Abstract

In this study, we document life stories of gay men who attempted suicide as adults. Our goal is to expand the collection of narratives used to understand this persistent health inequity. We interviewed seven adult gay men, each of whom had attempted suicide two to four times, and identified five narratives. Pride narratives resist any connection between sexuality and suicide. Trauma-and-stress narratives enable coping through acknowledgment of sexual stigma as a fundamental trauma and cause of subsequent stress and suicidal thoughts. Memorial narratives prevent suicide by maintaining a strong sense of “permanent” identity. Outing narratives demand that the listener confronts the legacy of unjust practices of homosexual surveillance and “outing,” which historically resulted in gay suicides. Finally, postgay narratives warn of the risk of suicide among older generations of gay men who feel erased from the goals of modern gay movements. Sexual identity concealment or invisibility featured prominently in all five narratives.

Keywords: gay, mental health, suicide, narrative research, qualitative, Canada

Creole began to tell us what the blues were all about. They were not about anything very new. He and his boys up there were keeping it new, at the risk of ruin, destruction, madness, and death, in order to find new ways to make us listen. For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn’t any other tale to tell, it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness. And this tale, according to that face, that body, those strong hands on those strings, has another aspect in every country, and a new depth in every generation. Listen, Creole seemed to be saying. Now these are Sonny’s blues.

—James Baldwin, Sonny’s Blues (1948, p. 139)

Introduction

A Scarcity of Contemporary Gay Suicide Narratives

Popular understandings of gay suicide have evolved over the course of the 20th century, through periods when homosexuality was regarded as a sin, illness, and crime—notions supported by prominent North American institutions, including those of the Christian churches, the State, medicine, and psychology (Rofes, 1983). Salient gay suicide narratives emerged in these contexts and became etched in the minds of heterosexuals and gays alike. Newspapers reproduced scandalous homosexual blackmail stories, which reinforced suicide as a presumed ending for those who otherwise risked public exposure as sexual deviants, while Hollywood films repeatedly employed a tragic, sensational gay suicide trope (Rofes, 1983; Russo, 1981).

Gay suicide is less clearly situated in the contemporary North American context, where homosexuality is no longer a crime and gay marriage now a legal reality. Familiar notions of gay suicide are, thus, largely relegated to bygone eras described above, as exemplified by the story of Alan Turing, re-popularized as a heroic tragedy in the 2014 Oscar-nominated film The Imitation Game. Turing was a mathematician credited with developing a modern computer to aid British espionage efforts during World War II. Turing also had sex with men and was, thus, branded as a security threat, and convicted under criminal code that outlawed sex between men. He was barred from continuing his government consultancy and forced to receive hormonal treatments to reduce his libido; in 1954, he died by poisoning himself with cyanide (Hodges, 2014).

To the extent that gay suicide is regarded as a contemporary social problem, it is characterized predominantly as a crisis of adolescence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). The story of Billy Lucas is illustrative. Lucas lived in Greensburg, Indiana, where he faced increasingly hostile bullying related to his perceived sexuality and, in the fall of 2010, died by hanging himself in his family’s barn (McKinley, 2010). His story is now remembered and credited—along with those of three other gay bullying-related teenage suicides that received widespread media attention in the fall of 2010—for launching It Gets Better, an Internet campaign that aims to persuade gay youth considering suicide to endure antigay stigma and hold out for a day when things will get better (Grzanka & Mann, 2014; McKinley, 2010).

These two stories are compelling in the direct and forceful ways in which they link antigay stigma to suicide; however, they also inherently limit the range of narratives used to understand gay suicide. Our collective “narrative resources” on the topic are rendered scarce (Frank, 2010). Turing’s story remains emotive but is given little credence in a postmarriage equality era. Meanwhile, Lucas’s story offers a contemporary “bullying-and-suicide” narrative but one that is particular to adolescence. We began the present research project by asking, “What stories are marginalized by dominant gay suicide narratives?” Our purpose is to expand our contemporary narrative resources with respect to gay suicide, by documenting the stories of gay men, alive today, who have attempted suicide as adults.

Opportunities in Qualitative Inquiry Into Gay Suicide

This project is fundamentally motivated by inequities in both rates of suicide attempts among gay, lesbian, bisexual (GLB) populations, and public health resources to prevent suicide in GLB communities (Hottes, Ferlatte, & Gesink, 2015). Even after decades of legal and political struggles to achieve equal status, nearly 20% of North American GLB adults surveyed between 1985 and 2008 attempted suicide; by comparison, the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in heterosexual populations is 4% (Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan, & Gesink, 2016). Statistical profiles of GLB suicide suggest an elevated rate of suicide attempts across the lifespan, contrary to the narrative featured in It Gets Better (Blosnich, Nasuti, Mays, & Cochran, 2016).

Epidemiological attempts to understand GLB suicide are limited. Deductive quantitative studies have frequently identified acute exposure to antigay hate speech or bullying as correlates of suicide ideation or attempts in youth (Haas et al., 2011). These studies have inspired a set of interventions focused on bullied youth: enactment and enforcement of antibullying policies, expansion of gay–straight alliances, and Internet-based campaigns such as It Gets Better (Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006). Such interventions are undeniably important for future generations of sexual minorities; however, stopping antigay bullying may be too little and too late for GLB adults who have accumulated a lifetime of social stress related to sexual stigma. Moreover, acute antigay stressors (such as bullying, harassment, or discrimination) are infrequently cited as causes of suicide attempts among GLB adults, when inductive approaches are used (Wang, Plöderl, Häusermann, & Weiss, 2015).

Qualitative research that exhibits the stories of sexual minorities who have experienced suicidal thoughts or actions offers a remedy to these limitations. In particular, unstructured narrative approaches complement quantitative studies by telling us how gay people themselves make sense of their histories of suicide attempts and how they convey these sensibilities to others. Survivors of suicide attempts can share previously unrealized ways of living and coping, and new strategies for preventing suicide. These strategies may be distinct from biomedical or psychological interventions and contextualized in ways that will ensure they are relevant and effective for gay people (Hjelmeland, 2016).

Method

Dialogical Narrative Analysis

Our interest in narratives as shared “templates” for understanding socially determined health phenomena led us to a particular methodological approach, offered by medical sociologist Arthur Frank (2010). Dialogical narrative analysis starts with the premise that stories are powerful, but can be dangerous, particularly when they become monologs, thereby forestalling other stories from being told. Researchers can mitigate this danger by entering a discussion with multiple stories rather than getting caught up in a singular story. In this article, we distinguish between a narrative and a story, using the convention established by Harrington (2009) and followed by Frank: Stories are unique individual accounts of personal experiences and events; by contrast, narratives are more basic, general templates that are passed through cultural communications (e.g., films, books, popular media, conversation), or “resources from which people construct the stories they tell and the intelligibility of stories they hear.” For example, the “quest” (or journey) is an old and familiar narrative, while Dorothy’s circuitous and particular return trip to Kansas in The Wizard of Oz is perhaps better termed a story.

Frank’s (2010) approach is not prescriptive with regard to methods but rather offers several guiding principles: first, that stories are always told in dialogue, and consequently, that no one individual’s meaning is final; second, that “people tell stories that are very much their own, but they do not make up these stories by themselves” (p. 14). In other words, storytellers borrow from stories that are available to them. Frank argues, in fact, for a converse logic, by which narratives are the ones borrowing the storytellers. By extension, narratives are conceived as dynamic, growing, and adapting, as they are repurposed and reimagined by the persons they emplot. A corollary to this tenet is that narrative researchers try to understand how stories act, rather than treat stories as data (Williams, 1984).

