Abstract

Oxidation of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC) by the nitrate radical (NO3) represents one of the important interactions between anthropogenic emissions related to combustion and natural emissions from the biosphere. This interaction has been recognized for more than 3 decades, during which time a large body of research has emerged from laboratory, field, and modeling studies. NO3-BVOC reactions influence air quality, climate and visibility through regional and global budgets for reactive nitrogen (particularly organic nitrates), ozone, and organic aerosol. Despite its long history of research and the significance of this topic in atmospheric chemistry, a number of important uncertainties remain. These include an incomplete understanding of the rates, mechanisms, and organic aerosol yields for NO3-BVOC reactions, lack of constraints on the role of heterogeneous oxidative processes associated with the NO3 radical, the difficulty of characterizing the spatial distributions of BVOC and NO3 within the poorly mixed nocturnal atmosphere, and the challenge of constructing appropriate boundary layer schemes and non-photochemical mechanisms for use in state-of-the-art chemical transport and chemistry–climate models.

This review is the result of a workshop of the same title held at the Georgia Institute of Technology in June 2015. The first half of the review summarizes the current literature on NO3-BVOC chemistry, with a particular focus on recent advances in instrumentation and models, and in organic nitrate and secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation chemistry. Building on this current understanding, the second half of the review outlines impacts of NO3-BVOC chemistry on air quality and climate, and suggests critical research needs to better constrain this interaction to improve the predictive capabilities of atmospheric models.

1 Introduction

The emission of hydrocarbons from the terrestrial biosphere represents a large natural input of chemically reactive compounds to Earth’s atmosphere (Guenther et al., 1995; Goldstein and Galbally, 2007). Understanding the atmospheric degradation of these species is a critical area of current research that influences models of oxidants and aerosols on regional and global scales. Nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) arising from combustion and microbial action on fertilizer are one of the major anthropogenic inputs that perturb the chemistry of the atmosphere (Crutzen, 1973). Nitrogen oxides have long been understood to influence oxidation cycles of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC), especially through photochemical reactions of organic and hydroperoxy radical intermediates (RO2 and HO2) with nitric oxide (NO) (Chameides, 1978).

The nitrate radical (NO3) arises from the oxidation of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) by ozone (O3) and occurs principally in the nighttime atmosphere due to its rapid photolysis in sunlight and its reaction with NO (Wayne et al., 1991; Brown and Stutz, 2012). The nitrate radical is a strong oxidant, reacting with a wide variety of volatile organic compounds, including alkenes, aromatics, and oxygenates as well as with reduced sulfur compounds. Reactions of NO3 are particularly rapid with unsaturated compounds (alkenes) (Atkinson and Arey, 2003). BVOC such as isoprene, monoterpenes, and sesquiterpenes typically have one or more unsaturated functionalities such that they are particularly susceptible to oxidation by O3 and NO3.

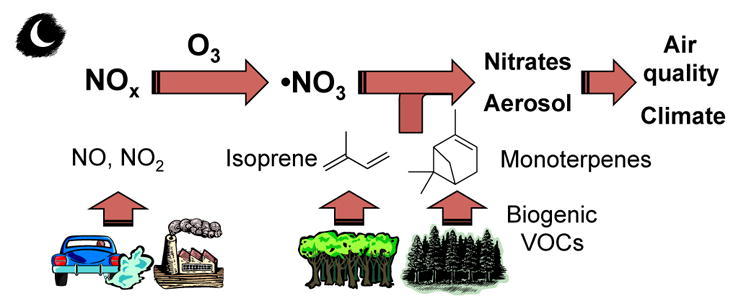

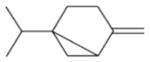

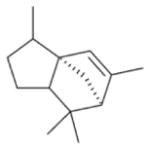

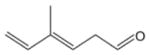

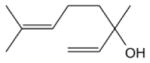

The potential for NO3 to serve as a large sink for BVOC was recognized more than 3 decades ago (Winer et al., 1984). Field studies since that time have shown that in any environment with moderate to large BVOC concentrations, a majority of the NO3 radical oxidative reactions are with BVOC rather than VOC of anthropogenic origin (Brown and Stutz, 2012). This interaction gives rise to a mechanism that couples anthropogenic NOx emissions with natural BVOC emissions (Fry et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2015a). Although it is one of several such anthropogenic–biogenic interactions (Hoyle et al., 2011), reactions of NO3 with BVOC are an area of intense current interest and one whose study has proven challenging. These challenges arise from the more limited current database of laboratory data for NO3 oxidation reactions relative to those of other common atmospheric oxidants such as hydroxyl radical (OH) and O3. The mixing state of the night-time atmosphere and the limitations it imposes for characterization of nocturnal oxidation chemistry during field measurements and within atmospheric models present a second challenge to this field of research. Figure 1 illustrates these features of nighttime NO3-BVOC chemistry.

Figure 1.

Schematic of nighttime NO3-BVOC chemistry.

Reactions of NO3 with BVOC have received increased attention in the recent literature as a potential source of secondary organic aerosol (SOA) (Pye et al., 2010; Fry et al., 2014; Boyd et al., 2015). This SOA source is intriguing for several reasons. First, although organics are now understood to comprise a large fraction of total aerosol mass, and although much of these organics are secondary, sources of SOA remain difficult to characterize, in part due to a large number of emission sources and potential chemical mechanisms (Zhang et al., 2007; Hallquist et al., 2009; Jimenez et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2010). Analysis of aerosol organic carbon shows that a large fraction is modern, arising either from biogenic hydrocarbon emissions or biomass burning sources (e.g., Schichtel et al., 2008; Hodzic et al., 2010). Conversely, field data in regionally polluted areas indicate strong correlations between tracers of anthropogenic emissions and SOA, which suggests that anthropogenic influences can lead to production of SOA from modern (i.e., non-fossil) carbon (e.g., Weber et al., 2007). Model studies confirm that global observations are best simulated with a biogenic carbon source in the presence of anthropogenic pollutants (Spracklen et al., 2011). Reactions of NO3 with BVOC are one such mechanism that may lead to anthropogenically influenced biogenic SOA (Hoyle et al., 2007), and it is important to quantify the extent to which such reactions can explain sources of SOA.

Second, some laboratory and chamber studies suggest that SOA yields from NO3 oxidation of common BVOC, such as isoprene and selected monoterpenes, are greater than that for OH or O3 oxidation (Hallquist et al., 1997b; Griffin et al., 1999; Spittler et al., 2006; Ng et al., 2008; Fry et al., 2009, 2011, 2014;; Rollins et al., 2009; Boyd et al., 2015). However, among the monoterpenes, the SOA yields may be much more variable for NO3 oxidation than for other oxidants, with anomalously low SOA yields in some cases and high SOA yields in others (Draper et al., 2015; Nah et al., 2016b).

Third, not only is NO3-BVOC chemistry a potentially efficient SOA formation mechanism, it is also a major pathway for the production of organic nitrates (von Kuhlmann et al., 2004; Horowitz et al., 2007), a large component of oxidized reactive nitrogen that may serve as either a NOx reservoir or NOx sink. Results from recent field measurements have shown that organic nitrates are important components of ambient OA (Day et al., 2010; Rollins et al., 2012; Fry et al., 2013; Ayres et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015a, b; Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016). Furthermore, within the last several years, the capability to measure both total and speciated gas-phase and particle-phase organic nitrates has been demonstrated (Fry et al., 2009, 2013, 2014; Rollins et al., 2010, 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Nah et al., 2016b). The life-times of organic nitrates derived from BVOC-NO3 reaction with respect to hydrolysis, photooxidation, and deposition play an important role in the NOx budget and formation of O3 and SOA. These processes appear to depend strongly on the parent VOC and oxidation conditions and must be better constrained for understanding organic nitrate lifetimes in the atmosphere (Darer et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012b; Boyd et al., 2015; Pye et al., 2015; Rindelaub et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Nah et al., 2016b).

Fourth, incorporation of SOA yields for NO3-BVOC reactions into regional and global models indicates that these reactions could be a significant, or in some regions even dominant, SOA contributor (Hoyle et al., 2007; Pye et al., 2010, 2015; Chung et al., 2012; Fry and Sackinger, 2012; Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016). Model predictions of organic aerosol formation from NO3-BVOC until recently have been difficult to verify directly from field measurements. Recent progress in laboratory and field studies have provided some of the first opportunities to develop coupled gas and particle systems to describe mechanistically and predict SOA and organic nitrate formation from NO3-BVOC reactions (Pye et al., 2015).

Finally, analyses from several recent field studies examining diurnal variation in the organic and/or nitrate content of aerosols conclude that nighttime BVOC oxidation through NO3 radicals constitutes a large organic aerosol source (Rollins et al., 2012; Fry et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2015a, b; Kiendler-Scharr et al., 2016). Although such analyses may correct their estimates of aerosol production for the variation in boundary layer depth, field measurements at surface level are necessarily limited in their ability to accurately assess the atmospheric chemistry in the overlying residual layer or even the gradients that may exist within the relatively shallow nocturnal boundary layer (Stutz et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2007b). Thus, although there is apparent consistency between recent results from both modeling and field studies, the vertically stratified structure of the nighttime atmosphere makes such comparisons difficult to evaluate critically. There is a limited database of nighttime aircraft measurements that has probed this vertical structure with sufficient chemical detail to assess NO3-BVOC reactions (Brown et al., 2007a; Brown et al., 2009), and some of these data show evidence for an OA source related to this chemistry, especially at low altitude (Brown et al., 2013). A larger database of aircraft and/or vertically resolved measurements is required, however, for comprehensive comparisons to model predictions.

