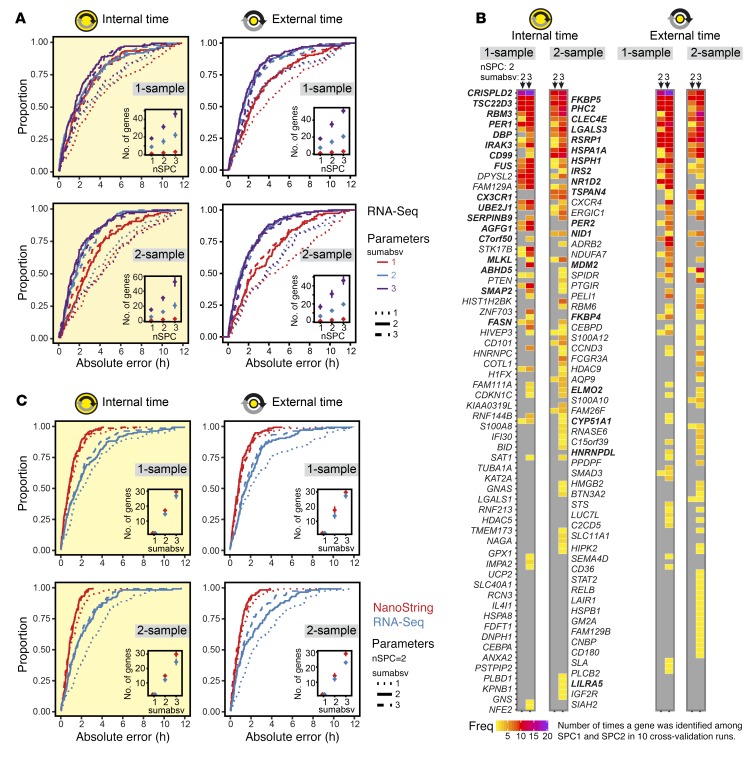

Figure 2. Extraction of candidate biomarkers and migration to the NanoString platform.

(A) Cumulative frequency distributions of the absolute prediction errors for 4 types of ZeitZeiger internal cross-validation predictors of either internal or external time by 1- or 2-sample mRNA abundance profiles (n = 136). Each type of predictor was built for 9 combinations of the ZeitZeiger parameters sumabsv = {1, 2, 3} and nSPC = {1, 2, 3}. Insets show the average number of genes ± SD in the internal cross-validation predictors as a function of sumabsv and nSPC. (B) Global gene sets of the best-performing internal cross-validation predictors shown in A. Each column depicts a predictor defined by the type of the predictor variable (internal or external time), the format of the data input (1-sample or 2-sample), and the ZeitZeiger parameters (sumabsv, nSPC). Each predictor includes 10 leave-one-subject-out cross-validation runs, i.e., 10 gene sets. The ordering (from top to bottom) and the colors indicate how often a gene was identified as time-telling and assigned to SPC1, SPC2, or both among those 10 gene sets. Thirty-four genes that showed a high frequency of identification among cross-validation runs and were consistently identified across the best-performing predictors were chosen as a candidate biomarker set for internal time and migrated to the NanoString platform (highlighted in bold font). (C) Impact of platform migration on the performance of the candidate biomarkers for internal time. Given are cumulative frequency distributions of the absolute prediction errors of ZeitZeiger internal cross-validation models built on either RNA-Seq (blue) or NanoString data (red) obtained from the same RNA preparations. Platform comparison was performed for 4 types of predictors of either internal or external time by 1- or 2-sample mRNA abundance profiles (n = 136).