Sample and Data

We recruited a purposive sample of seven gay men who had attempted suicide as adults and invited them to share their life stories in one-on-one interviews. We focused the present study on individuals who identified as male, given the potential influence of gender roles and expectations on suicide attempts (Canetto & Cleary, 2012), the persistent gender-binary socialization that renders adult lesbian/gay life socially stratified (Eliason & Schope, 2007), and Salway’s own experience as a gay man. We were more flexible with regard to sexuality and included any man who identified as gay, bisexual, queer, two-spirit, or questioning. We required that interviewees be 30 years of age or older and have attempted suicide after age 21 but not in the past 2 years, to ensure they spoke about suicide attempts that occurred as adults and had sufficient time since their last attempt to seek care or support, if needed. Being two years post-suicide attempt was also intended to reduce the risk of the individual still being in a vulnerable or precariously suicidal state and, thus, reducing the risk associated with participating in the research. We recruited participants using local gay health and HIV service organization newsletters and social media (n = 5), flyers in gay businesses (n = 1), and word-of-mouth (n = 1). Study advertisements prompted prospective participants to respond to the following call: “As many as one in five gay and bisexual men have attempted suicide. We don’t know why.”

We talked with each potential participant by phone for 15 to 30 minutes, prior to each interview, to explain the purpose of the study, answer questions, and ensure the participant met all inclusion criteria. We asked about prospective participants’ current state of suicidal ideation and planning, and also about reliable professional and personal supports, to refer prospective participants to a professional counselor, if necessary. A total of 12 individuals responded to advertisements; three were ineligible due to age or having not attempted suicide, and two opted not to participate after the telephone screening.

All interviews occurred in a private office and lasted 1 to 2 hours. All participants provided written consent. Salway opened interviews by disclosing his identity as a gay man1; this brief discussion served to build rapport through transparency and to improve the quality of the interview by acknowledging potentially shared experiences as gay men. The interview guide was unstructured, with only two questions: (a) “In your own time, tell me your story about attempting suicide. Please include any events you think are important in your understanding of why you tried to kill yourself,” and (b) “What relationship, if any, do you see between your sexual orientation and your suicide attempts?” asked later in the interview, only if the topic did not arise. Interviews proceeded in a conversational manner; open-ended probes and follow-up questions were used to encourage storytelling and increase the level of description (Holstein & Gubrium, 2004).

Interviews were audio-recorded. We wrote immediate impressions after each interview, capturing nonverbal language, emotions, salient points, and emerging thoughts, and then transcribed audio-recordings verbatim. We then verified transcripts for accuracy by re-listening to recordings and re-reading transcripts. In addition, we wrote memos throughout analysis to work through preliminary ideas and to explore our own subjectivities (Heron, 2005).

We administered a three-question suicide risk assessment at the start and end of each interview to assess participant safety, as recommended by Reynolds, Lindenboim, Comtois, Murray, and Linehan (2006). No participants indicated elevated suicide risk either before or after the interview; however, all participants were given a referral sheet with contact information for the local crisis center and local gay health organizations offering free counseling, should they wish to access these resources in the future. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board.

Analysis

Analysis was iterative, inductive, and nonlinear. We conducted one interview per month between August 2015 and March 2016, allowing ample time between interviews for reflection and analysis. A turning point in analysis occurred after the seventh interview. The seventh participant explained his motivation to participate as follows:

I attended a conference about a year ago. I almost fell off my chair when [I heard] the stats on gay men, who were committing suicide . . . And it got me questioning it. D’you know? And then, there was a flyer going around work, about gay men thirty plus [years of age] who were attempting it, and it said “we don’t know why,” and I said to the director, “what do you mean they don’t know why?! Of course they know why!”

Reflecting on this participant’s indignation about the study’s premise (“Of course they know why!”), we began to acknowledge the particular ways in which the participants were motivated to step forward and share their personal stories. Faced with this conspicuous aspect of the study dynamics, we began to interpret participant stories as “companions”—to use Frank’s (2010) language—whether good or bad ones, that served the participants in making sense of the relationship between sexual minority status and suicide featured in the study pitch.

We focused our attention to stories at the intersection of sexuality and suicide, guided by dialogical narrative analysis. We exploited the insider/outsider dynamics of the authors’ dyad (Kanuha, 2000)—Salway sharing a gay male identity with participants, Gesink being an “outsider” to this community (heterosexual female mid-career with adolescent children)—and used these dynamics to increase both the rigor and validity of our findings. We proceeded through cycles of engagement with the participant transcripts/audio-recordings and multiple empirical sources and narrative contexts—similar to “analytic bracketing” (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009). Popular sources included academic journals (Hammack & Cohler, 2009; Robinson & Greven, 2001), gay literature (Monette, 1993), press reports (Clementi, 2012; Perelle, 2010), blogs (Clark, 2014; Simpson, 2016), short stories (Wong, 2015), books about the history of gay suicide (Rofes, 1983), films with gay characters (Russo, 1981), and a play about “gay heritage” that toured Canada while we conducted interviews (Dunn, Kushnir, & Atkins, 2016). Many of these references were suggested by study participants. Thus, we developed and revised our interpretations of participant stories with an eye to where their stories converged with others we had heard, either across the interviews, or in our own research and field work. Because we began with the assumption that storytellers borrow existing narratives that are already out in the world (Frank, 2010), we conceived of our analytical work as finding new expressions of existing narratives, in the voices of men we interviewed.

We asked the following questions, adapted from Frank’s approach, to advance analysis:

What narratives are used by the participants? And for each narrative, what is its genre? What characters, settings, and conflicts are central to the narrative?

How does the narrative position or preclude matters of sexuality, and of suicide?

What is the narrative’s effect, especially for the people emplotted by it? And, particularly relevant for the goal of suicide prevention, how does the narrative make life livable?

Basic structural elements common to most narratives include an abstract, orientation (who? when? where?), conflict, resolution, and sometimes evaluation (Frank, 2010; Labov & Waletzky, 1997); we indicate these elements, where relevant, in our analysis and presentation below.

The narratives we identified were a function of our own experience—enabled and limited by stories we had already heard (Boyd, 2009). Thus, we increased the credibility of our interpretations using peer debriefing and member checking. This included presenting results to friends, colleagues, mental health professionals, gay community workers, and the participants themselves. We asked readers to indicate whether they recognized the narratives and to describe their interpretations of the narratives with respect to suicide. In addition, we asked participants whether they agreed with our interpretation of quotations from their respective interviews. We reconsidered our interpretation and presentation of the narratives in light of disagreements. We arrived at a “repertoire” of gay suicide narratives, which we present as a tentative groundwork to which other narratives may be added in the future.

Results

Participant Summary

By definition, all seven participants who shared their stories identified as gay, bisexual, or queer at some point during their lives, though sexual identities were fluid. For example, one participant identified as bisexual for most of his life and only recently adopted a gay identity. Five of the seven did not adopt a gay/bisexual/queer identity until after age 35. Gender identities were also fluid; three participants described an internal feminine gender identity, despite a lived male identity and appearance. Participants ranged from 30 to 74 years of age.

