Abstract

Of the three RAS oncoproteins, only HRAS is delocalized and inactivated by farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTI), an approach yet to be exploited clinically. In this study, we treat mice bearing Hras-driven poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers (Tpo-Cre/HrasG12V/p53flox/flox) with the FTI tipifarnib. Treatment caused sustained tumor regression and increased survival; however, early and late resistance was observed. Adaptive reactivation of RAS-MAPK signaling was abrogated in vitro by selective RTK (i.e. EGFR, FGFR) inhibitors, but responses were ineffective in vivo, whereas combination of tipifarnib with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 improved outcomes. A subset of tumor-bearing mice treated with tipifarnib developed acquired resistance. Whole-exome sequencing of resistant tumors identified a Nf1 nonsense mutation and an activating mutation in Gnas at high allelic frequency, supporting the on-target effects of the drug. Cell lines modified with these genetic lesions recapitulated tipifarnib resistance in vivo. This study demonstrates the feasibility of targeting Ras membrane association in cancers in vivo and predicts combination therapies that confer additional benefit.

Keywords: Thyroid cancer, HRAS, MEK inhibitor, NF1, GNAS, tipifarnib, farnesyltransferase inhibitor, resistance

Introduction

Development of compounds that inhibit oncogenic RAS remains a major unfulfilled challenge. As opposed to activating kinase mutations, which enable small molecule targeting of their enzymatic activity, RAS mutants lose GTPase function, resulting in reduced GTP hydrolysis and activation of downstream signaling. Pharmacologic targeting of GDP/GTP exchange and inhibition of Ras-effector interactions have not proven so far to be effective strategies (1). Recently, a series of KRAS-G12C specific inhibitors that bind covalently to the mutant cysteine residue have shown promise and are in preclinical development (2).

Although oncogenic HRAS mutations are comparatively less frequent than those of K and NRAS, they are significantly represented in follicular thyroid cell-derived and in medullary thyroid carcinomas, as well as in head and neck and bladder cancers (3–8). HRAS is the only RAS oncoprotein that can be pharmacologically inhibited through membrane delocalization by farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs). This is because upon farnesyltransferase inhibition, N- and K- but not HRAS are geranyl-geranylated, and hence remain membrane anchored and functional (9). Accordingly, FTIs are preferentially active against HRAS as compared to NRAS or KRAS-mutant cancer cell lines (9–11). FTIs were originally developed to target RAS but were ineffective in clinical trials (12, 13). However, these studies did not attempt to enroll patients with HRAS-driven cancers, and hence the efficacy of targeting the association of RAS with membranes has not been formally tested in patients, or in genetically accurate mouse models of Hras-driven cancer.

The FTI lonafarnib has been previously shown to preferentially inhibit growth of HRAS-mutant cancer cell lines, and to essentially eliminate HrasG12V-driven papillomas in mice (10). We developed a mouse model of HrasG12V-driven cancer that phenocopies poorly differentiated or anaplastic thyroid cancers, and used this to test the efficacy, adaptive and acquired responses to the FTI tipifarnib. The drug evoked strong anti-tumor responses, but both early and delayed resistance ensued. Adaptive resistance to tipifarnib was associated with upstream activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), primarily EGFR and FGFR1. Combination with a MEK inhibitor, but not with the RTK inhibitors erlotinib or ponatinib, markedly improved in vivo responses to tipifarnib, consistent with heterogeneity of the adaptive inputs upstream of Ras. Individual cases of acquired resistance to tipifarnib were driven by Nf1 loss, resulting in reactivation of Ras signaling, and by activating Gnas mutations, which induced a transcriptional program of re-differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Genetically Engineered Mice and Mouse Tumor Cell Lines

All animal protocols were approved by the MSKCC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To generate triple transgenic (Hras;p53) mice we crossed animals harboring Tpo-Cre (14), Trp53flox (15), and FR-HrasG12V (16) alleles (mixed background containing 129, swiss black, FVB/n and C57bl6). Thyroid ultrasound (VisualSonics Vevo 770 In Vivo High-Resolution Micro-Imagin System, VisualSonics Inc.) was performed after isoflurane anesthesia and hair removal. The neck was imaged from above the larynx through the thoracic inlet with image capture every 250 microns and subsequent volume determination. Tumor-bearing animals were defined as having an identifiable tumor extending outside the normal thyroid bed. Total thyroid volume was used to assess the thyroid since the boundaries of the tumors were often difficult to clearly delineate by ultrasound and as they could also involve both thyroid lobes.

Cell Culture and Reagents

To generate mouse tumor cell lines, tumors were dissected, minced in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 10ml of digestion MEM (Minimum Essential Media) medium containing collagenase type I (112U/ml; Worthington; #CLS-1), dispase (1.2U/ml; Gibco; #17105-041), penicillin (50U/ml) and streptomycin (50µg/ml). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes with vigorous shaking and then passed through a 10ml pipette followed by an additional 60 minutes of shaking. Cells were spun down and resuspended in Coon’s F12 with penicillin/streptomycin/L-glutamine (P/S/G; Gemini; #400-110) and 0.5% bovine brain extract for two weeks and then switched to Coon’s F12 with P/S/G in 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Lines were passaged at least 5 times prior to use in experiments.

Hth83 and C643 human cancer cell lines were obtained from Nils-Erik Heldin, Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden. Prior to experiments they were authenticated using short tandem repeat and single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis and tested negative for mycoplasma. They were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and P/S/G. HEK293FT and Platinum-E (PlatE) cell lines were grown in DMEM-HG (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) and DMEM, respectively and all cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

All drugs used in vivo were administered by gavage. Tipifarnib (Kura Oncology) and erlotinib (Selleckchem) were dissolved in 20% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (CTD, Inc), which also served as vehicle. AZD6244 (AstraZeneca) was dissolved in 0.5% methycellulose and 0.1% Tween80. Ponatinib (AK Scientific, Inc.) was dissolved in 25mM citric acid buffer. All tumors were collected 2 hours after last dose of drug. Tumor-bearing mice were identified by ultrasound, then stratified by sex and tumor size/thyroid volume and then randomized to treatment groups.

Histology, Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

After CO2 anesthesia, thyroid tumors were dissected from surrounding tissues and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 hours at 4°C. The specimens were washed twice with PBS and placed into 70% ethanol. Paraffin embedding, sectioning, deparaffinization and staining were carried out by the MSKCC Molecular Cytology Core. Sections were immunostained with Iba-1 (Wako; 019-1974, 0.5 mcg/ml), pERK (Cell Signaling #4370; 1.0 mcg/ml), Ki67 (Abcam; Ab16667, 2.5 mcg/ml), pAKT473 (Cell Signaling #4060; 1.0 mcg/ml). Quantitation of immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed using color threshold analysis. Slides were scanned with Pannoramic Flash 250 (3DHistech, Budapest, Hungary) and regions of interest manually drawn using Pannoramic Viewer and exported as tiled tiff images. The images were analyzed using FIJI/ImageJ. A color deconvolution algorithm was used to separate 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and hematoxylin signals. A set threshold value was used to segment positive DAB signal as well as tissue area. Percent of DAB signal over tissue area for each image was measured.

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining was performed using a Discovery XT processor (Ventana Medical Systems). Tumors were processed as above. Fixation of cell lines was performed on chamber slides exposed to 4%PFA for 30 minutes and washed with PBS. Slides were incubated first with anti-vimentin (Progen; # GP53; 0.1ug/ml) for 5 hours, followed by 60 minutes incubation with biotinylated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Vector labs; # BA-7000; 1:200). The detection was performed with Streptavidin-HRP D (DABMap kit, Ventana Medical Systems), followed by incubation with Tyramide Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen; # T20922) prepared according to manufacturer instruction with predetermined dilutions. Slides were then incubated with anti-E-cadherin (Cell Signaling; #3195, 2.5 ug/ml) using the same protocol as vimentin except for an alternative secondary antibody (biotinylated goat anti-rabbit, Vector Labs; # PK6101, 1:200 dilution). After staining, slides were counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma Aldrich; # D9542; 5 ug/ml) for 10 minutes and mounted in Mowiol reagent.

Human Tumor and Cell Line Expression Arrays

Thyroid cancer cell lines underwent RNA extraction and gene expression was measured with Affymetrix U133 2.0 arrays. We also mined publically available human expression array data with the same platform from normal thyroid and thyroid tumors (17) (GSE76039). Genotyping for mutant RAS or BRAF status was performed by targeted exome sequencing as previously described (17). Expression array data was normalized in Partek genomic Suite 6.6. The data was sorted for expression of RTKs (18) and RTK ligands.

Ligands and proliferation assays

For proliferation assays, 30,000 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. The day after plating (day 0), drugs/ligands were added. Media/drugs/ligands were replaced on day 3, and cells harvested on day 6 by trypsinization and counted with a Vi-Cell series Cell Viability Analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Ligand concentrations are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Immunoblots and RAS-GTP assays

Cells were rinsed with cold PBS and lysed in Mg2+ lysis buffer (containing 125 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.5, 750 mmol NaCl, 5% Igepal CA-630, 50 mmol MgCl2, 5 mmol EDTA, and 10% glycerol; Millipore #20-168) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete Mini, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set I and II, Sigma). Tumors were homogenized in 1× Lysis/Binding/Wash Buffer (containing 25 mmol Tris-HCl, 150 mmol NaCl, 1% NP-40, 5% Glycerol, and 5 mmol MgCl2; Thermo Fisher Scientific #1862301) also supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were briefly sonicated to disrupt the tissue before clearing by centrifugation. The protein concentrations of the lysates were measured using the BCA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5). Western blots were performed as previously described (19). Membranes were incubated with secondary goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (1:5000 or 1:7500; Santa Cruz; sc-2004) or goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated antibody (1:5000 or 1:10000; Santa Cruz; sc-2031) for 1h at room temperature. Blots were developed by chemiluminescence in Amersham ECL Prime (GE Healthcare Biosciences) or SuperSignal West Pico (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Immobilon HRP (Millipore) reagents per manufacturer’s instructions. RAS-GTP was measured using the Active Ras Pull-Down and Detection Kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific (#16117) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, followed by immunoblotting to detect GTP-bound levels of total RAS or RAS isoforms.

