A new binding pocket of the endogenous ligand has been discovered by MD simulations.

A new binding pocket of the endogenous ligand has been discovered by MD simulations.

Abstract

Identifying a target ligand binding site is an important step for structure-based rational drug design as shown here for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are among the most popular drug targets. We applied long-time scale molecular dynamics simulations, coupled with mutagenesis studies, to two prototypical GPCRs, the M3 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Our results indicate that unlike synthetic antagonists, which bind to the classic orthosteric site, the endogenous agonist acetylcholine is able to diffuse into a much deeper binding pocket. We also discovered that the most recently resolved crystal structure of the LTB4 receptor comprised a bound inverse agonist, which extended its benzamidine moiety to the same binding pocket discovered in this work. Analysis on all resolved GPCR crystal structures indicated that this new pocket could exist in most receptors. Our findings provide new opportunities for GPCR drug discovery.

Introduction

Many essential cellular processes, including cell regulation, signal transduction, and the immune response, are mediated by specific protein–ligand interactions. The identification and characterization of specific protein binding sites for particular ligands are crucial for the understanding of the functions of both endogenous ligands and synthetic drug molecules.1–3 Thus, the detection and characterization of ligand binding sites are important steps towards protein function identification and drug discovery.4–7 A newly revealed ligand binding site will provide a new opportunity for a drug target, to design new classes of compounds based on new chemical environments.8 Besides traditional biochemical methods such as systematic mutagenesis experiments, structural biology or NMR,9 computational methods offer alternative powerful and efficient approaches for ligand binding site detection.7,10

In this work, we applied molecular dynamics simulations and computer modeling, combined with functional mutagenesis experiments, to explore new ligand binding sites of GPCRs. GPCRs typically detect extracellular signals (photons, odorants, hormones, and neurotransmitters)11,12 on the cell surface and undergo multiple conformational changes that enable the binding and activation of intracellular proteins (e.g. G-proteins, arrestins and kinases).13–16 More than a third of modern therapeutic compounds are estimated to target GPCRs.7 Thus, understanding the ligand binding process and detecting a new ligand binding site for GPCRs in molecular details are of great importance in revealing GPCR-mediated signaling and improving GPCR-targeted drug design. Recent crystal structures of GPCRs show that different small molecules can bind to different regions of receptors including (1) the traditional orthosteric ligand binding site in the vicinity of the highly conserved (W6.48),17 (2) the allosteric ligand binding site next to extracellular loop 2 (ECL2),18,19 (3) allosteric ligand binding sites between transmembrane (TM) helices TM2 and TM3,18,19 (4) allosteric ligand binding sites between TM3 and TM4,20 (5) the intracellular G protein binding region21 and (6) the outer surface of the receptor in the middle of the TM area22 (Fig. S1†).

Computational methods have become important tools for understanding the structural and dynamical function of GPCRs.7,23 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and computational modeling can be used to address specific questions about the dynamic properties of the modelled system, which are difficult to illuminate in experiments. For example, with MD simulations, it is possible to sample the process of ligand binding to a specific GPCR.24–26 Many atomic details, including molecular switches, binding site expansions or domain movements, can be efficiently revealed through MD simulations.27–30

Here we explore a new ligand binding site for two GPCRs, muscarinic M3 and M4 receptors, which specifically activate Gαq and Gαi proteins, respectively (Table 1).31,32 Crystal structures have been solved for M3 and M4 receptors containing antagonists in orthosteric binding sites, whereas no agonist-bound structures are available. A new binding site for muscarinic acetylcholine receptors could provide new opportunities for the understanding of ligand binding and activation processes. We therefore simulated the entire binding processes of the endogenous agonist acetylcholine (ACh) to both M3 and M4 receptors. Surprisingly, the resulting position of ACh bound to the particular receptors revealed an additional new binding site next to the highly conserved Asp (D2.50).33 We also observed that ligand binding leads to the expansion of the binding site.

Table 1. Receptor–ligand (R–L) complexes investigated by MD simulations.

We further inspected over 200 ligand bound GPCR crystal structures and discovered that most ligands were located in traditional orthosteric sites. However, the recently resolved crystal structure of the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor comprised a bound bitopic ligand which extended from this typical orthosteric site to the new ligand binding site found in the present work. This observation strongly suggests that our newly discovered binding site might also exist in other GPCRs. Among these >200 structures, we systematically inspected 39 unique family A GPCRs and found that most of them indeed contain this potential binding site for binding small ligands or extending larger ones from the main orthosteric site. Our findings provide a new opportunity for GPCR drug discovery.

Experimental section

Biological testing

Split luciferase biosensor cAMP assay for measuring activation of Gi protein

Promega's split luciferase based GloSensor cAMP biosensor technology was used to determine GPCR mediated cAMP production. M4 receptor DNA (4 μg) and GloSensor cAMP DNA (4 μg, Promega) were co-transfected into HEK293 T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies). After at least 24 h, the cells were seeded in 384 well white clear bottom plates (Greiner) with DMEM (Life technologies) supplemented with 1% dialyzed FBS at a density of 15–20 000 cells in 20 μl medium per well and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for at least 6 h before analysis. Wells were loaded for 20 min at 37 °C with 20 μl of 2 mg ml–1 Luciferin D sodium salt prepared in HBSS at pH 7.4. All the following steps were carried out at room temperature. To measure agonist activity of the M4 receptor, 10 μl of acetylcholine solutions ranging from 0 to 30 000 μM was added to the cells 15 min before addition of 10 μl of isoproterenol at a final concentration of 200 nM, followed by counting of the plate for chemiluminescence using EnVision (Perkin Elmer) after 15 min. Chemiluminescence intensity was plotted as a function of ACh concentration and normalized to percent acetylcholine with 100% for Emax acetylcholine cAMP inhibition and 0% for the isoproterenol-stimulated cAMP baseline. Data were analyzed using log (ACh) vs. response in GraphPad Prism.

