Abstract

The Healthy People 2020 (HP2020) Midcourse Review (MCR) presents an opportunity for professionals in the disability and health field to contemplate preliminary progress toward achieving specific health objectives. The MCR showed notable progress in access to primary care, appropriate services for complex conditions associated with disability, expansion of health promotion programs focusing on disability, improving mental health, and reducing the unemployment rate among job seekers with disabilities. This commentary presents potential considerations, at least in part, for such progress including increased access to health care, greater awareness of appropriate services for complex conditions, and opportunities for societal participation. Additional considerations are provided to address the lack of progress in employment among this population – a somewhat different measure than that for unemployment. Continuing to monitor these objectives will help inform programs, policies, and practices that promote the health of people with disabilities as measured by HP2020.

Keywords: Disability, Healthy People, Midcourse Review

Health is an important concern for all population groups including people with disabilities who experience health disparities in comparison with the general population. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) first began reporting on the nation's health in 1979 through Healthy People,1 wherein it was noted that due to public health improvements related to communicable diseases, “Americans are healthier today than we have ever been.” With communicable disease rates falling and knowledge growing about chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, programs began to focus intently on disease prevention.2 These prominent health threats, evolving within a changing social milieu, formed the basis for developing a formal strategic plan to address them.

Beginning in 1980,3 overseen by HHS and renewed every decade, the first strategic plan was developed which later evolved as a decennial strategic resource for coordinating and promoting national health. The first strategic plan did not specifically address people with disabilities –defined as those with functional limitations caused by physical, sensory, cognitive or mental impairments.4 However, agenda-setting initiatives such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (PL 101–336, 104 Stat. 328 (1990), https://www.ada.gov/2010_regs.htm) and the Disability in America5 report increasingly highlighted the importance of integrating people with disabilities into national population-based efforts to improve the public's health. To facilitate this integration, HHS commissioned a task force to review the 1990 objectives.6

Based on this review, 20 measures relating to people with disabilities were added in the Healthy People 2000 (HP2000) plan. Spread across various chapters, these measures addressed improving lifestyle issues (e.g., weight management); mental health treatment; community-based services; patient education for those with chronic conditions; prevention of disabilities (e.g., trauma and early newborn screening); functioning among older adults and people with asthma; and worksite hiring policies. The 1997 HP2000 Progress Review highlighted health improvements among people with disabilities, i.e., reduced sedentary behavior; increased use of community-based support programs for those with mental disorders; and increased receipt of recommended clinical preventive services.7 These improvements stimulated the development of a single chapter focused on people with disabilities in the next iteration of Healthy People.8

In Healthy People 2010 (HP2010), a new chapter entitled Disability and Secondary Conditions was added. While developing a HP2010 chapter focused on people with disabilities was a significant advance, many constraints existed, including negotiating the addition of a standard set of questions to identify respondents with disabilities across various national surveys; coordinating with various federal disability programs and constituents; and clarifying health policies affecting people with disabilities. Nonetheless, HHS recognized the importance of addressing the health of people with disabilities and subsequently approved the addition of 13 new objectives represented by 21 measures. By the year 2010, improvements were seen in objectives related to increases in state health surveillance for people with disabilities and caregivers; reductions in adults living in large congregate care facilities; increases in children and youth with disabilities who attend regular school classrooms; and reductions in depression among children and adolescents with disabilities.9 In addition to the objectives in the new disability chapter, people with disabilities (referred to as having activity limitations) were represented as a demographic group in 207 out of 467 objectives in the HP2010 plan. Of those 207 objectives, 88 yielded data for people with disabilities, making Data20109 the single largest collection of published data for this population, a major milestone in the United States. By the close of 2010, there was a growing recognition of the extent of disparities in health status and outcomes among people with disabilities, compared to other demographic segments of society.10–12 Editors of the first edition of the Disability and Health Journal13 heralded this time frame as the “coming of age of a field,” suggesting that the country was entering a new era of increased collective understanding of disability and health within scientific communities, public health, and society.

