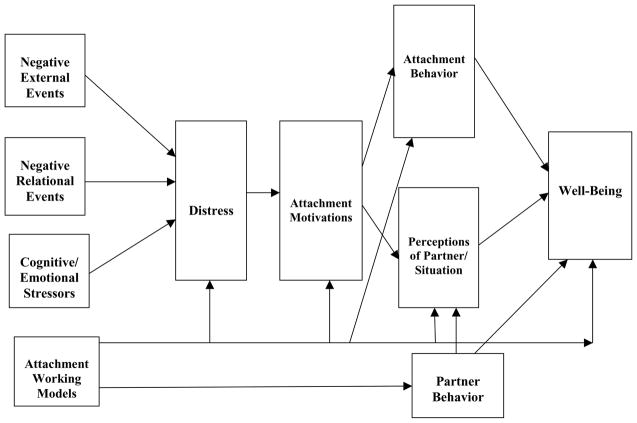

Figure 1.

The Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model [7] has two components: a normative (species-typical) component, and an individual difference component. From a normative perspective, the attachment system is activated (turned on) by three types of events: (1) negative external events (e.g., dangerous/threatening situations), (2) negative relational events (e.g., relationship conflict, separation, abandonment), and (3) cognitive/emotional stressors (e.g., ruminating about negative events). Each one elicits distress in most people. Distress, in turn, triggers species-typical attachment motivations to seek proximity, support, and/or reassurance from attachment figures (e.g., parents, close friends, romantic partners). These motivations then launch specific attachment behaviors designed to reduce or regulate distress, which then influences perceptions of the partner and/or the current situation. Perceptions of the partner/situation, however, are also influenced by how the partner behaves in the current situation. The specific attachment behaviors that an individual displays, and the partner/relationship perceptions s/he has, are guided by his/her working models (see below). These behaviors and perceptions, in turn, affect an individual’s relational and personal well-being in response to the stressful situation.

Attachment working models can affect any stage of the model, as shown by the lines running from attachment working models to each model stage. For example, working models can influence how distressed individuals feel in response to a negative or stressful event, and they can determine which attachment motivations are evoked when distress is experienced. Working models can also affect the attachment behaviors that individuals display when attachment motivations are triggered, how they perceive their partners in the situation, and how their partners behave toward them. Each of these pathways can impact the quality of relational and personal well-being that is experienced during or after encountering the stressful event.

From an individual difference perspective, the model proposes that individuals who have different attachment orientations should respond differently when they are exposed to certain kinds of distressing situations. For example, when highly anxious individuals encounter stressful events that threaten or call into question the quality or stability of their romantic relationships, they should be keenly aware of their distress and seek immediate help/support from their romantic partners. In light of the conflicted nature of their working models, however, anxious individuals should be strongly motivated to reduce distress by increasing proximity (including emotional closeness) with their partners. This should be exacerbated by their reliance on emotion-focused/hyperactivating coping strategies [7, 21], which direct their attention toward the source of distress and lead them to ruminate about possible negative outcomes. Such coping strategies also direct their attention away from figuring out how to resolve the stressor/problem, which keeps their attachment systems activated. As a result, the attachment behaviors that highly anxious individuals enact center on intense, obsessive proximity/support/reassurance-seeking from their partners, which often do not diminish their distress. Over time, the romantic partners of anxious individuals are likely to tire and become frustrated from continually having to offer reassurance/support, and these reactions may be construed by anxious individuals as signs of further rejection. Highly anxious individuals should also perceive their partner’s intentions, motives, and actions less benevolently during the stressful situation, underestimating the care/support that their partners provide (or are willing to provide). These negative perceptions should, in turn, generate lower relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.

When confronting stressful events, especially those that threatened their autonomy and independence, highly avoidant individuals might not be fully aware of how distressed they are, and they should neither want nor seek help or support from their partners unless they feel overwhelmed. Given their negative, cynical working models, avoidant individuals should be motivated to reduce or contain the distress they feel by being self-reliant, which allows them to reestablish independence, autonomy, and control in the stressful situation. This should be facilitated by their use of avoidant/deactivating coping strategies [7, 21], which suppress awareness of their distress, attachment needs, and attachment behaviors, at least in the short-term. Avoidant individuals should engage in attachment behaviors that allow some contact with their partners, but at a safe, emotionally comfortable distance and on terms they dictate. The partners of avoidant individuals should, in turn, offer and provide lower levels of reassurance and support, which avoidant individuals should prefer, but may also view as further rejection. Avoidant individuals should also view their partner’s intentions, motives, and behaviors in the stressful situation less benevolently, leading them to underestimate the amount of care and support their partners have given them (or are willing to provide). These negative perceptions should culminate in lower relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.

When highly secure individuals (i.e., those who score low on anxiety and avoidance) experience distressing situations, they ought to realize that they are upset and may need help or support from their partners, depending on the nature of the stressor and the knowledge and skills they have to address it. In view of their positive working models, secure individuals should be motivated to manage distress by drawing closer to their partners (physically and emotionally) in order to increase closeness and intimacy with them. This should be facilitated by their adoption of problem-focused coping strategies [7, 21], which permit secure individuals to resolve most problems constructively with appropriate assistance from their partners. The attachment behaviors that highly secure individuals should enact involve requesting or seeking proximity, comfort, or support from their partners, which helps them dissipate distress so they can pursue other important life tasks. The partners of highly secure individuals, in turn, should respond in more positive and constructive ways when secure individuals request comfort/care/support from them (unless their partners happen to be insecurely attached). In addition, highly secure individuals should perceive their partner’s intentions, motives, and actions in the situation more benevolently. These positive perceptions should result in better relational and personal well-being during and/or following the stressful event.