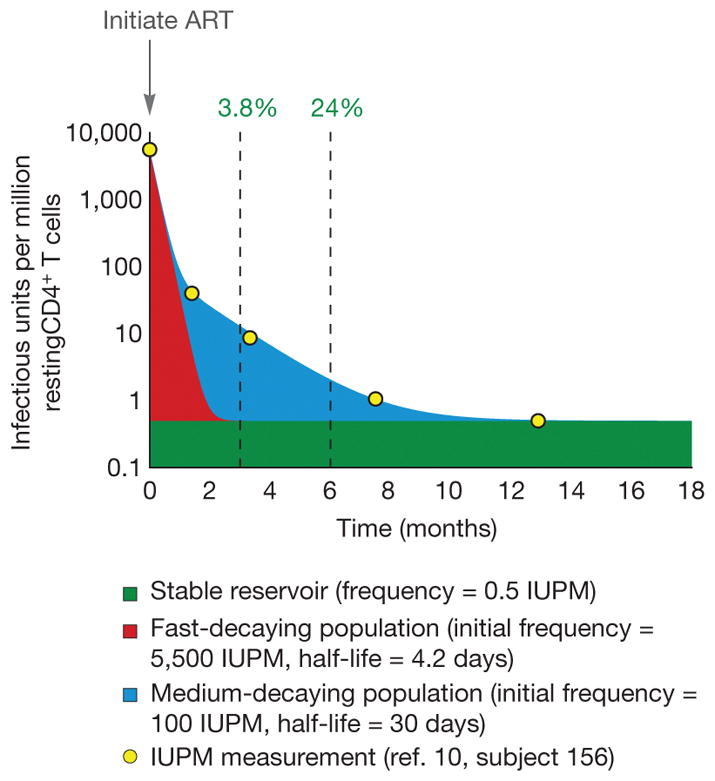

Figure 1. For the first six months of ART, the persistent latent reservoir makes up a minority of sampled sequences.

Yellow dots show longitudinal measurements of inducible, replication-competent HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells from one patient10. Infection frequency was measured by qVOA and is reported as infectious units per million cells (IUPM). Intact, unintegrated HIV-1 DNA in recently infected cells can be detected in this assay because cellular activation stimulates completion of the viral life cycle1,8,10. The solid-coloured regions show estimated sizes of the underlying populations that combine to yield the observed triphasic decay of IUPM. A latent reservoir (green, proportion shown at three and six months) is established before treatment and persists despite ART. This reservoir decays at a very slow rate5,6 that can be approximated as constant over the one-year period represented here. Initially, there is a large, rapidly decaying viral population (red) that is likely to include unintegrated viral genomes. A smaller population of infected cells decays at a moderate rate (blue). Consequently, at therapy initiation, less than 0.01% of resting CD4+ T cells with replication-competent virus belong to the stable reservoir, while 98% belong to the large, fast-decaying population. Only after a year of therapy would the stable reservoir exceed 95%. All patients in the study showed similar decay, in which the proportion of infected cells belonging to the latent reservoir did not stabilize within the first six months of therapy10. Note that cells with infectious provirus are generally outnumbered by orders of magnitude by cells containing defective provirus. The percentages given here therefore overestimate the proportion of all sampled HIV-1 DNA that represents the persistent latent reservoir of replication-competent virus.