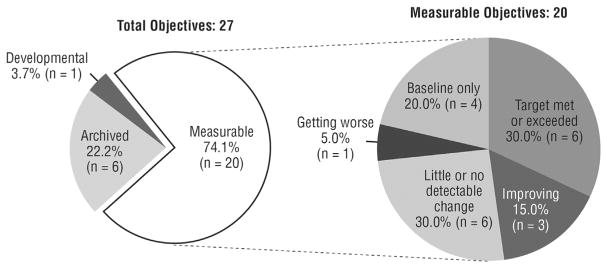

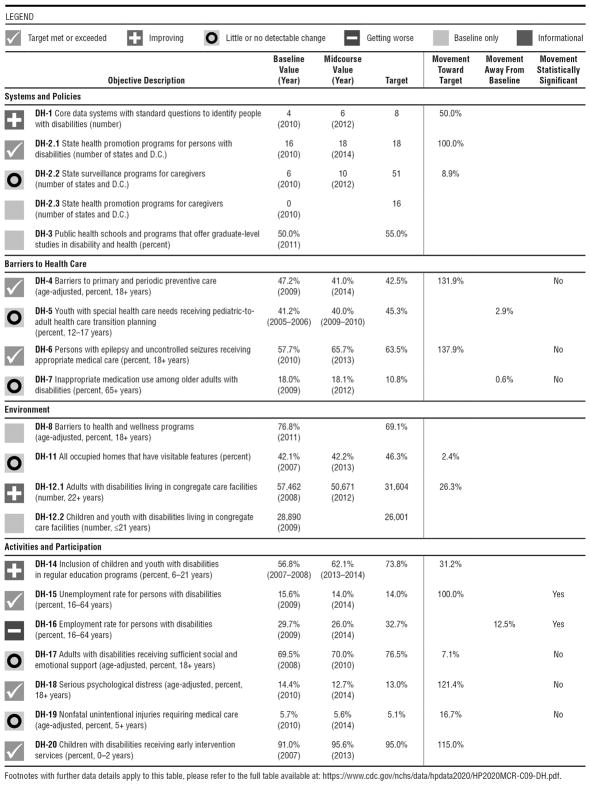

This new era highlighted the importance of improving health and addressing health disparities among people with disabilities; thus, in the next iteration, Healthy People 2020 (HP2020), the disability chapter was renamed Disability and Health. The original objectives in the HP2010 disability chapter were carried forward into HP2020 and seven were added, resulting in 27 objectives overall. The HP2020 planning process incorporated models of upstream and social determinants of health.14 Among such models, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health15 was used to organize the disability objectives under four broad areas: Systems and Policies; Barriers in Health Care; Environment; and Activities and Participation. Under those four broad areas, the status of each of the 27 objectives in the Disability and Health chapter was presented in a recently published HP2020 Midcourse Review (MCR).16 It is important to note that each objective uses data from a specific data source. The data details (survey methods and questions used to operationalize the objective) are available at https://www.healthypeople.gov/node/3501/data-details. Excerpted from the HP2020 MCR, Fig. 1 shows that of the 27 objectives, 20 were measurable, meaning at least baseline data were available. Of those that were measurable, six met or exceeded the target, three showed improvement, six showed little or no detectable change, and one showed regression. The other four only had baseline measurements available. Fig. 2 (also excerpted) provides more detail for each objective. One of the intentions of the MCR is to prompt further discussions about progress toward the objectives. This commentary provides a perspective on the disability and health objectives that have met or exceeded their 2020 targets and any that have moved away from their target. These objectives were selected as most likely to be influenced by recent or sustained health policies and practices. The perspectives that are presented are intended to inform ongoing efforts to achieve the other disability and health objectives.

Fig. 1.

HP2020 Midcourse Review: Overall status of the disability and health objectives.16

Fig. 2.

HP2020 Midcourse Review: Progress for measurable disability and health objectives.16

Discussion of selected objectives

This commentary is limited to a discussion of six HP2020 disability and health objectives for which the target has been met or exceeded and one objective that is moving away from the target. Objectives that met or exceeded their targets included DH-2.1 increasing state disability health promotion programs; DH-4 reducing barriers to primary care; DH-6 increasing appropriate care for epilepsy; DH-15 reducing unemployment; DH-18 reducing psychological distress; and DH-20 increasing early intervention services in community settings. The objective whose measurement moved away from its target is DH-16 increasing employment.

Meeting or exceeding the target

DH-2.1 health promotion programs aimed at improving the health and well-being of people with disabilities

A key role of health departments is to cooperate in building administrative infrastructure and implementing community-based programs to improve population health,17 including the health of people with disabilities. The MCR shows that the number of states with funding to implement health promotion programs for people with disabilities increased from 16 in 2010 to 18 in 2014, meeting the 2020 target. In 2016, a total of 19 state Disability and Health Promotion Programs were operational, surpassing the target of 18 states (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/programs.html). This expansion in state Disability and Health Promotion Programs coincided with advances in community-based health promotion practices supported through funding agencies such as the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities; the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research; and the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research. Each of these agencies has contributed to community-based practices, similar to Living Well with a Disability,18 and Health Matters.19 This cooperation among government agencies in developing health promotion interventions fosters their translation, in this case, by state Disability and Health Promotion Programs and their partners.