RNA Interference

For small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of KRAS and NRAS, cells were transfected with 50nM of either the targeting or control siRNA (Qiagen) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen; #13778-100), following the manufacturer’s protocol (Supplementary Table 2). After transfection, cells were incubated with DMSO or Tipifarnib for 72 hours.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR and Expression Arrays

Total mRNA was extracted from cells and snap-frozen thyroid tissue with PrepEase Kit (USB Corporation). The amount and purity of RNA were determined by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific). RNA expression from Tpo-Cre, Tpo-Cre/HrasG12V and Hras;p53 PDTC/ATC was measured on Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays (Deposited in the GEO repository: GSE112476. Data were analyzed using Partek Genomic Suites 6.6. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Super Script III First Strand Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-Time PCR was performed by using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. For the analysis of expression we used the ΔΔCt method, using β-actin as the housekeeping gene.

Vectors, mutagenesis and cell transfection

Short hairpins for human EGFR and NF1 were cloned into pMSCV-miRE vector and pLKO vector (MSKCC RNAi Core Facility), respectively. The Gnas plasmids were purchased from GeneCopoeia (EX-Mm27105-Lv205 for mouse). GNAS201 refers to the canonical GNAS sequence, GαS2. Gnas mutants were generated on the GαS1 cDNA, since expression of this transcript was the highest among those expressed from the Gnas complex locus in our models (NM_001077510). The GNASR201S position in human and mouse GαS2 corresponds to the following substitutions: GNASR187S in GαS1 and GNASR940S in Xlas-1 in both species. GNASR160C in GαS2 corresponds to GNASR146S in GαS1. To be consistent with the reported annotation in the literature, we refer throughout the manuscript to GnasR201S and GnasR160C mutations. The mutant Gnas cDNAs (GnasR201S and GnasR160C) were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. We introduced substitutions at the 201 and 160 sites using 50ng of plasmid, Acuprime PFX (Invitrogen; 12344-040), using a PCR protocol. Forward and reverse primers used to introduce the mutations are shown in Supplementary Table 4. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm that the desired mutations were introduced. For Gnas, transient transfection of HEK293FT cells was performed by using the Lenti-Pac HIV Expression Packaging Kit (Genecopoeia; HPK-LvTR-20), 24h after cells were seeded (5×105/dish) in 60mm dishes. For EGFR and NF1 hairpins, transient transfection of PlatE cells was performed using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Promega); 24h later cells were seeded (2×106/dish) in 60mm dishes, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For infections, cells were incubated with infectious particles twice in the presence of 8ug/ml of polybrene (Santa Cruz; sc-134220). The medium was replaced 24h after the second infection with fresh medium containing 1.5–2.5 µg/ml puromycin (Millipore; 540411). Efficiency of knockdown was verified by immunoblotting.

To generate a myristoylated HRAS, NIH3T3 cells were transduced with either HRASG12V (NM_005346.3; Genecopoeia; CS-B0109-Lv205-01) or myristoylated HRASG12V (MGQSLT or ATGGGTCAATCTCTTACA; Genecopoeia; CS-B0109-Lv205-02) in a pReceiver-Lv205 plasmid. HEK239FT cells were transfected with plasmid, using the Lenti-Pac HIV Expression Packaging Kit, 48h after cells were seeded (1.5×106/dish) in 100mm dishes. Lentivirus were collected 48h post transfection and NIH3T3 cells were transduced in the presence of polybrene. After 72h post-transduction, 1.5 µg/ml puromycin was added to the medium and selected cells were used in proliferation assays.

CRISPR/Cas9 Nf1 gene editing and selection

Single-guide RNAs targeting the NF1 binding domain in exon 39 were designed using the CRISPR design software program (http://crispr.mit.edu/) and ligated into BsmBl-linearized LentiCRISPR plasmid (20) [gift from Feng Zhang via Addgene; #49535]. Hras;p53 PDTC cells (5×105 cells per 60mm dish) were plated overnight, and transfected with 1µg of LentiCRISPR plasmid using FuGene 6, selected under 2.5µg/ml of puromycin for 48h and plated in a 150mm dish (500 cells). Single-cell colonies were expanded for DNA and protein extraction, and proliferation assays. PCR primers spanning potential target sites of deletion were designed (F 5’-AAAGAATCGACCGTGCTTTG-3’, R 5’-ACAGGGTACCACAGACAAAAA-3’). Mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Mouse Genomics

Fresh frozen mouse tumors were laser capture microdissected (LCM) in the Pathology Core Lab, Precision Pathology and Biospecimen Center (PPBC) of MSKCC using Leica LMD6. Tissue sections of 8–10 µm were placed on PEN membrane slides (Applied Biosystems) and stained with H&E. Multiple serial sections of tissue were used to maximize yields. Collected cells were pooled together for DNA extraction. Array CGH and whole exome sequencing were performed with Agilent 415K Mouse CGH arrays and SureSelect All Exon capture kit, respectively. We developed a novel approach to aCGH-specific normalization to deal with a specific feature of aCGH microarray data since these profiles are subject to artifacts related to genomic regional labeling efficiency. These artifacts may result from regional variation in DNA degradation, fragmentation, methylation or other features affecting sample DNA differently than reference DNA. Because the artifacts are regionally distributed, they can appear as regional increases and decreases in probe log2 ratios, mimicking copy number aberrations (CNA). Circular binary segmentation and other approaches cannot distinguish such artifacts, and they are typically segmented as altered regions. We have incorporated genomic artifact models based on %GC over 50Kb, 2Kb and 200bp windows for quantitation of artifact during quality assurance and for removal using loess during normalization. Segmentation files were analyzed using IGV 2.3.82.

Samples were prepared for whole exome sequencing according to the manufacturer instructions. PCR amplification of the libraries was carried out for 6 cycles in the pre-capture step and for 8 cycles post capture. Samples were barcoded and run on a Hiseq 2500/4000 in a 100bp/100bp paired end run, using the TruSeq SBS Kit v3 (Illumina). The average coverage was 300× for the tumor samples and 116× for the normal samples. The data processing pipeline for detecting variants in Illumina HiSeq data is as follows: First the FASTQ files are processed to remove any adapter sequences at the end of the reads using cutadapt (v1.6). The files are then mapped using the BWA mapper (bwa mem v0.7.12). After mapping, the SAM files are sorted and read group tags are added using the PICARD tools. After sorting in coordinate order the BAM's are processed with PICARD MarkDuplicates. The marked BAM files are then processed using the GATK toolkit (v 3.2) according to best practices for tumor-normal pairs. They are first realigned using the InDel realigner and then the base quality values are recalibrated with the BaseQRecalibrator. Somatic variants are then called in the processed BAMs using muTect (v1.1.7). A more complete description and a full listing of the code used in this pipeline are available at: https://github.com/soccin/BIC-variants_pipeline.

Xenografts/allografts

Cells at 70% confluency were trypsinized, resuspended in medium, and injected into the right flank of nude mice (5×106 cells per mouse). Treatment by gavage (see above for drug regimens) commenced when xenografts/allografts reached measurable volumes (≈100–300 mm3). Xenograft volume was measured with calipers 2–3 times per week for 3 weeks and tumors collected 2h after last dosing. Tumors were placed immediately in either liquid N2 or 4% PFA. For RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), RNA extraction of frozen tissue was performed by the MSKCC Integrative Genomics Operation. After ribogreen quantification and quality control of Agilent BioAnalyzer, 500ng of total RNA underwent polyA selection and Truseq library preparation according to instruction provided by Illumina (TruSeq™ RNA Sample Prep Kit v2), with 6 cycles of PCR. Samples were barcoded and run on a Hiseq 2500 in a 50bp/50bp Paired end run, using the TruSeq SBS Kit v3 (Illumina). An average of 58 million paired reads was generated per sample. At most the ribosomal reads represented 0.1% and the percent of mRNA bases was closed to 66% on average. RNA-seq data was analyzed using GSEA (broadinstitute.org/gsea).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism 7.0a. Two-tailed t-tests were used for data with an assumed Gaussian distribution whereas Mann-Whitney tests were used as non-parametric tests. Kaplan Meier survival curves were analyzed with a log rank test. Statistical significance was defined as a p<0.05. IC50 values and curves were generated using non-linear regression.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunoblots at a dilution of 1:1000, except where indicated. HRAS (sc-520), NRAS (sc-31; 1:500), KRAS (sc-30; 1:500), FRS2 (sc-8318), CREB (sc-58) and GFP (sc-9996) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; pMEK S217/221 (#9121), tMEK (#9122), pERK (#9101), tERK (#4695), FGFR1 (#9740), pFRS2 (#3864), pAKT (#9271), EGFR (#4267), pEGFR (#3777) and pCREB (#9198) were from Cell Signaling Technology; β-Actin (A2228; 1:10000) and Vinculin (V4139) were from Sigma; and NF1 (A300-140A-M) was from Bethyl Laboratories.

