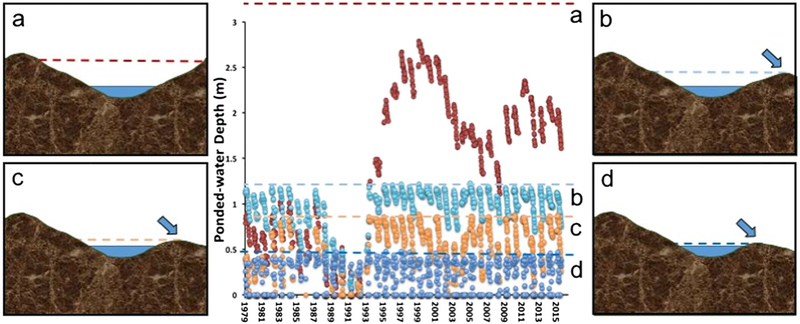

Fig. 1.

Little knowledge about magnitude and timing of surface-water connectivity is gained by knowing that a wetland is surrounded by upland, i.e., is “geographically isolated.” The above hydrograph displays water levels of four “geographically isolated” prairie-pothole wetlands (labeled a–d) at the Cottonwood Lake Study Area in Stutsman County, North Dakota, over a 36-year period (1979–2015). The drawings on the left and right of the hydrograph characterize the upland-embedded basins of the wetlands. External spill points (arrows), as defined by Leibowitz et al. (2016), set limits (color-coded dashed lines) to water storage and thus the magnitude of water losses from these wetland basins. Wetland P1 (a) is situated within a deep basin that does not have a realized external spill-point and thus does not contribute (i.e., spill) to down-gradient surface-water flows. By contrast, wetlands P8 (b), P3 (c), and T6 (d) each, to varying degrees, contribute to down-gradient flows when water levels reach an external spill point. The magnitude and timing of these surface-water flows vary greatly with similarly variable hydrological, geochemical and ecological effects