The purpose of this article is to review the current literature on the chemistry of NO3 and BVOC to critically assess the current state of the science. The review focuses on BVOC emitted from terrestrial vegetation. The importance of NO3 reactions with reduced sulfur compounds, such as dimethyl sulfide in marine ecosystems, is well known (Platt et al., 1990; Yvon et al., 1996; Allan et al., 1999, 2000; Vrekoussis et al., 2004; Stark et al., 2007; Osthoff et al., 2009) but is outside of the scope of this review. Key uncertainties include chemical mechanisms, yields of major reaction products such as SOA and organic nitrogen, the potential for NO3 and BVOC to interact in the ambient atmosphere, and the implications of that interaction for current understanding of air quality and climate. The review stems from an International Global Atmospheric Chemistry (IGAC) and US National Science Foundation (NSF) sponsored workshop of the same name held in June 2015 at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Atlanta, GA, USA). Following this introduction, Sect. 2 of this article reviews the current literature in several areas relevant to the understanding of NO3-BVOC atmospheric chemistry. Section 3 outlines perspectives on the implications of this chemistry for understanding climate and air quality, its response to current emission trends, and its relevance to implementation of control strategies. Finally, the review concludes with an assessment of the impacts of NO3-BVOC reactions on air quality, visibility, and climate.

2 Review of current literature

This section contains a literature review of the current state of knowledge of NO3-BVOC chemistry with respect to (1) reaction rate constants and mechanisms from laboratory and chamber studies; (2) secondary organic aerosol yields, speciation, and particle-phase chemistry; (3) heterogeneous reactions of NO3 and their implications for NO3-BVOC chemistry; (4) instrumental methods for analysis of reactive nitrogen compounds, including NO3, organic nitrates, and nitrogen-containing particulate matter; (5) field observations relevant to the understanding of NO3 and BVOC chemistry; and (6) models of NO3-BVOC chemistry.

2.1 NO3-BVOC reaction rates and chemical mechanisms

2.1.1 Reaction rates

Among the numerous BVOC emitted into the troposphere, kinetic data for NO3 oxidation have been provided for more than 40 compounds. The most emitted/important BVOC have been subject to several kinetic studies, using both absolute and relative methods, which are evaluated to determine rate constants by IUPAC (Table 1). This is the case for isoprene, α-pinene, β-pinene, and 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol (MBO). However, for isoprene, β-pinene, and MBO, rate constants obtained by different studies range over a factor of 2. For some other terpenes, only few kinetic studies have been carried out, with at least one absolute rate determination. This is the case for sabinene, 2-carene, camphene, d-limonene, α-phellandrene, myrcene, γ -terpinene, and terpinolene. For these compounds, experimental data agree within 30–40 %, except α-phellandrene and terpinolene for which discrepancies are larger. For other BVOC, including other terpenes, sesquiterpenes, and oxygenated species, rate constants are mostly based on a single determination and highly uncertain. For these compounds, further rate constant determinations and end-product measurements are essential to better evaluate the role of NO3 in their degradation. The ability to predict the NO3-BVOC rate constants using structure–activity relationships (SARs) has been improved. A recent study (Kerdouci et al., 2010; Kerdouci, 2014) presented a new SAR parameterization based on 180 NO3-VOC reactions. The method is capable of predicting 90 % of the rate constants within a factor of 2.

Table 1.

Reaction rate constants of NO3+ BVOC.

| Compound | k(NO3+BVOC) (cm3 molecule−1 s−1)a | Temperature (K) | Technique/reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

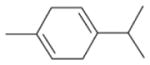

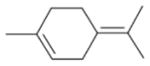

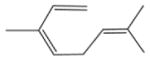

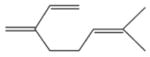

Isoprene

|

(5.94 ± 0.16)×10−13 | 295 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1984) |

| (1.30 ± 0.14)×10−12 | 298 | DF-MS/(Benter and Schindler, 1988) | |

| (3.03 ± 0.45)×10−12exp[−(450 ± 70)/T] | 251–281 | F-LIF/(Dlugokencky and Howard, 1989) | |

| (6.52 ± 0.78)×10−13 | 297 | F-LIF/(Dlugokencky and Howard, 1989) | |

| (1.21 ± 0.20)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Barnes et al., 1990) | |

| (7.30 ± 0.44)×10−13 | 298 | DF-MS/(Wille et al., 1991) | |

| (8.26 ± 0.60)×10−13 | 298 | DF-MS/(Wille et al., 1991) | |

| (1.07 ± 0.20)×10−12 | 295 | PR-A/(Ellermann et al., 1992) | |

| (6.86 ± 0.55)×10−13 | 298 | RR/(Berndt and Boge, 1997b) | |

| (7.3 ± 0.2)×10−13 | 298 | F-CIMS/(Suh et al., 2001) | |

| (6.24 ± 0.11)×10−13 | 295 | RR/(Zhao et al., 2011b) | |

| 6.5×10−13 (Δlog k: ± 0.15) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

α-pinene

|

(5.82 ± 0.16)×10−12 | 295 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1984) |

| (1.19 ± 0.31)×10−12exp[(490 ± 70)/T] | 261–383 | F-LIF/(Dlugokencky and Howard, 1989) | |

| (6.18 ± 0.94)×10−12 | 298 | F-LIF/(Dlugokencky and Howard, 1989) | |

| (6.56 ± 0.94)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Barnes et al., 1990) | |

| (3.5 ± 1.4)×10−13exp[(841 ± 144)/T] | 298–423 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

| (5.9 ± 0.8)×10−12 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

| (5.82 ± 0.56)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Kind et al., 1998) | |

| (4.88 ± 0.46)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Stewart et al., 2013) | |

| 6.2×10−12 (Δlog k : ± 0.1) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

β-pinene

|

(2.36 ± 0.10)×10−12 | 295 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1984) |

| (2.38 ± 0.05)×10−12 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1988) | |

| (1.1 ± 0.4)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Kotzias et al., 1989) | |

| (2.81 ± 0.47)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Barnes et al., 1990) | |

| (1.6 ± 1.5)×10−10exp[(−1248 ± 36)/T] | 298–293 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

| (2.1 ± 0.4)×10−12 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

| (2.81 ± 0.56)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Kind et al., 1998) | |

| 2.5×10−12 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Sabinene

|

(1.01 ± 0.03)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1990) |

| (1.07 ± 0.16)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1999) | |

| (2.3 ± 1.3)×10−10exp[(−940 ± 200)/T] | 298–393 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1999) | |

| 1.0×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.15) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Camphene

|

(6.54 ± 0.16)×10−13 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1990) |

| (3.1 ± 0.5)×10−12exp[(−481 ± 55)/T] | 298–433 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

| (6.2 ± 2.1)×10−13 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martinez et al., 1998) | |

|

| |||

2-carene

|

(1.87 ± 0.11)×10−11 | 295 | RR/(Corchnoy and Atkinson, 1990) |

| (2.16 ± 0.36)×10−11 | 295 | RR/(Corchnoy and Atkinson, 1990) | |

| (1.66 ± 0.18)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| (1.4 ± 0.7)×10−12exp[(741 ± 190)/T] | 298–433 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| 2.0×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

3-carene

|

(1.01 ± 0.02)×10−11 | 295 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1984) |

| (8.2 ± 1.2)×10−11 | 298 | RR/(Barnes et al., 1990) | |

| 9.1×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Δ-limonene

|

(1.31 ± 0.04)×10−11 | 295 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1984) |

| (1.12 ± 0.17)×10−11 | 298 | RR/(Barnes et al., 1990) | |

| (9.4 ± 0.9)×10−12 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| 1.2×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

α-phellandrene

|

(8.52 ± 0.63)×10−11 | 294 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1985) |

| (5.98 ± 0.20)×10−11 | 298 | RR/(Berndt et al., 1996) | |

| (4.2 ± 1.0)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| (1.9 ± 1.3)×10−9exp[−(1158 ± 270)/T] | 298–433 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| 7.3×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.15) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

β-phellandrene

|

(7.96 ± 2.82)×10−12 | 297 | RR/(Shorees et al., 1991) |

|

| |||

α-terpinene

|

(1.82 ± 0.07)×10−10 | 294 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1985) |

| (1.03 ± 0.06)×10−10 | 298 | RR/(Berndt et al., 1996) | |

| 1.8×10−10 (Δlog k : ± 0.25) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

γ-terpinene

|

(2.94 ± 0.05)×10−11 | 294 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1985) |

| (2.4 ± 0.7)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| 2.9×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Terpinolene

|

(9.67 ± 0.51)×10−11 | 295 | RR/(Corchnoy and Atkinson, 1990) |

| (5.2 ± 0.9)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| (6.12 ± 0.52)×10−11 | 298 | RR/(Stewart et al., 2013) | |

| 9.7×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.25) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Ocimene (cis, trans)

|

(2.23 ± 0.06)×10−11 | 294 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1985) |

| 2.2×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.15) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Myrcene

|

(1.06 ± 0.02)×10−11 | 294 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1985) |

| (1.28 ± 0.11)×10−11 | 298 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| (2.2± 0.2)×10−12exp[(523 ± 35)/T] | 298–433 | DF-LIF/(Martínez et al., 1999) | |

| 1.1×10−11 (Δlog k : ± 0.12) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

α-cedrene

|

(0.82 ± 0.30)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Shu and Atkinson, 1995) |

|

| |||

α-copaene

|

(1.6 ± 0.6)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Shu and Atkinson, 1995) |

|

| |||

β-caryophyllene

|

(1.9 ± 0.8)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Shu and Atkinson, 1995) |

|

| |||

α-humulene

|

(3.5 ± 1.3)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Shu and Atkinson, 1995) |

|

| |||

Longifolene

|

(6.8 ± 2.1)×10−13 | 296 | RR/(Shu and Atkinson, 1995) |

|

| |||

Isolongifolene

|

(3.9 ± 1.6)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999b) |

|

| |||

Alloisolongifolene

|

(1.4 ± 0.7)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999b) |

|

| |||

α-neoclovene

|

(8.2 ± 4.6)×10−12 | 298 | RR/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999b) |

|

| |||

2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol

|

4.6×10−14exp[−(400 ± 35)/T] | 267–400 | F-A/(Rudich et al., 1996) |

| (1.21 ± 0.09)×10−14 | 298 | F-A/(Rudich et al., 1996) | |

| (2.1 ± 0.3)×10−14 | 294 | DF-A/(Hallquist et al., 1996) | |

| (1.55 ± 0.55)×10−14 | 294 | RR/(Hallquist et al., 1996) | |

| (8.7 ± 3.0)×10−14 | 298 | RR/(Fantechi et al., 1998b) | |

| (1.0 ± 0.2)×10−14 | 297 | RR/(Noda et al., 2002) | |

| (1.1 ± 0.1)×10−14 | 297 | RR/(Noda et al., 2002) | |

| 1.2×10−14 (Δlog k : ± 0.2) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