Results

Mice with thyroid-specific inactivation of p53 and knock-in of HrasG12V develop aggressive thyroid cancers

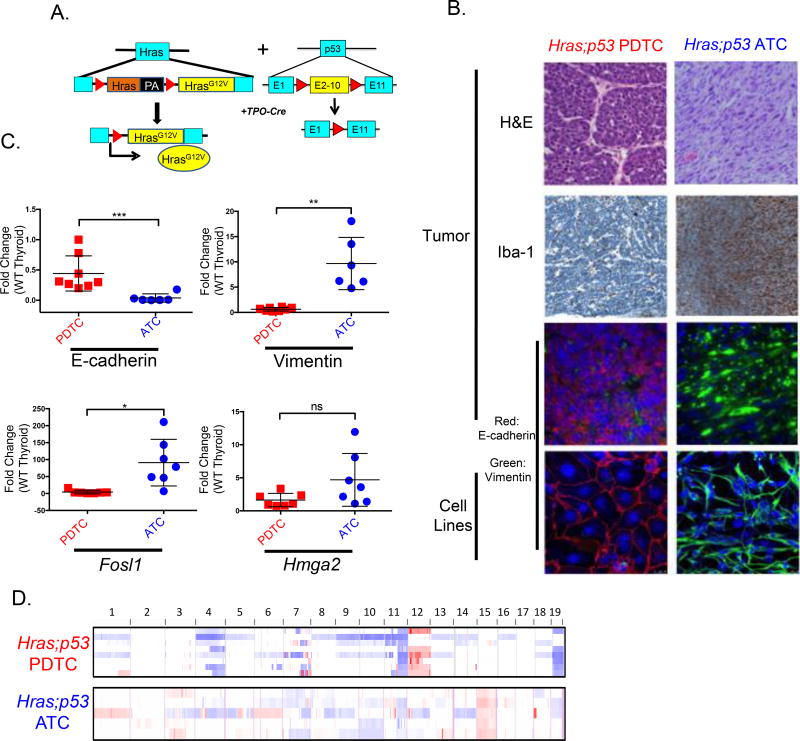

Mutations of TP53 are genomic hallmarks of advanced forms of thyroid cancer (17). To derive a dedifferentiated, Ras-driven thyroid cancer model we developed mice harboring flox-and-replace HrasG12V and floxed p53 alleles (p53f), selectively disrupted in thyrocytes through a Tpo-Cre transgene (Fig. 1A). Tpo-Cre/HrasG12V+/+, Tpo-Cre/HrasG12V+/−, or Tpo-Cre/p53f/f mice failed to generate thyroid tumors, but when combined (Hras;p53) produced aggressive tumors that recapitulated the histological characteristics of human poorly differentiated (PDTCs) or anaplastic thyroid cancers (ATCs). ATCs were characterized by spindle-shaped cells with loss of E-cadherin and increased vimentin expression, whereas PDTCs had focal necrosis and tightly packed groups of E-cadherin positive cuboidal cells (Fig. 1B). We generated cell lines from these two distinct tumor types, and found that they consistently retained their original epithelial/mesenchymal characteristics in vitro (Fig. 1B). Tumor-bearing mice had a 50% mortality by ~ 40 weeks (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Doubling time for ATCs was consistently short (8.8+/−0.97 days), whereas in PDTCs it was more variable (18.1+/−4.8) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Hras;p53 tumors had reduced or absent expression of the thyroid specific genes Nis, Tg, Tpo and Tshr. The thyroid lineage transcription factor Pax8 was also partially suppressed, whereas Nkx2.1 (Ttf1) was not affected (Supplementary Fig. 1C). The expression of the MAPK transcription output markers Fosl1 and Hmga2 (21) tended to be higher in ATCs than PDTCs (Fig. 1C), consistent with findings from their human counterparts (17). Array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) of Hras;p53 PDTCs and ATCs identified distinct copy number alterations between the two phenotypes: PDTCs had copy number gains of chromosome 12, whereas ATCs had gains of chromosome 15. Copy number loss was observed on chromosomes 11 and 19 in both tumor types (Fig. 1D). Expression arrays from matched tumors identified numerous dysregulated genes at these specific chromosomal locations as compared to normal thyroid glands from control animals (Supplementary File 1). Consistent with their human counterparts, Hras;p53 murine ATCs were heavily infiltrated with macrophages, resulting in decreased tumor purity and likely accounting for the attenuated copy number signals (Fig. 1B,1D). Whole exome sequencing of 3 ATCs, 3 PDTCs, and one cell line derived from each histotype confirmed loss of sequence reads in the p53 floxed exons, which was dampened in the ATC tumor, likely because of the extent of the macrophage infiltration, as the ATC cell line showed complete loss of the floxed allele (Supplementary Fig. 1D). There was a trend towards a higher mutation burden in ATCs, although there were no distinguishing patterns of mutations between the two phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 1E; Supplementary Table 5), as is also the case in human tumors (17).

Figure 1. Tpo-Cre/FR-HrasG12V+/+/p53f/f mice develop anaplastic and poorly differentiated thyroid cancers.

A. Scheme of mouse model: Thyroid-specific expression of Cre recombinase driven by Tpo-Cre excises the wild type Hras allele, resulting in endogenous expression of HrasG12V. Exons 2–10 of p53 are floxed to inactivate the allele. B. Representative sections from Hras;p53 ATCs and PDTCs. Top 3 rows: sections of mouse tumors. Bottom row: clonal cell lines derived from each tumor type. Shown are H&E (40×); IHC for the macrophage marker Iba-1 (20×), and immunofluorescence for E-cadherin, vimentin, and nuclear staining with DAPI (20×). Hras;p53 tumor features are retained in the cell lines (40×). C. Real time-PCR of the indicated gene products (performed in triplicate) in Hras;p53 PDTCs and ATCs as compared to wild-type normal thyroid glands (pooled normal samples, n=3) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). D. Array CGH of laser capture microdissected frozen Hras;p53 PDTCs (n=8) and ATCs (n=5). Red: copy number gain; Blue: copy number loss.

Growth inhibition of murine PDTCs and ATCs and HRAS-driven thyroid cancer cell lines is attenuated by adaptive resistance to tipifarnib

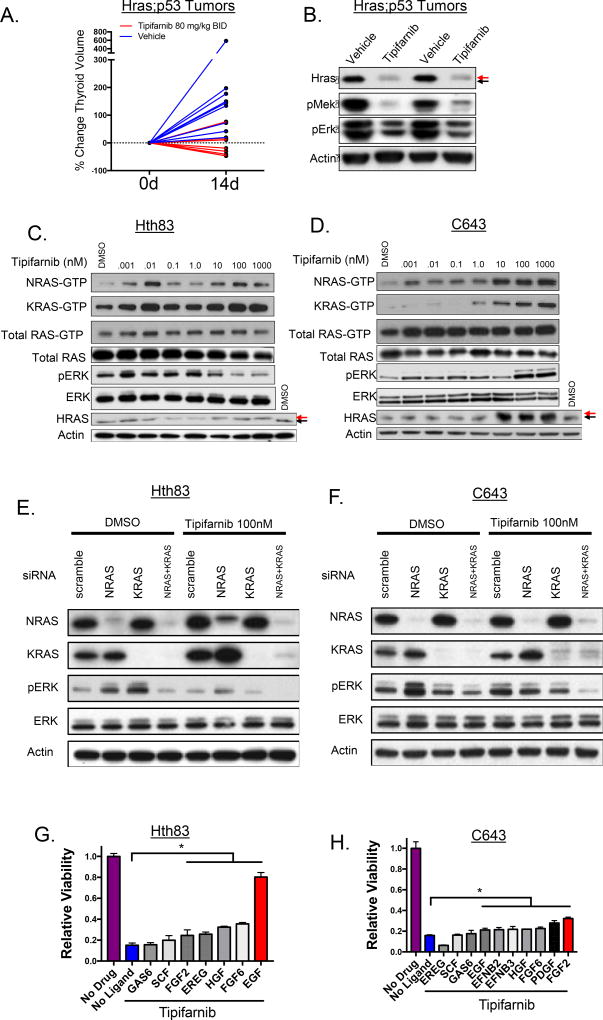

Treatment of tumor-bearing Hras;p53 mice with tipifarnib markedly reduced tumor volume as compared to vehicle-treated controls at 14 days, with modest toxicity manifesting by weight loss (<10% over 2 weeks), although all mice were able to complete the study (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 2A). A subset of mice showed persistent, although dampened, tumor growth. This occurred despite appropriate inhibition of the target, as determined by Hras defarnesylation, which was suggestive of an adaptive response to tipifarnib (Fig. 2B). We reasoned that adaptation to Hras inhibition may have resulted from release of negative feedback inputs upstream of the oncoprotein, and that this would lead to increased GTP loading of wild-type Ras proteins (22). To confirm the specificity of tipifarnib for targeting HRAS, we mass transfected NIH3T3 cells with myristoylated (irreversibly membrane bound) and non-myristoylated-HRASG12V, and observed a shift in tipifarnib IC50 from 21 nM to 79 nM in myristoylated-HRASG12V expressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Next, we treated HRAS-mutant thyroid cancer cell lines C643 and Hth83 with tipifarnib for 12 hours and observed dose-dependent inhibition of ERK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 2C). However, exposure to tipifarnib for 72 hours increased GTP loading of wild-type NRAS and KRAS in the human (Fig. 2C,D) and murine (Supplementary Fig. 2D) HRAS-mutant cell lines. Although this was associated with variable effects on ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2C,D; Supplementary Fig. 2D), we posited that this may blunt the overall efficacy of blocking oncogenic HRAS on downstream signaling. Consistent with this, combined silencing of wild-type NRAS and KRAS inhibited ERK phosphorylation in Hth83 and C643 cells treated with tipifarnib for 72 hours (Fig 2E,F). We next performed phospho-RTK array assays in Hth83 and C643 after exposure to 100 nM tipifarnib for 72 hours to identify possible upstream inputs responsible for activating wild-type RAS. This showed relatively modest increases in phospho-RTKs (Supplementary Fig. 2E). These results are in stark contrast to the adaptive responses of BRAFV600E thyroid cancer cells to RAF kinase inhibitors, which induce an 11-fold increase in phosphorylation of HER3, due in part to constitutive ligand (neuregulin) expression by these cell lines (19). To define optimal conditions that may drive adaptation of the signaling network to tipifarnib, we explored the transcriptional profile of RTKs and RTK ligands in normal human thyroid tissue, well-differentiated and dedifferentiated human thyroid cancer specimens and thyroid cancer cell lines. We derived a rank-order of ligand-RTK expression in the two RAS-mutant cell lines, which was consistent with findings in tumor specimens (Supplementary Fig. 2F). We explored the effects of those top ranked ligands on cell proliferation in the presence and absence of 100nM tipifarnib in Hth83 and C643 cells (Fig. 2G,H). Although GAS6 and its receptor AXL ranked highly in human and murine thyroid cancers, as well as in thyroid cancer cell lines, exposure to GAS6 did not promote tipifarnib resistance. The Hth83 cell line was most sensitive to EGF, which nearly completely abrogated the growth inhibitory effects of tipifarnib (Fig. 2G). EGF induced a more potent activation of pEGFR, wild type RAS-GTP, pAKT, and pMEK in Hth83 cells treated with tipifarnib, which was blocked by the EGFR kinase inhibitor erlotinib, consistent with relief of a negative feedback (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Accordingly, exposure to EGF shifted the tipifarnib dose-response on growth to the right, which was reversed by erlotinib, and by expression of EGFR shRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 3B). By contrast, C643 cells displayed minimal resistance to tipifarnib regardless of ligand exposure, with FGF2 showing some modest effects (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Signaling by FGF2 was augmented in the presence of tipifarnib. Ponatinib, a multikinase inhibitor with activity against FGFR and PDGFR, abrogated the effects of FGF2 on signaling and on cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 2. Adaptive responses to tipifarnib in Hras-mutant thyroid cancers.

