Abstract

Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) functions as a molecular chaperone in its interaction with clients to influence multiple cellular and physiological processes. However, our current understanding on Hsp90’s relationship with mammalian oocyte maturation is still very limited. Here, we aimed to investigate Hsp90’s effect on pig oocyte meiotic maturation. Endogenous Hsp90α was constantly expressed at both mRNA and protein levels in porcine maturing oocytes. Addition of 2 µM 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), the Hsp90 inhibitor, to in vitro mature cumulus–oocyte complexes (COC) significantly decreased Hsp90α protein level (P < 0.05), delayed germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) (P < 0.05), and impeded the first polar body (PB1) extrusion (P < 0.01) of porcine oocytes. 2 µM 17-AAG treatment during in vitro maturation also decreased the subsequent development competence as indicated by the lower cleavage (P < 0.001) and higher fragmentation (P < 0.001) rates of parthenotes, whereas no effects on the percentage and average cell number of blastocysts were found. Immunodepletion of Hsp90α by antibody microinjection into porcine oocytes at germinal vesicle and metaphase II stages induced similar defects of meiotic maturation and parthenote development, to that resulted from 2 µM inhibitor 17-AAG. For oocytes treated by 2 µM 17-AAG, the cytoplasm and membrane actin levels were weakened (P < 0.01), and the spindle assembly was disturbed (P < 0.05), due to decreased p-ERK1/2 level (P < 0.05). However, the mitochondrial function and early apoptosis were not affected, as demonstrated by rhodamine 123 staining and Annexin V assays. Our findings indicate that Hsp90α can couple with mitogen-activated protein kinase to regulate cytoskeletal structure and orchestrate meiotic maturation of porcine oocytes.

Keywords: Hsp90, 17-AAG, porcine, oocyte, MAPK, meiosis

INTRODUCTION

Oocyte meiosis is a complex process orchestrated by precise and sophisticated molecular programs, in order to produce gametes competent for successful fertilization and subsequent embryo development. Two signaling pathways, the maturation-promoting factor (MPF) complex and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (Mos-MEK-ERK1/2), are of principal roles in meiotic resumption and maturation of mammalian oocytes (Zhang et al., 2011). MPF activity is essential for oocyte meiotic resumption (Adhikari and Liu, 2014) and maintenance of metaphase II (MII) arrest (Oh et al., 2013), while MAPK activity is required for spindle assembly (Petrunewich et al., 2009), and also MII arrest (Gordo et al., 2001; Sha et al., 2017). After germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) during meiosis I, oocyte meiosis resumes, and microtubulin organizes into a bipolar spindle at the central position of oocyte to attach kinetochore of chromosomes. Then, actin microfilaments facilitate the migration and anchor of spindle onto oocyte cortex, and form a contractile ring to promote the extrusion of the first polar body (PB1), and the completion of cytokinesis (Zhang et al., 2017). Following PB1 extrusion, the bipolar spindle is formed again during MII. The correct segregation of chromosomes is ensured by the normal organization and functioning of cytoskeleton, actin, and tubulin, which is vital to oocyte meiosis by avoiding aneuploidy formation (Holubcová et al., 2015). In addition, mitochondrial activity and early apoptosis status could be used as markers to indicate cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes, which is another decisive factor of oocyte quality (Song et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018).

Heat shock proteins (Hsp) are highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed proteins that mainly served as molecular chaperones to maintain appropriate folding and conformation of various client proteins (Schlesinger, 1990; Hartl, 1996). Hsps play pivotal roles during a variety of biological and physiological conditions, and under stress situations (Nardai et al., 2000; Voss et al., 2000; Prodromou, 2017). Hsps are expressed in mouse oocytes, including Hsp27 (Liu et al., 2010), Hsp70 (Manejwala et al., 1991), Hsp90 (Metchat et al., 2009) and Hsp105 (Vitale et al., 2007); however, only Hsp27 (Liu et al., 2010) and Hsp90 (Metchat et al., 2009) were reported to be involved in the meiotic regulation of mouse oocytes. Hsp90 includes two cytosolic isoforms, Hsp90α and Hsp90β, that are highly homologous, and in mouse oocytes Hsp90α expression predominates over Hsp90β (Metchat et al., 2009). Inhibition of Hsp90 in mouse oocytes using 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) caused impairment of meiotic resumption, asymmetrical division and reduced MAPK activity (Metchat et al., 2009). 17-AAG is an Hsp90 specific inhibitor with features of more stability and less toxicity than geldanamycin (Whitesell and Lindquist, 2005; Wagatsuma et al., 2017), which has been widely used in human cancer chemotherapy (Singh et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2017) by inducing apoptosis and mitotic arrest (Zhao et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). However, further investigations still await to reveal the critical role of maternal Hsp90 in oocytes of nonrodent mammalian species.

Here, we investigated the functional role of Hsp90 on porcine oocyte meiotic maturation and subsequent embryo development, by inhibiting Hsp90 using 17-AAG and specific antibody microinjection. Porcine oocytes treated by 17-AAG or microinjection of a specific anti-Hsp90α antibody all had similar defects of impaired meiotic progression. Further analysis revealed that the cytoskeleton organization and MAPK-signaling pathway could be perturbed. In addition, both treatments inhibited the cleavage rate, but increased the fragmentation rate of parthenotes. Thus, Hsp90α plays an important role during the physiological process of porcine oocyte meiosis and early embryo development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All animal materials were used according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. All experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Northeast Agricultural University, China.