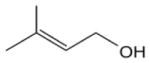

3-methyl-2-buten-1-ol

|

(1.0 ± 0.1)×10−12 | 297 | RR/(Noda et al., 2002) |

|

| |||

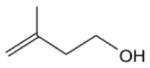

3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol

|

(2.7 ± 0.2)×10−13 | 297 | RR/(Noda et al., 2002) |

|

| |||

|

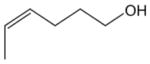

cis-3-hexen-1-ol |

(2.72 ± 0.83)×10−13 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1995) |

| (2.67 ± 0.42)×10−13 | 298 | DF-CEAS/(Pfrang et al., 2006) | |

|

| |||

|

trans-3-hexen-1-ol |

(4.43 ± 0.91)×10−13 | 298 | DF-CEAS/(Pfrang et al., 2006) |

|

| |||

cis-4-hexen-1-ol

|

(2.93 ± 0.48)×10−13 | 298 | DF-CEAS/(Pfrang et al., 2006) |

|

| |||

|

trans-2-hexen-1-ol |

(1.30 ± 0.24)×10−13 | 298 | DF-CEAS/(Pfrang et al., 2006) |

|

| |||

|

cis-2-hexen-1-ol |

(1.56 ± 0.24)×10−13 | 298 | DF-CEAS/(Pfrang et al., 2006) |

|

| |||

|

trans-2-hexenal |

(1.21 ± 0.44)×10−14 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1995) |

| (1.36 ± 0.29)×10−14) | 295 | RR/(Zhao et al., 2011b) | |

| (4.7 ± 1.5)×10−15 | 294 | AR/(Kerdouci et al., 2012) | |

|

| |||

| 4-methylenehex-5-enal |

(4.75 ± 0.35)×10−13 | 296 | RR/(Baker et al., 2004) |

|

| |||

| (3Z)-4-methylhexa-3,5-dienal |

(2.17 ± 0.30)×10−12 | 296 | RR/(Baker et al., 2004) |

|

| |||

(3E)-4-methylhexa-3,5-dienal

|

(1.75 ± 0.27)×10−12 | 296 | RR/(Baker et al., 2004) |

|

| |||

4-methylcyclohex-3-en-1-one

|

(1.81 ± 0.35)×10−12 | 296 | RR/(Baker et al., 2004) |

|

| |||

|

cis-3-hexenyl acetate |

(2.46 ± 0.75)×10−13 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1995) |

|

| |||

Methyl vinyl ketone

|

< 1.2×10−16 | 298 | F-A/(Rudich et al., 1996) |

| < 6×10−16 | 296 | DF- RR/(Kwok et al., 1996) | |

| (3.2 ± 0.6)×10−16 | 296 | LIF/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999a) | |

| (5.0 ± 1.2)×10−16 | 296 | RR/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999a) | |

| < 6×10−16 | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Methacrolein

|

(4.46 ± 0.58)×10−15 | 296 | RR/(Kwok et al., 1996) |

| (3.08 ± 0.18)×10−15 | 298 | RR/(Chew et al., 1998) | |

| (3.50 ± 0.15)×10−15 | 298 | RR/(Chew et al., 1998) | |

| (3.72 ± 0.47)×10−15 | 296 | RR/(Canosa-Mas et al., 1999a) | |

| 3.4×10−15 (Δlog k : ± 0.15) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Pinonaldehyde

|

(2.40 ± 0.38)×10−14 | 299 | RR/(Hallquist et al., 1997a) |

| (6.0 ± 2.0)×10−14 | 300 | RR/(Glasius et al., 1997) | |

| (2.0 ± 0.9)×10−14 | 296 | RR/(Alvarado et al., 1998) | |

| 2.0×10−14 (Δlog k : ± 0.25) | 298 | IUPAC | |

|

| |||

Linalool

|

(1.12 ± 0.40)×10−11 | 296 | RR/(Atkinson et al., 1995) |

|

| |||

α-terpineol

|

(1.6 ± 0.4)×10−11 | 297 | RR/(Jones and Ham, 2008) |

|

| |||

Sabinaketone

|

(3.6 ± 2.3)×10−16 | 296 | RR/(Alvarado et al., 1998) |

|

| |||

Caronaldehyde

|

(2.5 ± 1.1)×10−14 | 296 | RR/(Alvarado et al., 1998) |

Given uncertainties are those provided by the authors of the kinetic studies. The procedures used to calculate them are not detailed here, as they often differ from one study to another. Readers are referred to the original papers for more information on the uncertainties’ determination.

RR: relative rate; DF-MS: discharge flow–mass spectrometry; DF-LIF: discharge flow–laser–induced fluorescence; DF-A: discharge flow–absorption; DF-CEAS: discharge flow–cavity–enhanced absorption spectroscopy; F-LIF: flow system–laser–induced fluorescence; F-CIMS: flow system–chemical ionization mass spectrometry; F-A: flow system–absorption; PR-A: pulse radiolysis–absorption; AR: absolute rate in simulation chamber.

2.1.2 Mechanisms

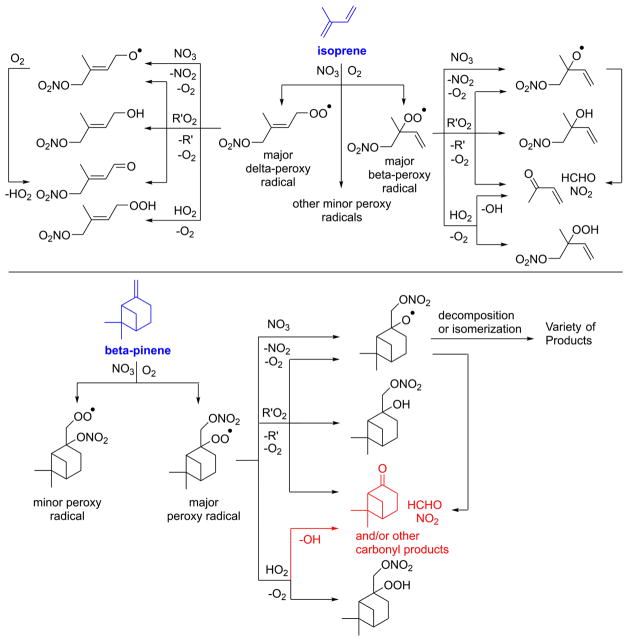

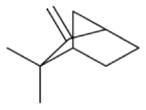

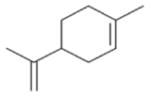

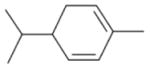

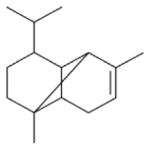

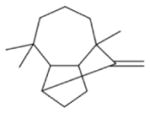

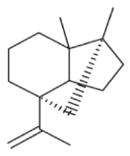

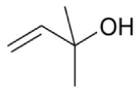

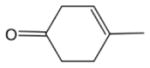

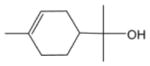

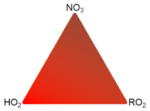

In general, NO3 reacts with unsaturated VOC by addition to a double bond (Wayne et al., 1991), though hydrogen abstraction may occur, most favorably for aldehydic species (Zhang and Morris, 2015). The location and likelihood of the NO3 addition to a double bond depends on the substitution on each end of the double bond, with the favored NO3 addition position being the one resulting in the most substituted carbon radical. In both cases, molecular oxygen adds to the resulting radical to form a peroxy radical (RO2). For example, the major RO2 isomers produced from isoprene and β-pinene oxidation via NO3 are shown in Fig. 2. The RO2 distribution for isoprene oxidation by OH has been shown to be dependent on the RO2 lifetime (Peeters et al., 2009, 2014), but no similar theoretical studies have been conducted on the NO3 system. Schwantes et al. (2015) determined the RO2 isomer distribution at an RO2 lifetime of ~ 30 s for isoprene oxidation via NO3. More theoretical and experimental studies are needed to understand the influence of RO2 lifetime, which is long at night (~ 50–200 s for isoprene; Schwantes et al., 2015), on the RO2 isomer distribution, as this distribution influences the formation of all subsequent products (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Condensed reaction mechanism for isoprene and β-pinene oxidation via NO3 (adapted from Schwantes et al., 2015 and Boyd et al., 2015). For brevity, only products generated from the dominant peroxy radicals (RO2) are shown. R′ represents an alkoxy radical, carbonyl compound, or hydroxy compound. Two of the largest uncertainties in β-pinene oxidation are shown in red: (1) quantification of product yields from the RO2+ HO2 channel and (2) identification of carbonyl products formed from RO2 reaction with NO3, RO2, or HO2 (see text for more details).

The fate of RO2 determines the subsequent chemistry. During the nighttime in the ambient atmosphere, RO2 will isomerize or react with another RO2, NO3, or HO2. In order to monitor RO2 isomerization reaction products, RO2 life-times must be long in laboratory studies similar to the ambient atmosphere (e.g., Peeters et al., 2009; Crounse et al., 2011). The NO3 plus BVOC (NO3+ BVOC) reaction can be a source of nighttime HO2 and OH radicals (Platt et al., 1990). Reaction with NO is a minor peroxy radical fate at night (Pye et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2015). Few laboratory studies have contrasted the fates of RO2 and their impacts on gas-phase oxidation and aerosol formation (Ng et al., 2008; Boyd et al., 2015; Schwantes et al., 2015). Boyd et al. (2015) examined how RO2 fate influences SOA formation and yields, and studied the competition between the RO2-NO3 and RO2-HO2 channels for β-pinene. Boyd et al. (2015) determined that the SOA yields for both channels are comparable, indicating that the volatility distribution of products may not be very different for the different RO2 fates. In contrast, the results from NO3 oxidation of smaller BVOC, such as isoprene, show large differences in SOA yields depending on the RO2 fate (Ng et al., 2008), with larger SOA yields for second-generation NO3 oxidation (Rollins et al., 2009).

