Abstract

Background

Although childhood adversity is a potent determinant of psychopathology, relatively little is known about how the characteristics of adversity exposure, including its developmental timing or duration, influence subsequent mental health outcomes. This study compared three models from life course theory (recency, accumulation, sensitive period) to determine which one(s) best explained this relationship.

Methods

Prospective data came from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC; n=7,476). Four adversities commonly linked to psychopathology (caregiver physical/emotional abuse; sexual/physical abuse; financial stress; parent legal problems) were measured repeatedly from birth to age eight. Using a statistical modeling approach grounded in least angle regression, we determined the theoretical model(s) explaining the most variability (r2) in psychopathology symptoms measured at age 8 using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and evaluated the magnitude of each association.

Results

Recency was the best fitting theoretical model for the effect of physical/sexual abuse (girls r2=2.35%; boys r2=1.68%). Both recency (girls r2=1.55%) and accumulation (boys r2=1.71%) were the best fitting models for caregiver physical/emotional abuse. Sensitive period models were chosen alone (parent legal problems in boys r2=0.29%) and with accumulation (financial stress in girls r2=3.08%) more rarely. Substantial effect sizes were observed (standardized mean differences=0.22–1.18).

Conclusions

Child psychopathology symptoms are primarily explained by recency and accumulation models. Evidence for sensitive periods did not emerge strongly in these data. These findings underscore the need to measure the characteristics of adversity, which can aid in understanding disease mechanisms and determining how best to reduce the consequences of exposure to adversity.

Introduction

One of the most consistent findings in psychiatric epidemiology is that childhood adversity, including maltreatment and stressful life events, is one of the most potent determinants of mental health problems throughout the lifespan (Shonkoff and Garner, 2012). Overall, childhood adversities appear to at least double the risk of youth- and adult-onset mental disorders (McLaughlin et al., 2010, McLaughlin et al., 2012, Gilman et al., 2015). Yet, relatively little is known about how the characteristics of adversity influence subsequent mental health outcomes. For instance, does the developmental timing of exposure to adversity matter most in shaping future risk for psychopathology symptoms? Or is the duration of exposure more important? A greater understanding of how the features of adversity are associated with mental health outcomes could shed new light on the mechanisms underlying risk for psychopathology, by suggesting developmental processes that are disrupted through exposure. It could also help in determining the optimal times to intervene, as childhood spans multiple developmental periods when different types of interventions (e.g., home- vs. school based programs) could be deployed to minimize the effects of adversity based on the age of the child or the nature of the exposure.

Here, we compared three theoretical models derived from life course theory, each of which describes the association between an exposure and a health outcome (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh, 2002, Kuh and Ben-Shlomo, 2004), to determine the model(s) that best explained the relationship between exposure to childhood adversity on emotional and behavioral problems at age 8. The first life course model tested was an accumulation of risk model, which posits that every additional year of exposure is associated with an increased risk of poor health in a dose-response manner, irrespective of timing (Evans et al., 2013, Rutter et al., 1979). The second model was a sensitive period model, which presumes the developmental timing of exposure is most important. In this model, timing matters because the exposure occurrence coincides with the time period of greatest maturation or plasticity in the brain, for example (Bailey et al., 2001, Knudsen, 2004), making the exposure at one point in time more potent than the same exposure occurring earlier or later (Dunn et al., 2013). The third model was a recency model, which suggests that mental health outcomes are most strongly linked to more proximal, rather than distal events, as the effects of adversity can be time-limited (Shanahan et al., 2011). To our knowledge, no studies have simultaneously conducted formal comparisons of these three theoretical models across the main types of adversity related to psychopathology.

We aimed to address this gap by using an innovative life course modeling approach (Mishra et al., 2009) to simultaneously compare these theoretical models with four of the main types of early life adversity linked to psychopathology: caregiver physical or emotional abuse, sexual or physical abuse, financial stress and parent legal problems. These adversities were measured repeatedly between birth and age 8. Our goal was to determine which theoretical model (or set of models) were best supported by the data, estimate the magnitude of association between each model and child psychopathology symptoms, and evaluate whether the model chosen varied by the type of exposure. We performed these analyses separately among boys and girls, as prior studies have shown sex differences in lifetime exposure to adversity (Koenen et al., 2010) and risk for psychopathology (Dunn et al., 2012). Although these life course models are often described in relation to adult outcomes, and the period of childhood is often considered a sensitive period in and of itself, we focused on child psychopathology symptoms in order to examine the short-term consequences of adversity and determine the possibility of being able to differentiate between these life course models for early-onset psychopathology symptoms.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Data came from a prospective, longitudinal birth-cohort of children (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; ALSPAC, Boyd et al. 2012). ALSPAC sampled children born to mothers living in the county of Avon, England (120 miles west of London) with estimated delivery dates between April 1991 and December 1992. Approximately 85 percent of eligible pregnant women agreed to participate (n=14,541), and 99% of eligible live births (n=14,775) who were alive at 12 months of age (n=14,701 children) were enrolled. Response rates have been good (75% completed at least one follow-up). More details are available on the ALSPAC website including a fully searchable data dictionary: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/access/. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

Exposure to Abuse and Stress

We examined four types of adversity measured using parent-mailed questionnaires. Each adversity was measured on at least five occasions before age 8 (see Table 1), with each measurement occasion analyzed separately due to different assessment time periods. The adversity types selected are commonly used to define “early life adversity” (Felitti et al., 1998, Slopen et al., 2012, Slopen et al., 2014). The abuse-related variables were chosen because they aligned with previous work demonstrating the strong association between physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and subsequent mental disorders (Norman et al., 2012, Maniglio, 2009). Similarly, the stress-related variables were chosen based on previous work linking parental incarceration (Murray and Murray, 2010, Turney, 2014) and financial stress (Evans, 2004) to risk for psychopathology.