DH-4 barriers to primary care

The HP2020 MCR indicated that the percentage of adults with disabilities who reported delays in receiving primary care decreased from 47.2% in 2009 to 41.0% by the end of 2014, exceeding the 2020 target of 42.5%. Delays in primary care can be due to many things. The data source for this objective assesses delays in primary care related to six common barriers: getting through on the phone; getting an appointment; long wait times; office hours; transportation; and cost. As four of these barriers are office-based, progress toward objective DH-4 may be derived from efforts to reduce waiting room times20 and increase access to clinical services using online platforms.21 Additional efforts to improve physical access (e.g., parking, transportation, etc.)22,23; and reduce unemployment (see DH-15 below) to mitigate out-of-pocket costs, may have also contributed to progress for this objective.

DH-6 medical care for epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures

As shown in the HP2020 MCR, the percentage of adults with epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures who received appropriate medical care rose from 57.7% in 2010 to 65.7% in 2013, exceeding the 2020 target of 63.5%. Improvement may be linked to efforts to standardize epilepsy surveillance,24 raise awareness of epilepsy through social media, and increase patients' awareness of how to find appropriate care through a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy (https://www.epilepsy.com/living-epilepsy/find-epilepsy-specialist). In addition to focusing on patients, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the National Institutes of Health; and their grantees and partners have worked to increase awareness among providers about the need for specialty care for uncontrolled seizures. These combined efforts have likely positively influenced this objective.

DH-15 unemployment

The HP2020 MCR indicated a drop in unemployment among people with disabilities (ages 16–64 years) who were looking for jobs but not getting hired. Unemployment decreased from 15.6% in 2009 to 14% in 2014, thus meeting the HP2020 target of 14%. Beyond the MCR, DATA2020 suggests continued progress, with an estimate of 11.7% in 2015 (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search). In a separate report, unemployment also improved among people without disabilities (ages 16 and older) from 9.0% in 2009 to 5.1% in 2015 (https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2017/unemployment-rate-of-people-with-a-disability-10-point-5-percent-in-2016.htm?view_full). This objective has been advanced through efforts to promote hiring practices and assist people with disabilities who want to participate in the workforce, whether in the public or private sector. Between 2011 and 2015, 109,575 part-time and full-time federal career employees with disabilities were hired, representing 14.4% of the overall federal workforce.25 In addition, tax subsidies gave businesses further incentives to hire people with disabilities,26 while some businesses were already demonstrating their commitment to hire people with disabilities. For example, near the beginning of the decade, Walgreens set a goal to hire people with disabilities in 10% of their cashier and other retail positions27; and Proctor & Gamble aimed to hire people with physical and developmental disabilities in 30% of their packaging positions in Maine.28 In addition, many other leading companies have been recognized for having sound hiring and retention practices regarding workers with disabilities, e.g., Prudential Financial, Delta, International Business Machines, Merke & Co Inc., Sprint, AT&T, Kaiser Permanente, and Comcast NBC Universal, to name a few.29 Unemployment rates reflect the employment status of those actively looking for work (an individual choice and perception of opportunity), which represents a smaller proportion of the disability population than that assessed in the employment measure (see DH-16 below).

DH-18 serious psychological distress

The overall prevalence of serious psychological distress (SPD) among adults with disabilities dipped from 14.4% in 2010 to 12.7% in 2014, exceeding the HP2020 target of 13%. Although the aggregate data appear encouraging, the 2014 dip in SPD does not reflect the nuances in the data (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search). Progress varied substantially by sex, race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status. For example, in the period 2010 to 2014, SPD increased among men from 11.9% to 13.3% but decreased among women from 16.7% to 12.0%. SPD decreased among non-Hispanic Whites from 15.1% to 11.5% and among non-Hispanic Blacks from 12.2% to 8.7%, but increased among Hispanics from 15.6% to 18.2%. Across those years, SPD was more prevalent among those with the lowest family income (<100% of the poverty threshold) and the lowest educational attainment (less than high school). While SPD was found in all categories of all sociodemographic groups, it consistently correlates with socioeconomic status, and other social determinants.30–32 Many socioecological circumstances contribute to SPD, which in turn can affect one's overall health making SPD an important health measure to continue monitoring.