The well-established gas-phase first-generation products from the major β- and δ-RO2 isomers formed from isoprene oxidation are shown in Fig. 2 (adapted from Schwantes et al., 2015). Some of the products are common between all the pathways, such as methyl vinyl ketone for the dominant β-RO2 isomer. However, some products are unique to only one channel (e.g., hydroxy nitrates form from RO2-RO2 reactions and nitrooxy hydroperoxides form from RO2-HO2 reactions). In this case, the overall nitrate yield and the specific nitrates formed from isoprene depend on the initial RO2 isomer distribution and the fate of the RO2. Furthermore, the distribution of gas-phase products will then influence the formation of SOA. For isoprene, the SOA yields from RO2-RO2 reactions are ~ 2 times greater than the yield from RO2-NO3 reactions (Ng et al., 2008). The less well-established first-generation products from β-pinene oxidation are also shown in Fig. 2 (adapted from Boyd et al., 2015). There are still lingering uncertainties (shown in red) in the first-generation products formed from β-pinene oxidation. The product yields from the RO2+ HO2 channel are not well constrained, largely due to the unavailability of authentic standards. In Fig. 2, a carbonyl product is assumed to form directly from the RO2 + HO2 reaction instead of proceeding through an alkoxy intermediate consistent with theoretical calculations from different compounds (Hou et al., 2005a, b; Praske et al., 2015). This is also uncertain, as few theoretical studies have been conducted on large molecules like β-pinene. The identification of the carbonyl compound(s) produced from RO2 reaction with NO3, RO2, or HO2 is unknown. Hallquist et al. (1999) detected a low molar yield (0–2 %; Table 2) of nopinone from β-pinene NO3 oxidation. Further laboratory studies identifying other carbonyl products are recommended.

Table 2.

Oxidation products and SOA yields observed in previous studies of NO3-BVOC reactions. Except where noted, carbonyl and organic nitrate molar yields represent initial gas-phase yields measured by FTIR spectroscopy (carbonyl and organic nitrate) or thermal desorption laser-induced fluorescence (TD-LIF) (organic nitrate only; Rollins et al., 2010; Fry et al., 2013). In some cases, the ranges reported correspond to wide ranges of organic aerosol loading, listed in the rightmost column. Where possible, the mass yield at 10 μg m−3 is reported for ease of comparison.

| BVOC | Carbonyl molar yield | Organic nitrate molar yield | SOA mass yield | Corresponding OA loading or other relevant information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoprene | 62–78 % (Rollins et al., 2009) | 2 % (14 % after further oxidation) (Rollins et al., 2009) | Nucleation (1 μg m−3) | |

| 4–24 % (Ng et al., 2008) | 3–70 μg m−3; 12 % at 10 μg m −3 | |||

|

| ||||

| α-pinene | 58–66 % (Wangberg et al., 1997); 69–81 % (Berndt and Boge, 1997a); 65–72 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 39–58 % (Spittler et al., 2006) | 14 % (Wangberg et al., 1997); 12–18 % (Berndt and Boge, 1997b); 18–25 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 11–29 % (Spittler et al., 2006); 10 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 0.2–16 % (Hallquist et al., 1999) | Nucleation; 0.5 % at 10 ppt N2O5 reacted, 7 % at 100 ppt N2O5 reacteda |

| 4 or 16 % (Spittler et al., 2006) | Values for 20 % RH and dry conditions, respectively, at M∞b | |||

| 1.7–3.6 % (Nah et al., 2016a) | 1.2–2.5 μg m−3 | |||

| 0 % (Fry et al., 2014) | Both nucleation and ammonium sulfate seeded | |||

| 9 % (Perraud et al., 2010) | Nucleation at 1 ppm N2O5 and 1 ppm α-pinene; OA is 480 μg m−3 assuming density is1.235 g cm−3 | |||

|

| ||||

| β-pinene | 0–2 % (Hallquist et al., 1999) | 51–74 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 40 % (Fry et al., 2009); 22 % (Fry et al., 2014); 45–74 % of OA mass (Boyd et al., 2015) | 32–89 % (Griffin et al., 1999) | 32–470 μg m−3 ; low end closest to 10 μg m− 3 |

| 7–40 % (Moldanova and Ljungstrom, 2000) using new model to reinterpret data from Hallquist et al. (1999) (10–52 %) | 7–10 % at 7 ppt N2O5 reacted; 40–52 % at 39 ppt N2O5 reacted | |||

| 50 % (Fry et al., 2009) | 40 μg m−3; same yield at both 0 and 60 % RH | |||

| 33–44 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 10 μg m−3 c | |||

| 27–104 % (Boyd et al., 2015) | 5–135 μg m−3, various seeds and RO2 fate regimes; 50 % for experiments near 10 μg m −3 | |||

|

| ||||

| Δ-carene | 0–3 % (Hallquist et al., 1999) | 68–74 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 77 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 13–72 % (Griffin et al., 1999) | 24–310 μg m−3 ; low end closest to 10 μg m− 3 |

| 12–49 % (Moldanova and Ljungstrom, 2000) using new model to reinterpret data from Hallquist et al. (1999) (15–62 %) | 7–395 ppt N2O 5 reacted; 12–15 % at 6.8 ppt N2O5 reacted | |||

| 38–65 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 10 μg m−3 c | |||

|

| ||||

| Limonene | 69 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 25–33 % (Spittler et al., 2006) | 48 % (Hallquist et al., 1999); 63–72 % (Spittler et al., 2006); 30 % (Fry et al., 2011); 54 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 14–24 % (Moldanova and Ljungstrom, 2000) using new model to reinterpret data from Hallquist et al. (1999) (17 %) | 10 ppt N2O5 reacted; higher number in Moldanova and Ljungstrom (2000) from an additional injection of 7 ppt N2O5 and accounting for secondary reactions |

| 21 or 40 % (Spittler et al., 2006) | Ammonium sulfate or organic seed, respectively, at M∞b | |||

| 25–40 % (Fry et al., 2011) | Nucleation to 10 μg m−3 (second injection of oxidant) | |||

| 44–57 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 10 μg m−3 c | |||

|

| ||||

| Sabinene | 14–76 % (Griffin et al., 1999) | 24–277 μg m−3 ; low end closest to 10 μg m− 3 | ||

| 25–45 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 10 μg m−3 c | |||

|

| ||||

| β-caryophyllene | 91–146 % (Jaoui et al., 2013) | 60–130 μg m−3 ; low end closest to 10 μg m− 3 | ||

| 86 % (Fry et al., 2014) | 10 μg m−3 | |||

The authors assume that N2O5 reacted is equal to BVOC reacted. The anomalously low 0.2 % yield observed at 390 ppt N2O5 reacted is a lower limit; Hallquist et al. note that the number–size distribution for that experiment fell partly outside the measured range.

M∞ corresponds to extrapolated value at highest mass loading. Organic seed aerosol in these experiments was generated from O3 + BVOC. Full dataset was shown only for limonene, where asymptote is 400 μg m−3.

Yield range corresponds to two different methods of calculating ΔBVOC.

Given the limited number of studies that have considered the fate of the peroxy radical, generalizations cannot yet be made for all VOC. Indeed, more studies are needed to determine systematically how gas-phase products and SOA yields are influenced by reactions of RO2. More specifically, for all chamber experiments, constraining the fate and lifetime of RO2 is required to attribute product and SOA yields to a specific pathway. As shown in Table 2 in Sect. 2.2, the nitrate yields and SOA yields for NO3-induced degradation of many VOC vary significantly between different studies. This is likely, in part, a result of each experiment having a different distribution of RO2 fates, but may also arise from vapor wall losses.

In general, there are very few mechanistic studies for NO3 relative to other oxidants. Furthermore, the elucidation of mechanisms is limited by the fact that most studies provide overall yields of organic nitrates (without individual identification of the species) and/or identification (without quantification) due to the lack of standards.

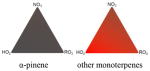

2.2 Organic aerosol yields, speciation, and particle-phase chemistry

Several papers have reported chamber studies to measure the organic aerosol yield and/or gaseous and aerosol-phase oxidation product distribution from NO3-BVOC reactions. These are summarized in Table 2. In general, these experimental results show that monoterpenes are efficient sources of SOA, with reported yields variable but consistently above 20 %, with the notable exception of α-pinene (yields 0–15 %). This anomalous monoterpene also has a much larger product yield of carbonyls instead of organic nitrates compared to the others. This difference among monoterpenes was investigated in the context of the competition between O3 and NO3 oxidation (Draper et al., 2015), in which shifting from O3-dominated to NO3-dominated oxidation was observed to suppress SOA formation from α-pinene, but not from β-pinene, Δ-carene, or limonene. The smaller isoprene has substantially lower SOA yields (2–24 %), and the only sesquiterpene studied, β-caryophyllene, has a much larger yield (86–150 %) than the monoterpenes.

In general, these chamber experiments are conducted under conditions that focus on first-generation oxidation only, but further oxidation can continue to change SOA loadings in the real atmosphere (e.g., Rollins et al., 2009; Chacon-Madrid et al., 2013). Recent experiments showed that particulate organic nitrates formed from β-pinene-NO3 are resilient to photochemical aging, while those formed from α-pinene-NO3 evaporate more readily (Nah et al., 2016b).

Other chamber studies have not reported SOA mass yields or gas-phase product measurements but have otherwise demonstrated the importance of NO3-BVOC reactions to SOA production. These studies have identified β-pinene and Δ-carene as particularly efficient sources of SOA upon NO3 oxidation (Hoffmann et al., 1997), confirmed the greater aerosol-forming potential from β-pinene versus α-pinene (Bonn and Moortgat, 2002), and reported Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and aerosol mass spectrometry (AMS) measurements of the composition of organic nitrates detected in aerosol formed from NO3-isoprene, α-pinene, β-pinene, Δ-carene, and limonene reactions (Bruns et al., 2010).