Table 1.

Description of the lifecourse theoretical models tested in the current analysis, using exposure to abuse as an example

| Life course model tested | Definition | Number of Variables |

Specific variables entered into the LARS model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accumulation of risk (by duration) | Sum of the total number of time periods of exposure to a specific adversity. To test whether the total number of time periods of exposure to a given adversity explains the most variance in psychopathology outcomes. | 1 | abuse_accumulation=count of the number of time periods exposed to abuse (range 0–6) |

| Sensitive period | A single developmental time period at which there can be exposure to adversity. To test if presence vs. absence of a given adversity at a specific time period explains the most variance in psychopathology outcomes. | 6 | abuse_period1= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 1 (18 months) ; abuse_period2= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 2 (30 months); abuse_period3= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 3 (42 months); abuse_period4= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 4 (57 months); abuse_period5= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 5 (69 months); abuse_period6= exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) at time period 6 (81 months) |

| Recency | Sum of the total number of time periods of exposure to a given adversity, with each time period weighted by the age in years of the child during the exposure. To test if temporal proximity to adversity events explains the most variance in psychopathology outcomes. | 1 | abuse_recency= abuse_period1 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0)*(18/12) + abuse_period2 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) *(30/12) + abuse_period3 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) *(42/12) + abuse_period4 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) *(57/12) + abuse_period5 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) *(69/12) + abuse_period6 exposed (1) vs. unexposed (0) *(81/12) |

For each type of adversity, we generated three sets of encoded variables: (a) a single variable denoting the total number of time periods of exposure to a given adversity, to test the accumulation hypothesis (coded as 0–6); (b) a set of variables indicating presence vs. absence of the adversity at a specific developmental stage, to test the sensitive period hypothesis; and (c) a single variable denoting the total number of time periods of exposure, with each exposure linearly weighted by age (in months) of the child during the measurement time period, to test the recency hypothesis; this variable assumed a linear increase in the effect of exposure over time and weighted more recent exposures more heavily than distally-occurring ones, allowing us to determine whether more recent exposures were more impactful (Smith et al., 2016). This weighted recency variable is distinguished from the last sensitive period model, which captures only the most recent exposure.

Abuse

Caregiver physical or emotional abuse

Children were coded as having been exposed to physical or emotional abuse if the mother, partner, or both responded affirmatively to any of the following items: (1) Your partner was physically cruel to your children; (2) You were physically cruel to your children; (3) Your partner was emotionally cruel to your children; (4) You were emotionally cruel to your children.

Sexual or physical abuse

Exposure to sexual or physical abuse was determined through an item asking the mother to indicate whether or not the child had been exposed to either sexual or physical abuse from anyone.

Stress

Financial stress

Mothers indicated using a Likert-type scale (1=not difficult; 2=slightly difficult; 3=fairly difficult; 4=very difficult) the extent to which the family had difficulty affording the following: (a) items for the child; (b) rent or mortgage; (c) heating; (d) clothing; (e) food. Children were coded as exposed if their mothers reported at least slight difficulty for three or more items; this cut-point roughly corresponded to the top quartile.

Parent legal problems

Mothers indicated whether or not the child’s parents had been in trouble with the law in the past year. Children were coded as exposed if either or both parents had legal problems.

For each type of adversity, we generated three sets of encoded variables, as summarized in Table 1. These encoded variables were all entered into a single multiple regression model for a given type of adversity, allowing for multiple life course associations to be present simultaneously.

As no clear sensitive periods link exposure to adversity and risk for psychopathology have been identified, we made full use of available ALSPAC data and coded each sensitive period model based on the time periods when adversity was measured in the ALSPAC dataset, enabling us to use a more fine-grained set of measures (i.e., specific ages of exposure) to detect possible sensitive periods. However, to facilitate interpretation of our findings and compare our results to prior studies, which have used similar but slightly broader age categories to define sensitive periods (Andersen et al., 2008, Kaplow and Widom, 2007, Dunn et al., 2016, Slopen et al., 2014), we present our results (examining each specific age stage of exposure) according to three developmental periods – very early childhood, ages 0–3; early childhood, ages 4–5; middle-childhood, ages 6–7.

Child Psychopathology

Child emotional and behavioral problems were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997, Goodman, 2001), which mothers completed by mail when the child was 8 years old. The SDQ is one of the most commonly used dimensional ratings of child psychopathology in epidemiology studies and has excellent psychometric properties (Ezpeleta et al., 2013, Muris et al., 2003). The SDQ contains 25 items, rated on a three-point scale (0=not true, 1=somewhat true, or 2=certainly true), capturing the child’s behavior and feelings within the past six months. We calculated a total SDQ score by summing across items on the first four subscales (conduct problems; emotional symptoms; hyperactivity; peer problems; range 0–40), with higher scores indicating more emotional and behavioral difficulties (α=0.82). This total score has been shown in studies from across the globe to correlate highly with questionnaire and interview measures of psychopathology, including the Child Behavior Checklist as well as clinician-rated diagnoses of child mental disorder (Goodman et al., 2010, Goodman and Goodman, 2011).