A. Tumor bearing Hras;p53 mice were treated with vehicle (n=9) or 80 mg/kg BID tipifarnib (n=6) for 14 days. Thyroid volume was calculated using 3D ultrasound. B. Reduction in pERK and pMEK in Hras;p53 tumor lysates from mice treated with tipifarnib for 72h. Black arrow: farnesylated Hras; red arrow: defarnesylated Hras. C,D. Western blots of human HRAS-mutant thyroid cancer cell lines exposed to increasing concentrations of tipifarnib for 72h. Wild-type RAS-GTP levels increase with greater concentrations of tipifarnib. Arrows show molecular weight shift with HRAS defarnesylation. E,F. Western blot showing a reduction of pERK in tipifarnib-treated C643 and HTH83 cells collected at 72h with knockdown of both wild-type RAS proteins. G. Effect of exposure to individual ligands for 72h on the growth response to 100 nM tipifarnib in Hth83 cells (performed in triplicate). Growth in tipifarnib-treated cells exposed to FGF2, EREG, HGF, FGF6, and EGF was greater than in the absence of ligand (*p<0.05, t-test). H. Effects of ligand exposure on response to tipifarnib in C643 cells (performed in triplicate). Growth in the presence of 100nM tipifarnib was greater after exposure to EGF, EFNB2, EFNB3, HGF, FGF6, PDGF, FGF2 compared to no ligand (*p<0.05, t-test).

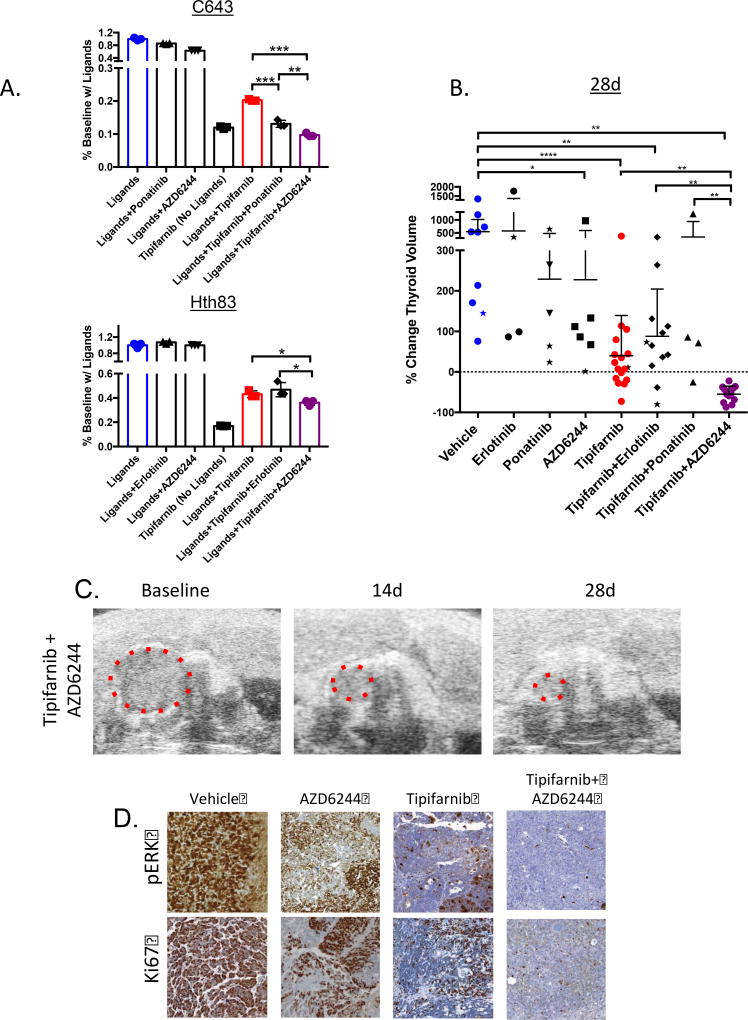

Exposure of Hth83 and C643 cells to a pooled combination of ligands selected based on their ability to induce growth in the presence of tipifarnib (Fig. 2G,H) resulted in partial resistance to the drug. Combination treatment of tipifarnib with ponatinib abrogated pooled ligand-induced growth in C643 cells, whereas erlotinib was ineffective in Hth83 cells. By contrast, treatment with the allosteric MEK inhibitor AZD6244 enhanced sensitivity to the FTI in both cell lines (Fig. 3A), indicating that blocking signaling downstream of RTK activation may be more effective in overcoming the adaptive resistance to tipifarnib when cells are exposed to multiple ligands, which may be a more accurate reflection of the tumor microenvironment. To extend these observations in vivo, we examined RTK and RTK ligand expression in Hras;p53 murine PDTCs and ATCs (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Pdgfra, Pdgfrb and Fgfr1 were highly expressed in both tumor types, whereas Egfr expression was more variable. Treatment of mice with ponatinib or erlotinib did not reduce tumor volumes, and did not improve on the effects of tipifarnib when combined with this drug (Fig. 3B). By contrast, Hras;p53 mice treated with the tipifarnib/AZD6244 combination had significantly greater reduction of tumor volume at 4 weeks as compared to tipifarnib alone (Fig. 3B,C), which was associated with a dramatic reduction in pERK and Ki67 staining (Fig. 3D). These effects were sustained through 8 weeks in a separate cohort of animals (Supplementary Fig 4B).

Figure 3. The MEK inhibitor AZD6244 improves responses to tipifarnib in Hras-mutant tumors and cell lines.

A. Proliferation assays (counted at 6d, performed in triplicate) in Hras-mutant human cell lines in the presence of a pool of RTK ligands (from Fig. 2G,H with *p<0.05) and the indicated drugs (tipifarnib 100nM, erlotinib 25nM, ponatinib 25nM, AZD6244 200nM). Top: C643 cells exposed to FGF2, PDGF, FGF6, HGF, EFNB3, EFNB2, and EGF in 10% serum, (**p<0.01, (***p<0.001, t-test). Bottom: Hth83 cells exposed to EGF, FGF6, HGF, EREG, and FGF2 in 10% serum (*p<0.05, t-test) B. Change in thyroid tumor volume as measured by ultrasound in Hras;p53 mice treated with vehicle (n=9), tipifarnib (80 mg/kg BID, n=17), erlotinib (25 mg/kg BID, n=4), ponatinib (25 mg/kg QD, n=5), AZD6244 (25 mg/kg BID, n=6) or the indicated combinations (tipifarnib+erlotinib: n=12, tipifarnib+ponatinib: n=4, tipifarnib+AZD6244: n=12) at 28 days. Stars indicate mouse tumor measurements at 14 days in mice that did not survive to 28 days. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney test). C. Ultrasound images from representative mouse thyroid tumor treated with tipifarnib and AZD6244. D. Representative sections of Hras;p53 tumors stained for pERK and Ki67 treated with the indicated compounds for 28 days (20×). Tissues were collected 2h after the last dose.