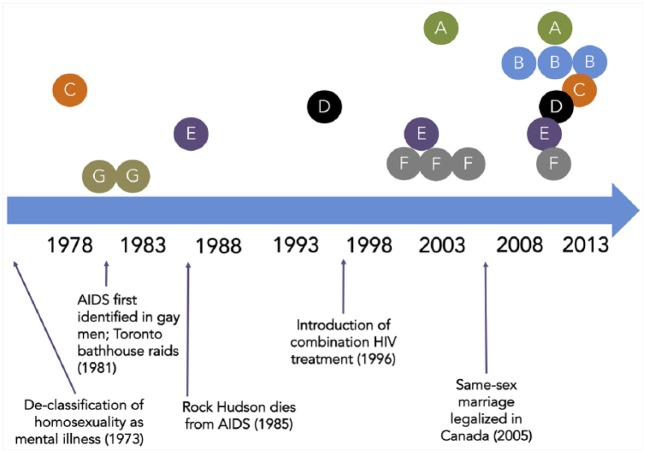

Six of the seven participants attempted suicide in the past 8 years, and most had previous suicide attempts that occurred during particular historical contexts, such as those marked by frequent police raids of gay bars and bathhouses, or lack of effective treatment for AIDS (Figure 1). Each participant reported two to four suicide attempts during their lifetime. All attempts were associated with intent to die; however, means, severity, and injuries associated with attempts ranged widely, with some attempts better classified as a detailed suicide plan (including method, time, place) without attempt. Six of the seven participants were taken to a health care facility immediately following at least one attempt. Participants described past and ongoing work managing mental health-related struggles, which included depression (most commonly), anxiety, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and paranoia. These terms are taken directly from the transcripts and may not constitute clinical diagnoses, though many were borrowed from interactions in which health care professionals offered a diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 1.

Historical context of suicide attempts described by seven gay men (each letter in the top portion of figure represents a suicide attempt reported by a study participant).

Toward a Repertoire

Pride narrative

Several participants arrived at the interviews—notably responding to our study pitch regarding a statistical association between sexuality and suicide—assuming that we perceived suicide attempts to be in direct response to antigay stigma (e.g., persecution or bullying, as exhibited in Turing’s and Lucas’s stories). These participants reacted to this perception by denying any connection between their sexuality and suicide attempts. One participant stated,

A couple people have asked me, “does your suicide attempt have anything to do with the fact that you’re gay?” I said “no . . . being gay had nothing to do with my suicide attempt.” Absolutely nothing. I know some people commit suicide when they realize they’re gay. It’s like, “what’s wrong, I’m gonna shoot myself.” I never felt that way. That’s what kept me going. And ever since I’ve come out, I’ve never attempted suicide yet. So maybe if I came out earlier it would have been easier.

This participant attempted suicide before coming out and describes having not attempted suicide since, suggesting a potent relationship between concealed sexuality and suicide, yet he himself resists drawing any connection between the two. This reluctance to attach a gay identity—when realized as positively valent—with suicide attempts is supported by a robust pride narrative.

Pride narratives are ubiquitous in gay literature (Forster, 1971; Monette, 1993; White, 1988), “stage” theories of gay identity development (Eliason & Schope, 2007), and, of course, pride parades (Macdonald, 2016). The conflict in a pride narrative typically begins with pervasive societal stigma. The protagonist of a pride narrative must reject this stigma to eventually claim a gay (or bisexual, queer, or lesbian) identity, free of shame (Klein, Holtby, Cook, & Travers, 2015). Pride is notably the culminating stage of clinical psychologist Vivienne Cass’s GLB identity stage model (after identity confusion, comparison, tolerance, and acceptance), often marked by the individual’s “unwillingness to accept the [antigay] stigma as his or her problem” (Eliason & Schope, 2007). Pride itself is, thus, the resolution to this narrative.

One participant came out as gay 3 years before his interview and spent much of his interview outlining this experience, in close step with a pride narrative. His story started with an internalized shame attached to his sexuality, based on messages he received from his father:

[My dad] always told us, all his life he said, “gay guys are a bunch of mentally sick goddamn fruits, and they should be taken to an island out in the Pacific and should be annihilated.” And we were sitting there, both my parents one day, and we were visiting, and a show came on, there was two gay guys and they mentioned that these two are a gay couple, and my dad suddenly said, “if I ever found out any of my kids was a goddamn fruit, I’d disown him from my will.”

As this participant realized he was gay, he sought connection in the gay community:

Actually it was [local gay health organization] that really helped me to come out, that it was OK. It was, it felt, it was so much easier than I thought it was going to be. I was talking to a friend of mine a couple years ago, and he said “why are you still here today?” and I said “because I know I’m gay.” I said “the only reason I’m here is because I know I’m gay. I’m very proud of that. I’m happy with that.”

He went on to describe how a particular support group at the gay health organization encouraged him to adopt a gay identity and normalized this identity for him.

The Wednesday group was the familiar faces all the time, same facilitators for about a year and a half. All the same guys. Regular guys would show up. I started feeling very comfortable with them, to open up, to my feelings. So that’s when we were doing the coming out sessions as well. And I felt very comfortable coming out to these guys.

Eventually, he started to test the waters with his oldest brother:

So, uh, I asked my oldest brother, I said “if you ever found out one of your brothers was gay, would you care?” He goes, “no, why would I?” He goes, “I’ve got gay friends. I just want you guys [his brothers] to be happy, that’s all . . . .” I said “so you wouldn’t care if he [one of your brothers] walks in with his boyfriend one day and introduces him as his boyfriend?” He goes “no,” he goes “if I find out one of my brothers is gay, I want to meet the boyfriend . . . .” So I think he knows. Because he doesn’t ask me if I have a girlfriend anymore.

This participant’s discussion with his oldest brother is significant in at least two regards. It helps to countervail some of the hateful language of his father, and it signals the arrival of something analogous to the GLB identity stage model’s “identity acceptance” stage, in which the protagonist begins to see the possibility of social acceptance (Eliason & Schope, 2007). Later in the interview, the participant described how he arrived at the confidence referenced in the pride stage:

. . . And now, if someone walked up to me on the street and said, “are you gay?” “Yah I am.” I’m not ashamed of it. I’m not afraid of it. I go to [name of local suburb], and actually I was at the [name of suburban transit] station, and a guy started talking to me, he said, “do you like women?” I said, “no, you mean sexually? No.” He goes “why not?” I said “because I’m gay. I like men.” He goes “oh, ok.” He was fine with it. After he left I’m like “holy crap, I’ve never done that before!” (laughs)

The pride narrative resists any notion of a causal relationship between sexual orientation and suicide and, thus, can be a powerful form of coping, as it was for this participant. It should be noted, however, that the pride narrative is also rigid. Those who cannot comply with it are “at risk” for suicide, by failing to achieve the supportive connections offered by gay community socialization, like that described by the participant quoted earlier (Cover & Prosser, 2013). If the pride narrative emerged as a resilient and resistant plot to protect against suicide, the following four narratives offer stark contrasts that serve to justify or explicate it.