Ca2+ Mobilization assay for measuring activation of Gq protein

To measure ACh-induced G protein coupling to the M3 receptor and the subsequent increase of intracellular calcium ion concentration, HEK293T cells were seeded in a 10 cm dish and incubated overnight. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with 4 μg M3 receptor plasmid and 20 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies). 6 h later, the cells were seeded in 384 well plates at a density of 15 000 cells per well in DMEM containing 1% dialyzed FBS and incubated overnight. On the assay day, the cells were incubated (20 μl per well) for 1 h at 37 °C with Fluo-4 Direct dye (Invitrogen) reconstituted in FLIPR buffer (1 × HBSS, 2.5 mM probenecid, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). After the dye was loaded, the cells were placed in a FLIPRTETRA fluorescence imaging plate reader (Molecular Devices); acetylcholine dilutions were prepared at 3× final concentration in FLIPR buffer and aliquoted into 384 well plates. The fluidics module and plate reader of the FLIPRTETRA were programmed to read baseline fluorescence for 10 s (1 read per s), and then 10 μl of drug/well was added to read for 6 min (1 read per s). Fluorescence in each well was normalized to the average of the first 10 reads (i.e., baseline fluorescence). The maximal fluorescence intensity increase was measured 60 s after acetylcholine addition. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism.

Loop modelling and structural preparations

Loop filling and refinements

The resolved crystal structures of M3 and M4 receptors comprised the engineered receptors and inserted proteins in the intracellular loop ICL2 to facilitate crystallisation. Before starting MD simulations, we removed the corresponding inserted proteins from the M3 and M4 crystal structures and used the loop refinement protocol in Modeller34 V9.10 to reconstruct and refine the ICL2 region. A total of 20 000 loops were generated for each receptor, and the conformation with the lowest DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) score was chosen for receptor construction. Repaired models were submitted to Rosetta V3.4 for loop refinement with kinematic loop modeling methods.35 Kinematic closure (KIC) is an analytic calculation inspired by robotics techniques for rapidly determining possible conformations of linked objects subject to constraints. In the Rosetta KIC implementation, 2N – 6 backbone torsions of an N-residue peptide segment (called non-pivot torsions) were set to values randomly drawn from the Ramachandran space of each residue type, and the remaining 6 phi/psi torsions (called pivot torsions) were solved analytically by KIC.

Protein structure preparations

All protein models were prepared using Schrodinger suite software under the OPLS_2005 force field.36 Hydrogen atoms were added to the repaired crystal structures at physiological pH (7.4) with the PROPKA37 tool to optimize the hydrogen bond network provided by the Protein preparation tool in Schrodinger. Constrained energy minimizations were carried out on the full-atomic models, allowing the maxium RMSD for heavy atoms of 0.4 Å.

Ligand structure preparations

All ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem38 online database. The LigPrep module in Schrodinger 2015 suite software was introduced for geometric optimization by using the OPLS_2005 force field. The ionization state of ligands was calculated with the Epik39 tool employing Hammett and Taft methods in combination with ionization and tautomerization tools.39

Molecular simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations

Membrane systems were built with the membrane building tool g_membed40 in Gromacs with the receptor crystal structure pre-aligned in the OPM (Orientations of Proteins in Membranes) database.41 Pre-equilibrated 120 POPC lipids coupled with 92 000 TIP3P water molecules in a box of ∼ 68 Å × 68 Å × 96 Å were used to build the protein/membrane/water system. We modeled the protein, lipids, water and ions using the CHARMM36 force field.42,43 The ionization states of both protein and the ligand were assigned properly according to the results from Schrodinger software. Ligands were assigned to the CHARMM CgenFF force field.44 The ligand geometry was submitted to the GAUSSIAN 09 program45 for optimization at the Hartree-Fock 6-31G* level when generating force field parameters. The system was gradually heated from 0 K to 310 K followed by a 1 ns initial equilibration at constant volume with the temperature set at 310 K. Both the ligand molecule and protein backbone were restrained by a force constant of 10 kcal mol–1 Å–2 during this step. Next, an additional 40 ns restrained equilibration was performed at constant pressure and temperature (NPT ensemble; 310 K, 1 bar), and the force constant was tapped off gradually from 10 to 0 kcal mol–1. The backbones of the proteins and the heavy atoms of the ligands were restrained during the equilibration steps. All bond lengths to hydrogen atoms were constrained with M-SHAKE. The van der Waals interactions were included using the switching function in the range of 10–12 Å.

Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) summation scheme. All MD simulations were done using Gromacs.46 The simulation parameter files were obtained from the CHARMM-GUI website.47 The MD simulation results were analyzed using Gromacs46 and VMD.48 The solvent accessible surface area was calculated using Gromacs. Figures were prepared using PyMOL and Inkscape.49

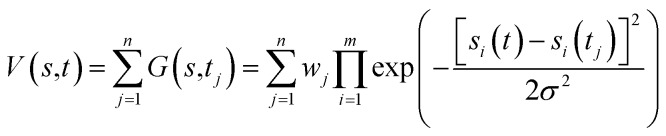

Metadynamics simulations

Free-energy profiles of the systems were calculated using well-tempered metadynamics in Gromacs46 V5.1.4 with Plumed50 V2.2.1 patches. Metadynamics adds a history-dependent potential V(s, t) to accelerate sampling of the specific collective variables (CVs) s (s1, s2, …, sm).51V(s,t) is usually constructed as the sum of multiple Gaussians centered along the trajectory of the collective variables (eqn (1)).

|

1 |

During the simulation, another Gaussian potential, whose location is dictated by the current values of the collective variables, is periodically added to V(s,t).51 In our simulations, distances between the quaternary N atom of ACh and a side chain oxygen of D2.50 were assigned as the collective variables s1, while the width of Gaussians, σ, was set as 0.05. The time interval, τ, was 0.09 ps. Well-tempered metadynamics involves adjusting the height, wj, in a manner that depended on V(s,t) where the initial height of Gaussians w was 0.05 kcal mol–1, the simulation temperature was 310 K, and the sampling temperature ΔT was 298 K. The convergence of our simulations was judged by using the free energy difference between states A and B at 10 ns intervals. Once the results stopped changing over time, the simulation was considered as converged.51

Each metadynamics simulation was performed for 100 ns, and the results were analyzed upon convergence.