Relative humidity (RH) can be an important parameter, as it affects the competition between NO3-BVOC reactions and heterogeneous uptake of N2O5. Among existing laboratory studies, only a few have focused on the effect of RH on SOA formation from NO3-initiated oxidation (Bonn and Moortgat, 2002; Spittler et al., 2006; Fry et al., 2009; Boyd et al., 2015). The impact of RH might be important, especially at night and during the early morning when RH near the surface is high and NO3 radical chemistry is competitive with O3 and OH reactions. However, observations of the effect of water on SOA formation originating from NO3 oxidation hint at a varied role. Spittler et al. (2006) reported lower SOA yields under humid conditions, but other studies did not observe a significant effect (Bonn and Moortgat, 2002; Fry et al., 2009; Boyd et al., 2015). Among the important effects of water is its role as a medium for hydrolysis. In laboratory studies, primary and secondary organic nitrates were found to be less prone to aqueous hydrolysis than tertiary organic nitrates (Darer et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2011). First-generation organic nitrates retaining double bonds may also hydrolyze relatively quickly, especially in the presence of acidity (Jacobs et al., 2014; Rindelaub et al., 2015). Depending on the relative amount of these different types of organic nitrates, the overall hydrolysis rate could be different for organic nitrates formed from NO3 oxidation and photooxidation in the presence of NOx (Boyd et al., 2015). Recently, there has been increasing evidence from field measurements that organic nitrates hydrolyze in the particle phase, producing HNO3 (Liu et al., 2012b; Browne et al., 2013). This has been only a limited focus of chamber experiments to date (Boyd et al., 2015). In addition to the effect of RH, particle-phase acidity is known to affect SOA formation from ozonolysis and OH reaction (e.g., Gao et al., 2004; Tolocka et al., 2004). Thus far, only one study has examined the effect of acidity on NO3-initiated SOA formation and found a negligible effect (Boyd et al., 2015). Notably, an effect of acidity was observed for the hydrolysis of organic nitrates produced in photochemical reactions (Szmigielski et al., 2010; Rindelaub et al., 2015). While much organic nitrate aerosol is formed via NO3+ BVOC reactions, some fraction can also form from RO2+ NO chemistry. Rollins et al. (2010) observed the organic nitrate moiety in 6–15 % of total SOA mass generated from high-NOx photooxidation of limonene, α-pinene, Δ3-carene, and tridecane. A very recent study of Berkemeier et al. (2016) showed that organic nitrates accounted for ~ 40 % of SOA mass during initial particle formation in α-pinene oxidation by O3 in the presence of NO, decreasing to ~ 15 % upon particle growth to the accumulation-mode size range. They also observed a tight correlation (R2 = 0.98) between organic nitrate content and SOA particle number concentrations. This implies that organic nitrates may be among the extremely low volatility organic compounds (ELVOC) (Ehn et al., 2014; Tröstl et al., 2016) that play a critical role in nucleation and nanoparticle growth.

2.3 Heterogeneous and aqueous-phase NO3 processes

The NO3 radical is not only a key nighttime oxidant of organic (and especially biogenic) trace gases but it can also play an important role in the aqueous phase of tropospheric clouds and deliquesced particles (Chameides, 1978; Wayne et al., 1991; Herrmann and Zellner, 1998; Rudich et al., 1998). Whilst the reaction of NO3 with organic particles and aqueous droplets in the atmosphere is believed to represent only an insignificant fraction of the overall loss rate for NO3, it can have a substantial impact on the chemical and physical properties of the particle by modifying its lifetime, oxidation state, viscosity, and hygroscopic properties and thus its propensity to act as a cloud condensation nucleus (Rudich, 2003).

Biogenic VOC include, but are not limited to the isoprenoids (isoprene, mono-, and sesquiterpenes) as well as alkanes, alkenes, carbonyls, alcohols, esters, ethers, and acids (Kesselmeier and Staudt, 1999). Recent measurements indicate that biogenic emissions of aromatic trace gases are also significant (Misztal et al., 2015). The gas-phase degradation of BVOC leads to the formation of a complex mixture of organic trace gases including hydroxyl- and nitrate-substituted oxygenates which can transfer to the particle phase by condensation or dissolution. Our present understanding is that non-anthropogenic SOA has a large contribution from isoprenoid degradation.

As is generally the case for laboratory studies of heterogeneous processes, most of the experimental investigations on heterogeneous uptake of NO3 to organic surfaces have dealt with single-component systems that act as surrogates for the considerably more complex mixtures found in atmospheric SOA. A further level of complexity arises when we consider that initially reactive systems, e.g., containing condensed or dissolved unsaturated hydrocarbons, can become deactivated as SOA ages, single bonds replace double bonds, and the oxygen-to-carbon ratio increases.

We summarize the results of the laboratory studies to provide a rough guide to NO3 reactivity on different classes of organics which may be present in SOA and note that further studies of NO3 uptake to biogenic SOA which was either generated and aged under well-defined conditions (Fry et al., 2011) or sampled from the atmosphere are required to confirm predictions of uptake efficiency based on the presently available database.

2.3.1 Heterogeneous processes

For some particle-phase organics, the reaction with NO3 is at least as important as other atmospheric oxidants such as O3 and OH (Shiraiwa et al., 2009; Kaiser et al., 2011). The lifetime (τ) of a single component, liquid organic particle with respect to loss by reaction with NO3 at concentration [NO3] is partially governed by the uptake coefficient (γ) (Robinson et al., 2006; Gross et al., 2009):

| (1) |

where Dp is the particle diameter, ρorg and Morg are the density and molecular weight of the organic component, respectively, c̄ is the mean molecular velocity of gas-phase NO3, and NA is Avogadro number. Thus, defined, τ is the time required for all the organic molecules in a spherical (i.e., liquid) particle to undergo a single reaction with NO3.

Recent studies have shown that organic aerosols can adopt semi-solid (highly viscous) or amorphous solid (crystalline or glass) phase states, depending on the composition and ambient conditions (Virtanen et al., 2010; Koop et al., 2011; Renbaum-Wolff et al., 2013). Typically, the bulk phase diffusion coefficients of NO3 are ~ 10−7–10−9 cm2 s−1 in semi-solid and ~ 10−10 cm2 s−1 in solids (Shiraiwa et al., 2011). Slow bulk diffusion of NO3 in a viscous organic matrix can effectively limit the rate of uptake (Xiao and Bertram, 2011; Shiraiwa et al., 2012). Similarly, the solubility may be different in a concentrated, organic medium. If bulk diffusion is slow, the reaction may be confined to the near-surface layers of the particle or bulk substrate. The presence of organic coatings on aqueous aerosols was found to suppress heterogeneous N2O5 hydrolysis by providing a barrier through which N2O5 needs to diffuse to undergo hydrolysis (Alvarado et al., 1998; Cosman et al., 2008; Grifiths et al., 2009). Reactive uptake by organic aerosols is expected to exhibit a pronounced decrease at low RH and temperature, owing to a phase transition from viscous liquid to semi-solid or amorphous solid (Arangio et al., 2015). Therefore, the presence of a semi-solid matrix may effectively shield reactive organic compounds from chemical degradation in long-range transport in the free troposphere.

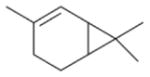

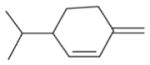

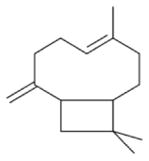

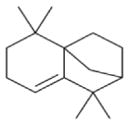

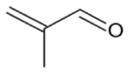

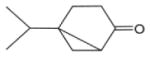

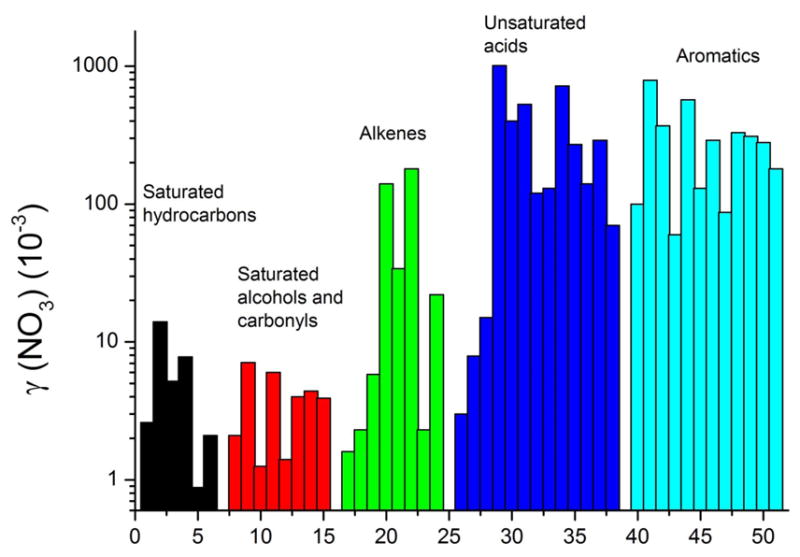

To get an estimate of the processing rate of BVOC-derived SOA, we have summarized the results of several laboratory studies to provide a rough guide to NO3 reactivity on different classes of organics that may be present in SOA (Fig. 3). A rough estimate of the reactivity of NO3 to freshly generated, isoprenoid-derived SOA, which still contains organics with double bonds (e.g., from diolefinic monoterpenes such as limonene), may be obtained by considering the data on alkenes and unsaturated acids, where the uptake coefficient is generally close to 0.1.

Figure 3.

Uptake coefficients, γ (NO3), for the interaction of NO3 with single-component organic surfaces. Details of the experiments and the references (corresponding to the x-axis numbers) are given in Table S1 in the Supplement.

The classes of organics for which heterogeneous reactions with NO3 have been examined are alkanoic/alkenoic acids, alkanes and alkenes, alcohols, aldehydes, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and secondary organic aerosols. Laboratory studies have used either pure organic substrates, with the organic of interest internally mixed in an aqueous particle; as a surface coating, with the reactive organic mixed in a nonreactive organic matrix; or in the form of self-assembling monolayers. The surrogate surface may be available as a macroscopic bulk liquid (or frozen liquid) or in particulate form and both gas-phase and particle-phase analyses have been used to derive kinetic parameters and investigate products formed.

In the gas phase, the NO3 radical reacts slowly (by H-abstraction) with alkanes, more rapidly with aldehydes due to the weaker C-H bond of the carbonyl group, and most readily with alkenes and aromatics via electrophilic addition. This trend in reactivity is also observed in the condensed-phase reactions of NO3 with organics so that long-chain organics, for which non-sterically hindered addition to a double bond is possible, and aromatics are the most reactive. In very general terms, uptake coefficients are in the range of 1–10 × 10−3 for alkanes, alcohols, and acids without double bonds, 2–200 × 10−3 for alkenes with varying numbers of double bonds, 3–1000 × 10−3 for acids with double bonds again depending on the number of double bonds, and 100–500 × 10−3 for aromatics. These trends are illustrated in Fig. 3 which plots the experimental data for the uptake of NO3 to single-component organic surfaces belonging to different classes of condensable organics. Condensed-phase organic nitrates have been frequently observed following interaction of NO3 with organic surfaces (see below).