Trauma and stress narrative

The next narrative we identified in the interview transcripts was one we were perhaps most primed to find during analysis, having been immersed in a predominantly psychology-focused literature on the topic of suicide. We have termed this general narrative trauma and stress. Trauma and stress were referenced by numerous participants, and clearly articulated by one participant who gave the following abstract to the story of his first suicide attempt:

I converted to being [HIV]-positive, went through personal financial bankruptcy, went through divorce, went to [local bridge], three in the morning, uh, that was the ultimate, it was just going to the middle of the [local bridge] and just taking a look, just wanting to jump . . . I had other thoughts before, ever since I was a kid, where, when the anxiety got the better of me, it just seemed like when I was in Grade 7 or Grade 8, Grade 9, umm, I think it would be episodes of trauma. And that really reinforced my sense of anxiety around different things, about can I do it? Can I make it [survive]?

Later, this participant evaluated his suicide attempt story, through the lens of what he has since learned about the relationship between trauma and stress:

I sometimes wonder if this is all posttraumatic stress, about having to live through the whole secret [about being gay], actually coming out, becoming bankrupt, becoming divorced, things like that . . . and when I’m cycling really low, about everything, . . . all my concerns get grouped together, it gets overwhelming, and I can’t cope. And that’s where I’m going to harm myself because I just can’t do it.

The primary conflict in a “trauma and stress” narrative is the need to find a way to manage the accumulation of stress stemming from trauma, and the climax of this conflict (if not resolved), is suicide, or attempted suicide. Narrative resolution comes only through finding coping strategies to manage the stress and attendant psychological struggles. In many versions of the narrative, this is achieved through a clinical or therapeutic strategy, such as counseling, group therapy, or medication. In others, the resolution occurs by finding social support in places that acknowledge and work with the effects of trauma and stress. For example, after going on disability, one participant found support by volunteering at a local gay health organization:

They’ve [the organization and staff] always been very supportive of me . . . when I was thinking of getting back into trying to work, I immediately thought maybe I should go volunteer there, and they said “yes, yes please come back.” . . . and if I have a problem or a moment, or something that’s bothering me, I can easily get, take some time off.

This volunteer work removes the additional stress associated with paid work while providing a social network and allowing him to make personally meaningful contributions to his community.

Although this general narrative is not particular to gay men, it was often expressed by participants in relation to fundamental, early-life experiences of sexual stigma or shame. For one participant, this fundamental sexual stigma was compounded by other secrets and stigmas:

I’m withholding a big major secret. Ok. There’s a stress there. And then I’m withholding a secret of being gay. And that’s layered by, I’m withholding a secret about my career, my profession, another layer is that I’m withholding my secret about being bipolar—it’s called stigma. And I’m really attempting to get away from that stigma. But being gay was really, I stop and think, and if I was, 20–20 hindsight, if I was comfortable being gay at an earlier age, would all this have happened? You know, I’ll never know, but invariably I’m inclined toward saying everything else would not have happened because it’s living my life truthful.

Another participant traced his trauma and stress narrative to early-life stigma, stemming from a physically and verbally abusive father:

My dad said to me, several times, “if you’re one of those fruits, I don’t want to hear about it.” I said, “ok fine, you’ll never hear it,” and I don’t think I’ll ever tell him. I’m afraid to tell him now. So um, yah, part of my PTS—or part of my suicide attempt is I had—or have—PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder. And that’s actually, my first suicide attempt, that’s how they found it. They found PTSD, I was diagnosed with PTSD.

All participants had interactions with the mental health care system—some supportive, others less so—and they often borrowed ideas from mental health care providers to make sense of their experiences of suicide. Thus, it is not surprising that this narrative appeared so frequently throughout the interviews. The narrative itself is nonetheless significant for the purposes of this study because it offers clear opportunities for making life livable for suicidal gay men. The trauma and stress narrative not only helps by finding ways of coping with the stress but also by acknowledging the role of trauma, and in the case of the men we spoke with, by particularly acknowledging the fundamental effects of sexual (antigay/bisexual) stigma on the lifetime mental health of sexual minorities.

Given some participants’ attention to sexual stigma as a source of trauma, it is worth acknowledging the overlap between trauma and stress theories and minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003). As with theories of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), minority stress centers around the mechanisms by which negative appraisals of external threats lead to ineffective coping strategies, such as rumination or social avoidance. However, in the case of minority stress, the external threat is the continued stigmatization of being a social minority. Minority stress theory has begun to enter the purview of clinical psychologists and counselors in recent years, especially with the American Psychological Association’s (2016) adoption of guidelines on practice with GLB clients, which foremost assert that psychologists should “strive to understand the effects of stigma (i.e., prejudice, discrimination, and violence) and its various contextual manifestations in the lives of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people.” The prominence of this narrative in interviews with gay men who have attempted suicide suggests it should continue to be explored by mental health professionals.

Memorial narrative

Several of the narratives uncovered were in part functions of the generational experiences of the storytellers. The youngest participant interviewed offered a variation of a pride narrative but one that was more concerned with retrospective aspects of a gay identity and one that is increasingly endorsed by younger generations of gay and queer persons. The retrospective nature of this type of narrative is termed a memorial account (Cover & Prosser, 2013), and is characterized by a sense of having always known one was gay, from early childhood. This participant provided two parallel memorial accounts: one of a fundamental and fixed sexual identity, the other of a mother who “must have known” about the participant’s gay identity all along:

I’m Roman Catholic, so my family is very bible-oriented. God, he’s our savior, and I’m like, “umm, he doesn’t even exist, so why’re we believing in this bible because it doesn’t make sense to me.” I hated it. And being in a Roman Catholic school, elementary school, it’s kind of hard to be yourself, like when I knew I was gay at the age of 8. Umm, and well actually I knew it sooner than that because I remember when I was 4 . . . I was playing dress-up with my neighbor, and I called my mother, who, she kind of didn’t want to come out. I’m like, “mom, you have to come outside cause I’ve got a big surprise for you!” OK, so she comes out and I’m wearing these hideous fucking—oh my god—I wore stilettos, 10 sizes too big, a mini-skirt, and I had these little short pigtails and really bad make-up. [laughs] (Interviewer: Baby’s first drag?) That’s right! I was like, “mmhmm, look at these!” But I mean, my mother had a hard time with me being gay, which made me more depressed . . . but going back, my next door neighbor and I were side by side, down the porch, down the sidewalk, up to our house and into our house, and these were boots that were not tied up, like literally I’m dragging my feet. My mother looked and she’s like, “fucker did it better than I do and I’m a woman!” And she knew from that point on that I was different, but it was hard for her to I think help me in that sense.

This memory was a linchpin of the participant’s narrative, as became apparent later in the interview, when he was asked to reflect on his coming out experience:

[looking up] Oh mother, I love you, but please don’t show up. So when I went and told my family, I was living in a group home . . . the last person I talked with was my mother . . . when I called my mother, I asked her two questions. I go, “mom, would you still love me no matter what? If I robbed a bank, would you still love me? Mother, would you still love me if I ended up in jail?” I had to think of these worse case scenarios. “Well, would you love me no matter what, if I was gay and loved a man?” [pause] She uh, there was a pause, and she’s like, “no, I don’t give birth to fags, you’re not my fucking child, don’t ever call me again,” and she hung up the phone, and I was livid. I was in tears because I was not expecting that because I remember when I was four, about the whole high heel thing, there’s no way my mother could ever forget that . . . so when I’m sitting in the group home . . . all I can hear is the phone going “beep, beep, beep,” I’m still continuing on this whole conversation, with a dead phone with nobody on the other end, and I’m like “well, OK mom, well it’s nice talking to you. I need to go now cause I gotta go back to school” and hung up the phone. And I remember leaving and I bolted.