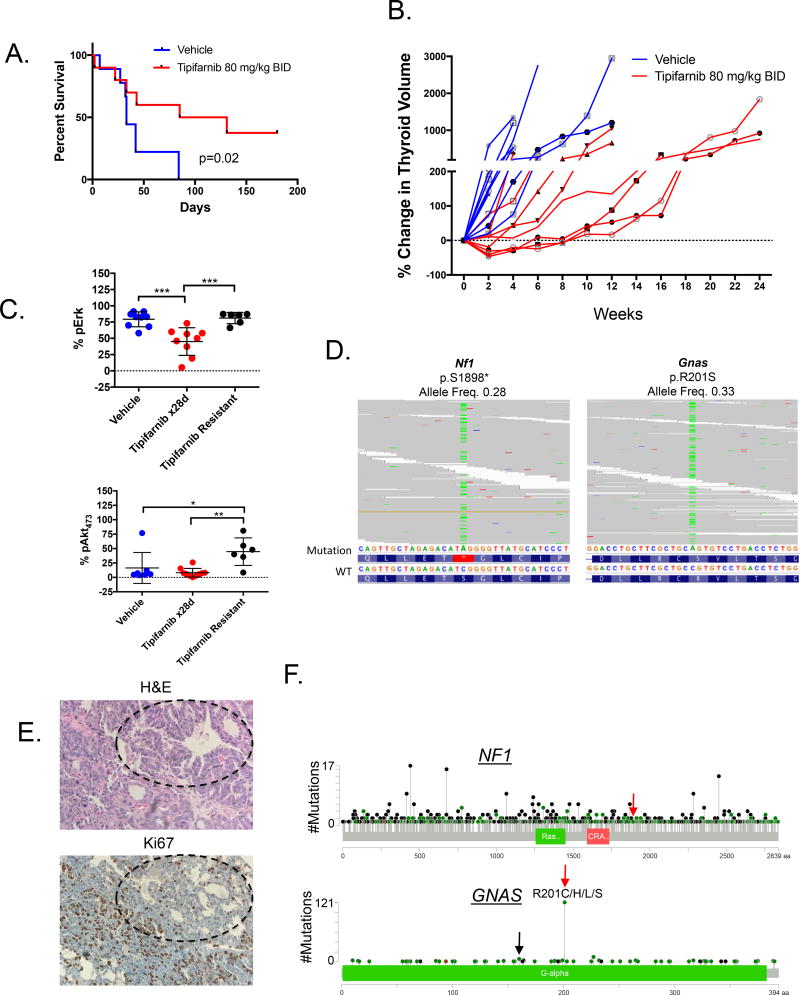

Mechanisms of acquired resistance to tipifarnib

Treatment of tumor-bearing Hras;p53 mice for up to 6 months with tipifarnib prolonged their survival (Fig. 4A). Despite this, all tumors eventually developed resistance to the drug (Fig. 4B), which was associated with reactivation of Ras downstream signaling (Fig. 4C). To explore potential mechanisms of acquired resistance to tipifarnib we initially performed whole exome sequencing of 3 tumors that experienced late growth after an initial response. We found a truncating Nf1 mutation and an activating Gnas mutation (R201S) at high allelic frequencies in two PDTC tumors (Fig. 4D, 4E Supplementary Table 6). These mutations were absent in a set of untreated Hras;p53 ATCs and PDTCs (Supplementary Table 5). Although these mutations were not recurrently seen in other tumors that grew after exposure to tipifarnib (n=9), we explored their functional consequences in greater detail because they pointed to possible on-target effects of the drug on oncogenic Hras.

Figure 4. Nf1 and Gnas mutations in tipifarnib-resistant Hras;p53 tumors.

A. Tipifarnib (n=9) prolongs survival of tumor-bearing Hras;p53 mice compared to vehicle (n=10) (log-rank p=0.02). B. A time course of thyroid volume changes (as measured by ultrasound) in tumor-bearing Hras;p53 mice treated with vehicle (n=10) or tipifarnib 80 mg/kg BID (n=9). C. Increased Erk (top) and S473-Akt (bottom) phosphorylation in vehicle (n=10) and tipifarnib-treated tumors (28 days, n=9) and tipifarnib-resistant tumors (n=6) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney test) as measured by color threshold analysis of IHC-stained tumor sections. D. BAM files from whole exome sequencing of two Hras;p53 PDTCs, one with a truncating Nf1 mutation in exon 39 (left) and one with activating R201S mutation in Gnas (right). E. H&E and Ki67 of the tipifarnib resistant mouse tumor with the GnasR201S mutation (20×). Well-differentiated components with lower Ki67 staining (black circles) are identified in proximity to the poorly differentiated elements. F. Pan-cancer spectrum of NF1 and GNAS mutations in an institutional clinical cohort undergoing targeted exome sequencing with the MSK-IMPACT panel (55). Red arrows indicate amino acid changes observed in resistant Hras;p53 tumors. GNASR201 mutations are the most common. GNASR160 substitutions are also observed in human tumors (black arrow).

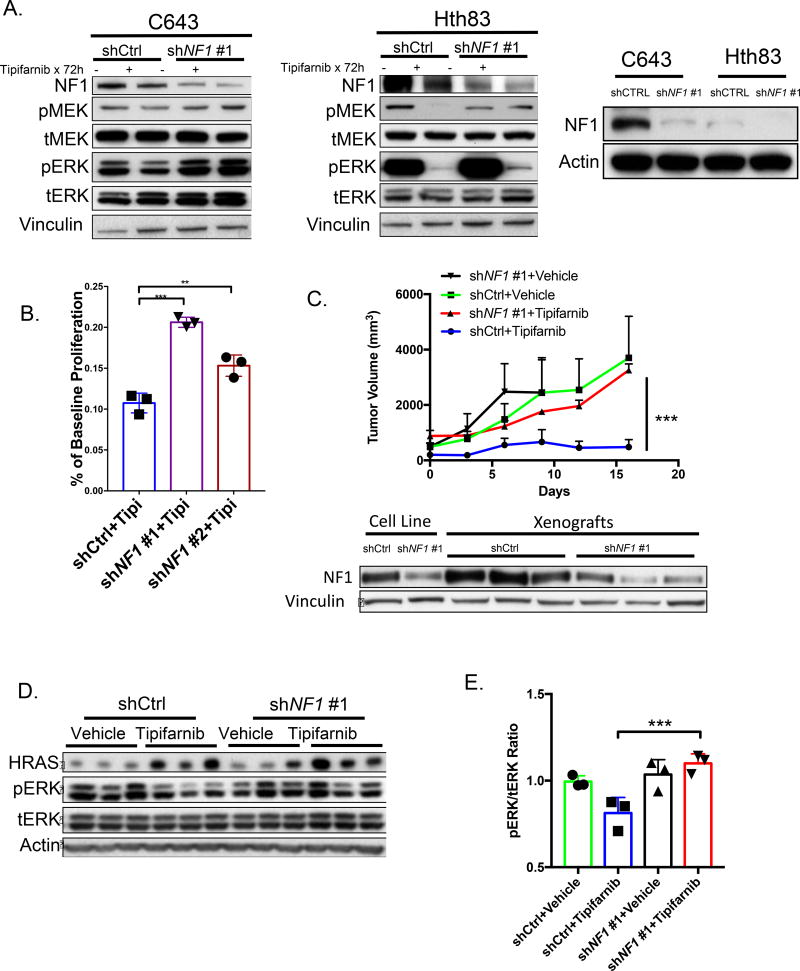

NF1 knockdown partially abrogates the inhibitory effects of tipifarnib on MAPK signaling and induces resistance to the drug

NF1 encodes for a GTPase activating protein and is a negative regulator of RAS (23). The Nf1 mutation predicts for a protein truncation distal to the central GTPase-activating protein-related domain. Of note, NF1 loss-of-function mutations in human cancers occur along the entire gene, as illustrated in an institutional pan-cancer clinical cohort (Fig. 4F).

Knockdown of NF1 in C643 and Hth83 cells dampened the inhibitory effects of tipifarnib on MAPK signaling (Fig. 5A). Hth83 cells are NF1-low, likely explaining the attenuated effects of NF1 knockdown on signaling and growth. Notably, NF1-high C643 cells had a consistently higher IC50 than Hth83 cells when tested across several passages (C643 IC50: 11.9±4.7, Hth83 IC50: 5.1±1.98, n=5, p=0.02). NF1 knockdown evoked tipifarnib resistance in C643 cells in vitro (Fig. 5B) and in vivo (Fig. 5C), and was associated with increased pERK compared to tipifarnib-treated controls (Fig. 5D,E). Since the Nf1 mutation was found in an Hras;p53 mouse PDTC, we also used CRISPR/Cas9 to induce biallelic loss-of-function Nf1 mutations in a murine Hras;p53 PDTC cell line. This eliminated Nf1 protein expression, and resulted in a shift in IC50 to tipifarnib from 4nM to 23nM (Supplementary Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Knockdown of NF1 causes resistance to tipifarnib.

A. Western blot of vehicle or tipifarnib-treated C643 (left) and Hth83 cells (middle) expressing NF1 or control shRNAs. Right panel shows basal expression of NF1 in the two cell lines. B. Six-day proliferation assays of C643 cells expressing the indicated short hairpins in the presence of tipifarnib (100nM), performed in triplicate (*p<0.05, t-test). C. Top: C643 xenografts with NF1 knockdown are resistant to tipifarnib (shNf1 #1 + tipifarnib vs shCTRL+ tipifarnib: ***p<0.001 (n=3 in each group) at 16 days, Mann-Whitney test). Bottom: Western blot of xenografts demonstrate NF1 knockdown in C643 cells expressing NF1-shRNA. D. ERK phosphorylation is increased in tipifarnib-treated C643 xenografts with NF1 knockdown. E. Quantification of Western blot in Fig. 5D (***p<0.001, t-test).