Analysis

Interaction fingerprint calculations

The IFP was performed using PLIP software.52 PLIP detects frequent non-covalent protein–ligand interactions including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking, pi-cation interactions, salt bridges, water bridges and halogen bonds.52 We used 200 frames from the final 20 ns MD simulations for the IFP analysis. A plot was generated for the combination of all kinds of interactions. Parameters used for IFP calculations were kept as default.

New ligand binding site predictions and calculations

Inspections for the 39 unique crystal structures of the family A GPCRs were performed using ConCavity,53 a widely used program for ligand site prediction. Both the grid size and resolutions were set to 0.1 Å. The volume of the newly discovered binding site for each receptor was calculated using the POVME54 program. All the other analyses have been done using Gromacs and VMD. Figures were prepared using PyMOL and Inkscape.

Results and discussion

The entrance pathway of M3–ACh

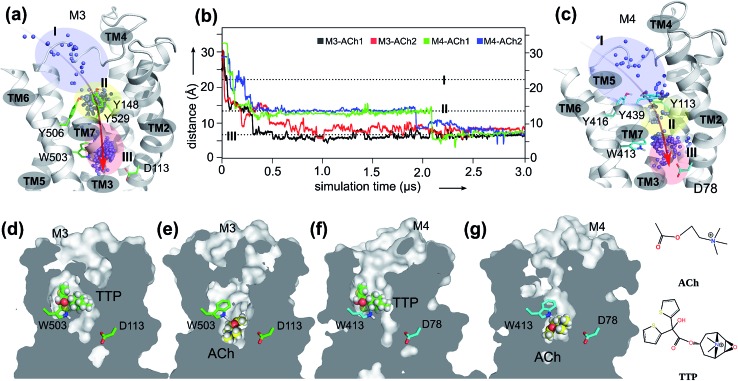

We first present the analysis of eight 3 μs-long MD trajectories, each of which starts with either the antagonist tiotropium (TTP)-bound receptor or the ACh bound at the extracellular vestibule of the receptor (Fig. 1). The crystal structures of both inactive M3 (PDB: ; 4DAJ)31 and M4 (PDB: ; 5DSG)32 receptors were used directly for long time scale MD simulations.

Fig. 1. The orthosteric and novel ligand binding sites of the muscarinic M3 and M4 receptors: (a) view of the M3 receptor showing the overall movement (red arrow) of the ACh molecule from the extracellular vestibule towards the orthosteric site of the receptor during the 3.0 μs MD simulations. Blue dots: mass centers of ACh at different simulation times showing its positional fluctuations within and between the extracellular vestibule, and orthosteric and novel ligand binding sites. Blue-shaded area: extracellular vestibule (zone I). Yellow-shaded area: orthosteric site (zone II). Red-shaded area: novel ligand site (zone III). (b) Time dependence of distance between ACh and oxygen at the sidechain of D2.50 during two independent MD simulations for M3–ACh (black and red) and for M4–ACh (green and blue). The simulations reveal the atomistic details of ACh movements from the extracellular vestibule to the novel ligand binding site of both the M3 and the M4 receptors. (c) View of the M4 receptor showing the overall movement (red arrow) of the ACh molecule from the extracellular vestibule towards the orthosteric site of the receptor during the 3.0 μs MD simulations. Details as in A. (d–g) Cross-sections through the centers of M3 and M4 receptors revealing the final positions of the indicated ligands in different receptor binding sites.

In order to probe the binding mode of ACh in the crystal structure of the M3 receptor,32 we first placed ACh at the entrance of the orthosteric binding pocket. Next, we submitted this M3–ACh structure to all-atom MD simulations. At the beginning of the simulations (Fig. 1a and b, Movie S1†), ACh quickly enters (during 0.1–0.2 μs) the orthosteric site (zone II). Then, ACh is first confined to an aromatic cage characterized by residues Y1483.33–Y5066.51–W5036.48–Y5297.39. The volume of this pocket increases substantially from the initial 86 ± 2 Å3 to 121 ± 3 Å3 at the end of MD simulations. We superimposed a typical conformation of ACh (at ∼0.1 μs snapshot) with the crystal structure of M3–TTP (; 4DAJ)31 and found that the conformation of ACh is identical to that of TTP (Fig. S2†). This supports the hypothesis that the binding site of ACh in the two mAChRs might be the same as observed in the corresponding orthosteric structures (zone II in Fig. 1).32

However, during the 0.5–0.6 μs simulation period, ACh drifts into a much deeper new binding site (zone III) next to the highly conserved residue D1132.50 (Fig. 1a and b). Consequently, the volume of zone III expands from the initial 57 ± 1 Å3 to 148 ± 2 Å3 at the end of the MD simulations. Interestingly, the side chain of the highly conserved W5036.48 undergoes a corresponding flip, leaving space for the entry of the ACh molecule (Movie S1 and Fig. S3†). Such molecular switches have been observed both computationally55 and experimentally56 for adenosine receptors. In contrast, in the antagonist bound M3–TTP system, the antagonist TTP remains stably bound in the orthosteric site (zone II) (Fig. S4†) throughout the entire simulations. The volume of the orthosteric site (zone II) and that of the new binding site (zone III) is 162 ± 2 Å3 and 56 ± 1 Å3, respectively, in this M3–TTP system.

We also investigated the crystal structures of M2 receptors, bound to both an agonist (PDB: 4MQS)57 and to an antagonist (PDB: ; 3UON).58 The highly conserved W4006.48 also underwent molecular switches (Fig. S5†) comparable with that found for the M3 receptor in the present work.