By cementing this notion of having always been gay (“there’s no way my mother could ever forget that”), the participant identifies not only the injustice but also the illogic of his mother’s rejection.

Memorial GLB narratives—notably prevalent within the repository of It Gets Better videos (Grzanka & Mann, 2014)—may risk essentializing a queer identity and, hence, restricting fluid or nonlinear expressions of sexual and gender identity (Cover & Prosser, 2013; Klein et al., 2015). For the participant quoted above, however, the permanent aspect of the memorial narrative is a source of strength. His identities, as gay and as a drag performer, are bolstered by his age-four memory, and his mother’s positive reaction to “baby’s first drag.” Later this participant explained how this connection to drag (and music) prevents suicide:

I always tell people, like if I’m at home and I’m not volunteering or if I’m not in the community or I’m not doing drag for like a month or two, you might want to come see what’s wrong with me cause that would be the sign that I’m not OK. . . . I watched a lot of my friends when they were doing theirs [reference to friends’ suicide attempts and deaths], and even for myself, music is one of the best things for any type of situation, I find. And I mean, I think that’s why I do drag. Music is a way of letting go of emotion.

In the pride narrative, the protagonist adopts a sexual identity through a process of conflict (coming out) and resolution (i.e., conquering societal homophobia). In the memorial narrative, the protagonist’s sexual identity is crystallized from the start; thus, the narrative conflict is one of maintaining a fixed identity through the use of reconstructed memories. The significance of this process of maintaining a memorial identity is illustrated by Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (Bechdel, 2006). Bechdel, herself a lesbian, melds a series of memories and flashbacks in comic book form, to make sense of her father’s death, which she interprets as a suicide in response to his closeted homosexuality. Memorializing Bechdel’s father’s sexuality is vital to Bechdel, who was herself coming out at the time of her father’s death. For both Bechdel and the participant quoted above, the memorial narrative maintains familial connection through the persistence of a fundamental sexuality.

Outing narrative

Many of the participants came of age during times when the Royal Mounted Canadian Police and other Canadian police surveilled gay citizens and raided gay bars and bathhouses (Gollom, 2016; Kinsman & Gentile, 2010), and during the early years of the AIDS epidemic, when AIDS diagnoses or deaths “outed” previously closeted gay men (Crimp, 1992; Figure 1). It is not surprising that their suicide stories referenced aspects of surveillance, entrapment, and other homosexual-secret-finding methods used by authorities in the mid- to late-20th century, now widely considered unjust. One account of how the political pressure of surveillance and entrapment can result in a gay suicide is provided in the story of Alan Turing, described in the “Introduction” (Hodges, 2014).

Participants offered their own recreations of entrapment, surveillance, and AIDS-outing narratives, generalized here as “outing narratives.” For one participant, who had already lost his sense of identity from a career downfall, the rumored release of the secret about his sexuality was accompanied by what he described as a feeling of unjust exposure. The rumor led his wife and (now adult) children to renounce him and sever all ties with him, leaving him isolated and depressed: “Totally shunned; I have no family.” This participant explained that the depression from his family’s rejection led to his first planned suicide attempt, in which he intended to drive his car off a mountain pass road.

Over the course of the interview, this participant shared a series of stories about sexual encounters, mostly with men married to women (and having sex with men unbeknownst to their wives), whom he met through telephone-based advertisements. He often coached these men on how to be circumspect in their sexual interactions. After one of these men tried to coax him into having sex in the backyard of his home, the participant admonished him: “And I said, ‘will you smarten up?!’ He had five kids. I said, ‘what would you do if one of the kids came into the grass while I was rogering you?’ I mean, dumb. I said, ‘please, please, please smarten up.’”

This participant’s concern for discretion also manifested as fear of being caught or outed, especially by members of his family. He often referenced this suspicion as “entrapment”:

I had five married fuck buddies . . . all responses to my ad! Which I think the ad might have been listened to by somebody that I wish it hadn’t . . . I think it was entrapment! And of course that probably solidifies their [his family’s] attitude to me. Because they won’t talk to me. They won’t have anything to do with me.

Entrapment typically implies that an authority (such as a law enforcement agent) has tricked someone to commit a crime (in this case homosexual acts). This aspect is missing from the participant’s story, though his story exhibits two other central features of entrapment: a sense of being caught and a feeling of injustice, from thinking he was in a safe and secure environment when meeting other men for sex, not realizing he could be outed by public onlookers. More significantly, this participant feels a sense of betrayal and loss from his family’s rejection.

Another participant offered an outing narrative that positions his suicide attempt within a similar context of homosexual “witch-hunting”:

So [sighs], things started to break with me 30 years ago. I was reading the [university] newspaper just by chance, and I read where some [fraternity] boys crashed a gay and lesbian beer garden and were trying to pick fights and hurtling verbal abuse and all this crap. And I kind of got the feeling that, the reason they did that was they were trying to see if I was there . . . And that’s how bad the homophobia was. They’d go after you. They thought, “he’s one of us but he’s queer, so we’re going to kill him, we’re going to beat him up.” So that, that’s like around the time the paranoia started for me.

After this participant felt the paranoia was taking over his life, he started seeing a psychiatrist who prescribed him a number of different medications, none of which he felt he could handle. He described becoming “unglued” and vandalizing buildings, which led to a police arrest and then to his psychiatrist admitting him to the hospital. He described a series of four hospital admissions and discharges in a row, within 1 year from the events related to the gay and lesbian beer garden. The cumulative embarrassment, from the rumors about his sexuality to his hospital admission, eventually drove his first suicide attempt:

And frankly, the first suicide attempt, I wasn’t feeling sorry for myself . . . I was just damned embarrassed. I wanted to get rid of myself . . . the whole thing about getting discharged . . . going off the medication again, being embarrassed, getting a bunch more medication, and just swallowing as many pills as I could at one time.

The historical context of AIDS is notably central to his story:

I broke up with this girl I was supposed to marry . . . on Christmas Eve, ’84. So in the new year I thought I’ll quit smoking, start jogging, lose some weight, get in shape, eat better, become a better me. All laudable goals, considering I just lost the person I was supposed to marry. The problem is, it worked too well. I lost like 60 pounds in two months, jogging every night. So my whole gut was flat again. However, it’s right at the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic. AIDS is a gay man’s disease, not a woman’s disease. The only known symptom is massive weight loss in a short period of time. Some people are starting to talk about me. “Oh, maybe he fools around with guys a lot.” And I guess my girlfriend had to have a blood test, stuff like that. That would never occur to you nowadays. It makes you paranoid! The whole Linda Evans [TV soap opera co-star with Rock Hudson], what’s his name Rock . . . (Interviewer: Hudson), yah, Rock Hudson. “Can I get it from kissing? I kissed him once, can I get it from kissing?” It’s ignorant. It made people like me paranoid. And then later that year in the fall was when the [fraternity boys] crashed the beer garden, so I guess they were looking for me. “The lady’s turned gay finally! And he’s found his people to take him in, gays and lesbians on campus.”