Chemicals

17-Allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin was obtained from Abcam (ab141433). Other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise mentioned.

Collection and In Vitro Maturation of Porcine Oocytes

Porcine ovaries obtained from a local slaughterhouse were transported and follicular fluid containing cumulus–oocyte complexes (COC) were collected (Li et al., 2016). COC with at least three layers of cumulus cells surrounded and uniform ooplasm were chosen to in vitro maturate for 24 h or 44 h using the method described previously (Li et al., 2016).

17-AAG Treatment

A stock solution of 17-AAG was diluted in Dimethyl Sulfoxide to 4 mM and stored at −20 °C. For each culture, the stock solution was diluted with the maturation medium to prepare 17-AAG solutions at final concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 µM. In the present study, the initial concentrations of 17-AAG were set by referring previously published study on mouse oocytes (Metchat et al., 2009), and then slightly modified according to the phenotypic effects on porcine oocyte maturation. Finally, one of 17-AAG concentrations that had significant effects on porcine oocyte maturation was selected for subsequent experiments.

Assessment of Nuclear Status, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm), and Oocyte Apoptosis

Assessment of nuclear status and mitochondrial ΔΨm level was performed in live oocytes as previously reported (Li et al., 2016). Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection in live oocytes was performed by referring previous report (Song et al., 2017).

Real-Time qPCR

Eighty denuded oocytes were used to extract total RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74104), and the RNase-free DNase (Qiagen, 79254) treatment was performed to remove genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA synthesis, real-time (RT) PCR detection, and relative abundance calculation of transcripts were performed as previously described (Li et al., 2016). Primers were designed by the Primer-blast and primer sequences were shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Denuded oocytes were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described in the report (Li et al., 2016). Samples were then subsequently incubated with rabbit anti-Hsp90α polyclonal antibody (ABclonal, A0365, 1:50) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (TransGen Biotech, HS111, 1:150). After counterstained with 10 µg/mL Hoechst33342 for 10 min, oocytes were mounted onto glass slides and examined with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Laica, Germany).

To visualize spindle, denuded oocytes were permeabilized for 1 h at 39 °C in a pH 6.7 microtubulin stabilizing solution (Simerly et al., 1993). Then, oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and blocked in 2% BSA for 1 h, and then incubated with mouse anti-â-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, T5293, 1:150) overnight at 4 °C, and subsequently with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Sigma, F0257, 1:100) for 1 h at RT. Fixation, permeabilization, and blockage for denuded oocytes to detect actin fluorescence were performed as mentioned above, and 2.5 µg/mL FITC–labeled Phalloidin (Sigma, P5282) was used for incubation at RT for 1 h.

Western Blot

A total of 100 (for Hsp90α) or 200 (for phosphorylated CDK1 [p-CDK1] and p-ERK1/2) denuded live oocytes were collected and western blot procedures were performed as in our previous report (Song et al., 2017). Skimmed milk of 0.5% was used to dilute polyclonal rabbit anti-Hsp90α antibody at 1:2000. Polyclonal rabbit anti-p-CDK1 (T161) (ABclonal, AP0014) and anti-p-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204) (ABclonal, AP0472) antibodies were diluted using 0.5% BSA in PBS at 1:1000. Mouse anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:1000; Transgen Biotech, HC101) was used to re-probe membranes as internal control.

Antibody Microinjection and Parthenogenetic Activation

Rabbit anti-Hsp90α antibody and rabbit IgG (ABclonal, AC005) were microinjected into porcine GV and MII oocytes according to a previously described procedure (Huan et al., 2015). MII oocytes were activated and in vitro cultured as reported method (Li et al., 2016). The cleavage and blastocyst rates were recorded at 48 h and 168 h post activation. The fragmented embryos were categorized into three types by referring the standards previously reported (Antczak and Van Blerkom, 1999). Blastocysts at day 7 were stained by 10 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 to count the total number of cell nuclei.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and SAS9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). After arcsine transformation, the percentages of oocyte nuclei stages, GVBD, PB1, embryo cleavage, and blastocyst were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test (SPSS19). One-way ANOVA was also used to analyze the data of cell number per blastocyst and protein levels detected by western blots (SPSS19). Difference between two groups was analyzed by the independent-sample t-test (SPSS19). Differences in gene expression detected by RT-qPCR were analyzed using the linear mixed model procedure (SAS9.1). Significant differences at P < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels were indicated.