Saturated hydrocarbons

Uptake of NO3 to saturated hydrocarbons is relatively slow, with uptake coefficients close to 10−3. Moise et al. (2002) found that (for a solid sample) uptake to a branched-chain alkane was more efficient than for a straight-chain alkane, which is consistent with known trends in gas-phase reactivity of NO3. The slow surface reaction with alkanes enables both surface and bulk components of the reaction to operate in parallel. The observation of RONO2 as product is explained (Knopf et al., 2006; Gross and Bertram, 2009) by processes similar to those proceeding in the gas phase, i.e., abstraction followed by formation of peroxy and alkoxy intermediates which react with NO2 and NO3 to form the organic nitrate.

Unsaturated hydrocarbons

With exception of the data of Moise et al. (2002), the up-take of NO3 to an unsaturated organic surface is found to be much more efficient than to the saturated analogue. The NO3 uptake coefficient for, e.g., squalene, is at least an order of magnitude more efficient than for squalane (Xiao and Bertram, 2011; Lee et al., 2013). The location of the double bond is also important and the larger value for γ found for a self-assembling monolayer of NO3+ undec-10-ene-1-thiol compared to liquid, long-chain alkenes is due to the fact that the terminal double bond is located at the interface and is thus more accessible for a gas-phase reactant (Gross and Bertram, 2009). NO3 uptake to mixtures of unsaturated methyl oleate in a matrix of saturated organic was found to be consistent with either a surface or bulk reaction (Xiao and Bertram, 2011). The formation of condensed-phase organic nitrates and simultaneous loss of the vinyl group indicates that the reaction proceeds, as in the gas phase, by addition of NO3 to the double bond followed by reaction of NO3 (or NO2) with the resulting alkyl and peroxy radicals formed (Zhang et al., 2014b).

Saturated alcohols and carbonyls

Consistent with reactivity trends for NO3 in the gas phase, the weakening of some C-H bonds in oxidized, saturated organics results in a more efficient interaction of NO3 than for the non-oxidized counterparts although, as far as the limited dataset allows trends to be deduced, the gas-phase reactivity trend of polyalcohol being greater than alkanoate appears to be reversed in the liquid phase (Gross et al., 2009). For multicomponent liquid particles, the uptake coefficient will also depend on the particle viscosity (Iannone et al., 2011) though it has not been clearly established if the reaction proceeds predominantly at the surface or throughout the particle (Iannone et al., 2011). The reaction products are expected to be formed via similar pathways as seen in the gas phase, i.e., abstraction of the aldehydic-H atom for aldehydes and abstraction of an H atom from either the O-H or adjacent α-CH2 group for alcohols prior to reaction of NO2 and NO3 with the ensuing alkyl and peroxy radicals (Zhang and Morris, 2015).

Organic acids

The efficiency of uptake of NO3 to unsaturated acids is comparable to that found with other oxidized, saturated organics (Moise et al., 2002) suggesting that the reaction proceeds, as in the gas phase, via abstraction rather than addition. Significantly larger uptake coefficients have been observed for a range of unsaturated, long-chain acids, with γ often between 0.1 and 1 (Gross et al., 2009; Knopf et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011a). γ depends on the number and position (steric factors) of the double bond. For example, the uptake coefficient for abietic acid is a factor of 100 lower than for linoleic acid (Knopf et al., 2011). The condensed-phase products formed in the interaction of NO3 with unsaturated acids are substituted carboxylic acids, including hydroxy nitrates, carbonyl nitrates, dinitrates, and hydroxy dinitrates (Hung et al., 2005; Docherty and Ziemann, 2006; McNeill et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2011a).

Aromatics

The interaction of NO3 with condensed-phase aromatics and PAHs results in the formation of a large number of nitrated aromatics and nitro PAHs. Similar to the gas-phase mechanism, the reaction is initiated by addition of NO3 to the aromatic ring, followed by breaking of an N-O bond to release NO2 to the gas phase and forming a nitrooxy-cyclohexadienyl-type radical which can further react with O2, NO2, or undergo internal rearrangement to form hydroxyl species (Gross and Bertram, 2008; Lu et al., 2011). The uptake coefficients are large and comparable to those derived for the unsaturated fatty acids.

The literature results on the interaction of NO3 with organic substrates are tabulated in Table S1 in the Supplement, in which the uptake coefficient is listed (if available) along with the observed condensed- and gas-phase products.

2.3.2 Aqueous-phase reactions

The in situ formation of NO3 (e.g., electron transfer reactions between nitrate anions and other aqueous radical anions such as , sulfur-containing radical anions, or ) is generally of minor importance and the presence of NO3 in aqueous particles is largely a result of transfer from the gas phase (Herrmann et al., 2005; Tilgner et al., 2013). Concentrations of NO3 in tropospheric aqueous solutions cannot be measured in situ, and literature values are based on multiphase model predictions (Herrmann et al., 2010). Model studies with the chemical aqueous-phase radical mechanism (CAPRAM; Herrmann et al., 2005; Tilgner et al., 2013) predict [NO3] between 1 × 6 × 10−16 and 2.7 × 10−13 mol L−1. High NO3 concentration levels are associated with urban clouds, while in rural and marine clouds these levels are an order of magnitude lower. Since the NO3 concentrations are related to the NOx budget, typically higher NO3 concentrations are present under urban cloud conditions compared to rural and marine cloud regimes.

NO3 radicals react with dissolved organic species via three different pathways: (i) by H-atom abstraction from saturated organic compounds, (ii) by electrophilic addition to double bonds within unsaturated organic compounds, and (iii) by electron transfer from dissociated organic acids (Huie, 1994; Herrmann and Zellner, 1998). For a detailed overview on aqueous-phase NO3 radical kinetics, the reader is referred to several recent summaries (Neta et al., 1988; Herrmann and Zellner, 1998; Ross et al., 1998; Herrmann, 2003; Herrmann et al., 2010, 2015). Compared to the highly reactive and non-selective OH radical, the NO3 radical is characterized by a lower reactivity and represents a more selective aqueous-phase oxidant. The available kinetic data indicate that the reactivity of NO3 radicals with organic compounds in comparison to the two other key radicals (OH, ) is as follows: (Herrmann et al., 2015).

In Table S2, we list kinetic parameters for reaction of NO3 with aliphatic organic compounds as presently incorporated in the CAPRAM database (Bräuer et al., 2017). Typical ranges of rate constants (in M−1 s−1) for reactions of NO3 in the aqueous phase are 106–107 for saturated alcohols, carbonyls, and sugars; 104–106 for protonated aliphatic mono- and dicarboxylic acids, with higher values for oxygenated acids; 106–108 for deprotonated aliphatic mono- and dicarboxylic acids (higher values typically for oxygenated acids); 107–109 for unsaturated aliphatic compounds; and 108–2 × 109 for aromatic compounds (without nitro/acid functionality). The somewhat larger rate constants for deprotonated aliphatic mono- and dicarboxylic acids, unsaturated aliphatic compounds and aromatic compounds is related to the occurrence of electron transfer reactions and addition reaction pathways, which are often faster than H-abstraction reactions.

Many aqueous-phase NO3 reaction rate constants, even for small oxygenated organic compounds, are not available in the literature and have to be estimated. In the absence of SARs for NO3 radical reactions with organic compounds, Evans–Polanyi-type reactivity correlations are used to predict kinetic data for H-abstraction NO3 radical reactions. The latest correlation for NO3 reactions in aqueous solution based on 38 H-abstraction reactions of aliphatic alcohols, carbonyl compounds and carboxylic acids was published by Hoffmann et al. (2009):

| (2) |

where BDE is the bond dissociation energy (in kJ mol−1). The correlation is quite tight, with a correlation coefficient of R = 0.9.

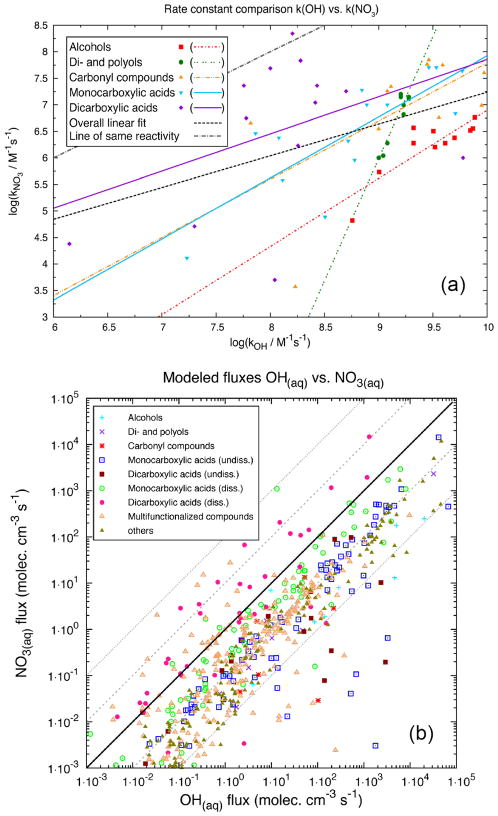

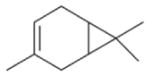

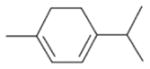

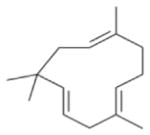

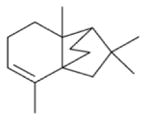

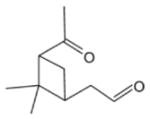

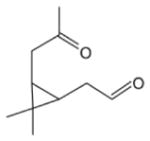

A direct comparison of the aqueous-phase OH and NO3 radical rate constants (k298 K) of organic compounds from different compound classes is presented in Fig. 4, which shows that the NO3 radical reaction rate constants for many organic compounds are about 2 orders of magnitude smaller than respective OH rate constants. In contrast, deprotonated dicarboxylic acids can react with NO3 via electron transfer and have similar rate constants for OH reaction. Rate constants for OH and NO3 with alcohols and diols/polyols are well correlated (R2 values are given in Table S3), whereas those rate constants for carbonyl compounds and diacids have a lower degree of correlation.