This participant’s invocation of Rock Hudson’s story is significant because it signals the different ways in which the context and methods for outing changed over the course of the late-20th century, yet continued to inspire a sense of injustice in the men affected by it. Hudson, a popular actor, Hollywood heartthrob, and previously closeted homo/bisexual, was outed by the popular press in 1985, with the news that he was dying from AIDS (Meyer, 1991). This marked a turning point in the epidemic. Hudson’s death and outing increased awareness and support for the AIDS epidemic, while also substantiating the notion that “AIDS equals gay” (Crimp, 1992). The outing tactics of police in the mid-20th century were now taken up by the general population in new ways, using AIDS-related assumptions and accusations.

Historically, suicide was associated with homosexual entrapment and blackmail, as an unfortunate, emplotted ending: Become publicly revealed as a homosexual, or else end your life (Rofes, 1983). Many chose the latter ending. Indeed, multiple suicides occurred among the gay men arrested in the Toronto bathhouse raids of 1981 (Dubro, 2016). For the participants we interviewed—who survived the suicide plans and attempts they discussed—suicide was not an inevitability. Nonetheless, suicide fits logically, if not comfortably, inside their narratives as protest against an unjust system, a system that cannot accommodate their deviance.

On first glance, the outing narratives may not appear to serve the storytellers as beneficially as the previously cataloged pride, trauma and stress, and memorial narratives. But the participants’ embrace of these narratives suggests otherwise. Outing narratives, first, allow the storytellers to make sense of their own histories of suicide thoughts and attempts, just as the trauma and stress and memorial narratives do for the participants who endorsed them. But more importantly, outing narratives ask the listener to acknowledge the injustice of the historical conditions that allowed for entrapment and surveillance and, in so doing, derive for the storyteller a certain resilience.

Postgay narrative

The modern gay rights movement has worked toward goals of simultaneously assimilating gays and lesbians into heterosexual society—take, for example, the recent push for legal same-sex marriage in the United States—and diversifying the identities represented under the queer umbrella, symbolized by the progressive additions of “B” (bisexual), “T” (transgender), and “Q” (queer) to the LGBTQ acronym, thus allowing younger generations of LGBTQ people to opt to use labels like queer or pansexual (or no labels at all) to describe their sexuality (Ghaziani, 2011). The result of these two goals is the emergence of a “post-gay” assertion—namely, that gay people need not exclusively define themselves on the basis of an immutable gay identity—and activists and social critics within and beyond the LGBTQ umbrella have rallied against this trend (Conrad, 2014; Simpson, 2016). The postgay narrative presents a particular conflict for someone who would otherwise connect with shared gay experiences but feels lost or even dismissed in the context of a “post-gay collective identity” (Ghaziani, 2011; Klein et al., 2015).

One participant asserted this narrative when the interviewer showed him the recruitment flyer for the study, and asked him to give the answer to his statement, “Of course they know why!”

(Interviewer: If you had to summarize [the why] in a few sentences or a paragraph, how would you describe it?) I believe that gay men today are being erased. We’re supposed to be initialized under LGBQ, but in the din [we’re] being erased, from the gender studies departments in the universities, right? Um, the closure of the traditional locations where we had colonized so we could meet together safely, the bars, the baths, the discos. They’re closing, right? I think it was Mark Simpson out of the U.K. who said, the rise and fall of the culture, we have seen the fall of gay culture. We have been so assimilated, which is probably a mistake. History will prove this has been a mistake for us. And I think that the older gays don’t know what’s hit them, right? . . . And so I’m not sure what the answer is because I think that the older, the voices of those who are up there in age—that would be me, I suppose, but—we need to be, I mean with all respect to Savage and It Gets Better and all that shit, it’s not getting better! . . . I think for the sake of preserving life, we need a whole new focus from the older gay male, and maybe lesbian groups, to intervene here.

For older generations of gay men, in particular, the threat of being left behind in a postgay identity movement can translate to social isolation, and in some cases suicide. A gay writer from Toronto contacted us during this study to share a blog he had prepared that indexes older gay men who have committed suicide. On his blog, he responds directly to the question of why? specifically invoking the postgay identity shifts (“young queers”) as the smoking gun:

We survived three holocausts already—family rejection, AIDS, and now young queers who want us dead. Huge numbers of our gay-male friends, who would be eldergays in their own right, died of natural causes, suicide, AIDS, or other factors; many of us are alone. A large percentage of us suffer from depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or other mental-health conditions with a predisposition to suicidal thoughts or actual suicide. (Clark, 2014)

The “erasure” of “older gays” that this participant references leads to suicide through the cumulative process of social loss explicated by Clark: Family rejection, the AIDS epidemic, and the silencing of voices and identities of older gay men have left many of these men socially isolated and, thus, prone to suicide.

Conclusion

The sharing of narratives concerning any struggle for health and well-being—whether it be suicide, AIDS, or some other threat—leads to a collective belief system about the struggle in question (Murray, 1997), mobilization of political and social action (Frank, 2010), and community-based models of coping (Crimp, 1987). The greater our narrative resources on a given topic, the better prepared we are to collectively and individually respond (Frank, 2010). By expanding the collection of gay suicide narratives available, we enable more ways of making sense of, and living with, suicidal thoughts and actions in the context of sexual minorities’ lives.

Dialogue with the seven suicide attempt survivors who participated in this study yielded five narratives that go beyond the prevailing adolescent-bullying suicide narrative discussed at the start of this article. Some participants endorsed a narrative that, like the adolescent-bullying narrative, makes deliberate, if not direct, connections between a stigmatized sexuality and suicide attempts; the trauma and stress narrative enables its protagonists to seek acknowledgment of their trauma—often stemming from early-life sexual stigma—and thereby find ways of building resilience. Other narratives, however, confound the relationship between sexual stigma and suicide; for example, the pride narrative resists a direct connection between the two, obscuring that suicidal thoughts may have originated from the stigma and stress experienced during a pre-pride phase of concealment. The emergence of the pride narrative also serves as a testament to the prevalence of this narrative in gay life generally.

The remaining three narratives signal how notions of gay suicide follow seismic generational shifts that occurred in the experiences of gay and bisexual men over the course of the 40 years recollected in these participants’ stories (Hammack & Cohler, 2009). Historical narratives of outing appeared, reminding us that the felt injustice of sexual surveillance continues to resonate in the lives of suicidal gay men today. Memorial and postgay narratives demonstrated opposing reactions to shifting integration of sexual minority identity into mainstream society. The memorial narrative—particularly common among younger generations of sexual minorities (Cover & Prosser, 2013)—safeguards an otherwise rejected identity by asserting that the narrator and his family “always knew” he was gay, an assertion that is enabled by greater societal awareness of sexual minority identities. By making the gay identity a constant fixture in the narrator’s life, he can turn to it as a source of strength when feeling suicidal. Thus, one participant was able to derive reassurance and even confidence from his “baby’s first drag” memory, which time-stamped his identity at an early age. Meanwhile, the postgay narrative describes the detrimental effects of identity-related shifts in societal norms and politics. Older gay men feel invisible, exacerbating the social isolation that resulted from historical losses related to familial rejection and high rates of HIV and AIDS mortality.