Covariates

We controlled for the following covariates, measured at child birth: child race/ethnicity; pregnancy size; number of previous pregnancies; maternal age; maternal marital status; homeownership; highest level of maternal education; and parent social class (see Supplemental Materials for coding). We also controlled for levels of maternal psychopathology symptoms measured during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., 1987) to reduce potential impacts of both confounding and common rater bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), as mothers reported about their child’s emotional and behavioral problems, mothers were the primary reporters of their child’s exposure to adversity, and maternal mood or other factors may influence reports of adversity exposure (Holt et al., 2008) and psychopathology (Chilcoat and Breslau, 1997, Ringoot et al., 2015). The covariates were included because they were found in our study to be potential confounders or were routinely included in birth cohort studies of child health outcomes (Hibbeln et al., 2007, Suren et al., 2014). Both sets of results with and without adjustment for maternal psychopathology symptoms are presented to facilitate future replication efforts.

Analyses

After conducting univariate and bivariate analyses to examine the distribution of covariates and exposure to adversity in the total analytic sample, we compared the theoretical models using a two-stage structured life course modeling approach (SLCMA) originally developed by Mishra (Mishra et al., 2009) for analyzing repeated, binary exposure data across the life course. Relative to a more traditional regression model, the main advantage of the SLCMA is that it provides a structured and unbiased way to compare multiple competing theoretical models simultaneously and identify the most parsimonious explanation for the observed outcome variation.

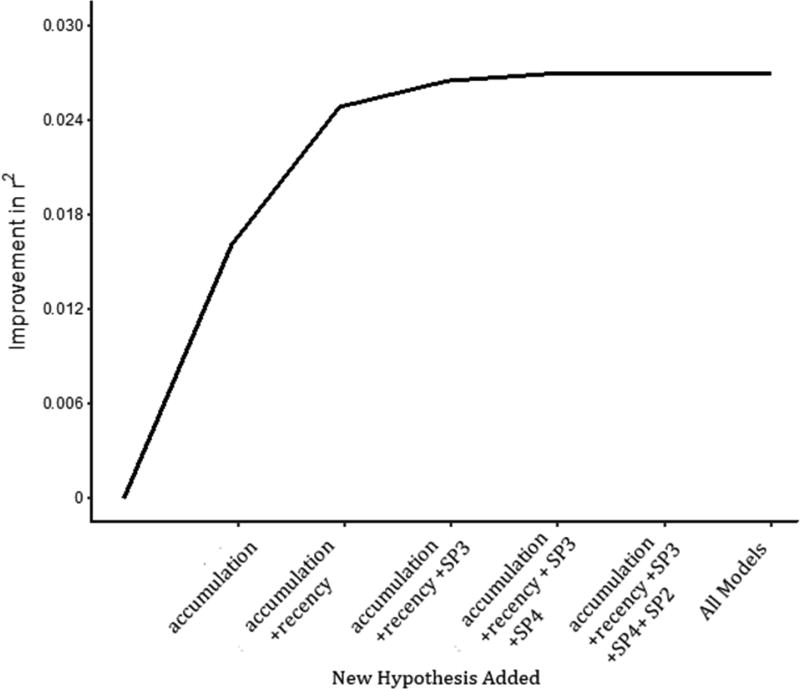

In the first stage, we followed the approach of Smith (Smith et al., 2015) and entered the set of variables described previously into a Least Angle Regression (LARS) procedure (Efron et al., 2004) in order to identify, separately for each type of adversity, the single theoretical model (or potentially more than one models working in combination) that explained the most variability in child emotional and behavioral problems. Thus, four separate LARS models were conducted, corresponding to each type of adversity, separately for boys and girls. We used a covariance test (Lockhart et al., 2014) and examined elbow plots (Figure 1) to determine whether the selected models were supported by the ALSPAC data. Compared to other variable selection procedures, including stepwise regression, the SLCMA has been shown to not over-inflate effect size estimates (Efron et al., 2004) or bias hypothesis tests (Lockhart et al., 2014). Compared to other methods for the structured approach, LARS has been shown to have greater statistical power and not bias subsequent stages of analysis (Smith et al., 2015). Notably, the covariance test p-values derived from the LARS also account for the other variables being (sequentially) tested in the procedure, making the type I error rate is controlled for each type of adversity.

Figure 1.

Elbow plot illustrating the LARS variable selection procedure testing life course models

LARS begins by first identifying the single variable with the strongest association to the outcome; it then identifies the combination of two variables with the strongest association, followed by three variables, and so on, until all variables are included. LARS therefore achieves parsimony by identifying the smallest combination of encoded variables that explain the most amount of outcome variation. In addition to a covariance test, which is calculated at each stage of the LARS procedure and tests the null hypothesis that adding the next encoded variable does not improve r2, results can also be summarized in an “elbow plot,” showing the increase in overall model r2 as additional predictors were added to the model. The point where this plot levels off indicates the point of diminishing marginal improvement to the model goodness-of-fit from adding additional predictors, suggesting that the predictors included in the model at this point represent an optimal balance of parsimony and thoroughness. In this example, both accumulation and recency were selected in the best fitting models. SP =Sensitive Period.

