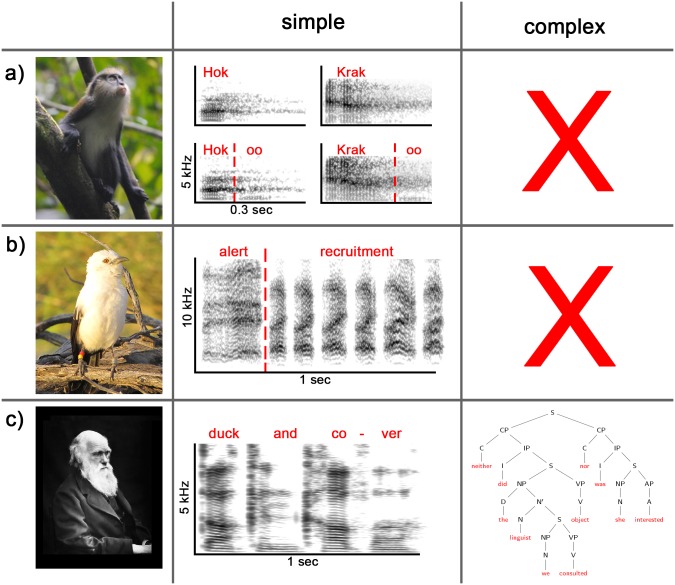

Fig 1. Simple and complex examples of compositionality in animals and humans.

a) Compositionality in primates: Male Campbell’s monkeys produce ‘krak’ alarms (to leopards) and ‘hok’ alarms (to eagles), but both calls can also be merged with an ‘-oo’ suffix to generate ‘krak-oo’ (to a range of disturbances) and ‘hok-oo’ (to non-ground disturbances) [55]. In playback experiments, suffixation has shown to be meaningful to listeners [5], suggesting that it is an evolved communication function. This system may qualify as limited compositionality, as the meanings of krak-oo and hok-oo are directly derived from the meanings of krak/hok plus the meaning of—oo [56]. Spectrograms regenerated using data from [55]. b) Compositionality in birds: Pied babblers produce ‘alert’ calls in response to unexpected but low-urgency threats and ‘recruitment’ calls when recruiting conspecifics to new foraging sites [6, 57]. When encountering a terrestrial threat that requires recruiting group members (in the form of mobbing), pied babblers combine the two calls into a larger structure, and playback experiments have indicated that receivers process the call combination compositionally by linking the meaning of the independent parts [6]. c) Compositionality in humans: humans are capable of producing both simple, nonhierarchical compositions (e.g., ‘Duck and cover!’) and complex hierarchical compositions and dependencies. Photo in panel A credited to Erin Kane. Photo in panel B credited to Sabrina Engesser. A, adjective; AP, adjective phrase; C, conjunction; CP, conjunction phrase; D, determiner; I, Inflection-bearing element; IP, inflectional phrase; N, (pro-)noun; NP, noun phrase; S, sentence; V, verb; VP, verb phrase.