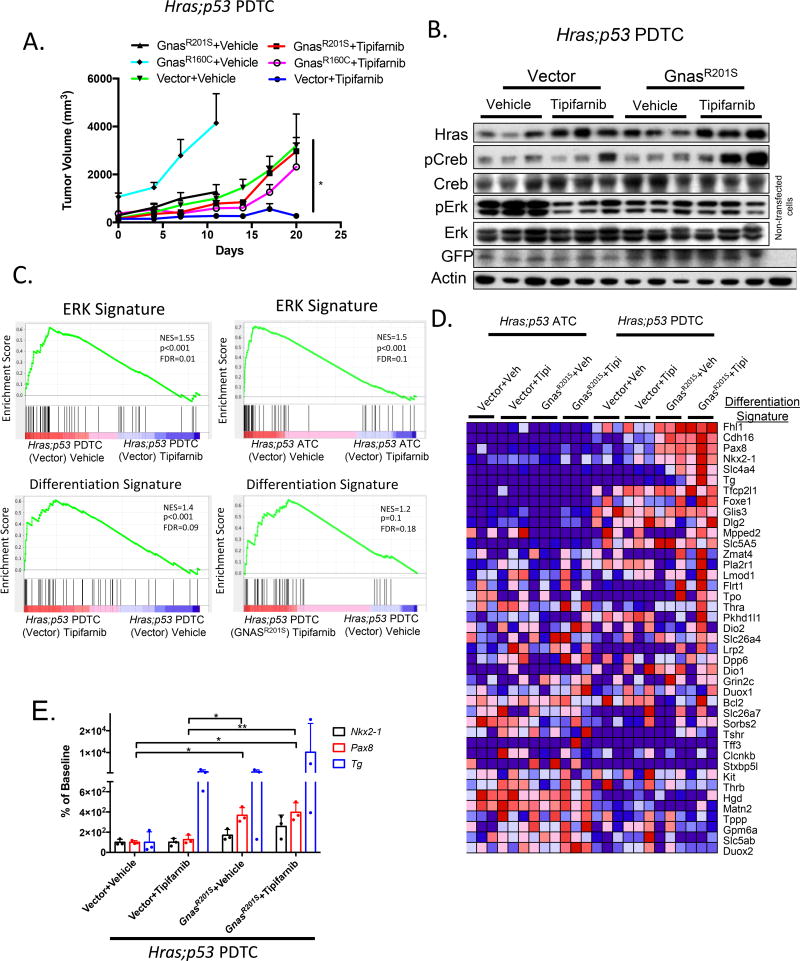

Gnas mutations induce tipifarnib resistance in vivo, and reactivate a thyroid differentiated transcriptional program

Activating GNAS mutations at the R201 position are the most common gain-of-function substitution in human tumors (Fig. 4F), and lie within an exon that is evolutionarily conserved between humans and mice (Supplementary Fig. 6A). The mutant protein encodes for the alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein (Gαs) that activates adenylyl cyclase, which in thyroid cells results in increased expression of thyroid differentiation genes, including those required for thyroid hormone biosynthesis (24) Histology of the Gnas-mutant PDTC demonstrated regions with lower Ki67 staining and features consistent with a well-differentiated phenotype, a finding we did not otherwise encounter in untreated Hras;p53 mutant cancers (Fig. 4E).

The GNAS cluster contains multiple imprinted transcripts, including Gαs and NESP55, preferentially expressed from the maternal allele, and the paternally expressed XLas, A/B and antisense transcripts. We first determined that GαS1 was the predominantly expressed transcript in HRAS-mutant human and murine cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6B), and used the mouse homolog as template for generating gain-of-function GnasR201S (identified in the tipifarnib resistant mouse PDTC) and GnasR160C constructs, the latter because of its common occurrence in human tumors (Fig. 4F). We studied the Gnas mutations in murine cell lines, as the only HRAS-mutant human cell lines are derived from ATCs, and we surmised that some residual potential for redifferentiation might be necessary to observe an effect from the Gnas mutations.

PDTC (E-cadherin positive) allografts derived from Hras;p53 mutant cell lines transduced with either of the Gnas mutants were resistant to tipifarnib (Fig. 6A). Vector-transduced Hras;p53 allografts showed inhibition of pERK in response to tipifarnib. By contrast, and consistent with the known inhibitory effects of cAMP activation on MAPK signaling, baseline pERK was lower in the GnasR201S-transduced allografts, and not further inhibited by tipifarnib. However, there was an increase in pCreb, a protein kinase A substrate, in GnasR201S-transduced but not in vector-transduced allografts treated with tipifarnib, consistent with activation of cAMP-dependent signaling, a pathway which promotes growth and differentiation of normal thyrocytes (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Mutations in Gnas drive resistance to tipifarnib and activate a transcriptional program of thyroid differentiation.

A. Hras;p53 PDTC allografts (in nude mice) transduced with Gnas mutants R160C and R201S are resistant to tipifarnib (80 mg/kg BID) (tipifarnib-treated: GnasR201S vs vector, *p<0.05; GnasR160C vs vector, *p<0.05, Mann-Whitney test, n=5 all conditions). B. Western blot of vehicle or tipifarnib-treated Hras;p53/vector or Hras;p53/GnasR201S allograft lysates (from Fig.6A) show increased pCreb in tipifarnib-treated tumors expressing GnasR201S. The vector contains an IRES-GFP sequence. C. Top: GSEA plots showing significant reduction of a 52 gene ERK signature in vector- -transduced Hras;p53 ATC and PDTC allografts treated with tipifarnib. Bottom: Tipifarnib treatment of Hras;p53 PDTC allografts results in enrichment of thyroid differentiation genes, which is augmented in Hras;p53 tumors transduced with GnasR201S as compared to vehicle-treated vector controls. The Differentiation Signature is based on the Thyroid Differentiation Score identified in the TCGA study of papillary thyroid cancer (29). D. RNA-seq of vehicle or tipifarnib-treated vector- or GnasR201S-transduced Hras;p53 PDTC and ATC allografts shows enrichment of thyroid differentiation genes in response to tipifarnib in Gnas-transduced PDTC allografts. E. Pax8, Nkx2.1, and Tg expression levels measured by real-time PCR. Tg is enhanced in 2/3 Hras;p53 PDTC allografts treated with tipifarnib, confirming the RNA-seq data and consistent with samples with higher Creb phosphorylation (Fig 6B). Pax8 expression was greater in cells transduced with GnasR201S (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, t-test).

By contrast, expression of the Gnas mutants did not significantly dampen the growth inhibitory effects of tipifarnib in Hras;p53 (E-cadherin negative) ATCs (Supplementary Fig. 7A) and failed to induce CREB phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig 7B). RNA sequencing of Hras;p53 PDTC and ATC allografts showed that tipifarnib reduced expression of ERK signature genes in both tumor types (Fig. 6C). However, a transcriptional signature of thyroid differentiation was induced by tipifarnib only in PDTCs, an effect that was further augmented in Hras;p53 PDTCs expressing GnasR201S (Fig. 6C,D,E). Importantly, expression of Nkx2-1 and Pax8, master regulators of thyroid differentiation, was increased in cells transduced with GnasR201S (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

The requirement of RAS association with cellular membranes for signaling is well established (25). This is promoted through post-translational modifications of the RAS C-terminal CAAX motif. The initial and obligate step in this process is catalyzed through farnesyltransferase, which attaches a farnesyl isoprenoid lipid to the cysteine of the CAAX box. This prompted efforts to develop effective FTIs, which were later found to be ineffective against KRAS and NRAS, as these become substrates for geranyl-geranyltransferase 1, allowing them to associate with membranes and remain functional (9). However, HRAS is effectively delocalized by FTIs, disrupting its signaling and biological action (26). The relative rarity of HRAS mutations in cancers raised questions on whether it is a bona fide oncogenic driver and a legitimate therapeutic target (27), despite experimental evidence pointing to distinct transforming potency of mutant RAS isoforms in different cell lineages (28). Several lines of evidence should now dispel these concerns: 1. Mutations of HRAS are mutually exclusive with other driver mutations signaling along the MAPK pathway in thyroid and other malignancies (29). 2. Endogenous expression of HrasG12V drives murine thyroid tumorigenesis in the context of Nf2, Pten or p53 loss (30). 3. As shown here, acquired resistance to Hras delocalization can be mediated by loss of function mutations of Nf1, which when absent de-represses Ras signaling to induce transformation (31).

FTIs can also disrupt other farnesylated proteins, which could contribute to the efficacy and/or toxicity of the drugs. Among these, the two mammalian Rheb isoforms, Rheb1 and Rheb2, have received particular attention, as they are critical components of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt-TSC-mTOR pathway. In its GTP-bound state Rheb activates the rapamycin-sensitive mTOR complex (mTORC1), a step which is inhibited by FTIs (32). Other relevant farnesylated proteins include the centromere-binding proteins CEBP-E and CEBP-F. Upon treatment with FTIs CEBP-E no longer associates with microtubules, which results in accumulation of cells in metaphase (33, 34). However, our current report points to Hras as the key therapeutic target of tipifarnib in the context of tumors harboring Hras mutations. Consistent with results using genetic targeting of oncogenic RAS, treatment with tipifarnib resulted in GTP loading of wild-type RAS, which reactivated downstream signaling (22). Even more telling was the fact that acquired resistance to tipifarnib was associated with a de novo inactivating mutation of Nf1. Although these data point to oncogenic Hras as the primary target of tipifarnib in this setting, we cannot exclude that other farnesylated proteins may have contributed to its effects.

Although tipifarnib induced clear responses and extended survival of mice with Hras-driven thyroid cancers, in most cases the drug stabilized the disease or dampened tumor growth. As mentioned, Hras delocalization was associated with activation of wild-type RAS and adaptive resistance to the drug, which could be overcome in vitro by blocking distinct upstream RTKs driving wild-type RAS activation. As opposed to BRAF-mutant thyroid cancer cells, where activation of the NRG1-HER3/HER2 pathway is primarily responsible for relief of negative feedback in response to RAF or MEK inhibition (19), the RTK responses were relatively modest and heterogeneous in the HRAS context. Accordingly, neither erlotinib nor ponatinib, which showed some activity in vitro, were effective alone or in combination with tipifarnib in vivo. It may be that a combination of upstream inputs drives adaptive responses to the drug in this setting. In contrast, combination of tipifarnib with the MEK inhibitor AZD6244 (selumetinib) was remarkably effective. This is consistent with maintenance of tumor viability via Hras-independent reactivation of MAPK signaling after treatment with the FTI. Newer allosteric MEK inhibitors, such as trametinib, inhibit ERK more potently than selumetinib in RAS-mutant contexts, and may ultimately prove to be preferable in combination with tipifarnib for HRAS-mutant disease (35). Whereas HRAS-mutant thyroid cancers are observed less frequently than BRAF or NRAS, they are present in sufficient numbers that have enabled basket clinical trials with tipifarnib, which are on-going.