All analyses were stratified by sex. To adjust for potential confounding, we regressed each encoded variable on the covariates and implemented LARS on the regression residuals (Smith et al., 2016).

In the second stage, the theoretical models determined by a covariance test p-value threshold of 0.05 in the first stage (which appeared before the elbow; see Figure 1) were carried forward to a single multiple regression framework, where measures of effect were estimated for all selected hypotheses. The goal of this second stage was to determine the contribution of a selected theoretical model after adjustment for covariates as well as other selected theoretical models, in instances where more than one theoretical model was chosen in the first stage. To reduce potential bias and minimize loss of power due to attrition, we performed multiple imputation in both stages (see Supplemental Materials).

Results

Sample Characteristics and Distribution of Exposure to Adversity

The imputed analytic sample (n=7,476) was gender-balanced (49.2% girls) and comprised of predominately White (94.6%) children from families whose parents were married and owned their home (Supplemental Table 1).

Approximately half of the children in this analytic sample (49%; n=3694) experienced at least one adversity. As shown in Table 2, the most commonly experienced adversity, for both boys and girls, was financial stress (32% girls; 30% boys). Parent legal problems was the least reported (6% in girls and boys).

Table 2.

Exposure to childhood adversity overall and by age at exposure

| Abuse | Stress | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Caregiver physical or emotional abuse |

Sexual or physical abuse (by anyone) |

Financial stress | Parent legal problems | |||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Unexposed | 2159 | 83 | 2273 | 83 | 2335 | 90 | 2352 | 86 | 1982 | 68 | 2098 | 70 | 2402 | 94 | 2531 | 94 |

| Exposed | 446 | 17 | 471 | 17 | 270 | 10 | 394 | 14 | 936 | 32 | 890 | 30 | 160 | 6 | 155 | 6 |

| Timing of Exposure | ||||||||||||||||

| Very Early Childhood | ||||||||||||||||

| Age 8 mo. | 92 | 3.5 | 103 | 3.8 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 351 | 12 | 334 | 11 | 25 | 1 | 32 | 1.2 |

| Age 1.5/1.75 | 103 | 4 | 100 | 3.7 | 49 | 1.9 | 70 | 2.6 | 350 | 12 | 346 | 12 | 37 | 1.5 | 29 | 1 |

| Age 2.5/ 2.75 | 138 | 5.3 | 168 | 6.1 | 75 | 2.9 | 123 | 4.5 | 344 | 12 | 328 | 11 | 44 | 1.7 | 47 | 1.8 |

| Early Childhood | ||||||||||||||||

| Age 3.5 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 59 | 2.3 | 86 | 3.1 | 375 | 13 | 338 | 11 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Age 4/4.75 | 147 | 5.6 | 125 | 4.6 | 56 | 2.2 | 117 | 4.3 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 44 | 1.7 | 37 | 1.4 |

| Age 5/5.75 | 166 | 6.4 | 197 | 7.2 | 60 | 2.3 | 101 | 3.7 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 33 | 1.2 | 36 | 1.3 |

| Middle Childhood | ||||||||||||||||

| Age 6/6.75 | 168 | 6.5 | 139 | 5.1 | 61 | 2.3 | 94 | 3.4 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 34 | 1.3 | 36 | 1.3 |

| Age 7 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 304 | 10 | 297 | 9.6 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

Percentages for each age represent proportions of those exposed out of the total population.

--- indicates that the variable was not assessed at the corresponding time point

Age at exposure to adversity somewhat varied by type. For instance, caregiver physical or emotional abuse was more common in middle childhood than infancy (Table 2). However, the remaining adversities were primarily reported with the same frequency across time.

Within each adversity type, exposure was correlated over time (Table 3; average correlations: caregiver abuse r=0.61; abuse by anyone r=0.44; legal problems r=0.52; financial stress r=0.54). In general, neighboring time points were more highly correlated than distant time points. However, across adversity types, the exposures were only modestly correlated (Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Figure 1; average correlation across adversity types r=0.24).

Table 3.

Tetrachoric correlations between childhood adversities

| Caregiver physical or emotional abuse (N=5349) | Sexual or physical abuse (by anyone) (N=5351) | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Age | 8 mo | 1.75 | 2.75 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Age | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.75 | 5.75 | 6.75 | ||

| 8 mo | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.5 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 1.75 | 0.71 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 2.75 | 0.61 | 0.7 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | 3.5 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.69 | 1 | --- | --- | 4.75 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.5 | 1 | --- | --- | ||

| 5 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 1 | --- | 5.75 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 1 | --- | ||

| 6 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 1 | 6.75 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 1 | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Financial stress (N=5906) | Parent legal problems (N=5248) | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Age | 8 mo | 1.75 | 2.75 | 5 | 7 | Age | 8 mo | 1.75 | 2.75 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 8 mo | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 8 mo | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||

| 1.75 | 0.69 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | 1.75 | 0.64 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||

| 2.75 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 1 | --- | --- | 2.75 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 1 | --- | --- | --- | |||

| 5 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 1 | --- | 4 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 1 | --- | --- | |||

| 7 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1 | 5 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 1 | --- | |||

| 6 | 0.4 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.5 | 0.58 | 1 | |||||||||

Both exposure to any adversity and child emotional and behavioral problems were patterned by socio-demographic factors, including sex, and socioeconomic status (Supplemental Table 1).