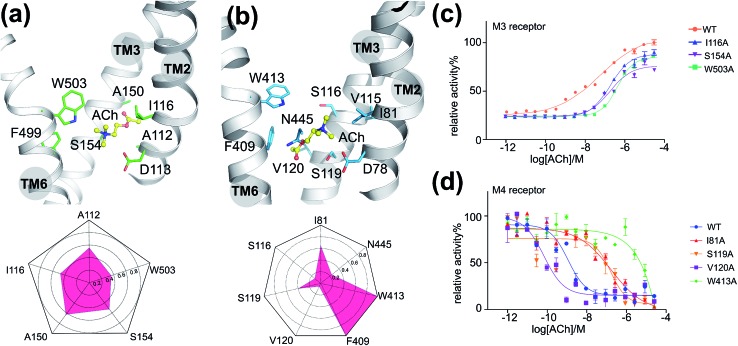

The binding mode of M3–ACh

To validate the above-mentioned findings, we first employed a protein–ligand interaction fingerprint (IFP) analysis for M3–ACh (Fig. 2a) followed by mutagenesis experiments (Fig. 2c and S6†) for M3 receptors. IFP was performed based on the snapshots from the final 20 ns MD simulations. IFP identified that ACh frequently interacts with five residues including A1122.57, I1162.53, A1503.35, S1543.39 and W5036.48. Thus, we next mutated I1162.53, S1543.39 and W5036.48 individually into Ala residues. The signaling assays of the different M3 receptor mutants showed noticeably decreased activities (Table 2). Specifically, the ACh induced activation of Gq by the wild-type (WT) M3 shows an EC50 of 0.5 μM, whereas receptor mutants I1162.53A, S1543.39A and W5036.48A show an EC50 of 1.8 μM, 1.7 μM and 4.0 μM, respectively.

Fig. 2. The interactions between ACh and mAChRs: (a) the final binding position of ACh in the MD simulation of M3–ACh (top) and the protein–ligand interaction fingerprint (IFP) of M3–ACh calculated based on the final 20 ns MD simulations (bottom). Yellow balls-and-sticks: ACh molecule. Green sticks: side chains of M3. (b) The final binding position of ACh in the MD simulation of M4–ACh (top) and the protein–ligand interaction fingerprint (IFP) of M4–ACh calculated based on the final 20 ns MD simulations (bottom). Yellow balls-and-sticks: ACh molecule. Green sticks: side chains of M3. (c) Gq protein activation assay of M3 receptor mutants as a function of ACh concentration. (d) Gi protein activation assay of M4 receptor mutants as a function of ACh concentration.

Table 2. ACh induced activation of G proteins in different mutants of M3 (Gq protein) and M4 receptors (Gi protein).

| M3 | WT | I116A | S154A | W503A | M4 | WT | I81A | S116A | S119A | V120A | F409A | W413A | N445A |

| EC50 (μM) | 0.5 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 4.0 | EC50 (nM) | 1.6 | 174.0 | 192.4 | 23.0 | 0.1 | 6.0 | NA | 12.9 |

The entrance pathway of ACh into the M4 receptor

Furthermore, we extended our investigations to M4 receptors and performed similar MD simulations as before for the M3 receptor. We found that ACh also diffuses into a much deeper binding site of the M4 receptor next to the highly conserved D782.50, however at a different time scale. It first spends a longer period (up to 0.25 μs) in the extracellular vestibule (zone I) before reaching the orthosteric site (zone II) at 0.3–0.4 μs (Movie S2,† Fig. 1b, c, f and g). After stabilizing for a considerable time in this region, ACh continues moving from the orthosteric site (zone II) to the new binding site (zone III) at 1.9–2.1 μs, where it remains firmly bound until the end of the MD simulations. The volumes of zone II and zone III in M4–ACh also change significantly during the MD simulations. The initial volume of zone II of 92 ± 1 Å3 expands to 140 ± 2 Å3 in M4–ACh at the end of MD simulations. The corresponding volume changes in zone III are from 46 ± 1 Å3 to 139 ± 2 Å3. These results are in complete agreement with our previous studies that agonist binding leads to an expansion of the extracellular orthosteric regions.19

The binding mode of M4–ACh

As described for the M3 receptor, we also applied both IFP analysis and mutagenesis experiments to validate our findings for M4–ACh. IFP indicated that there are more residues involved in M4–ACh than in M3–ACh interactions, including I812.53, S1163.36, S1193.39, V1203.40, F4096.44, W4136.48 and N4457.45. We then employed mutagenesis to all these residues individually which led to dramatic effects on the M4 activity in each case (Fig. 2d and Table 2). Specifically, W4136.48A led to a completely inactive M4 mutant towards ACh; the activities of mutants I812.53A and S1163.36A also decreased 100 times compared to that of the WT M4 receptor. In contrast, the mutations of F4096.44A, S1193.39A and N4457.45A show smaller effects with 4–14 fold decreased activities (Fig. S6† and Table 2), while the mutation V1203.40A increased the EC50 by 16 fold.

The binding mode differences between M3–ACh and M4–ACh

Moreover, we found that the final binding positions of ACh in M3 and M4 are different (Fig. 1b and 2a) at the end of MD simulations. In M3–ACh, ACh forms (i) hydrophobic interactions with A1122.57, I1162.53, A1503.35, S1543.39 and W5036.48, and (ii) ionic interactions between its quaternary nitrogen and highly conserved residue D1132.50. The flexible acetyl tail sits in the void space between TM2 and TM3, next to A1503.35. In contrast, ACh flipped by 180 degrees in M4–ACh compared to the binding configuration in M3–ACh: the ester head group comes into contact with V1203.40, F4096.44, W4136.48 and N4457.45, whereas the quaternary nitrogen interacts with I812.53, V1153.35, S1163.36 and S1193.39. Such variations probably stem from the differences in position 3.35: A1503.35 in M3 and V1153.35 in M4. All other residues in the ligand binding sites of M3 and M4 are exactly the same. The smaller A1503.35 in M3 creates more space which can accommodate the ester group but it is still too small to fit the bigger quaternary nitrogen (Fig. 2a). When ACh approaches this region of M3, the ester group can be stabilized between TM2 and TM3. The V1153.35 in M4 takes up more space than A1503.35 in M3. The hydrophobic sidechain of V1153.35 favors the hydrophobic interactions with –CH3 groups from the quaternary nitrogen. The positively charged quaternary nitrogen could be further stabilized in this area by the highly conserved D2.50 through ionic interactions (Fig. 2b) in both M3 and M4.