Sexual identity concealment or (in)visibility features prominently in all five narratives. Concealment is not only most patently instrumental to the “outing” narrative—in which storytellers derived a sense of injustice from their early-life experiences with being outed—but also plays a key role in the pride, memorial, and postgay narratives. All three of these narratives concern securing a gay identity in the threat of erasure. Hence, some participants proclaimed a proud gay identity, another participant clung to the memory of his childhood gender-atypical drag performance, while yet another demanded that the voices of his generation of gay men be heard. One participant’s story poignantly expressed how concealment can be integral to the trauma and stress narrative by emphasizing the fundamental role of “withholding a secret of being gay.” The salience of sexual minority identity concealment and invisibility across all of these narratives suggests that identity concealment remains a potentially critical driver of the disparity in GLB suicide attempts today. This hypothesis is supported by other studies that find that nuanced aspects of concealed sexual identity management relate to suicide risk, and depression and interactions with health care providers (Adams, McCreanor, & Braun, 2013; Pachankis, Cochran, & Mays, 2015; Salway et al., 2018); additional research must investigate what aspects of concealment (e.g., social contexts, timing, attitudes, and generational experiences) contribute to suicide, and how.

Limitations

The stories presented within this article may or may not constitute real or perceived causes of the storytellers’ suicide attempts. As stated throughout this article, the findings are best construed as a collection of narratives repurposed by gay men who have attempted suicide. These narratives are not esoteric. They are commonly referenced in gay dialogues elsewhere and, thus, will look familiar to many readers. Nor do the narratives presented in this article originate with the participants we quote. The participants’ creative contribution is recasting these narratives in relation to their own life stories, highlighting particular experiences of suicide attempts and sexuality.

The narratives identified in this study are not exhaustive. The participants were diverse with regard to age, sexual identity, occupation, and socioeconomic position; however, only one participant was a racialized minority, and both authors are White. These findings would be complemented by other stories from Indigenous persons, immigrants, and people of color. Furthermore, our study was conducted in the particular context of a high-income North American country with relatively advanced legal and social rights for gay men; surely, gay suicide narratives will differ in other, international contexts.

Despite our intention to specifically sample male-identified persons, three of the participants expressed some experiences of nonbinary gender identities. There is much to learn from ending the pervasive habit of gender-stratifying queer health research, given the complexity and fluidity of gender. In addition, the narratives presented were a function of the historical contexts of the storytellers’ lives. While some of these narratives correspond to suicide attempts 20 or 30 years ago, it is important to note that six of the seven participants continued to struggle with suicide throughout their lives, attempting suicide again in recent years. Finally, we note that most gay men will not attempt suicide; thus, our intention with this particular set of narratives is to expand resources for those gay men who are struggling, while carefully guarding against any generalizations about gay men’s life stories.

How to Expand Our Narrative Resources

All of us concerned with gay suicide—starting not only with those who are struggling with suicide themselves but also with researchers, clinicians, public health officials, and community advocates—share a common goal of reducing suffering and ultimately preventing suicide. One means of achieving this goal is storytelling, and the dialogicial complement: listening. This seemingly straightforward activity is often stymied, as each of us (with good reason) interprets events around us through the “lens” of our own backstories (Johnson, 2016). Thus, the difficult task at-hand is to create and open space for new narratives; the challenge and promise of this task is reflected in the recent growth in narrative approaches to psychotherapy, organizational change, and conflict resolution (Gergen & Gergen, 2006).

How can each of the implicated parties named earlier do more to enable and expand storytelling and story-sharing when it comes to gay suicide? We have demonstrated how we think researchers can do this. For example, when we first encountered the pride narrative, our inclination was to reject it: These stories were replete with examples of how their sexuality related to suicide attempts, and we were confounded by their insistence that the two have nothing to do with one another. Re-listening to these stories in dialogue, however, revealed a distinct meaning that participants derive from a pride narrative, and therein an opportunity for us as researchers to represent this meaning to other stakeholders.

Reflecting on this study, we seek audience beyond researchers, in the nurses and outreach workers and activists who encounter and speak to issues of gay suicide every day. “Proceed by indirection”: This is Frank’s (2007) advice to those who undertake the clinical work of narrative reconstruction (another way to describe what all good clinicians do, as they help their patients find ways of living better). In other words, rather than suggest to suicidal persons that their stories are “good” or “bad” for them—an approach that is often used by well-intentioned helpers who follow a pathological model that results in clinician-directed treatment (Michel, Dey, Stadler, & Valach, 2004)—all of us engaged with this issue can work to make more stories available, and allow those who are suffering to choose among them. Narrative approaches to therapy and arts-based therapies may be two practical ways forward with this recommendation (Estefan & Roughley, 2013; Gysin-Maillart, Schwab, Soravia, Megert, & Michel, 2016); some of these methods have notably been tailored for use with gay or queer clients (Bain, Grzanka, & Crowe, 2016). The growth of the Internet as a medium to enable illness-oriented story-sharing—particularly for those affected by the stigmas of suicide and sexuality—is also promising (Kotliar, 2016). Ultimately our collective goal should be to enrich the narrative resources made available to those affected by suicide. These narratives may include those of pride and shame, trauma, erasure, fixed and fluid identities, and many others yet to be imaginatively recast.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful, first and foremost, to the seven individuals who generously shared their stories as part of this study. The following individuals provided invaluable feedback on earlier drafts of this article: Craig Barron, David Brennan, Olivier Ferlatte, Daniel Grace, Trevor Lanting, Brian O’Neill, Anne Rhodes, and Terry Trussler. We additionally wish to thank Darren Usher, the Community-Based Research Center for Gay Men’s Health, the Health Initiative for Men, and the Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention Center of British Columbia for their in-kind support.

Author Biographies

Travis Salway, is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of British Columbia and the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Dionne Gesink, is an associate professor in the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Salway conducted all pre-interview phone screenings, suicide risk assessments, and interviews; wrote analytic memos; and led analysis and manuscript writing. He additionally completed 100 hours of crisis response and suicide risk assessment training to prepare for interviews. Gesink supervised Salway, provided methodological guidance, actively participated in analysis, and contributed to manuscript writing.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Travis Salway’s doctoral research was supported by a Vanier Canada Research Scholarship.

ORCID iD: Travis Salway  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5699-5444

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5699-5444

References

- Adams J., McCreanor T., Braun V. (2013). Gay men’s explanations of health and how to improve it. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 887–899. doi: 10.1177/1049732313484196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2016). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist, 67, 10–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain C. L., Grzanka P. R., Crowe B. J. (2016). Toward a queer music therapy: The implications of queer theory for radically inclusive music therapy. Arts in Psychotherapy, 50, 22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J. (1948). Sonny’s Blues. In Going to meet the man (pp. 101-141). New York, NY: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bechdel A. (2006). Fun home: A family tragicomic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Nasuti L. J., Mays V. M., Cochran S. D. (2016). Suicidality and sexual orientation: Characteristics of symptom severity, disclosure, and timing across the life course. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86, 69–78. doi: 10.1037/ort0000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd B. (2009). On the origin of stories: Evolution, cognition, and fiction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canetto S. S., Cleary A. (2012). Men, masculinities and suicidal behaviour. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, June 21). LGBT youth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth.htm

- Clark J. (2014, July 13). Eldergay suicides. Retrieved from https://eldergaysuicides.wordpress.com/about/

- Clementi J. (2012, February 1). Letters to my brother. Out. Retrieved from https://www.out.com/news-commentary/2012/02/01/tyler-clementi-james-letters-my-brother