Model Selection

Table 4 shows the models selected by the LARS procedure for each adversity type, in boys and girls. Overall, recency was the theoretical model best supported by the data for the abuse-related adversities.

Table 4.

Results of LASSO models on multiply imputed data, stratified by sex

| Female (N=3676) | Male (N=3800) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Model(s) selected | r2 explained | Model(s) selected | r2 explained | |

|

|

||||

| Abuse | ||||

|

|

||||

| Caregiver physical or emotional abuse | Recency | 1.55% | Accumulation | 1.71% |

| Sexual or physical abuse | Recency and Sensitive Period in Middle Childhood (age 6.75 years) | 2.35% | Recency | 1.68% |

| Stress | ||||

| Financial Stress | Accumulation and Sensitive Period in Very Early Childhood (age 8 months) | 3.08% | Accumulation | 1.39% |

| Parent legal problems | Accumulation | 0.51% | Sensitive Period in Very Early Childhood (age 8 months) | 0.29% |

The table indicates the set of theoretical models chosen by the LASSO, after adjusting for covariates.

In girls, recency of caregiver physical or emotional abuse explained 1.55% of the variation in child emotional and behavior problems. The combination of recency and exposure to physical or sexual abuse during middle childhood (at 6.75 years of age), the last time point of assessment for this exposure, explained 2.35% of the variation in child emotional and behavior problems. Further, both accumulation and exposure to financial stress during infancy (at 8 months of age) were selected. Accumulation of parent legal problems explained 0.51% of the variation in emotional and behavioral problems.

In boys, accumulation was the best theoretical model chosen for caregiver physical or emotion abuse, explaining 1.71% of the variation in child emotional behavior problems. Recency of sexual or physical abuse explained 1.68% of the variation in boys. Moreover, accumulation was selected as the single best fitting model for financial stress (r2=1.39%), whereas for parent legal problems, exposure during infancy (at 8 months of age) was most important (r2=0.29%).

Model selection results were similar after adjusting for maternal depression (Supplemental Table 4), though two differences are noted. In girls, exposure to financial stress during sensitive period 1 (at 8 months of age) was not significantly associated with emotional and behavior problems; accumulation was the theoretical model best supported by the data (r2=0.76%). In boys, recency of caregiver physical or emotional abuse replaced accumulation as the best supported model (r2=0.89%).

Out of all combinations of theoretical models considered for all adversities, financial stress was the type of adversity that explained the largest amount of variation in psychopathology symptoms among girls (r2=3.08%). Among boys, sexual or physical abuse was the most strongly associated type (r2=1.68%).

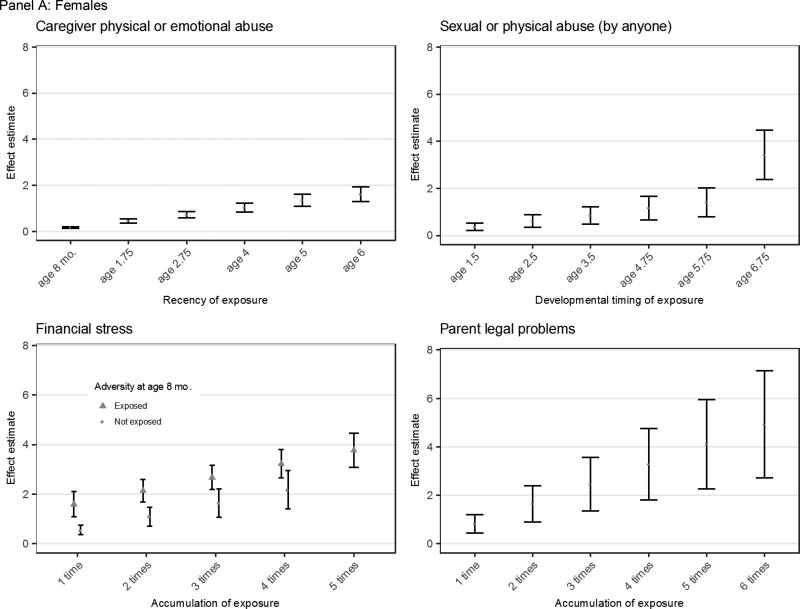

Effect Estimation

After identifying the theoretical models shown in the first stage to explain the most outcome variation, we then entered these models into a multiple linear regression. As shown in Figure 2, Panel A, which presents these results for girls, we found that girls exposed to caregiver physical or emotional abuse during more recent developmental periods had the largest increase in emotional and behavior problems as compared to those exposed during earlier time periods (an increase of 0.27 for every additional year of exposure, 95% CI=0.22, 0.32; standardized mean difference for exposure at age 6 (SMD6y=0.34). The association with exposure to sexual or physical abuse increased linearly with proximity of exposure, such that girls exposed at more recent developmental periods had the most emotional and behavioral problems (β=0.24; 95% CI=0.14, 0.35; SMD6.75y=0.35). Further, the association with exposure to sexual or physical abuse also increased with proximity of exposure, but in a non-linear fashion such that exposure at age 6.75 was a particularly sensitive period, conferring an additional increase in symptoms (β=1.78; 95% CI=0.21, 3.35; SMD6.75y=0.38). For financial stress, where two theoretical models were also chosen, each time period of exposure was linearly associated with an increase of 0.54 (95% CI= 0.35, 0.73; SMD5=0.58), though girls exposed to financial stress at age 8 months had an additional increase of 1.05 (95% CI=0.41, 1.68; SMD8mo=0.22) in the measure of emotional and behavior problems. More time periods of exposure to parent legal problems were also linearly associated with increasing emotional and behavior problems (an increase of 0.82 per event, 95% CI=0.45, 1.19; SMD6=1.04).

