Abstract

Strongyloidiasis is a well-known parasitic infection endemic in tropical and subtropical areas of the world. While most infected individuals are asymptomatic, strongyloidiasis-related glomerulopathy has not been well documented. We present a case of disseminated strongyloidiasis in a patient with minimal change nephrotic syndrome treated with high-dose corticosteroids. The remission of nephrotic syndrome after treatment of strongyloidiasis suggests a possible causal relationship between Strongyloides and nephrotic syndrome.

Keywords: Strongyloidiasis, Strongyloides stercoralis, Nephrotic syndrome

Introduction

Strongyloidiasis is a common parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. it is endemic in tropical and subtropical countries including Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe with prevalence rates reported as high as 30$. Under immunological conditions, intestinal infection with this nematode is usually associated with asymptomatic carrier status. However, disseminated strongyloidiasis occurs with immune suppression and has been studied in patients with organ transplantation, leukaemia, and human immunodeficiency virus. While parasite-related glomerular diseases have been studied, strongyloidiasis-related glomerulopathy has not been well documented. Several case reports have suggested a causal relationship between strongyloidiasis and nephrotic syndrome but the relationship remains controversial. We review the literature and report a case of disseminated strongyloidiasis in a patient with minimal change nephrotic syndrome treated with high-dose corticosteroids. The remission of nephrotic syndrome after treatment of strongyloidiasis postulates that the nephrotic syndrome could have been related to the Strongyloides immune complex deposition.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Hispanic male with medical history of hypertension, who was originally from Puerto Rico but had moved to the USA in adulthood, presented with nausea, bloating, and generalized oedema for 1 month in December 2014. He did not have fever, chills, cough, or diarrhoea. He was a non-smoker, and did not drink alcohol or use illicit drugs.

On initial physical examination, he was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 168/100 mm Hg and heart rate of 80 beats/min. He had periorbital swelling and bilateral lower extremity oedema. His cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal, and neurological examinations were otherwise unremarkable.

Initial laboratory tests showed a leucocyte count of 12,800/µL with 15.5$ eosinophilia, serum creatinine of 2.2 mg/dL, serum albumin of 2.3 g/dL, and total proteinuria of 11.1 g/day. HBs antigen and anti-HCV antibody were negative and abdominal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys. Electrocardiogram and chest radiograph were normal.

A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed. Light microscopy revealed 13 glomeruli. Electron microscopy revealed complete podocyte foot process effacement and immunofluorescence revealed linear, segmental to global GBM staining for IgG and kappa of unclear significance. At this point, idiopathic minimal change disease was suspected, as no clear aetiology or inciting factor was identified. The patient was started on prednisone 80 mg daily and treatment resulted in improvement of proteinuria to 0.47 g/day by day 33.

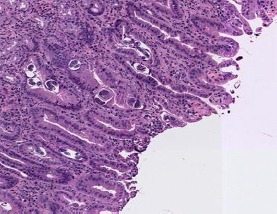

A month following initiation of corticosteroids, the patient was evaluated for loss of appetite, fatigue, minimally productive cough, vomiting, and diarrhoea. The diarrhoea was non-bloody and watery, occurring after meals. Chest radiograph revealed a new interstitial reticulonodular pattern of unclear significance. Abdominal radiograph revealed abnormal gas collection thought to be due to small bowel obstruction that was managed conservatively. Due to the development of melena, he underwent diagnostic endoscopy which revealed oedematous gastric and duodenal mucosa (Fig. 1). Biopsy of lesions showed chronic active gastritis with the presence of larvae/nematode within the mucosa, consistent with diagnosis of strongyloidiasis (Fig. 2, 3). The patient was treated with 200 µg/kg ivermectin for 5 days and his diarrhoea promptly improved. No ova or parasites were noted in the stool 2 weeks later. Based on a literature review, it was hypothesized that his nephrotic syndrome and minimal change disease may have been in fact caused by Strongyloides and only unmasked during steroid therapy. It was therefore decided that his proteinuria would be closely followed off steroids, and did actually resolve 3 months after infection eradication.

Fig. 1.

Erosions in gastric mucosa.

Fig. 2.

Biopsy showing Strongyloides nematode and ovum.

Fig. 3.

High-power view of nematode on biopsy.

Discussion

S. stercoralis is usually associated with an asymptomatic carrier state. However, under certain conditions, most notably a compromise of host immunity, fulminant disease may develop with greater than 50$ mortality despite adequate treatment [1]. In symptomatic patients, the most common presentations are fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea. In disseminated disease, the nematode can affect virtually every organ, including the brain, lungs, and kidneys [2].

Cases of strongyloidiasis-associated glomerulopathy have rarely been reported. An extensive review of the medical literature has identified 7 other cases of strongyloidiasis associated with nephrotic syndrome (Table 1). In 7 out of 8 cases, the patient's initial presentation was with features of nephrotic syndrome, and all patients were found to have minimal change disease on renal biopsy. In the majority of cases, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed first, and following the initiation of steroids, only then was Strongyloides unmasked. Corticosteroid therapy could alter immunological mechanisms and play and important role in the abrupt exacerbation of Strongyloides. Interestingly, Hsieh et al. [3] reported a patient with initial manifestations strongly related to Strongyloidiasis who later developed nephrotic syndrome. Heavy proteinuria resolved following treatment with anthelmintic therapy without use of steroids, suggestive of a possible causal relationship between S. stercoralis infection and minimal change disease. The pathogenesis of Strongyloides-associated glomerulopathy is postulated to be due to immune complex deposition, as supported by the fact that the Strongyloides antigen has been demonstrated in renal biopsy tissue [4].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of strongyloidiasis-associated nephropathy in the literature review