DH-20 early intervention services in community-based settings

This objective highlights the importance of identifying children who need services as early as possible and delivering those services in the most natural and least disruptive setting for them. The HP2020 MCR shows that the percentage of children with disabilities from birth through 2 years (also called birth to 3) who received early intervention services in home or community-based settings rose from 91.0% in 2007 to 95.6% in 2013, exceeding the Healthy People target of 95%. Initially put in place through Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (PL 108–446, 118 Stat. 2647 (2004), https://www.copyright.gov/legislation/pl108-446.pdf), the availability and delivery of early intervention services in community-based settings continues to rise with more attention on gaps, such as finding infants who are eligible.33 Contributing to this steady rise is a large number of young children who are identified early through programs, such as the Early Hearing and Detection Intervention (EHDI) newborn screening program.34 In addition, successful programs, such as Learn the Signs, Act Early©,35 have increased parents' and health care providers' awareness of the importance of early screening and interventions.

Moving away from the target

DH-16 employment

As demonstrated in the HP2020 MCR, the employment rate is different than the unemployment rate. The employment rate, also known as the employment-to-population ratio, reflects the proportion of working-age individuals who are employed among the total number of working-age individuals. Among working-age people without disabilities (ages 16–64 years), employment rose from 70.7% in 2009 to 71.7% in 2014,36 suggesting a slow recovery from the economic recession that began in 2007.37 Among working-age people with disabilities (ages 16–64 years), employment fell from 29.7% in 2009 to 26% in 2014, suggesting no recovery for this population and moving away from the Healthy People target of 32.7%. Beyond the MCR, DATA2020 (https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search) suggests some recovery for those with disabilities from 26% in 2014 to 26.9% in 2015. This is consistent with another report that suggests improvements in employment among people with disabilities during 2015 and 2016.38 The School to Employment Program (STEP) (http://transitionschooltowork.org); workplace accommodation strategies (https://www.washington.edu/doit/strategies-working-people-who-have-disabilities); and changes in health insurance programs39 are examples of actions that can influence employment among people with disabilities.

Summary

As a half-way point, the HP2020 MCR showed encouraging progress toward improving some health and health-related outcomes for people with disabilities. Several program efforts have likely contributed to the overall progress seen in the Disability and Health Chapter. Such efforts include improving public awareness and appropriate treatment for serious conditions (e.g., uncontrolled seizures and early developmental delays); and support for health promotion programs intended to improve the quality of life and health of people with disabilities. Efforts to reduce delays in primary care due to barriers are both broad as well as specific to people with disabilities, and the connections between health and employment appear interdependent with health allowing greater opportunities to seek and gain employment, and employment allowing greater access to health care. Though the HP2020 MCR, did not confirm concurrent progress in both unemployment and employment, data beyond the MCR appear promising and monitoring each objective will continue through 2020.

The HP2020 MCR highlights the nation's health and progress towards the 10-year national health goals and objectives set forth in 42 chapters, including Disability and Health.16 The HP2020 MCR offers an opportunity to reflect on this decade's progress towards improving the health and quality of life for people with disabilities living in this country as well as possible factors affecting the health of people with disabilities in coming years. Remaining challenges are sustaining and achieving additional progress in the Disability and Health Chapter, as well as examining and discussing progress for other objectives, within other chapters, where people with disabilities are identified as a demographic group (see figure III-4 in the HP2020 MCR).

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors have not made prior presentations or abstracts at meetings of any part of the material presented in this manuscript. There were no sources of funding (direct or indirect) for authors in regards to this report.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Institutes of Health. The authors have no competing interests.