- Conrad R. (Ed.) (2014). Against equality: Queer revolution not mere inclusion. Oakland, CA: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cover R., Prosser R. (2013). Memorial accounts. Australian Feminist Studies, 28(75), 81–94. doi: 10.1080/08164649.2012.759309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crimp D. (1987). How to have promiscuity in an epidemic. OCTOBER, 43, 237–271. doi: 10.2307/3397576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crimp D. (1992). Right on, girlfriend! Social Text, 33, 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dubro J. (2016, February 3). Toronto’s stonewall. Now. Retrieved from https://nowtoronto.com/news/torontos-stonewall/

- Dunn P., Kushnir A., Atkins D. (2016). Gay heritage project. Canada: Buddies in Bad Times; Retrieved from http://buddiesinbadtimes.com/show/gay-heritage-project/ [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A., Clark D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason M., Schope R. (2007). Shifting sands or solid foundation? Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity formation. In Meyer I. H., Northridge M. E. (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities (pp. 2–26). New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Estefan A., Roughley R. A. (2013). Composing self on narrative landscapes of sexual difference: A story of wisdom and resilience. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 47(1), 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Forster E. M. (1971). Maurice: A novel. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. W. (2007). Five dramas of illness. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 50, 379–394. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2007.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: A socio-narratology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen M. M., Gergen K. J. (2006). Narratives in action. Narrative Inquiry, 16, 112–121. doi: 10.1075/ni.16.1.15ger [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziani A. (2011). Post-gay collective identity construction. Social Problems, 58, 99–125. doi: 10.1525/sp.2011.58.1.99 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gollom M. (2016, June 22). Toronto bathhouse raids: How the arrests galvanized the gay community. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/bathhouse-raids-toronto-police-gay-community-arrests-apology-1.3645926

- Goodenow C., Szalacha L., Westheimer K. (2006). School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 573–589. doi: 10.1002/pits.20173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanka P. R., Mann E. S. (2014). Queer youth suicide and the psychopolitics of “it gets better.” Sexualities, 17, 369–393. doi: 10.1177/1363460713516785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J., Holstein J. (2009). Analyzing narrative reality. Thousand Oaks: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781452234854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gysin-Maillart A., Schwab S., Soravia L., Megert M., Michel K. (2016). A novel brief therapy for patients who attempt suicide: A 24-months follow-up randomized controlled study of the attempted suicide short intervention program (ASSIP). PLoS Medicine, 13(3), e1001968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. P., Eliason M., Mays V. M., Mathy R. M., Cochran S. D., D’Augelli A. R., . . . Clayton P. J. (2011). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58, 10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack P. L., Cohler B. J. (2009). The Story of Sexual Identity: The narrative perspectives on the gay and lesbian life course. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195326789.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington A. (2009). The cure within: A history of mind-body medicine. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Heron B. (2005). Self-reflection in critical social work practice: Subjectivity and the possibilities of resistance. Reflective Practice, 6, 341–351. doi: 10.1080/14623940500220095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmeland H. (2016). A critical look at the current suicide research. In White J. H., Marsh I., Kral M. J., Morris J. (Eds.), Critical suicidology: Transforming suicide research and prevention for the 21st century (pp. 31–55). Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges A. (2014). Alan Turing the enigma. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein J., Gubrium J. (2004). The active interview. In Silverman D. (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method, and practice. doi: 10.4135/9781412986120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hottes T. S., Bogaert L., Rhodes A. E., Brennan D. J., Gesink D. (2016). Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among sexual minority adults by study sampling strategies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), e1–e12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottes T. S., Ferlatte O., Gesink D. (2015). Suicide and HIV as leading causes of death among gay and bisexual men: A comparison of estimated mortality and published research. Critical Public Health, 25, 513–526. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2014.946887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. (2016, July 21). “I’m petrified for my children”: Will racism and guns lead to America’s ruin? NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/07/21/486688683/im-petrified-for-my-children-will-racism-and-guns-lead-to-americas-ruin

- Kanuha V. K. (2000). “Being”; Native versus “going native”: Conducting social work research as an insider. Social Work, 45, 439–447. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.5.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsman G. W., Gentile P. (2010). The Canadian war on queers: National security as sexual regulation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein K., Holtby A., Cook K., Travers R. (2015). Complicating the coming out narrative: Becoming oneself in a heterosexist and cissexist world. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 297–326. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.970829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotliar D. M. (2016). Depression narratives in blogs: A collaborative quest for coherence. Qualitative Health Research, 26, 1203–1215. doi: 10.1177/10497323156112715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labov W., Waletzky J. (1997). Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 7, 3–38. doi: 10.4324/9780203777176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald N. (2016, July). Small-town Steinbach fills to bursting with gay pride. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/small-town-steinbach-fills-to-bursting-with-gay-pride/

- McKinley J. (2010, October 4). Suicides put light on pressures of gay teenagers. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/04/us/04suicide.html?_r=0

- Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations; Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. (1991). Rock Hudson’s body. In Fuss D. (Ed.), Inside/out: Lesbian theories, gay theories (pp. 259–288). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Michel K., Dey P., Stadler K., Valach L. (2004). Therapist sensitivity towards emotional life-career issues and the working alliance with suicide attempters. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 8, 203–213. doi: 10.1080/13811110490436792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monette P. (1993). Becoming a man: Half a life story. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. (1997). A narrative approach to health psychology: Background and potential. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(1), 9–20. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis J. E., Cochran S. D., Mays V. M. (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 890–901. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelle R. (2010, October 19). Five hundred attend Vancouver vigil for queer youth suicide. Xtra. Retrieved from http://www.dailyxtra.com/vancouver/news-and-ideas/news/five-hundred-attend-vancouver-vigil-queer-youth-suicide-5865

- Reynolds S. K., Lindenboim N., Comtois K. A., Murray A., Linehan M. M. (2006). Risky assessments: Participant suicidality and distress associated with research assessments in a treatment study of suicidal behavior. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 19–34. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P., Greven P. (2001). Gay lives: Homosexual autobiography from John Addington Symonds to Paul Monette. Gender & History, 13, 417–420. [Google Scholar]

- Rofes E. E. (1983). “I thought people like that killed themselves”: Lesbians, gay men, and suicide. San Francisco: Grey Fox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russo V. (1981). The celluloid closet: Homosexuality in the movies. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Salway T., Gesink D., Ibrahim S., Ferlatte O., Rhodes A. E., Brennan D. J., . . . Trussler T. (2018). Evidence of multiple mediating pathways in associations between constructs of stigma and self-reported suicide attempts in a cross-sectional study of adult gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1145–1161. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1019-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson M. (2016, July 1). Mark Simpson: The “Daddy” of the Metrosexual, the Retrosexual, & spawner of the Spornosexual. Available from http://www.marksimpson.com/

- Wang J., Plöderl M., Häusermann M., Weiss M. G. (2015). Understanding suicide attempts among gay men from their self-perceived causes. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203, 499–506. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E. (1988). The beautiful room is empty. New York: Knopf Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. (1984). The genesis of chronic illness: Narrative re-construction. Sociology of Health & Illness, 6, 175–200. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong N. (2015). Planet Nelson. In Barron C. (Ed.), Stories and stigma. Vancouver: Retrieved from http://cbrc.net/sites/cbrc.net/files/stories_and_stigma_web%202.pdf [Google Scholar]