour J. How to communicate with patients about future illness progression and end of life: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4(4): 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pollock K, Wilson E. Care and communication between health professionals and patients affected by severe or chronic illness in community care settings: a qualitative study of care at the end of life. Health Serv Deliv Res 2015; 3: 31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]