Upon treatment with FTIs, Hras accumulates as a cytoplasmic defarnesylated pool. We found that the accumulation of the defarnesylated HRAS varied considerably in tipifarnib-treated Hras-mutant human and mouse models, with some cells exhibiting decreased levels and others higher levels of the protein (25). We currently have no explanation for this variability. Besides farnesylation, HRAS plasma membrane localization requires palmitoylation on two cysteines immediately upstream of the CAAX motif (36). Depalmitoylation at the plasma membrane in turn initiates recycling of HRAS to endomembranes. This pool of defarnesylated mutant HRAS could relocate to the plasma membrane and attenuate effects of FTIs depending on the PK of the drug and its bioavailability, and may also explain the dampened response to the drug in vivo. The cycle of depalmitoylation and repalmitoylation, which regulates HRAS and NRAS subcellular trafficking, can be interrupted by the acyl protein thioesterase 1 (APT1) inhibitor palmostatin B (37). Treatment with this drug randomizes Ras localization to all membranes, and was shown to induce partial phenotypic reversion in oncogenic HRasG12V-transformed fibroblasts (37) and in NrasG12D-transduced hematopoietic cells (38). Conceivably, combination therapy with a farnesyl transferase and an APT1 inhibitor may achieve more profound and sustained Hras delocalization, and if tolerated, improve responses.

Prolonged treatment of Hras-mutant tumors with tipifarnib resulted in emergence of a resistant tumor that harbored a nonsense mutation in Nf1. As would be predicted based on their common mechanism of action, RAS and NF1 are mutually exclusive in most cancers, including those of the thyroid (17, 29). Loss of function of NF1 also confers resistance to other therapies that indirectly target the RAS signaling pathway, including RAF inhibitors in melanoma, and EGFR kinase inhibitors in lung cancer (39–41).

In addition to Nf1 loss, we identified a canonical activating mutation of Gnas in a resistant tumor, which when transduced into HrasG12V mouse thyroid tumor cells generated resistance to tipifarnib. GNAS mutations were first identified in GH-secreting pituitary tumors (42), and subsequently in autonomously functioning thyroid nodules(43), mucin producing IPMNs and appendiceal cancers (44, 45). The GNASR201S mutation reduces GTP hydrolysis of Gαs, and leads to constitutive activation of adenylyl cyclase and generation of cAMP (42). In thyroid cells the cAMP signaling pathway induces cell growth and expression of genes required for thyroid hormone biosynthesis. Accordingly, GnasR201S-transduced Hras;p53 PDTC cells exhibited increased expression of a thyroid differentiation transcriptional program. Treatment with tipifarnib further potentiated cAMP signaling, as measured by phosphorylated Creb, and was associated with greater expression of thyroid-specific iodine metabolism genes.

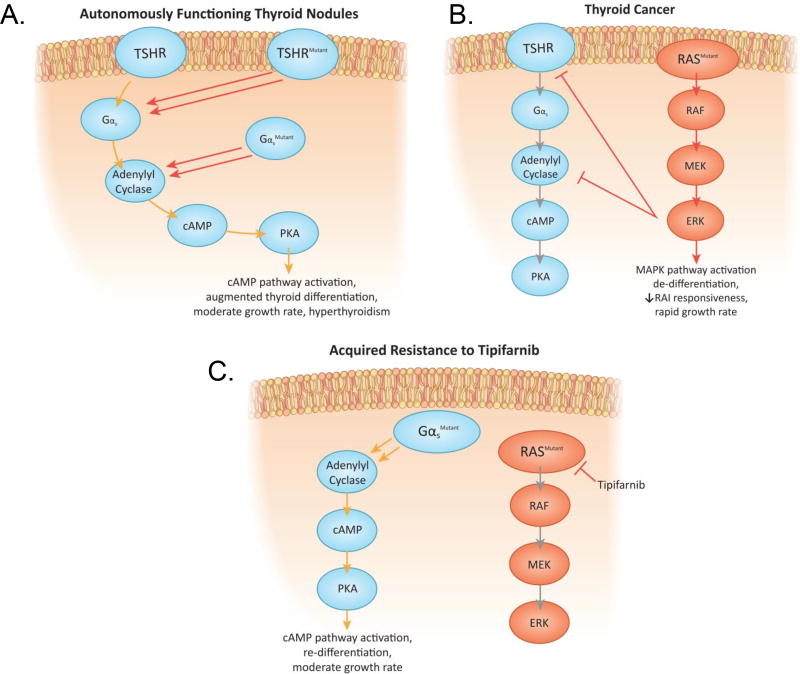

In well differentiated thyroid cancers the transcriptional output of the MAPK pathway is inversely correlated with the expression of genes involved in iodide transport and thyroid hormone biosynthesis, which as mentioned are regulated by cAMP-dependent signaling (29). This reciprocal relationship has been exploited in the clinic, as treatment of BRAF or RAS-mutant thyroid cancers with RAF or MEK inhibitors restores iodide transport, and responsiveness to radioiodine therapy (46–49). The cAMP-protein kinase A pathway suppresses MAPK signaling in many cell types, primarily through inhibition of CRAF (50). Conversely, there is global silencing of thyroid-differentiated function when MAPK is constitutively activated (46, 51) (Figure 7A,B,C). Enforced overexpression of RAS or of a constitutively active RAF protein in thyroid FRTL5 cells decreases the transcriptional activity of Nkx2-1 (TTF-1), a homeodomain-containing transcription factor required for normal thyroid development and expression of thyroid-specific proteins (52, 53). Hence, acquisition of a Gnas mutation in response to tipifarnib inhibition of MAPK signaling restores cAMP control of cell growth, and returns thyroid cells to a more differentiated state. Interestingly, activation of a cAMP-dependent melanocytic signaling network can generate resistance to RAF inhibitors in melanoma cells, suggesting that this may be a common property of cell lineages dependent on cAMP for differentiated function (54). All of these prior situations result from adaptive responses of the signaling network to MAPK pathway inhibitors. The discovery of a gain of function Gnas mutation, which constitutively activates cAMP signaling, in a tipifarnib-resistant tumor is the first demonstration that this mechanism of escape from MAPK blockade can also arise as a result of a somatic mutation.

Figure 7. Acquired resistance to tipifarnib by Gnas activating mutations: Reciprocal relationship between MAPK activation and cAMP signaling in thyroid cancer.

A. Activating mutations of the TSH receptor or GNAS induce growth and differentiated function in autonomously functioning thyroid adenomas. B. Constitutive activation of MAPK by oncogenic RAS inhibits TSH-dependent cAMP signaling at multiple levels (RAI=radioactive iodine) (51). C. Acquisition of a Gnas mutation with long term tipifarnib exposure reactivates cAMP signaling, partially restoring differentiated gene expression and cell growth.

The resistance mutations we found were of interest because of their functional consequences, however it is legitimate to ask why they were not recurrent, as few acquired resistance-mutations were identified in the tumors we studied (we also found a clonal mutation of Arid1b in one additional sample). We believe that the most likely explanation is that these cancers exhibit significant adaptive resistance to the drug, which is best illustrated by the markedly improved and more durable responses to combined tipifarnib-AZD6244 treatment. Thus, tipifarnib alone may not exert sufficient selective pressure for higher frequency acquisition of de novo resistance mutations.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that FTIs specifically target the HRAS oncoprotein and that reactivation of RAS signaling through adaptive responses or through acquired genomic changes can limit their effectiveness. Since clinical trials with tipifarnib are currently accruing for patients with HRAS-mutant malignancies, and efforts are underway to develop compounds targeting other RAS isoforms, these results will help inform the design of subsequent rational combination strategies.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

Tipifarnib effectively inhibits oncogenic HRAS driven tumorigenesis, and abrogating adaptive signaling improves responses. NF1 and GNAS mutations drive acquired resistance to Hras inhibition supporting the on-target effects of the drug.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH P50-CA72012 (JA Fagin), P30-CA008748 (Memorial Sloan Kettering), RO1-CA72597 (JA Fagin), RO1-CA50706 (JA Fagin) and grants from the American Thyroid Association (BR Untch), the American Surgical Association Foundation (BR Untch), the Paul LoGerfo Research Award from the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons (BR Untch) and the Charles A Dana Foundation/T32 5T32CA009512 (BR Untch). We thank the MSKCC Research Animal Resource Center and the following core labs for their support: Small Animal Imaging, Molecular Cytology, Bioinformatics, Pathology, the Integrative Genomics Operation funded by Cycle for Survival and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology. These studies were performed under a collaboration agreement with Kura Oncology, Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement: Authors Untch BR, Knauf JA, and Fagin JA are patent holders for the use of farnesyltransferase inhibitors to target Hras-mutant malignancies. Alan Ho has received consulting fees from Merck, BMS, Eisai, Genzyme, Novartis, Regeneron, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi Aventis.