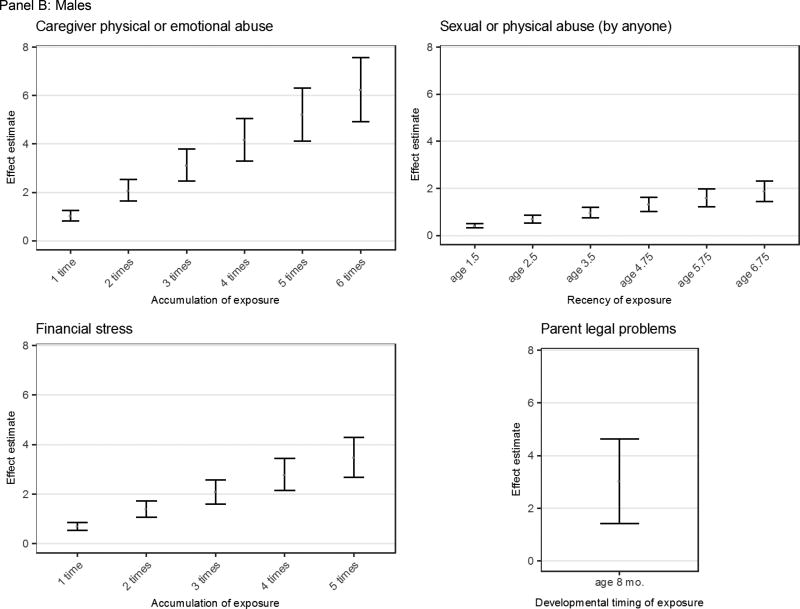

Figure 2.

Effect estimates for exposure to adversity, stratified by sex

The effect estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals demonstrate the increase in SDQ scores for exposure to adversity during a certain time point or number of exposures. For accumulation, an increase in the number of time points exposed corresponds to a greater increase in SDQ score. For recency, exposure to adversity during later time points corresponds to a greater increase in SDQ score.

As shown in Figure 2, Panel B, boys exposed to sexual or physical abuse more recently had higher emotional and behavioral problems (an increase of 0.28 per additional year of exposure; 95% CI=0.21, 0.34; SMD6.75y=0.36). More time periods of exposure to either caregiver physical or emotional abuse or financial stress were linearly associated with increasing emotional and behavior problems (increases of 1.04 per event, 95% CI=0.82, 1.26; SMD6=1.18, and 0.70 per event, 95% CI=0.53, 0.86; SMD5=0.66 respectively). Exposure to parent legal problems at 8 months of age was associated with increased child psychopathology (β=3.03; 95% CI=1.43, 4.64; SMD8mo=0.57).

Discussion

The primary finding of this study is that child psychopathology symptoms were largely explained by the accumulation and recency of exposure to adversity, rather than sensitive periods. Specifically, for either type of abuse, we found that more recently occurring exposures were generally more harmful, as the LARS procedure most frequently selected the recency model for this type of adversity. This finding is consistent with at least one prior study testing the recency hypothesis (Shanahan et al., 2011) and other work showing that the depressogenic effects of adversity are elevated in the same month or month after the event (Kendler et al., 1999) or the same year of exposure (Dunn et al., 2012). Accumulation was the second theoretical model selected most frequently. Dozens of studies have shown that chronic or cumulative exposure to adversity is harmful for mental health and other outcomes (Evans et al., 2013).

However, only two clear sensitive periods were identified. The first was for financial stress in girls, where we found that both accumulation and exposure during very early childhood were most strongly associated with child emotional and behavior problems. That is, while each additional time-period of exposure was linearly associated with an increase in psychopathology symptoms, girls first exposed to financial stress at age 8 months had even worse emotional and behavioral problems with more accumulated exposure. The second sensitive period observed was for parent legal problems, where we found that exposure at age 8 months had the strongest association with psychopathology symptoms. Therefore, our results on this occasion provide limited additional insight compared with studies that only examined whether or not a child was exposed.