RESULTS

Endogenous Hsp90α Constantly Expressed in Maturing Porcine Oocytes

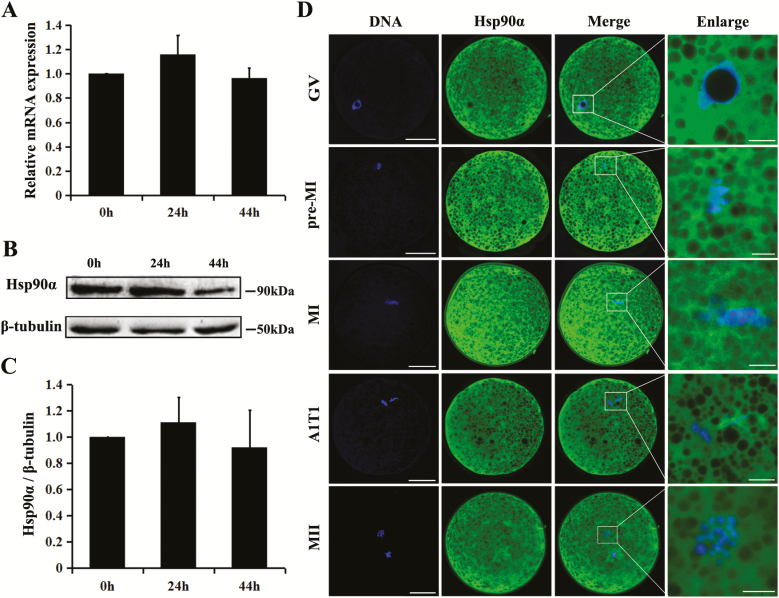

To determine the endogenous level of Hsp90α during meiotic maturation, porcine oocytes were collected at 0, 24, and 44 h of in vitro maturation (IVM), time points corresponding to GV, GVBD, and MII stages for most oocytes, respectively (Song et al., 2017). Real-time PCR analysis showed that during pig oocyte maturation, Hsp90α is constantly expressed (Fig. 1A), and western blots validated the existence of its protein (Fig. 1B and C). Subcellular localization examined by immunostaining identified Hsp90α to be present in both cytoplasm and nuclei areas, except for the nucleolus region of GV oocytes (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Expression and subcellular localization of Hsp90α in maturing porcine oocytes. (A) RT-qPCR results showed Hsp90α mRNA expressed in maturing porcine oocytes and its level did not change significantly among different stages (0 h, 24 h, and 44 h of IVM corresponding to GV, GVBD, and MII stages). (B, C) Western blots showed Hsp90α protein was expressed and its level did not significantly change in porcine oocytes undergoing meiosis. (D) Subcellular localization of Hsp90α via immunofluorescent staining. Green, Hsp90α; blue, chromatin. GV, germinal vesicle; Pre-MI, pre metaphase I; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II. Scale bar, 50 µm in the left three columns; 10 µm in the right column.

Hsp90α Deficiency Impairs Nuclear Maturation

Porcine COC were treated with specific Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG at three concentrations (1, 2, and 4 µM). After IVM for 24 h, we found that the cumulus cell expansion was inhibited by 17-AAG treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A, upper panel). In addition, GVBD rates were decreased for oocytes treated by 17-AAG at 1 µM (84.8% of control vs. 65.7%; P < 0.05), 2 µM (67.4%; P < 0.05), and 4 µM (63.4%; P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 2B). However, no differences existed between the 17-AAG treatment groups.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of Hsp90α by 17-AAG and antibody binding impaired porcine oocyte nuclear maturation. (A) Cumulus expansion was inhibited by adding 17-AAG into the maturation media (1 µM, 2 µM, and 4µM) to culture porcine COC for 24 h. Cumulus-free oocytes were visualized to be with first polar bodies (arrows) after adding 17-AAG (1 µM, 2 µM, and 4 µM) to mature porcine COC for 44 h. (B, C) GVBD rates (24 h) and PB1 rates (44 h) of oocytes derived from COC treated by 17-AAG at different concentration (1 µM, 2 µM, and 4 µM). (D) PB1 rate of GV oocytes denuded of cumulus (CDOs) treated by 2 µM 17-AAG in maturation medium for 44 h. (E, F) Western blots on Hsp90α protein level in oocytes derived from COC treated by 2 µM 17-AAG for 24 h and 44 h during IVM. (G, H) Microinjection of Hsp90α antibody into cytoplasm of porcine GV oocytes confirmed that immuno-inhibition of Hsp90α significantly decreased GVBD rate (24 h) and PB1 rate (44 h). (I, J) p-CDK1 (T161) levels in oocytes derived from COC treated by 2 µM 17-AAG for 24 h and 44 h during IVM. Scale bar, 200 µm. *Significant difference at P < 0.05 level, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. COC = cumulus–oocyte complexes.

For oocytes treated by 17-AAG and then IVM for 44 h, the rates of PB1 extrusion were less in 1 µM (72.8% of control vs. 48.3%; P < 0.05), 2 µM (40.7%; P < 0.01), and 4 µM (23.5%; P < 0.001) treatment groups (Fig. 2A, lower panel; Fig. 2C). Specifically, 4 µM 17-AAG treatment decreased PB1 rate to an even lower level as compared to the other two treatment groups (1 µM and 2 µM; P < 0.05; Fig. 2C), through greatly increasing the rates of oocytes arresting at MI stages (41.3% vs. 13.1% of the control; P < 0.05) and with greater incidences of chromatin abnormality (24.1% vs. 6.7% of the control; P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2). Considering the results of GVBD and PB1 rates as described above, 2 µM 17-AAG was chosen for subsequent experiments. Furthermore, when treating denuded oocytes with 2 µM 17-AAG, the PB1 rate was also less, when compared to the control group (42.8% vs. 61.7% of control; P < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). Thus, inhibition of Hsp90 by 17-AAG impairs the nuclear maturation of porcine oocytes.