The kinetic differences in binding M3–ACh and M4–ACh

Noticeably, the time scales for ACh entering the new ligand sites of M3 (0.5 μs) and M4 (2.0 μs) are quite different. To understand these observations, we introduced well-tempered metadynamics MD.

MD simulations are employed to explore the free energy profile of the entire binding processes of ACh for each receptor (Fig. S7†). We defined the distance between the quaternary nitrogen of ACh and the carboxyl group of D2.50 as the collective variable (CV). The results of our metadynamics MD simulations are in complete agreement with our unbiased long-time scale MD simulations, revealing three distinct energy states: the transient locations of ACh in the extracellular vestibule zone I, the orthosteric site zone II, and the final stable new binding site zone III (Fig. 1a and c). Interestingly, we found that the free energy barrier for the movement between zone I and zone II is very low (∼0.1–0.5 kcal mol–1) facilitating the diffusion of ACh from the extracellular vestibule towards the orthosteric site. However, the free energy barrier between zone II and zone III is around 1.6 ± 0.1 kcal mol–1 for M3–ACh and 3.8 ± 0.2 kcal mol–1 for M4–ACh. These large differences in the energy barriers explain why the diffusion of ACh from zone II to zone III takes longer in the M4 than in the M3 receptor. This is probably due to the fact that in position 3.35 in TM3, M4 has a larger residue (Val) than M3 (Ala) which creates a higher steric barrier for ACh to enter the deep binding pocket.

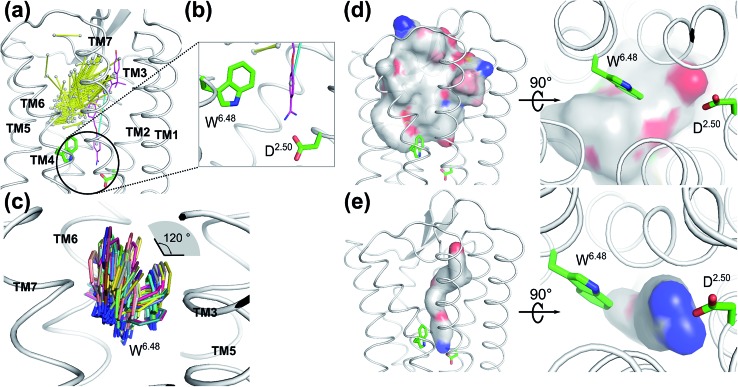

New putative binding sites in crystal structures

To validate whether our newly discovered ligand binding pocket is also applicable to other GPCRs, we analyzed more than 200 crystal structures of family A GPCRs comprising bound ligands (Fig. 3a and S8†) from GPCRDB.59 In the recently deposited crystal structure of the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor (PDB: ; 5X33),60 the benzamidine moiety of the inverse agonist BIIL260 occupies the same new ligand binding site which we have discovered for ACh in the M3 and M4 receptors in this work, contacting D662.50 through an ion-lock interaction (Fig. 3b). Moreover, the highly conserved W2366.48 in the LTB4 receptor was also found undergoing molecular switches induced by the binding of BIIL260 (ref. 60) (Fig. S5b†). Interestingly, the mass center vector of BIIL260 was found at a unique position compared to those of all other ligands resolved in the crystal structures: it directly pointed to the highly conserved D2.50, whereas the mass center vectors of all other ligands are located far away from D2.50. The normalized electrostatic potential surface area (Fig. 3d and e) reveals positively charged surfaces for BIL260 which facilitate the ion lock interaction with D2.50, very similar to that observed for ACh (Fig. 2a and b). In contrast, all other ligands resolved in GPCR crystal structures have either hydrophobic or negatively charged surfaces in the same region, which is very unfavorable to interact with the negatively charged D2.50. This is probably the reason why all the other ligands do not bind to this newly discovered pocket. We propose that a well-designed ligand with both a proper mass center vector and a positively charged head group might be able to move into this new binding pocket of the receptors addressed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Ligands in the vicinity of the classic orthosteric binding site of all family A GPCR crystal structures available in the protein structure databank: (a) ligands observed in the vicinity of the classic orthosteric binding sites of family A GPCR crystal structures after superimposing the receptor coordinates. Yellow stick: each ligand is represented by its mass center of the two heaviest moieties. Purple stick: inverse agonist BIIL260 observed in the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor. Cyan stick: the mass center vector of BIIL260. (b) Extended view of the encircled region in A. An inverse agonist (purple stick) bound to the leukotriene B4 receptor in the crystal structure (PDB: 5X33) is extending to the region which was newly discovered in the present work. (c) Superimposed positions of the highly conserved W6.48 in the crystal structures of family A GPCRs. The χ1 angle of W6.48 can undergo 120° flipping which has a great impact on the volume changes induced by ligand binding to the adjacent orthosteric site. (d) Superposition of the normalized electrostatic potential surfaces of all ligands in the GPCR crystal structures deposited in the structure data bank, excluding ligand BIIL260. Left: side view and right: enlarged bottom view. White: hydrophobic areas. Red: negatively charged areas. Blue: positively charged areas. (e) The normalized electrostatic potential surface for BIIL260 in the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor. White: hydrophobic area. Red: negatively charged area. Blue: positively charged area.