References

- 1.Shima F, Matsumoto S, Yoshikawa Y, Kawamura T, Isa M, Kataoka T. Current status of the development of Ras inhibitors. J Biochem. 2015 Aug;158(2):91–9. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostrem JM, Shokat KM. Direct small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: from structural insights to mechanism-based design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016 Nov;15(11):771–85. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukahori M, Yoshida A, Hayashi H, Yoshihara M, Matsukuma S, Sakuma Y, et al. The associations between RAS mutations and clinical characteristics in follicular thyroid tumors: new insights from a single center and a large patient cohort. Thyroid. 2012 Jul;22(7):683–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volante M, Rapa I, Gandhi M, Bussolati G, Giachino D, Papotti M, et al. RAS mutations are the predominant molecular alteration in poorly differentiated thyroid carcinomas and bear prognostic impact. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Dec;94(12):4735–41. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricarte-Filho JC, Ryder M, Chitale DA, Rivera M, Heguy A, Ladanyi M, et al. Mutational profile of advanced primary and metastatic radioactive iodine-refractory thyroid cancers reveals distinct pathogenetic roles for BRAF, PIK3CA, and AKT1. Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 01;69(11):4885–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moura MM, Cavaco BM, Pinto AE, Leite V. High prevalence of RAS mutations in RET-negative sporadic medullary thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 May;96(5):E863–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011 Aug 26;333(6046):1154–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014 Mar 20;507(7492):315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whyte DB, Kirschmeier P, Hockenberry TN, Nunez-Oliva I, James L, Catino JJ, et al. K- and N-Ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein transferase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997 May 30;272(22):14459–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Makarewicz JM, Knauf JA, Johnson LK, Fagin JA. Transformation by Hras is consistently associated with mutant allele copy gains and is reversed by farnesyl transferase inhibition. Oncogene. 2013 Nov 18; doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.End DW, Smets G, Todd AV, Applegate TL, Fuery CJ, Angibaud P, et al. Characterization of the antitumor effects of the selective farnesyl protein transferase inhibitor R115777 in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 2001 Jan 1;61(1):131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berndt N, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. Targeting protein prenylation for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011 Oct 24;11(11):775–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner TB, Hahn SM, Gupta AK, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG, Bernhard EJ. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: an overview of the results of preclinical and clinical investigations. Cancer Res. 2003 Sep 15;63(18):5656–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kusakabe T, Kawaguchi A, Kawaguchi R, Feigenbaum L, Kimura S. Thyrocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2004 Jul;39(3):212–6. doi: 10.1002/gene.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, Peterse H, van der Valk M, Berns A. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2001 Dec;29(4):418–25. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Mitsutake N, LaPerle K, Akeno N, Zanzonico P, Longo VA, et al. Endogenous expression of Hras(G12V) induces developmental defects and neoplasms with copy number imbalances of the oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 May 12;106(19):7979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L, Sinha R, Knauf JA, Shah RH, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest. 2016 Mar 01;126(3):1052–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI85271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010 Jun 25;141(7):1117–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montero-Conde C, Ruiz-Llorente S, Dominguez JM, Knauf JA, Viale A, Sherman EJ, et al. Relief of feedback inhibition of HER3 transcription by RAF and MEK inhibitors attenuates their antitumor effects in BRAF-mutant thyroid carcinomas. Cancer Discov. 2013 May;3(5):520–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014 Jan 3;343(6166):84–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Ye Q, Viale A, Sander C, Solit DB, et al. (V600E)BRAF is associated with disabled feedback inhibition of RAF-MEK signaling and elevated transcriptional output of the pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Mar 17;106(11):4519–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900780106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young A, Lou D, McCormick F. Oncogenic and wild-type Ras play divergent roles in the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Cancer Discov. 2013 Jan;3(1):112–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratner N, Miller SJ. A RASopathy gene commonly mutated in cancer: the neurofibromatosis type 1 tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015 May;15(5):290–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parma J, Duprez L, Van Sande J, Hermans J, Rocmans P, Van Vliet G, et al. Diversity and prevalence of somatic mutations in the thyrotropin receptor and Gs alpha genes as a cause of toxic thyroid adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Aug;82(8):2695–701. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox AD, Der CJ, Philips MR. Targeting RAS Membrane Association: Back to the Future for Anti-RAS Drug Discovery? Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Apr 15;21(8):1819–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Makarewicz JM, Knauf JA, Johnson LK, Fagin JA. Transformation by Hras(G12V) is consistently associated with mutant allele copy gains and is reversed by farnesyl transferase inhibition. Oncogene. 2014 Nov 20;33(47):5442–9. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014 Nov;13(11):828–51. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castellano E, Santos E. Functional specificity of ras isoforms: so similar but so different. Genes Cancer. 2011 Mar;2(3):216–31. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014 Oct 23;159(3):676–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Rendueles ME, Ricarte-Filho JC, Untch BR, Landa I, Knauf JA, Voza F, et al. NF2 Loss Promotes Oncogenic RAS-Induced Thyroid Cancers via YAP-Dependent Transactivation of RAS Proteins and Sensitizes Them to MEK Inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2015 Nov;5(11):1178–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollag G, Clapp DW, Shih S, Adler F, Zhang YY, Thompson P, et al. Loss of NF1 results in activation of the Ras signaling pathway and leads to aberrant growth in haematopoietic cells. Nat Genet. 1996 Feb;12(2):144–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro AF, Rebhun JF, Clark GJ, Quilliam LA. Rheb binds tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and promotes S6 kinase activation in a rapamycin- and farnesylation-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2003 Aug 29;278(35):32493–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashar HR, James L, Gray K, Carr D, Black S, Armstrong L, et al. Farnesyl transferase inhibitors block the farnesylation of CENP-E and CENP-F and alter the association of CENP-E with the microtubules. J Biol Chem. 2000 Sep 29;275(39):30451–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crespo NC, Ohkanda J, Yen TJ, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor, FTI-2153, blocks bipolar spindle formation and chromosome alignment and causes prometaphase accumulation during mitosis of human lung cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001 May 11;276(19):16161–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lito P, Saborowski A, Yue J, Solomon M, Joseph E, Gadal S, et al. Disruption of CRAF-mediated MEK activation is required for effective MEK inhibition in KRAS mutant tumors. Cancer Cell. 2014 May 12;25(5):697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hancock JF, Paterson H, Marshall CJ. A polybasic domain or palmitoylation is required in addition to the CAAX motif to localize p21ras to the plasma membrane. Cell. 1990 Oct 05;63(1):133–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90294-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dekker FJ, Rocks O, Vartak N, Menninger S, Hedberg C, Balamurugan R, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of APT1 affects Ras localization and signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2010 Jun;6(6):449–56. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu J, Hedberg C, Dekker FJ, Li Q, Haigis KM, Hwang E, et al. Inhibiting the palmitoylation/depalmitoylation cycle selectively reduces the growth of hematopoietic cells expressing oncogenic Nras. Blood. 2012 Jan 26;119(4):1032–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-358960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Bruin EC, Cowell C, Warne PH, Jiang M, Saunders RE, Melnick MA, et al. Reduced NF1 expression confers resistance to EGFR inhibition in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014 May;4(5):606–19. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whittaker SR, Theurillat JP, Van Allen E, Wagle N, Hsiao J, Cowley GS, et al. A genome-scale RNA interference screen implicates NF1 loss in resistance to RAF inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2013 Mar;3(3):350–62. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauchamp EM, Woods BA, Dulak AM, Tan L, Xu C, Gray NS, et al. Acquired resistance to dasatinib in lung cancer cell lines conferred by DDR2 gatekeeper mutation and NF1 loss. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 Feb;13(2):475–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landis CA, Masters SB, Spada A, Pace AM, Bourne HR, Vallar L. GTPase inhibiting mutations activate the alpha chain of Gs and stimulate adenylyl cyclase in human pituitary tumours. Nature. 1989 Aug 31;340(6236):692–6. doi: 10.1038/340692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyons J, Landis CA, Harsh G, Vallar L, Grunewald K, Feichtinger H, et al. Two G protein oncogenes in human endocrine tumors. Science. 1990 Aug 10;249(4969):655–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2116665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, Dal Molin M, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011 Jul 20;3(92):92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishikawa G, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Matsubara A, Mori T, Taniguchi H, et al. Frequent GNAS mutations in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Cancer. 2013 Mar 05;108(4):951–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakravarty D, Santos E, Ryder M, Knauf JA, Liao XH, West BL, et al. Small-molecule MAPK inhibitors restore radioiodine incorporation in mouse thyroid cancers with conditional BRAF activation. J Clin Invest. 2011 Dec;121(12):4700–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI46382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagarajah J, Le M, Knauf JA, Ferrandino G, Montero-Conde C, Pillarsetty N, et al. Sustained ERK inhibition maximizes responses of BrafV600E thyroid cancers to radioiodine. J Clin Invest. 2016 Nov 01;126(11):4119–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI89067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ho AL, Grewal RK, Leboeuf R, Sherman EJ, Pfister DG, Deandreis D, et al. Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013 Feb 14;368(7):623–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothenberg SM, McFadden DG, Palmer EL, Daniels GH, Wirth LJ. Redifferentiation of iodine-refractory BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic papillary thyroid cancer with dabrafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Mar 01;21(5):1028–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumaz N, Marais R. Integrating signals between cAMP and the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signalling pathways. Based on the anniversary prize of the Gesellschaft fur Biochemie und Molekularbiologie Lecture delivered on 5 July 2003 at the Special FEBS Meeting in Brussels. FEBS J. 2005 Jul;272(14):3491–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Knauf JA, Basu S, Puxeddu E, Kuroda H, Santoro M, et al. Conditional expression of RET/PTC induces a weak oncogenic drive in thyroid PCCL3 cells and inhibits thyrotropin action at multiple levels. Mol Endocrinol. 2003 Jul;17(7):1425–36. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Missero C, Pirro MT, Di Lauro R. Multiple ras downstream pathways mediate functional repression of the homeobox gene product TTF-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 Apr;20(8):2783–93. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2783-2793.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Velasco JA, Acebro NA, Zannini M, Mart INPRJ, Di Lauro R, Santisteban P. Ha-ras Interference with Thyroid Cell Differentiation Is Associated with a Down-Regulation of Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 Phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 1998 Jun 01;139(6):2796–802. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johannessen CM, Johnson LA, Piccioni F, Townes A, Frederick DT, Donahue MK, et al. A melanocyte lineage program confers resistance to MAP kinase pathway inhibition. Nature. 2013 Dec 05;504(7478):138–42. doi: 10.1038/nature12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn. 2015 May;17(3):251–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.