Because 17-AAG could inhibit both Hsp90α and Hsp90β, we then further clarified whether 17-AAG mostly acts on Hsp90α to affect porcine oocyte maturation. Firstly, western blots detected that Hsp90α protein level in porcine oocytes was reduced by 2 µM 17-AAG treatment of COC, after IVM for 24 h (0.70 vs. 1.00 of the control; P < 0.05) and 44 h (0.78 vs. 1.00 of the control; P < 0.05; Fig. 2E and F). Secondly, we microinjected specific anti-Hsp90α antibody into porcine GV oocytes denuded of cumulus cells, followed by co-culture with cumulus cells and IVM for 24 h or 44 h. The antibody microinjection system has been previously validated in our lab (data not shown). Specificity of the anti-Hsp90α antibody was verified by western blots, which showed that it recognized only the Hsp90α protein in GV oocytes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Immunodepletion of Hsp90α decreased GVBD rate (61.0% vs. 84.4% of the control; vs. 84.5% of the IgG; P < 0.05; Fig. 2G), as well as PB1 rate (42.8% vs. 76.1% of the control; vs. 74.0% of the IgG; P < 0.001) as compared to the control and IgG groups (Fig. 2H), respectively. The PB1 rate was decreased because of the significant increasing rates of oocytes arresting at MI stages (22.4% vs. 14.2% of the control; vs. 13.9% of the IgG; P < 0.05) and with chromatin abnormality (17.9% vs. 4.3% of the control; P < 0.05; Supplementary Table S3). Similar results obtained from 17-AAG treatment and immunodepletion of Hsp90α suggested that 17-AAG’s effects on porcine oocyte maturation exerted mainly through the inhibition on Hsp90α. Furthermore, the level of p-CDK1 (T161) was assayed by western blots, and 2 µM 17-AAG treatment had no effect on the p-CDK1(T161) level in oocytes collected at 24 h and 44 h of IVM, respectively (P > 0.05; Fig. 2I and J).

Hsp90α and Cytoplasmic Maturation

To know the relationship between Hsp90α and cytoplasm quality, we examined the mitochondrial ΔΨm and early apoptosis of live oocytes after 17-AAG treatment for 44 h. We found that 2 µM 17-AAG treatment elevated the relative RH123 fluorescence level, as compared to the control group (1.25 vs. 1.00; P < 0.001; Fig. 3A and B). However, percentage of oocytes with positive signals of early apoptosis was not changed (18.5% vs.13.7% of the control; P > 0.05; Fig. 3C and D), although slightly increased by 4.8%.

Figure 3.

Effects of Hsp90α inhibition by 17-AAG on mitochondrial membrane potential and early apoptosis of porcine oocytes. (A) Representative fluorescence images taken from porcine oocytes stained with RH123. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) The graphs to present the relative RH123 fluorescence intensity in oocytes. (C) Representative fluorescence images taken from porcine oocytes stained with Annexin V. Scale bar, 100 µm in the left and middle columns; 50 µm in the right column. (D) The graphs to show percentages of apoptosis positive oocytes. ***Significant difference at P < 0.001 level.

Hsp90α Inhibition Disrupts Cytoskeleton Assembly

Because in mice, 17-AAG inhibits Hsp90α and disturbs MAPK activity (Metchat et al., 2009), we further tested whether Hsp90α affects the nuclear maturation of porcine oocytes via cytoskeleton assembly, by examining actin filament distribution and spindle assembly of live porcine oocytes after IVM for 44 h. Actin distribution of oocytes was also disturbed by 2 µM 17-AAG treatment and decreased the relative fluorescence intensity both on membrane (0.59 vs. 1.00 of control; P < 0.01) and in cytoplasm (0.66 vs. 1.00 of control; P < 0.01; Fig. 4A and B). Observation of the spindle morphology showed that the percentage of oocytes with normal spindle morphology was lower in the 2 µM 17-AAG treatment group as compared to the control group (28.3% vs. 61.7%; P < 0.05; Fig. 4C and D). Considering that the MAPK-signaling cascade is the key molecular pathway in regulating microtubule organization in oocytes, we examined the p-MAPK level. Western blots showed that p-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204) was reduced, after exposure to 2 µM 17-AAG for 24 h and 44 h (P < 0.05) during IVM, as compared to the control groups (Fig. 4E and F). Thus, deficiency of Hsp90α disturbed actin distribution and spindle organization of porcine oocytes.

Figure 4.

Suppression of Hsp90α disrupts cytoskeleton assembly of porcine oocytes. (A) Representative fluorescence images of porcine oocytes to show actin organization (green). Scale bar, 50 µm in the middle column; 10 µm in the right and left columns. (B) Quantitative analysis of relative actin fluorescence intensity from cytoplasm and membrane of oocytes. (C) Representative fluorescence images of porcine oocytes showing spindle (green) and chromosome morphology (red). MII oocytes from the control group displayed bipolar-shaped spindles and well-aligned chromosomes on the metaphase equator (a), whereas chromosome misalignment and spindle defects were frequently observed in 2 µM 17-AAG treatment group, which can be classified into four different types (b–e). (a) The normal bipolar-shaped spindle. (b) The monopolar spindle. (c) Spindle losing bipolar. (d) The weakened spindle. (e) The disturbed spindle. Scale bar, 10 µm. (D) Percentages of oocytes with normal spindle organization. (E, F) Western blots of p-ERK1/2 and β-tubulin in oocytes collected at 24 h and 44 h of IVM from the control and 2 µM 17-AAG–treated COC. *Significant difference at P < 0.05 level and **P < 0.01. Abbreviation: COC = cumulus–oocyte complexes.