The authors would like to thank Barbara Disckind (Office on Women's Health, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, and Healthy People 2020 Disability and Health Workgroup member) for careful her review and edits; Robin Pendley (National Center for Health Statistics and Healthy People 2020 Disability and Health Workgroup member) for her data review and comment; and Kyung Park (National Center for Health Statistics) for her graphics support.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.U.S. Public Health Service. Healthy People: The Surgeon General's Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1979. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. [Publication no. 79–55071] https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/G/K/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fifty years of progress in chronic disease epidemiology and control. MMWR Suppl. 2011;60(4):70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health. Education and Welfare. Promoting Health, Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brault MW. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2012. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. Americans with Disabilities: 2010; pp. P70–131. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2012/demo/p70-131.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nova Research Company. Analysis of the 1990 Health Objectives for the Nation for Applicability to Prevention of Disabilities. Report for the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bethesda, MD: Nova Research Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2000 Review, 1997. Hyattsville, Maryland: Public Health Service; 1997. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 76–641496 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hp2000/hp2k97.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGinnis JM, Rothstein D. Preventing disabling conditions, the role of the private sector. In: Marge M, editor. Proceedings and Recommendations of the National Conference. Healthy People 2000 and Disability Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics. Data2010 [online database] Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed 7 December 2017]. https://wonder.cdc.gov/data2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havercamp S, Scandlin D, Roth M. Health disparities among adults with developmental disabilities, adults with other disabilities, and adults not reporting disability in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(4):418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krahn GL, Hammond L, Turner A. A cascade of disparities: health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12(1):70–82. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jette A, Field M. The Future of Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turk MA, McDermott S. From the editors. Disabil Health J. 2008;1(1):3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh HK. A 2020 vision for health people. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1653–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1001601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning. Geneva, Switzerland: Disability and Health (ICF); 2001. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2020 Midcourse Review. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020/hp2020_midcourse_review.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.William Mitchell College of Law. State & Local Public Health: An Overview of Regulatory Authority [Brief] Saint Paul, MN: Public Health Law Center; Apr, 2015. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. http://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/phlc-fs-state-local-reg-authority-publichealth-2015_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravesloot C, Seekins T, Traci M, et al. Living well with a disability: a self-management program. MMWR Suppl. 2016;65(1):61–67. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6501a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks B, Sisirak J, Heller T. Health Matters: Exercise and Nutrition Health Education Curriculum for Adults with Developmental Disabilities. Philadelphia, PA: Brookes Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michael M, Schaffer SD, Egan PL, Little BB, Pritchard PS. Improving wait times and patient satisfaction in primary care. J Healthc Qual. 2013;35(2):50–60. doi: 10.1111/jhq.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palen TE, Ross C, Powers JD, Xu S. Association of online patient access to clinicians and medical records with use of clinical services. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2012–2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamin G, Mitra M, Graham C, et al. CDC Grand Rounds: public health practices to include persons with disabilities. MMWR Wkly Rep. 2013;62(34):697–701. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight KE. Federally qualified health centers minimize the impact of loss of frequency and independence of movement of older adult patients through access to transportation services. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:1–6. doi: 10.4061/2011/898672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh HK, Kobau R, Whittemore VH, et al. Toward an integrated public health approach for epilepsy in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E146. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Report on the Employment of Individuals with Disabilities in the Federal Executive Branch. Washington, DC: Oct, 2016. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/diversity-and-inclusion/reports/disability-report-fy2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Internal Revenue Service. Tax Benefits for Businesses with Employees Who Have Disabilities. Washington, DC: Sep, 2017. [Accessed December 7, 2017]. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/tax-benefits-for-businesses-who-have-employees-with-disabilities. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diament M. Walgreens Bets Big on Employees with Disabilities. [Accessed December 7, 2017];Disability Scoop. 2012 Mar; https://www.disabilityscoop.com/2012/03/12/walgreens-employees-disabilities/15164/

- 28.Associated Press. Procter & Gamble hiring people with disabilities at Auburn plant. [Accessed December 7, 2017];Bang Dly News. 2011 Aug; http://bangordailynews.com/2011/08/02/business/proctor-gamble-hiring-people-with-disabilities-at-auburn-plant/

- 29.DiversityInc. [Accessed 7 December 2017];The DiversityInc Top 10 Companies for Hiring People with Disabilities. https://www.diversityinc.com/top-10-companies-people-with-disabilities/

- 30.Caron J, Liu A. Factors associated with psychological distress in the Canadian population: a comparison of low-income and non-low-income sub-groups. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(3):318–330. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myer L, Stein DJ, Grimsrud A. Social determinants of psychological distress in a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(8):1828–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phongsavan P, Chey T, Bauman A, Brooks R, Silove D. Social capital, socioeconomic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2546–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams RC, Tapia C The Council on Children with Disabilities. Early intervention, IDEA Part C services, and the medical home: collaboration for best practices and best outcomes. Pediatrics. 2014;132(4):e1073–e1088. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams TR, Alam S, Gaffney M. Progress in identifying infants with hearing lossd United States, 2006-2012. MMWR Wkly Rep. 2015;64(13):351–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Learn the Signs. [Accessed 7 December 2017];Act Early. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/

- 36.Lauer E. Current Population Survey (CPS) Analysis [unpublished] Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire, Institute on Disability; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dwyer GP, Lothian JR. [Accessed December 7, 2017];The Financial Crisis and Recovery: why so Slow? Notes from the Vault. 2011 Sep-Oct; https://www.frbatlanta.org/cenfis/publications/notesfromthevault/1110.aspx.

- 38.Curry AB. Special Edition: National Trends in Disability Employment. [Accessed December 7, 2017];Kessler National Employment Survey News. 2017 Jan; https://www.researchondisability.org/national-disability-employment-survey/kessler-natempsurv-news/2017/01/27/special-edition-national-trends-in-disability-employment-2016-review-2017-preview.

- 39.Hall JP, Shartzer A, Kurth NK, Thomas KC. Effect of Medicaid expansion on workforce participation for people with disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):262–264. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]