Why did so few sensitive periods emerge? Our inability to identify sensitive periods was surprising, given that numerous animal studies have found time-dependent effects of adversity on a range of outcomes, including not only anxious/depressive symptoms (Raineki et al., 2012), but also social, emotional, and behavioral processes (e.g., fear conditioning, stress reactivity, aggressive behavior (Veenema, 2009, Holmes et al., 2005, Sanchez et al., 2001), and brain structure and function (Makinodan et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2012). However, in the human literature, there is mixed support for the existence of sensitive periods shaping risk for psychopathology. Research on the importance of the developmental timing of child maltreatment on depression risk provides a good illustration of such inconsistencies. Several prospective studies have found higher levels of internalizing symptoms in early childhood (Keiley et al., 2001) and depressive symptoms in early (Thornberry et al., 2010) and early to mid-adulthood (Kaplow and Widom, 2007) among individuals exposed to child maltreatment before age 5 compared to those who were either never exposed or exposed during later stages. However, several prospective studies have found no effect of maltreatment timing (English et al., 2005, Jaffee and Maikovich-Fong, 2011, Manly et al., 2001) or that maltreatment exposure during adolescence is more harmful than exposure during earlier developmental stages (Harpur et al., 2015, Thornberry et al., 2001). Conflicting findings could reflect differences in the length of time between the onset of adversity and measurement of the outcome, showcasing more “recency” rather than sensitive period effects. Our future research will perform similar analyses in relation to outcomes measured during adolescence and adulthood, which would help evaluate the longer-term effects of adversity on both the onset and course of psychopathology symptoms and help determine whether the lack of distinct sensitive periods within childhood is common to other outcomes. Heterogeneity in the literature could be explained by the fact that there are unlikely sensitive periods for psychopathology per se. Instead, adversity likely disrupts multiple intermediate processes linked to psychopathology, including attention and emotion recognition; each of these domains could have their own sensitive period.

As expected, sex differences were observed. For example, there were instances when more than one theoretical model was operating simultaneously to produce mental health outcomes in one sex, but a single theoretical model was operating for another. Importantly, these differences did not appear driven by sex differences in the prevalence of exposure, as boys and girls were exposed to each of these adversities at the same frequency. Future studies are needed to understand the factors giving rise to these sex differences and replicate findings regarding the importance of developmental timing, as few studies in this area have been conducted (Najman et al., 2010b, Najman et al., 2010a).

Although the variance explained by each of these best fit models may at first appear small, it bears noting that these life course models are examining a single adversity type in a large population-based sample, as opposed to a cumulative adversity score in a clinical sample. Moreover, unlike models examining the variance explained by a given exposure, the examined life course models are examining effect sizes for the temporal patterns of certain exposures. Thus, the size of the reported R2 values is on par with what we might expect given the temporal specificity of the models and the population-based nature of the sample.

This study has several strengths. We conducted these analyses in a large, longitudinal, and population-based sample of children, which minimized the likelihood of retrospective recall bias that is common among studies of childhood adversity and allowed us to evaluate the short-term consequences of adversity on psychopathology symptoms. We also applied a novel analytic approach that enabled us to simultaneously compare these theoretical models and evaluate the impact of each theoretical model to each adversity type. Comparisons of these models by type of adversity may contribute to insights about the mechanisms underlying psychopathology risk. Information about the types and features of adversity that are most strongly associated with childhood psychopathology may also help identify highest priority points for intervention.

We also considered exposures individually, rather than simultaneously, which was arguably both a strength and limitation. On the one hand, focusing on one type of childhood adversity without accounting for the impact of highly correlated exposures can artificially inflate effect estimates for the single adversity type (Green et al., 2010, Dong et al., 2005). However, in our sample, the adversities examined were only modestly correlated with each other. Of note, the clustering of different types of adversity experiences with typically high co-occurrence, such as physical and emotional abuse and sexual and emotional abuse (which was done through the combined format in the questionnaire), may help account for our lower inter-correlations between adversity experiences in this sample.

On the other hand, attention to specific adversity types – and in particular the time-course of exposure to these adversity types – proved meaningful for understanding adversity-specific associations to risk for psychopathology. The finding that different life course models differentially explained the association between childhood adversity and psychopathology symptoms suggests that grouping adversity experiences could have obscured these distinctions. An important next step would be to consider ways to examine multiple adversities simultaneously, so that meaningful information could be gleaned without simply summing across the number of adversities experienced (McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016).

Several limitations are noted. The use of single items to capture adversity could affect the precision of these estimates. However, the prevalence of these adversities, including those capturing experiences of abuse, were comparable to estimates derived from nationally-representative samples (McLaughlin et al., 2012, Gilbert et al., 2009). As with any longitudinal study, there was attrition over time, which we attempted to address using multiple imputation. We were also unable to examine the impact of experiencing multiple adversities simultaneously because these adversities were measured at different time points. Furthermore, the socio-demographic covariates were only measured at birth, which may be problematic as some of these variables could be time-varying, including indicators of socioeconomic status. Finally, although we controlled for several potential confounding factors, including maternal psychopathology, it is possible that residual confounding may remain, including through unmeasured genetic factors that shape both exposure and outcome (i.e., gene-environment correlation). As more genetic variants associated with neuropsychiatric phenotypes emerge from genome-wide association studies, future studies will be better positioned to ensure that study results are not explained by genetic factors.

In summary, our results suggest that no single theoretical model best captures the relationship between adversity and mental health problems, but rather that depending on sex and the type of exposure, adversities can operate through different pathways. These findings underscore the importance of measuring the characteristics of adversity, which can help further elucidate the most important environmental risk factors shaping child mental health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Stephanie Gomez, and Emily Moya for their assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Financial Support: The UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors, who will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. This research was specifically funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (E.C.D., Award Number K01MH102403 and R01MH113930) and a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Ethical Standards: All ethical guidelines were followed per research involving use of human subjects.