Hsp90α Inhibition Induces Fragmentation of Parthenotes

We assessed the effects of Hsp90α inhibition during IVM on the subsequent developmental capacity of mature oocytes following parthenogenetic activation. The cleavage rate of parthenotes in the 2 µM 17-AAG treatment group was lower than that of the 1 µM 17-AAG treatment (70.7% vs. 81.4%; P < 0.01) and the control groups (70.7% vs. 84.2%; P < 0.001), owing to the greater fragmentation rate (20.8% vs. 9.8% of 1 µM; vs. 8.1% of the control; P < 0.001; Fig. 5A and B). Further analysis found that fragmented embryos (48 h) could be categorized into three different types, 69.3% of type I, 13.7 % of type II, and 17.0% of type III, indicating that Hsp90 inhibition could cause slight degree of embryo fragmentation (Supplementary Fig. S2A and B). Parthenotes from 2 µM 17-AAG–treated group were isolated at 48 h post activation into two different groups, nonfragmented and fragmented, and cultured separately till day 7. We found that blastocyst rate in the fragmented group was lower as compared to the nonfragmented group (38.1% vs. 53.9%; P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S2C), and the control group (containing both fragmented and nonfragmented parthenotes) (38.1% vs. 58.6%; P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. S2C). However, the cell number per blastocyst showed no difference between the nonfragmented and fragmented groups (Supplementary Fig. S2D). Moreover, after comparing the normal control group and 17-AAG (1 µM and 2 µM) treated groups (mixed nonfragmented and fragmented parthenotes), no differences for blastocyst rates and cell numbers per blastocyst existed among these three groups (P > 0.05, Fig. 5A–C).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of Hsp90α by 17-AAG and antibody binding induces fragmentation of parthenotes. (A) Morphology of cleaved parthenotes and blastocysts from mature oocytes after 17-AAG treatment for 44 h during IVM. (B) Cleavage, fragmentation, and blastocyst percentages of parthenotes from mature oocytes after 17-AAG treatment for 44 h during IVM. (C) Cell number per blastocyst derived from 17-AAG–treated mature oocytes. (D) Morphology of cleaved parthenotes and blastocysts from mature oocytes after anti-Hsp90α antibody microinjection. (E) Cleavage, fragmentation, and blastocyst percentages of parthenotes from mature oocytes after anti-Hsp90α antibody microinjection. (F) Cell number per blastocyst derived from anti-Hsp90α antibody microinjected mature oocytes. Scale bar, 100 µm. *Significant difference at P < 0.05 level, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Similar to 2 µM 17-AAG treatment, immunodepletion of Hsp90α also decreased the cleavage rate, as compared to the IgG (64.7% vs. 84.4%; P < 0.05) and control groups (64.7% vs. 87.5%; P < 0.05), and increased the fragmentation rate as compared to the IgG (26.0% vs. 6.1%; P < 0.01) and control groups (26.0% vs. 7.0% of control; P < 0.01) (Fig. 5D and E). Moreover, blastocyst rates and cell numbers per blastocyst were unchanged, either (P > 0.05; Fig. 5D–F). Therefore, deficiency of Hsp90α induced the fragmentation of parthenotes and caused the low cleavage rate.

DISCUSSION

Hsp90 is a widely expressed endogenous molecular chaperone that influences the proper folding, maturation, and function of client proteins, which are involved in diverse signal transduction pathways (Shapiro and Cowen, 2010; O’Meara et al., 2017; Pennisi et al., 2017). As a result, Hsp90 plays an important regulatory role in multiple physiological and pathological processes, including a variety of cancer types (Chatterjee and Burns, 2017). However, due to high molecular similarity between Hsp90α and Hsp90β, it is not easy to distinguish them from each other in many studies (Calvert et al., 2003; Deng et al., 2017). Evidences from mouse studies support that these two isoforms are regulated by different mechanisms (Voss et al., 2000; Metchat et al., 2009).

Hsp90α was concentrated in the cytoplasm of fully grown oocytes in mouse ovary sections, but Hsp90β in granulosa cells (Metchat et al., 2009). While in another report, Hsp90 was shown to localize on plasma membrane of the major mouse mature oocytes, and in the region opposite to the chromatin pole of some eggs (Calvert et al., 2003). In the present study, we showed that maternal Hsp90α is constantly expressed during porcine oocyte maturation at both mRNA and protein levels. Hsp90α protein was localized in both oocyte cytoplasm and nuclei areas, but without any signal in the nucleolus region of GV oocytes, and no signal enriched in any other stained region, either. Therefore, these different findings could be due to the difference of species, developmental stages, and types of samples used.