Figure 4.

(a) Correlation of OH versus NO3 radical rate constants in the aqueous phase for the respective compound classes. The linear regression fits for the different compound classes are presented in the same color as the respective data points. The black line represents the correlation of the overall data. (b) Comparison of modeled, aqueous-phase reaction fluxes (mean chemical fluxes in mol cm−3 s−1 over a simulation period of 4–5 days) of organic compounds with hydroxyl (OH) versus nitrate (NO3) radicals distinguished by different compound classes (urban CAPRAM summer scenario).

Figure 4b shows a comparison of the modeled chemical turnovers of reactions of organic compounds with OH versus NO3 radicals distinguished for different compound classes. The simulations were performed with the SPACCIM model (Wolke et al., 2005) for the urban summer CAPRAM scenario (see Tilgner et al., 2013 for details) using the master chemical mechanism (MCM) 3.2/CAPRAM 4.0 mechanism (Rickard, 2015; Bräuer et al., 2017) which has in total 862 NO3 radical reactions with organic compounds.

Most of the data lie under the 1 : 1 line, indicating that, for most of the organic compounds considered, chemical degradation by OH is more important than by NO3, with a significant fraction of the data lying close to a 10 : 1 line, though OH fluxes sometimes exceed NO3 fluxes by a factor of 103 – 104. Approximate relative flux ratios (NO3 / OH) for different classes of organic are 10−1 – 10−2 for alcohols (including diols and polyols) and carbonyl compounds, 10−1 – 10−4 for undissociated monoacids and diacids, ~ 1 (or larger) for dissociated monoacids, 10−2 – > 10 for dissociated diacids, and 10−2–1 for organic nitrates. For carboxylate ions, NO3-initiated electron transfer is thus the dominant oxidation pathway. As OH-initiated oxidation proceeds via an H-abstraction, high NO3-OH flux ratios can be observed for carboxylate ions but not for protonated carboxylic acids.

Overall, Fig. 4b shows that, over a 4-day summer cycle, NO3 radical reactions can compete with OH radical reactions in particular for protonated carboxylic acids and multifunctional compounds. Nevertheless, aqueous NO3 radical reactions with organics will become more important during winter or at higher latitudes, where photochemistry as the main source of OH is less important. Finally, it should be noted that NO3 aqueous-phase nighttime chemistry will influence the concentration levels of many aqueous-phase reactants available for reaction during the next day.

2.4 Instrumental methods

Atmospheric models of the interaction of NO3 with BVOC rely on experimental data gathered in both the laboratory and the field. These experimental data are used to define model parameters and to evaluate model performance by comparison to observed quantities. Instrumentation for measurements of nitrogen-containing species, oxidants, and organic compounds, including NOx, O3, NO3, BVOC, and oxidized reactive nitrogen compounds, are all important to understand the processes at work. Of particular importance to the subject of this review is the characterization of organic nitrates, which are now known to exist in both the gas and particle phases and whose atmospheric chemistry is complex. This section reviews historical and current experimental methods used for elucidating NO3-BVOC atmospheric chemistry.

2.4.1 Nitrate radical measurements

Optical absorption spectroscopy has been the primary measurement technique for NO3. It usually makes use of two prominent absorption features of NO3 near 623 and 662 nm. Note that the dissociation limit of the NO3 molecule lies between the two absorption lines (Johnston et al., 1996); thus, illumination by measurement radiation at the longer wave-length band does not lead to photolysis of NO3. The room temperature absorption cross section of NO3 at 662 nm is ~ 2 × 10−17 cm2 molec−1 and increases at lower temperature (Yokelson et al., 1994; Osthoff et al., 2007). Thus, at a typical minimum detectable optical density (reduction of the intensity compared to no absorption) and a light-path length of 5 km, a detection limit of 107 molec cm−3 or ~ 0.4 ppt (under standard conditions) is achieved.

Initial measurements of NO3 in the atmosphere were long-path averages using light paths between either the sun or the moon (e.g., Noxon et al., 1978) and the receiving spectrometer (also called passive techniques because natural light sources were used) or between an artificial light source and spectrometer over a distance of several kilometers (active techniques; e.g., Platt et al., 1980). Passive techniques were later extended to yield NO3 vertical profiles (e.g., Weaver et al., 1996). In recent years, resonator cavity techniques allowed construction of very compact instruments capable of performing in situ measurements of NO3 with absorption spectroscopy (see in situ measurement techniques below).

An important distinction between the techniques is whether NO3 can be deliberately or inadvertently removed from the absorption path as part of the observing strategy. Long-path absorption spectroscopy does not allow control over the sample for obtaining a zero background by removing NO3 (Category 1). Resonator techniques (at least as long as the resonator is encased) allow deliberate removal of NO3 from the absorption path as part of the measurement sequence and may also result in inadvertent removal during sampling (Category 2).

For instruments of Category 1, the intensity without absorber (I0) cannot be easily detected. Therefore, the information about the absorption due to NO3 (and any other trace gas) has to be determined from the structure of the absorption, which is usually done by using differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) (Platt and Stutz, 2008), which relies on the characteristic fingerprint of the NO3 absorption structure in a finite wavelength range (about several 10 nm wide). Thus, a spectrometer of sufficient spectral range and resolution (around 0.5 nm) is required.

Instruments of Category 2 can determine the NO3 concentration from the difference (or rather log of the ratio) of the intensity with and without NO3 in the measurement volume. In this case, only an intensity measurement at a single wavelength (typically of a laser) is necessary, and specificity can be achieved through chemical titration with NO (Brown et al., 2001). However, enhanced specificity without chemical titration can be gained by combining resonator techniques with DOAS detection. It should be noted that the advantage of a closed cavity to be able to remove (or manipulate) NO3 comes at the expense of potential wall losses, which have to be characterized. Such instruments have the advantage of being able to also detect N2O5, which is in thermal equilibrium with NO3 and can be quantitatively converted to NO3 by thermal dissociation (Brown et al., 2001, 2002).

Another complication arises from the presence of water vapor and oxygen lines in the wavelength range of strong NO3 absorptions. To compensate for these potential interferences in open-path measurements (where NO3 cannot easily be removed), daytime measurements are frequently used as reference because NO3 levels are typically very low (but not necessarily negligibly low) (Geyer et al., 2003). Thus, a good fraction of the reported NO3 data (in particular, older data) represents day–night differences.

Passive long-path remote sensing techniques

Measurements of the NO3 absorption structure using sunlight take advantage of the fact that NO3 is very quickly photolyzed by sunlight (around 5 s lifetime during the day) allowing for vertically resolved measurements during twilight (e.g., Aliwell and Jones, 1998; Allan et al., 2002; Coe et al., 2002; von Friedeburg et al., 2002). The fact that the NO3 concentration is nearly zero due to rapid photolysis in the directly sunlit atmosphere, while it is largely undisturbed in a shadowed area, can be used to determine NO3 vertical concentration profiles during sunrise using the moon as a light source (Smith and Solomon, 1990; Smith et al., 1993; Weaver et al., 1996). Alternatively, the time series of the NO3 column density derived from scattered sunlight originating from the zenith (or from a viewing direction away from the sun) during sunrise can be evaluated to yield NO3 vertical profiles (Allan et al., 2002; Coe et al., 2002; von Friedeburg et al., 2002).

Nighttime NO3 total column data have been derived by spectroscopy of moonlight and starlight (Naudet et al., 1981), the intensity of which is about 4–5 orders of magnitude lower than that of sunlight. Thus, photolysis of NO3 by moonlight is negligible. A series of moonlight NO3 measurements have been reported (Noxon et al., 1980; Noxon, 1983; Sanders et al., 1987; Solomon et al., 1989, 1993; Aliwell and Jones, 1996a, b; Wagner et al., 2000). These measurements yield total column data of NO3, the sum of tropospheric and stratospheric partial columns. Separation between stratospheric and tropospheric NO3 can be accomplished (to some extent) by the Langley plot method (Noxon et al., 1980), which takes advantage of the different dependence of tropospheric and stratospheric NO3 slant column density on the lunar zenith angle.

Active long-path techniques

A large number of NO3 measurements have been made using the active long-path DOAS technique (Platt et al., 1980, 1981, 1984; Pitts et al., 1984; Heintz et al., 1996; Allan et al., 2000; Martinez et al., 2000; Geyer et al., 2001a, b, 2003; Gölz et al., 2001; Stutz et al., 2002, 2004, 2010; Asaf et al., 2009; McLaren et al., 2010; Crowley et al., 2011; Sobanski et al., 2016). Here, a searchlight-type light source is used to transmit a beam of light across a kilometer-long light path in the open atmosphere to a receiving telescope–spectrometer combination. The light source typically is a broadband thermal radiator (incandescent lamp, Xe arc lamp, laser-driven light source). More recently, LED light sources were also used (Kern et al., 2006). The telescope (around 0.2 m diameter) collects the radiation and transmits it, usually through an optical fiber, into the spectrometer, which produces the absorption spectrum. Modern instruments now almost exclusively use transmitter/receiver combinations at one end of the light path and retro-reflector arrays (e.g., cat-eye-like optical devices) at the other end. The great advantage of this approach is that power and optical adjustment is only required at one end of the light path while the other end (with the retro-reflector array) is fixed. In this way, several retro-reflector arrays, for instance, mounted at different altitudes, can be used sequentially with the same transmitter/receiver unit allowing determination of vertical profiles of NO3 (and other species measurable by DOAS) (Stutz et al., 2002, 2004, 2010).

In situ measurement techniques

Cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) and cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy (CEAS) are related techniques for in situ quantification of atmospheric trace gases such as NO3. These methods are characterized by high sensitivity, specificity, and acquisition speed (Table 3a), and they allow for spatially resolved measurements on mobile platforms.

Table 3.