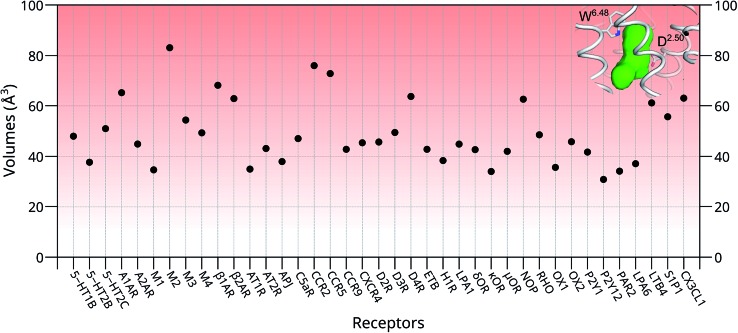

New putative ligand binding sites in other GPCRs

To further investigate whether our newly discovered binding sites of the M3 and M4 receptors are also present in other GPCRs, we inspected 39 unique crystal structures of family A GPCRs (Fig. S9† and 4). Here, we used ConCavity53 for ligand site prediction and found that all investigated GPCRs also potentially have an additional ligand binding site between positions 6.48 and 2.50. To further characterize this binding site for each receptor, we calculated the volume of this region using the POVME tool.54 The calculation indicates that most receptors have a reasonable volume of 30–85 Å3 for this newly discovered binding site. Specifically, 5-HT2B, M1, AT1R, APJ, H1R, κOR, OX1, P2Y12, PAR2 and LPA6 receptors all have a relatively small binding site, with volumes in the range of 30–40 Å3. In contrast, the volumes of the putative additional binding pockets in 5-HT1B, 5-HT2C, AT2R, M3, M4, C5aR, CCR9, CXCR4, D2R, D3R, ETB, LPA1, δOR, μOR, RHO, OX2, P2Y1 and S1P1 are in the range of 40–60 Å3. Finally, receptors A1AR, M2, β1AR, β2AR, CCR2, CCR5, D4R, NOP, LTB4 and CX3CL1 have distinct larger putative ligand binding pockets, in the range of 60–85 Å3 which is the size of two water molecules or a small ligand. However, the volume of this pocket in each receptor might be substantially enlarged upon agonist binding as indicated by our MD simulation in this work.

Fig. 4. The volumes of the newly discovered putative binding sites in the absence of ligands in 39 unique structures of family A GPCRs. Green region: the volume of the newly discovered binding site located between the highly conserved W6.48 and D2.50 of the M4 receptor. Most of the proposed empty binding pockets have volumes >40 Å3.

Interestingly, the final position of the sidechain of W2366.48 observed in LTB4 is identical to that of the corresponding W4006.48 in the agonist bound activated M2 receptor (Fig. S5†): both sidechains underwent rotamer changes. The superimposed structures of all family A GPCRs in the data bank indicate that the χ1 angles of W6.48 can undergo changes as large as 120° (Fig. 3C).

Although these new potential orthosteric sites are small in size, their volumes can be increased accordingly after the rotation of the highly conserved W6.48 upon proper ligand binding. This is further confirmed by our previously performed long time scale MD simulations on FPR1,61 S1P1R62 and A2AR,55 of which the volumes for newly discovered binding sites increased from 46 ± 1 Å3 to 132 ± 2 Å3, 58 ± 3 Å3 to 163 ± 3 Å3 and 51 ± 2 Å3 to 156 ± 2 Å3, respectively, after the flipping of the corresponding W6.48 sidechains.

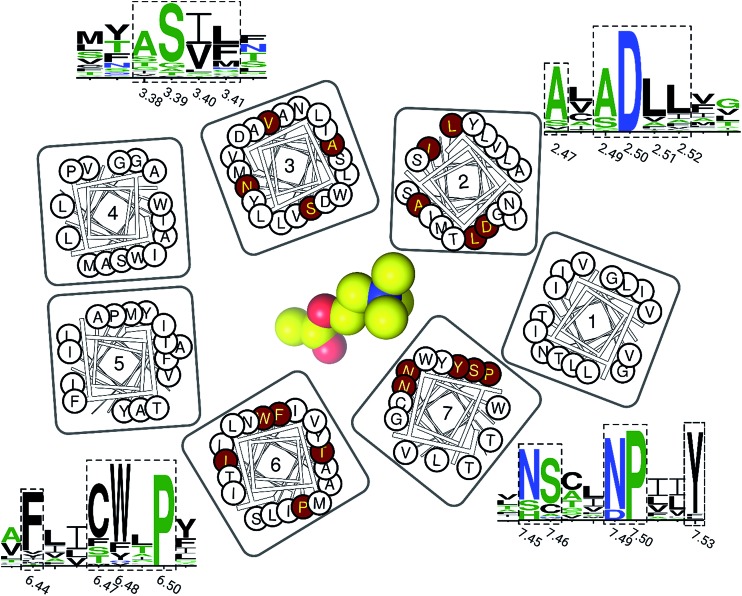

Finally, we inspected the conservations of residues in this newly discovered cavity, based on all resolved crystal structures of family A GPCRs (Fig. 5). We found that most residues of this binding pocket are highly conserved, including residues in positions 2.47, 2.49, 2.50, 2.51, 2.52, 3.38, 3.39, 3.40, 3.41, 6.44, 6.47, 6.48, 4.50, 7.45, 7.46, 7.49 and 7.50. This observation indicates that this newly discovered binding pocket indeed exists and is highly conserved in most resolved structures of family A GPCRs.

Fig. 5. The residue conservations of the newly discovered binding pocket. The logos of conserved residues (highlighted in dashed rectangles) are based on the multiple sequence alignment on all resolved crystal structures of family A GPCRs. The height of each single letter in the depicted sequence segments scales with its conservation at the corresponding position. Their positions on TM helices are highlighted in red circles in the residue diagrams. An ACh molecule is represented as a yellow sphere to show its relative position.