Hsp90 is a promising anti-cancer drug target, and its selective inhibitor 17-AAG has potential to be used in anticancer therapy (Soo et al., 2008; Chatterjee and Burns, 2017). 17-AAG treatment of canine osteosarcoma cells for 48 h increased Hsp90 mRNA level in one cell line, but decreased Hsp90 mRNA level in another (Massimini et al., 2017). In the present study, we showed that 17-AAG treatment of porcine COC during IVM induced the significant decrease of Hsp90α protein level in oocytes collected at 24 h and 44 h, suggesting that 17-AAG could disturb Hsp90α function by interfering with its protein expression. Hsp90’s function in meiotic maturation has been previously reported in Caenorhabditis elegans, Xenopus laevis, and mouse oocytes (Fisher et al., 2000; Inoue et al., 2006; Metchat et al., 2009). In mice, 17-AAG treatment delays GVBD, or arrests oocytes at GV stage for more than 6 h delay (Metchat et al., 2009). Our results also showed that 17-AAG treatment significantly decreased GVBD rates of porcine oocytes in vitro matured for 24 h, and anti-Hsp90α antibody injection showed a similar effect. Therefore, Hsp90α is vital to the meiotic resumption of both mouse and porcine oocytes.

Furthermore, we found no changes for the p-CDK1 (T161) level, an Hsp90 client and the key kinase to control GVBD, after 17-AAG treatment of porcine oocytes for 24 h. This is different from the findings in mouse that CDK1 level was markedly reduced after culture with 17-AAG for 12 h (Metchat et al., 2009). However, we did find the significant decrease of the MAPK activity in porcine oocytes after 17-AAG treatment for 24 h. Intra-oocyte MAPK activity has been shown to regulate GVBD in pigs (Inoue et al., 1998; Li et al., 2008). In Xenopus oocytes, Hsp90 is required to activate and phosphorylate Mos, and then subsequently induce MAPK activation and GVBD (Fisher et al., 2000). Thus, in porcine oocytes, Hsp90 might couple with the MAPK-signaling pathway to regulate meiotic resumption.

We observed the significantly decreased percentages of PB1 oocytes after 17-AAG treatment of maturing porcine COC or DO for 44 h, or after anti-Hsp90α antibody microinjection into GV stage oocytes, through increasing the incidence of MI arrest and nuclear abnormality. Cytoskeleton (actin and spindle) abnormality in oocytes with less Hsp90α activity could be one reason for the failure of PB1 extrusion, possibly through interfering with the formation and migration of bipolar spindle in porcine oocytes. The reduced MAPK activity might be another reason for the lower PB1 percentage of porcine oocytes lacking full Hsp90α activity, since MAPK cascade has been proven to regulate spindle assembly (Petrunewich et al., 2009) and MII arrest (Gordo et al., 2001; Sha et al., 2017). Nevertheless, in contrast to mouse oocyte (Metchat et al., 2009), 17-AAG treatment did not induce the defective asymmetrical division in pig oocytes as in the present study. One explanation is that during mouse and porcine oocyte meiosis, centrosomal composition and spindle organization are regulated by different mechanisms (Li et al., 2016).

Inhibition of maternal Hsp90α by 17-AAG and immunodepletion significantly increased the fragmentation rate of parthenotes but had no effect on porcine embryo developmental potential to blastocyst stage. Firstly, 17-AAG treatment during IVM could partially increase the percentage of oocytes with early apoptosis, though not statistically significant, which might be one possible reason for the higher incidence of embryo fragmentation. Supportive evidences have shown that Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG could induce apoptosis in hepatic stellate cells (Myung et al., 2009) and canine osteosarcoma cells (Fisher et al., 2000). Additionally, previous studies reported a direct link between apoptotic processes and early embryo fragmentation (Jurisicova et al., 1996; Jurisicova and Acton, 2004). Secondly, early embryo fragmentation was shown to correlate with oocyte aneuploidy (Stensen et al., 2015), and cytoskeletal disorder was proven to be one reason for oocyte aneuploidy (Zhang et al., 2017). Abnormality of spindle assembly and actin distribution in 17-AAG–treated porcine oocytes could plausibly result in the fragmentation of early embryos. Thirdly, reduced MAPK activity in aged pig oocyte was shown to be associated with defects in embryo fragmentation (Ma et al., 2005). Lastly, the degree of fragmentation determines the developmental competence of embryos, such as blastomere number, blastomere size, and nuclei number (Steer et al., 1992; Antczak and Van Blerkom, 1999). We found that 17-AAG–induced embryo fragmentation was categorized to be from the slight-to-moderate degree (Mateusen et al., 2005), which might not affect the embryo competency to develop to the blastocyst stage.

Taken together, our findings showed that endogenous Hsp90α was constantly expressed in porcine oocytes during in vitro maturation. Inhibition of Hsp90α in maturing porcine oocytes impeded the process of GVBD and PB1 extrusion, disturbed filamentous-actin and meiotic spindle organization, decreased p-MAPK activity, and induced the fragmentation of parthenotes derived from Hsp90α-deficient oocytes. Our results suggest that maternal Hsp90α affects the meiotic maturation of porcine oocytes and subsequent embryo development, via coupling with the MAPK-signaling pathway to regulate cytoskeletal structure.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Animal Science online.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Footnotes