(a)Selected CRDS and CEAS instruments used to quantify NO3 mixing ratios in ambient air. (b) Selected instruments used to quantify NO3 and N2O5 mixing ratios in ambient air other than by cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy.

| (a)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Principle of measurement (laser pulse rate) | LOD or precision (integration time) | Reference |

| BB-CEAS | 2.5 pptv (8.6 min) | Ball et al. (2004) |

| BB-CRDS | 1 pptv (100 s) | Bitter et al. (2005) |

| Off-axis cw CRDS (500 Hz) | 2 pptv (5 s) | Ayers and Simpson (2006) |

| On-axis pDL-CRDS (33 Hz) | <1 pptv (1 s) | Dubé et al. (2006) |

| BB-CEAS | 4 pptv (60 s) | Venables et al. (2006) |

| pDL-CRDS (10 Hz) | 2.2 pptv (100 s) | Nakayama et al. (2008) |

| Off-axis cw CRDS (200 Hz) | 2 pptv (5 s) | Schuster et al. (2009), Crowley et al. (2010) |

| CE-DOAS | 6.3 pptv (300 s) | Platt et al. (2009), Meinen et al. (2010) |

| BB-CEAS | 2 pptv (15 s) | Langridge et al. (2008), Benton et al. (2010) |

| BB-CEAS | < 2 pptv (1s) | Kennedy et al. (2011) |

| On-axis cw-CRDS (500 Hz) | <1 pptv (1 s) | Wagner et al. (2011) |

| On-axis cw-CRDS (300 Hz) | 8 pptv (10 s) | Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff (2011) |

| BB-CEAS | 1 pptv (1 s) | Le Breton et al. (2014) |

| BB-CEAS | 7.9 pptv (60 s) | Wu et al. (2014) |

| (b)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle of measurement | LOD or precision e(integration time) | Species detected | Reference |

| MIESR | < 2 pptv (30 min) | NO3 | Geyer et al. (1999) |

| CIMS | 12 pptv (1 s) | NO3 + N2O5 | Slusher et al. (2004) |

| LIF | 11 pptv (10 min) | NO3 | Matsumoto et al. (2005a), Matsumoto et al. (2005b) |

| LIF | 28 pptv (10 min) | NO3 | Wood et al. (2005) |

| CIMS | 30 pptv (30 s) | N2O5 | Zheng et al. (2008) |

| CIMS | 5 pptv (1 min) | N2O5 | Kercher et al. (2009) |

| CIMS | 7.4 pptv (1 s) | N2O5 | Le Breton et al. (2014) |

| CIMS | 39 pptv (6 s) | N2O5 | Wang et al. (2014) |

CEAS = cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy; CRDS = cavity ring-down spectroscopy; BB = broadband; pDL = pulsed dye laser; CE-DOAS = cavity-enhanced differential optical absorption spectroscopy; cw = continuous-wave diode laser. MIESR = matrix isolation electron spin resonance; CIMS = chemical ionization mass spectrometry; LIF = laser-induced fluorescence; LOD = limit of detection.

In CRDS, laser light is “trapped” in a high-finesse stable optical cavity, which usually consists of a pair of highly reflective spherical mirrors in a near-confocal arrangement. The concentrations of the optical absorbers present within the resonator are derived from the Beer–Lambert law and the rate of light leaking from the cavity after the input beam has been switched off (O’Keefe and Deacon, 1988). CRDS instruments are inherently sensitive as they achieve long effective optical absorption paths (up to, or in some cases exceeding, 100 km) as the light decay is monitored for several 100 μs, and the absorption measurement is not affected by laser intensity fluctuations. For detection of NO3 at 662 nm, pulsed laser sources such as Nd:YAG pumped dye lasers have been used because of the relative ease of coupling the laser beam to the optical cavity (Brown et al., 2002, 2003; Dubé et al., 2006). Relatively lower cost continuous-wave (cw) diode laser modules that are easily modulated also have been popular choices (e.g., King et al., 2000; Simpson, 2003; Ayers et al., 2005; Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff, 2011; Wagner et al., 2011).

In a CEAS instrument (also referred to as integrated cavity output spectroscopy, ICOS, or cavity-enhanced DOAS, CE-DOAS), the spectrum transmitted through a high-finesse optical cavity is recorded. Mixing ratios of the absorbing gases are derived using spectral retrieval routines similar to those used for open-path DOAS (e.g., O’Keefe, 1998, 1999; Ball et al., 2001; Fiedler et al., 2003; Platt et al., 2009; Schuster et al., 2009).

CRDS and CEAS are, in principle, absolute measurement techniques and do not need to rely on external calibration. In practice, however, chemical losses can occur on the inner walls of the inlet (even when constructed from inert materials such as Teflon) or at the aerosol filters necessary for CRDS instruments. Hence, the inlet transmission efficiencies have to be monitored for measurements to be accurate (Fuchs et al., 2008, 2012; Odame-Ankrah and Osthoff, 2011). On the other hand, a key advantage of in situ instruments over open-path instruments is that the sampled air can be manipulated. Deliberate addition of excess NO to the instrument’s inlet titrates NO3 and allows measurement of the instrument’s zero level and separation of contributions to optical extinction from other species, such as NO2, O3, and H2O. Adding a heated section to the inlet (usually in a second detection channel) enables (parallel) detection of N2O5 via the increase in the NO3 signal (Brown et al., 2001; Simpson, 2003).

In addition, non-optical techniques have been used to detect and quantify NO3. Chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS) is a powerful method for sensitive, selective, and fast quantification of a variety of atmospheric trace gases (Huey, 2007). NO3 is readily detected after reaction with iodide reagent ion as the nitrate anion at m/z 62; at this mass, however, there are several known interferences, including dissociative generation from N2O5, HNO3, and HO2NO2 (Slusher et al., 2004; Abida et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). There has been more success with the quantification of N2O5, usually as the iodide cluster ion at m/z 235 (Kercher et al., 2009), though accurate N2O5 measurement at m/z 62 has been reported from recent aircraft measurements with a large N2O5 signal (Le Breton et al., 2014).

Two groups have used laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) to quantify NO3 (and N2O5 through thermal dissociation) in ambient air (Wood et al., 2003; Matsumoto et al., 2005a, b). The major drawback of this method is the relatively low fluorescence quantum yield of NO3, and hence the method has not gained wide use.

Another technique that was demonstrated to be capable of measuring NO3 radicals at atmospheric concentration is matrix isolation electron spin resonance (MIESR) (Geyer et al., 1999). Although the technique allows simultaneous detection of other radicals (including HO2 and NO2), it has not been used extensively, probably because of its complexity.

Recently, a variety of in situ NO3 (Dorn et al., 2013) and N2O5 (Fuchs et al., 2012) measurement techniques were compared at the SAPHIR chamber in Jülich, Germany. All instruments measuring NO3 were optically based (absorption or fluorescence). N2O5 was detected as NO3 after thermal decomposition in a heated inlet by either CRDS or LIF. Generally, agreement within the accuracy of instruments was found for all techniques detecting NO3 and/or N2O5 in this comparison exercise. This study showed excellent agreement between the instruments on the single-digit ppt NO3 and N2O5 levels with no noticeable interference due to NO2 and water vapor for instruments based on cavity ring-down or cavity-enhanced spectroscopy. Because of the low sensitivity of LIF instruments, N2O5 measurements by these instruments were significantly noisier compared to the measurements by cavity-enhanced methods. The agreement between instruments was less good in experiments with high aerosol mass loadings, specifically for N2O5, presumably due to enhanced, unaccounted loss of NO3 and N2O5 demonstrating the need for regular filter changes in closed-cavity instruments. Whereas differences between N2O5 measurements were less than 20 % in the absence of aerosol, measurements differed up to a factor of 2.5 for the highest aerosol surface concentrations of 5 × 108 nm2 cm−3. Also, differences between NO3 measurements showed an increasing trend (up to 50 %) with increasing aerosol surface concentration for some instruments.

2.4.2 Gas-phase organic nitrate measurements

Analytical techniques to detect gaseous organic nitrates have been documented in a recent review by Perring et al. (2013). Sample collection techniques for organic nitrates include preconcentration on solid adsorbents (Atlas and Schauffler, 1991; Schneider and Ballschmiter, 1999; Grossenbacher et al., 2001), cryogenic trapping (Flocke et al., 1991) or collection in stainless steel canisters (Flocke et al., 1998; Blake et al., 1999), or direct sampling (Day et al., 2002; Beaver et al., 2012).

The approaches to the analysis of the organic nitrates fall into three broad categories. First, one or more chemically speciated organic nitrates are measured by a variety of techniques including liquid chromatography (LC) (Kastler et al., 2000) or gas chromatography (GC) with electron capture detection (Fischer et al., 2000), GC with electron impact or negative-ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Atlas, 1988; Luxenhofer et al., 1996; Blake et al., 1999, 2003a, b; Worton et al., 2008), GC followed by conversion to NO and chemiluminescent detection (Flocke et al., 1991, 1998), GC followed by photoionization mass spectrometry (Takagi et al., 1981), GC followed by conversion of organic nitrates to NO2 and luminol chemiluminescent detection (Hao et al., 1994), CIMS (Beaver et al., 2012; Paulot et al., 2012), and proton transfer reaction MS (PTR-MS) (Perring et al., 2009). Second, the sum of all organic nitrates can be measured directly by thermal dissociation to NO2, which is subsequently measured by LIF (TD-LIF) (Day et al., 2002), CRDS (TD-CRDS) (Paul et al., 2009; Thieser et al., 2016), or cavity-attenuated phase shift spectroscopy (TD-CAPS) (Sadanaga et al., 2016). Finally, the sum of all organic nitrates can be measured indirectly as the difference between all reactive NOx except for organic nitrates and total oxidized nitrogen (NOy ) (Parrish et al., 1993).

Recent advances in adduct ionization utilize detection of the charged cluster of the parent reagent ion with the compound of interest. This scheme is then coupled to high-resolution time-of-flight (HR-ToF) mass spectrometry. The combination of these methods allows the identification of molecular composition due to the soft ionization approach that minimizes fragmentation. Multifunctional organic nitrates resulting from the oxidation of BVOC have been detected using CF3O− (Bates et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2015; Schwantes et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2015) and iodide as reagent ions (Lee et al., 2014a, 2016; Xiong et al., 2015, 2016; Nah et al., 2016b).

2.4.3 Online analysis of particulate matter