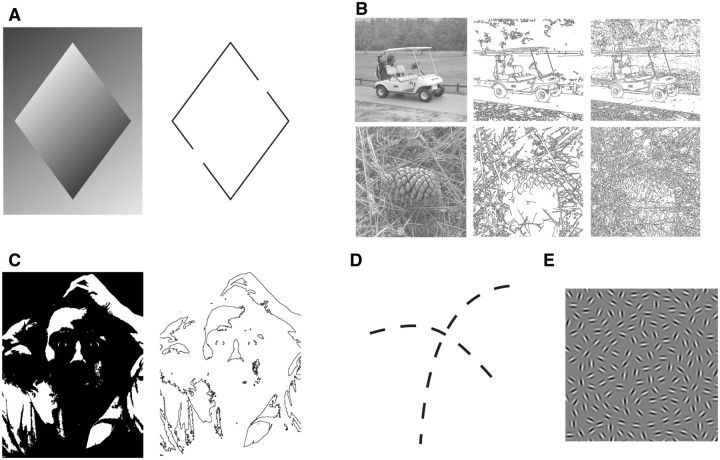

Figure 2.

Edge detection and boundary completion. (a) Some parts of the diamond are lighter than the background and other parts are darker than the background. As the dark to light (or light to dark) gradient is continuous, two points along the diamond’s edge match the luminance of the background. These points are indicated by the gaps in the line drawing to the right. Despite the absence of a discrete luminance edge at these locations, we perceive a continuous boundary around the arrow. This perceptual effect demonstrates that the visual system can perceptually complete discontinuous edges by assuming that they are part of the same boundary (boundary completion; image adapted from Wolfe J, Kluender K, Levi D et al. (2011). Sensation and Perception. Macmillan). (b) Grayscale photographs of a golf cart and a pinecone with the output of two popular edge-detection algorithms next to them (middle, Canny; right, Rothwel). Notice how each algorithm extracts edges in different parts of the image, and how many of these edges are disjointed to the point of complete obfuscation (Heath et al., 1997). (c) This two-tone image (left) becomes nearly unrecognizable when only luminance edges are shown (right; original image Le Désespéré by Gustave Courbet). (d) Discrete visual edges are perceptually grouped into two coherent contours even in the absence of clear surface boundaries. (e) Example of a stimulus where a subset of grating patches is aligned to create a circular micropattern. Stimuli such as these are used to study perceptual contour linking and boundary completion (reproduced from Mundhenk TN, Itti L. Computational modeling and exploration of contour integration for visual saliency. Biol Cybern 2005;93: 188–212, with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media).