Conclusions

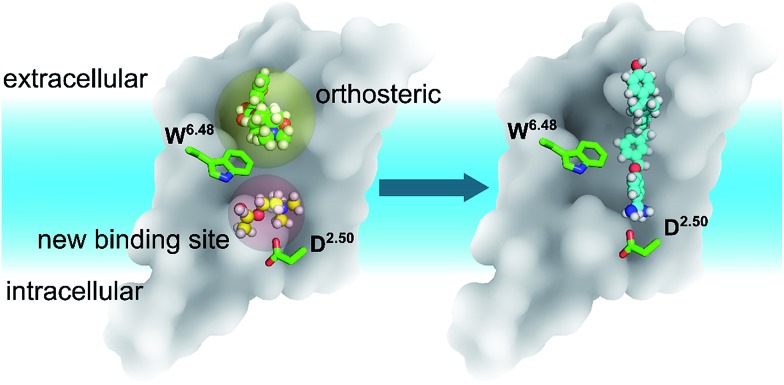

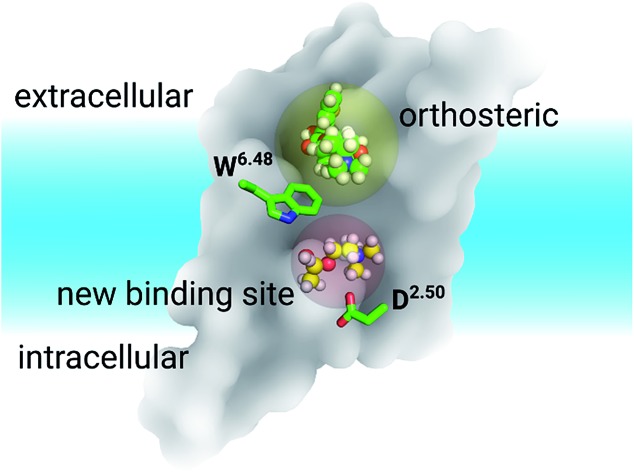

In summary, discovering a new ligand binding site for a particular protein is an essential first step for structure-based drug discovery. Computer modelling is a very useful tool for modern structural biology. By using MD simulations coupled with mutagenesis experiments, we identified a potential new binding pocket for the endogenous agonist ACh in M3 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (Fig. 6), whereas the antagonist molecule TTP is trapped in the traditional orthosteric binding site. The small and flexible ACh diffuses deeper inside the receptor towards a new binding site next to the highly conserved residue D2.50. Molecular switches take place at the highly conserved W6.48 induced by ligand binding. As the volumes of both orthosteric and new sites expand upon the binding of ACh in the case of the M3 and M4 receptors, we predict similar volume changes in the other putative binding sites upon ligand binding.

Fig. 6. The relative positions of the classic orthosteric site (left panel, yellow shaded sphere) and the newly discovered ligand binding site (left panel, red shaded sphere) located between W6.48 and D2.50. A new drug molecule (right panel) can be designed, based on the newly discovered site in this work. Green balls-and-sticks: the TTP molecule observed in the crystal structures of M3 & M4 receptors. Yellow balls-and-sticks: ACh observed in this work. Cyan stick: an inverse agonist observed in the crystal structure of the LTB4 receptor.

In our present work, we systematically inspected the binding sites of all published family A GPCR crystal structures. We discovered that most residues, forming this newly discovered pocket, are highly conserved. We also found that most GPCRs potentially comprise these newly discovered binding sites, which have been confirmed by both a recently resolved crystal structure of LTB4 and computer modeling. Our newly uncovered ligand binding sites open new opportunities for GPCR drug discovery and design.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support from the Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling in Warsaw (grants GB70-3 & GB71-3 to SY and G07-13 & GA65-23 to SF), the National Center of Science, Poland (grant 2013/08/M/ST6/00788) to SF), the European Community (project SynSignal, grant no. FP7-KBBE-2013-613879) and the EPFL to HV is acknowledged. Additional funding came from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation to KP. HV and SF participated in the European COST Action CM1207 (GLISTEN). KP is the John H. Hord Professor of Pharmacology. Dedicated to Prof. Horst Vogel on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8sc01680a