References

- Andersen SL, Tomada A, Vincow ES, Valente E, Polcari A, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences. 2008 doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.3.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB, Bruer JT, Symons FJ, Lichtman J, editors. Critical thinking about critical periods. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chroic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges, and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Davey Smith G. Cohort profile: The 'Children of the 90's'- the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Does psychiatric history bias mothers' reports? An application of a new analytic approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:971–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Williamson DF, Dube SR, Brown DW, Giles WH. Childhood residential mobility and multiple health risks during adolescence and adulthood: the hidden role of adverse childhood experiences. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:1104–10. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Gilman SE, Willett JB, Slopen N, Molnar BE. The impact of exposure to interpersonal violence on gender differences in adolescent-onset major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:392–399. doi: 10.1002/da.21916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Mclaughlin KA, Slopen N, Rosand J, Smoller JW. Developmental timing of child maltreatment and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in young adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30:955–64. doi: 10.1002/da.22102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Nishimi K, Powers A, Bradley B. Is developmental timing of trauma exposure associated with depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adulthood? Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Hastie T, Johnstone I, Tibshirani R. Least angle regression. The Annals of Statistics. 2004;32:407–499. [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:575–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist. 2004;59:77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:342–396. doi: 10.1037/a0031808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, De La Osa N, Penelo E, DomÈnech JM. Psychometric properties of the strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire3–4 in 3-year-old preschoolers. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013;54:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards VJ, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationships of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Spatz Widom C, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Child maltreatment 1: Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Ni MY, Dunn EC, Breslau J, Mclaughlin KA, Smoller JW, Perlis RH. Contributions of the social environment to first-onset and recurrent mania. Molecular Psychiatry. 2015;20:329–36. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Goodman R. Population mean scores predict child mental disorder rates: validating SDQ prevalence estimators in Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:100–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB. When to use broader internalizing and externalizing subscales instead of the hypothesized five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ); Data from British parents, teachers, and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:1179–1191. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The strenghts and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strenghts and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, Mclaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslvasky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication I: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpur LJ, Polek E, Van Harmelen AL. The role of timing of maltreatment and child intelligence in pathways to low symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Steer C, Emmett P, Rogers I, Williams C, Golding J. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): An observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2007;369:578–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Le Guisquet AM, Vogel E, Millstein RA, Leman S, Belzung C. Early life genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors shaping emotionality in rodents. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Maikovich-Fong AK. Effects of chronic maltreatment and maltreatment timing on children's behavior and cognitive abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:184–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Widom CS. Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:176–87. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen E. Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:1412–1425. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Roberts A, Stone D, Dunn EC. The epidemiology of early childhood trauma. In: Lanius R, Vermetten E, editors. The hidden epidemic: The impact of early life trauma on health and disease. New York, NY: Oxford University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Dietz K, Deloyht JM, Pedre X, Kelkar D, Kaur J, Vialou V, Lobo MK, Dietz DM, Nestler EJ, Dupree J, Casaccia P. Impaired adult myelination in the prefrontal cortex of socially isolated mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:1621–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart R, Taylor J, Tibshirani RJ, Tibshirani R. A significance test for the LASSO. Annals of Statistics. 2014;42:413–468. doi: 10.1214/13-AOS1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. A critical period for social experience-dependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science. 2012;337:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1220845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: a systematic review of reviews. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:647–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication II: Associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:124–132. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2012;69:1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin KA, Sheridan MA. Beyond Cumulative Risk: A Dimensional Approach to Childhood Adversity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2016;25:239–245. doi: 10.1177/0963721416655883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra G, Nitsch D, Black S, De Stavola B, Kuh D, Hardy R. A structured approach to modelling the effects of binary exposure variables over the life course. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38:528–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Van den Berg F. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)--further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;12:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Clavarino A, Mcgee TR, Bor W, Williams GM, Hayatbakhsh MR. Timing and chronicity of family poverty and development of unhealthy behaviors in children: a longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010a;46:538–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Clavarino A, Bor W, O'callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: a longitudinal study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010b;100:1719–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C, Cortes MR, Belnoue L, Sullivan RM. Effects of early-life abuse differ across development: infant social behavior deficits are followed by adolescent depressive-like behaviors mediated by the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:7758–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5843-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringoot AP, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VW, So P, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, Jansen PW. Parental depression and child well-being: young children's self-reports helped addressing biases in parent reports. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68:928–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Maughan B, Mortimore P, Outston J. Fifteen thousand hours: Secondary schools and their effects on children. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: Evidence from rodent and primate models. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:419–449. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, Angold A. Child-, adolescent- and young adult-onset depressions: differential risk factors in development? Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:2265–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Cumulative adversity in childhood and emergent risk factors for long-term health. Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;164:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, Mclaughlin KA, Koenen KC. Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Hardy R, Heron J, Joinson CJ, Lawlor DA, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K. A structured approach to hypotheses involving continuous exposures over the life course. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Heron J, Mishra G, Gilthorpe MS, Ben-Shlomo Y, Tilling K. Model Selection of the Effect of Binary Exposures over the Life Course. Epidemiology. 2015;26:719–26. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suren P, Gunnes N, Roth C, Bresnahan M, Hornig M, Hirtz D, Lie KK, Lipkin WI, Magnus P, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Schjolberg S, Susser E, Oyen AS, Smith GD, Stoltenberg C. Parental obesity and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1128–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The causal impact of childhood-limited maltreatment and adolescent maltreatment on early adult adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:957–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH. Early life stress, the development of agression and neuroendocrine and neurobiological correlates: What can we learn from animal models. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2009;30:497–518. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.