| Author | Age, years/sex | Prior diagnosis of strongyloidiasis | Initial presenting symptoms | Duration of steroid use | Manifestations of strongyloidiasis | Kidney biopsy | Antihelmintic therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present case | 67/M | No | Generalized oedema | 1 month | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea | MCD | Ivermectin | Remission |

| Miyazaki et al. [9], 2010 | 69/M | No | Generalized oedema | >4 months | Diarrhoea, weight loss | MCD | Ivermectin | Died |

| Hsieh et al. [3], 2006 | 72/M | Yes | Cough, abdominal pain, diarrhoea | Nil | Presenting symptoms | MCD | Ivermectin | Remission |

| Morimoto et al. [10], 2002 | 60/F | No | Generalized oedema | 2 months | Vomiting, paralytic ileus | MCD | - | Died |

| Yee et al. [11], 1999 | 55/M | No | Generalized oedema | 6 weeks | Epigastralgia, vomiting, diarrhoea | MCD | Thiabendazole | Remission |

| Wong et al. [12], 1998 | 42/F | No | Generalized oedema | 6 weeks | Brain abscess, gram-negative sepsis | (Biopsy done 4 months after treatment) | ||

| MCD | Thiabendazole, albendazole | Remission | ||||||

| Mori et al. [13], 1998 | 62/M | No | Generalized oedema | 1 month | Epigastralgia, paralytic ileus | MCD | Thiabendazole | Remission |

MCD, minimal change disease.

A common finding among the reported cases is the presence of peripheral eosinophilia. In our patient, he had eosinophilia but this was not a persistent finding. Studies have shown that eosinophilia is not always present, usually fluctuating and even absent in more than 50$ of patients with severe infection [5]. Hence, a high index of suspicion is required for prompt diagnosis.

The diagnosis of Strongyloides can be confirmed by the presence of larvae in stool or duodenal aspirate. Duodenal biopsy usually shows blunting of the villi and invasion by the parasite and ova. The standard first-line therapy for Strongyloides infection includes thiabendazole, ivermectin, and albendazole, with comparable eradication rates [6, 7, 8].

Conclusions

When a patient who resides in an endemic part of the world presents with nephrotic syndrome, a thorough review of systems should be done to rule out active Strongyloides infection. Our literature review suggests that active symptoms are only unmasked after steroids are initiated, so ongoing monitoring of any new or chronic symptoms is vital, especially as the usual treatment of nephrotic syndrome can cause lethal disseminated Strongyloides infection. To date, there is 1 published case of symptomatic Strongyloides with subsequent development of nephrotic syndrome that remitted with antibiotic treatment, and multiple other cases where infectious symptoms were unmasked by nephrotic syndrome treatment. Due to this increasingly reported association, more research is warranted to investigate for a clear causal relationship.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chaudhary K, Smith RJ, Himelright IM, Baddour LM. Case report: purpura in disseminated strongyloidiasis. Am J Med Sci. 1994 Sep;308((3)):186–91. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199409000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owor R, Wamukota WM. A fatal case of strongyloidiasis with Strongyloides larvae in the meninges. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1976;70((5–6)):497–9. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh YP, Wen YK, Chen ML. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome in association with strongyloidiasis. Clin Nephrol. 2006 Dec;66((6)):459–63. doi: 10.5414/cnp66459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churg J, Sobin LH. Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin; 1982. Renal Disease: Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purtilo DT, Meyers WM, Connor DH. Fatal strongyloidiasis in immunosuppressed patients. Am J Med. 1974 Apr;56((4)):488–93. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulmer HS, Huempfner HR. Intestinal helminths in eastern Kentucky: A survey in three rural countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1965 Mar;14((2)):269–75. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbard DW, Morgan PM, Yaeger RG, Unglaub WG, Hood MW, Willis RA. Intestinal parasite survey of kindergarten children in New Orleans. Pediatr Res. 1974 Jun;8((6)):652–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eveland LK, Kenney M, Yermakov V. The value of routine screening for intestinal parasites. Am J Public Health. 1975 Dec;65((12)):1326–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.65.12.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyazaki M, Tamura M, Kabashima N, Serino R, Shibata T, Miyamoto T, et al. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome in a patient with strongyloidiasis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010 Aug;14((4)):367–71. doi: 10.1007/s10157-010-0273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morimoto J, Kaneoka H, Sasatomi Y, Sato YN, Murata T, Ogahara S, et al. Disseminated strongyloidiasis in nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2002 May;57((5)):398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yee YK, Lam CS, Yung CY, Que TL, Kwan TH, Au TC, Szeto ML. Strongyloidiasis as a Possible Cause of Nephrotic Syndrome. Am J of Kidney Dis. 1999 Jun;33((6)):e4. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong TY, Szeto CC, Lai FF, Mak CK, Li PK. Nephrotic syndrome in strongyloidiasis: remission after eradication with anthelmintic agents. Nephron. 1998;79((3)):333–6. doi: 10.1159/000045058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori S, Konishi T, Matsuoka K, Deguchi M, Ohta M, Mizuno O, et al. Strongyloidiasis associated with nephrotic syndrome. Intern Med. 1998 Jul;37((7)):606–10. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]