References

- Skolnick J., Gao M., Roy A., Srinivasan B., Zhou H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti-Solano M., Schmidt D., Kolb P., Selent J. Drug discovery today. 2016;21:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Li B., Cheng L. T., Zhou S., McCammon J. A., Che J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:753–765. doi: 10.1021/ct500867u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stank A., Kokh D. B., Fuller J. C., Wade R. C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016;49:809–815. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague S. J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2003;2:527–541. doi: 10.1038/nrd1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Pan A. C., Dror R. O., Mocking T., Liu R., Heitman L. H., Shaw D. E., IJzerman A. P. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016;89:485–491. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.102657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser A. S., Attwood M. M., Rask-Andersen M., Schioth H. B., Gloriam D. E. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson S. C., McMahon C., Kruse A. C. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018;47:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070317-032931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziarek J. J., Peterson F. C., Lytle B. L., Volkman B. F. Methods Enzymol. 2011;493:241–275. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M., Prakash P., Gorfe A. A. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2016;48:3–10. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Lakkaraju S. K., Coop A., MacKerell Jr A. D. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:11897–11904. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b09351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkaraju S. K., Lemkul J. A., Huang J., MacKerell Jr A. D. J. Comput. Chem. 2016;37:416–425. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eps N., Caro L. N., Morizumi T., Kusnetzow A. K., Szczepek M., Hofmann K. P., Bayburt T. H., Sligar S. G., Ernst O. P., Hubbell W. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E3268–E3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620405114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S., Jovancevic N., Gelis L., Pietsch S., Hatt H., Gerwert K. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16007. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilger D., Masureel M., Kobilka B. K. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:4–12. doi: 10.1038/s41594-017-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Van Eps N., Zimmer M., Ernst O. P., Prosser R. S. Nature. 2016;533:265–268. doi: 10.1038/nature17668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Chun E., Thompson A. A., Chubukov P., Xu F., Katritch V., Han G. W., Roth C. B., Heitman L. H., IJzerman A. P., Cherezov V., Stevens R. C. Science. 2012;337:232–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1219218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Gao Z. G., Zhang K., Kiselev E., Crane S., Wang J., Paoletta S., Yi C., Ma L., Zhang W., Han G. W., Liu H., Cherezov V., Katritch V., Jiang H., Stevens R. C., Jacobson K. A., Zhao Q., Wu B. Nature. 2015;520:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chan H. C., Vogel H., Filipek S., Stevens R. C., Palczewski K. Angew. Chem. 2016;55:10331–10335. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A., Yano J., Hirozane Y., Kefala G., Gruswitz F., Snell G., Lane W., Ivetac A., Aertgeerts K., Nguyen J., Jennings A., Okada K. Nature. 2014;513:124–127. doi: 10.1038/nature13494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald C., Rappas M., Kean J., Dore A. S., Errey J. C., Bennett K., Deflorian F., Christopher J. A., Jazayeri A., Mason J. S., Congreve M., Cooke R. M., Marshall F. H. Nature. 2016;540:462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson N., Rappas M., Dore A. S., Brown J., Bottegoni G., Koglin M., Cansfield J., Jazayeri A., Cooke R. M., Marshall F. H. Nature. 2018;553:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature25025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo M., Masetti M., Bottegoni G., Cavalli A. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:4035–4061. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbadin D., Moro S. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:372–376. doi: 10.1021/ci400766b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino K. A., Filizola M. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1705:351–364. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7465-8_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror R. O., Pan A. C., Arlow D. H., Borhani D. W., Maragakis P., Shan Y., Xu H., Shaw D. E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:13118–13123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104614108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A., Wittmann H. J., Seifert R. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;38:717–732. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., McCammon J. A. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016;41:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A. S., Elgeti M., Zachariae U., Grubmuller H., Hofmann K. P., Scheerer P., Hildebrand P. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11244–11247. doi: 10.1021/ja5055109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A. S., Zachariae U., Grubmuller H., Hofmann K. P., Scheerer P., Hildebrand P. W. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. C., Hu J., Pan A. C., Arlow D. H., Rosenbaum D. M., Rosemond E., Green H. F., Liu T., Chae P. S., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E., Weis W. I., Wess J., Kobilka B. K. Nature. 2012;482:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature10867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal D. M., Sun B., Feng D., Nawaratne V., Leach K., Felder C. C., Bures M. G., Evans D. A., Weis W. I., Bachhawat P., Kobilka T. S., Sexton P. M., Kobilka B. K., Christopoulos A. Nature. 2016;531:335–340. doi: 10.1038/nature17188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isberg V., de Graaf C., Bortolato A., Cherezov V., Katritch V., Marshall F. H., Mordalski S., Pin J. P., Stevens R. C., Vriend G., Gloriam D. E. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;36:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M. A., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M. Y., Pieper U. and Sali A., Current protocols in protein science, ed. John E. Coligan, 2007, ch. 2, Unit 2 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell D. J., Coutsias E. A., Kortemme T. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:551–552. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivakumar D., Williams J., Wu Y. J., Damm W., Shelley J., Sherman W. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:1509–1519. doi: 10.1021/ct900587b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondergaard C. R., Olsson M. H. M., Rostkowski M., Jensen J. H. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2284–2295. doi: 10.1021/ct200133y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L., Xiao J. W., Suzek T. O., Zhang J., Wang J. Y., Zhou Z. G., Han L. Y., Karapetyan K., Dracheva S., Shoemaker B. A., Bolton E., Gindulyte A., Bryant S. H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D400–D412. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J. R., Calkins D., Sullivan A. P., Shelley J. C. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2010;24:591–604. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. G., Hoefling M., Aponte-Santamaria C., Grubmuller H., Groenhof G. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:2169–2174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomize A. L., Pogozheva I. D., Mosberg H. I. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:918–929. doi: 10.1021/ci2000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauda J. B., Venable R. M., Freites J. A., O'Connor J. W., Tobias D. J., Mondragon-Ramirez C., Vorobyov I., MacKerell A. D., Pastor R. W. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Rauscher S., Nawrocki G., Ran T., Feig M., de Groot B. L., Grubmuller H., MacKerell Jr A. D. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K., Raman E. P., MacKerell Jr A. D. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:3155–3168. doi: 10.1021/ci3003649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H. P., Izmaylov A. F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J. L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery Jr J. A., Peralta J. E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J. J., Brothers E., Kudin K. N., Staroverov V. N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J. C., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J. M., Klene M., Knox J. E., Cross J. B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R. E., Yazyev O., Austin A. J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J. W., Martin R. L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V. G., Voth G. A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J. J., Dapprich S., Daniels A. D., Farkas O., Foresman J. B., Ortiz J. V., Cioslowski J. and Fox D. J., Gaussian 09, Revision A.1, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

- Pronk S., Pall S., Schulz R., Larsson P., Bjelkmar P., Apostolov R., Shirts M. R., Smith J. C., Kasson P. M., van der Spoel D., Hess B., Lindahl E. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V. G., Im W. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chan H. C., Filipek S., Vogel H. Structure. 2016;24:2041–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Bussi G., Camilloni C., Provasi D., Raiteri P., Donadio D., Marinelli F., Pietrucci F., Broglia R. A., Parrinello M. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009;180:1961–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Barducci A., Bussi G., Parrinello M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salentin S., Schreiber S., Haupt V. J., Adasme M. F., Schroeder M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W443–W447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capra J. A., Laskowski R. A., Thornton J. M., Singh M., Funkhouser T. A. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J. D., Votapka L., Sorensen J., Amaro R. E. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014;10:5047–5056. doi: 10.1021/ct500381c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Hu Z., Filipek S., Vogel H. Angew. Chem. 2014;54:556–559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy M. T., Lee M. Y., Gao Z. G., White K. L., Didenko T., Horst R., Audet M., Stanczak P., McClary K. M., Han G. W., Jacobson K. A., Stevens R. C., Wuthrich K. Cell. 2018;172:68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. C., Ring A. M., Manglik A., Hu J., Hu K., Eitel K., Hubner H., Pardon E., Valant C., Sexton P. M., Christopoulos A., Felder C. C., Gmeiner P., Steyaert J., Weis W. I., Garcia K. C., Wess J., Kobilka B. K. Nature. 2013;504:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nature12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga K., Kruse A. C., Asada H., Yurugi-Kobayashi T., Shiroishi M., Zhang C., Weis W. I., Okada T., Kobilka B. K., Haga T., Kobayashi T. Nature. 2012;482:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isberg V., Mordalski S., Munk C., Rataj K., Harpsoe K., Hauser A. S., Vroling B., Bojarski A. J., Vriend G., Gloriam D. E. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D356–D364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T., Okuno T., Hirata K., Yamashita K., Kawano Y., Yamamoto M., Hato M., Nakamura M., Shimizu T., Yokomizo T., Miyano M., Yokoyama S. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018;14:262–269. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Ghoshdastider U., Latek D., Trzaskowski B., Debinski A., S. Filipek PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.2174/092986712799320556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Wu R., Latek D., Trzaskowski B., Filipek S. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.