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31472098) and the Start-up grant from Northeast Agricultural University.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adhikari D. and Liu K.. 2014. The regulation of maturation promoting factor during prophase I arrest and meiotic entry in mammalian oocytes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 382:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antczak M. and Van Blerkom J.. 1999. Temporal and spatial aspects of fragmentation in early human embryos: possible effects on developmental competence and association with the differential elimination of regulatory proteins from polarized domains. Hum. Reprod. 14:429–447. doi:10.1093/humrep/14.2.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert M. E., Digilio L. C., Herr J. C., and Coonrod S. A.. 2003. Oolemmal proteomics–identification of highly abundant heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones in the mature mouse egg and their localization on the plasma membrane. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1:27. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S., and Burns T. F.. 2017. Targeting heat shock proteins in cancer: a promising therapeutic approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S. L., Sun T. C., Yu K., Wang Z. P., Zhang B. L., Zhang Y., Wang X. X., Lian Z. X., and Liu Y. X.. 2017. Melatonin reduces oxidative damage and upregulates heat shock protein 90 expression in cryopreserved human semen. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 113:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D. L., Mandart E., and Dorée M.. 2000. Hsp90 is required for c-Mos activation and biphasic MAP kinase activation in Xenopus oocytes. Embo J. 19:1516–1524. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordo A. C., He C. L., Smith S., and Fissore R. A.. 2001. Mitogen activated protein kinase plays a significant role in metaphase II arrest, spindle morphology, and maintenance of maturation promoting factor activity in bovine oocytes. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 59:106–114. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U. 1996. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holubcová Z., Blayney M., Elder K., and Schuh M.. 2015. Human oocytes. Error-prone chromosome-mediated spindle assembly favors chromosome segregation defects in human oocytes. Science. 348:1143–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huan Y., Xie B., Liu S., Kong Q., and Liu Z.. 2015. A novel role for DNA methyltransferase 1 in regulating oocyte cytoplasmic maturation in pigs. Plos One. 10:e0127512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Hirata K., Kuwana Y., Fujita M., Miwa J., Roy R., and Yamaguchi Y.. 2006. Cell cycle control by daf-21/Hsp90 at the first meiotic prophase/metaphase boundary during oogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Growth Differ. 48:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00841.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Naito K., Nakayama T., and Sato E.. 1998. Mitogen-activated protein kinase translocates into the germinal vesicle and induces germinal vesicle breakdown in porcine oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 58:130–136. doi:10.1095/biolreprod58.1.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurisicova A., and Acton B. M.. 2004. Deadly decisions: the role of genes regulating programmed cell death in human preimplantation embryo development. Reproduction. 128:281–291. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurisicova A., Varmuza S., and Casper R. F.. 1996. Programmed cell death and human embryo fragmentation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2:93–98. doi:10.1093/molehr/2.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Ai J. S., Xu B. Z., Xiong B., Yin S., Lin S. L., Hou Y., Chen D. Y., Schatten H., and Sun Q. Y.. 2008. Testosterone potentially triggers meiotic resumption by activation of intra-oocyte SRC and MAPK in porcine oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 79:897–905. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wang Y. K., Song Z. Q., Du Z. Q., and Yang C. X.. 2016. Dimethyl sulfoxide perturbs cell cycle progression and spindle organization in porcine meiotic oocytes. PLoS One. 11:e0158074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. J., Ma X., Cai L. B., Cui Y. G., and Liu J. Y.. 2010. Downregulation of both gene expression and activity of Hsp27 improved maturation of mouse oocyte in vitro. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Zhang D., Hou Y., Li Y. H., Sun Q. Y., Sun X. F., and Wang W. H.. 2005. Reduced expression of MAD2, BCL2, and MAP kinase activity in pig oocytes after in vitro aging are associated with defects in sister chromatid segregation during meiosis II and embryo fragmentation after activation. Biol. Reprod. 72:373–383. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manejwala F. M., Logan C. Y., and Schultz R. M.. 1991. Regulation of Hsp70 mRNA levels during oocyte maturation and zygotic gene activation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 144:301–308. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(91)90423-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massimini M., Palmieri C., De Maria R., Romanucci M., Malatesta D., De Martinis M., Maniscalco L., Ciccarelli A., Ginaldi L., Buracco P., et al. 2017. 17-AAG and apoptosis, autophagy, and mitophagy in canine osteosarcoma cell lines. Vet. Pathol. 54:405–412. doi: 10.1177/0300985816681409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateusen B., Van Soom A., Maes D. G., Donnay I., Duchateau L., and Lequarre A. S.. 2005. Porcine embryo development and fragmentation and their relation to apoptotic markers: a cinematographic and confocal laser scanning microscopic study. Reproduction. 129:443–452. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metchat A., Akerfelt M., Bierkamp C., Delsinne V., Sistonen L., Alexandre H., and Christians E. S.. 2009. Mammalian heat shock factor 1 is essential for oocyte meiosis and directly regulates Hsp90alpha expression. J. Biol. Chem. 284:9521–9528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808819200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung S. J., Yoon J. H., Kim B. H., Lee J. H., Jung E. U., and Lee H. S.. 2009. Heat shock protein 90 inhibitor induces apoptosis and attenuates activation of hepatic stellate cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330:276–282. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.151860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardai G., Sass B., Eber J., Orosz G., and Csermely P.. 2000. Reactive cysteines of the 90-kDa heat shock protein, Hsp90. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 384:59–67. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. S., Susor A., Schindler K., Schultz R. M., and Conti M.. 2013. Cdc25A activity is required for the metaphase II arrest in mouse oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 126(Pt 5):1081–1085. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara T. R., Robbins N., and Cowen L. E.. 2017. The Hsp90 chaperone network modulates Candida virulence traits. Trends Microbiol. 25:809–819. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi R., Antoccia A., Leone S., Ascenzi P., and di Masi A.. 2017. Hsp90α regulates ATM and NBN functions in sensing and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Febs J. 284:2378–2395. doi: 10.1111/febs.14145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrunewich M. A., Trimarchi J. R., Hanlan A. K., Hammer M. A., and Baltz J. M.. 2009. Second meiotic spindle integrity requires MEK/MAP kinase activity in mouse eggs. J. Reprod. Dev. 55:30–38. doi:10.1262/jrd.20096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C. 2017. Regulatory mechanisms of Hsp90. Biochem. Mol. Biol. J. 3:2. doi: 10.21767/2471-8084.100030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M. J. 1990. Heat shock proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 265:12111–12114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Q. Q., Dai X. X., Dang Y., Tang F., Liu J., Zhang Y. L., and Fan H. Y.. 2017. A MAPK cascade couples maternal mRNA translation and degradation to meiotic cell cycle progression in mouse oocytes. Development. 144:452–463. doi: 10.1242/dev.144410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R. S. and Cowen L.. 2010. Coupling temperature sensing and development: Hsp90 regulates morphogenetic signalling in Candida albicans. Virulence. 1:45–48. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.1.10320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly C. R., Hecht N. B., Goldberg E., and Schatten G.. 1993. Tracing the incorporation of the sperm tail in the mouse zygote and early embryo using an anti-testicular alpha-tubulin antibody. Dev. Biol. 158:536–548. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Singh A., Sand J. M., Bauer S. J., Hafeez B. B., Meske L., and Verma A. K.. 2015. Topically applied Hsp90 inhibitor 17AAG inhibits UVR-induced cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135:1098–1107. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z. Q., Li X., Wang Y. K., Du Z. Q., and Yang C. X.. 2017. DMBA acts on cumulus cells to desynchronize nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of pig oocytes. Sci. Rep. 7:1687. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01870-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo E. T., Yip G. W., Lwin Z. M., Kumar S. D., and Bay B. H.. 2008. Heat shock proteins as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. In Vivo. 22:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer C. V., Mills C. L., Tan S. L., Campbell S., and Edwards R. G.. 1992. The cumulative embryo score: a predictive embryo scoring technique to select the optimal number of embryos to transfer in an in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer programme. Hum. Reprod. 7:117–119. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensen M. H., Tanbo T. G., Storeng R., Åbyholm T., and Fedorcsak P.. 2015. Fragmentation of human cleavage-stage embryos is related to the progression through meiotic and mitotic cell cycles. Fertil. Steril. 103:374–81.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale A. M., Calvert M. E., Mallavarapu M., Yurttas P., Perlin J., Herr J., and Coonrod S.. 2007. Proteomic profiling of murine oocyte maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 74:608–616. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss A. K., Thomas T., and Gruss P.. 2000. Mice lacking HSP90beta fail to develop a placental labyrinth. Development. 127:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma A., Takayama Y., Hoshino T., Shiozuka M., Yamada S., Matsuda R., and Mabuchi K.. 2017. Pharmacological targeting of HSP90 with 17-AAG induces apoptosis of myogenic cells through activation of the intrinsic pathway. Mol. Cell Biochem. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-3250-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H., Valbuena J. R., Barbhuiya M. A., Stein S., Kunkel H., García P., Bizama C., Riquelme I., Espinoza J. A., Kurtz S. E., et al. 2017. Small molecule inhibitor screening identified HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG as potential therapeutic agent for gallbladder cancer. Oncotarget. 8:26169–26184. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell L. and Lindquist S. L.. 2005. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 5:761–772. doi: 10.1038/nrc1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhu Q., Chen D., Shen Z., Wang W., Ning G., and Zhu Y.. 2015. The HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG exhibits potent antitumor activity for pheochromocytoma in a xenograft model. Tumour Biol. 36:5103–5108. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3162-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. X., Park W. J., Sun S. C., Xu Y. N., Li Y. H., Cui X. S., and Kim N. H.. 2011. Regulation of maternal gene expression by MEK/MAPK and MPF signaling in porcine oocytes during in vitro meiotic maturation. J. Reprod. Dev. 57:49–56. doi:10.1262/jrd.10-087H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang Q. C., Liu J., Xiong B., Cui X. S., Kim N. H., and Sun S. C.. 2017. The small GTPase CDC42 regulates actin dynamics during porcine oocyte maturation. J. Reprod. Dev. 63:505–510. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2017-034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. M., Wang N., Hao H. S., Li C. Y., Zhao Y. H., Yan C. L., Wang H. Y., Du W. H., Wang D., Liu Y., Pang Y. W., and Zhu H. B.. 2018. Melatonin improves the fertilization capacity and developmental ability of bovine oocytes by regulating cytoplasmic maturation events. J. Pineal. Res. 64: e12445. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang J., Xiao L., Xu Q., Zhao E., Zheng X., Zheng H., Zhao S., and Ding S.. 2016. Effects of 17-AAG on the cell cycle and apoptosis of H446 cells and the associated mechanisms. Mol. Med. Rep. 14:1067–1074. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Wang J., Xiao L., Xu Q., Zhao E., Zheng X., Zheng H., Zhao S., and Ding S.. 2017. Effects of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin on the induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HCT-116 cells. Oncol. Lett. 14:2177–2185. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.