Abstract

Background:

A wide variety of drugs have the potential to affect immune and inflammatory responses of periodontium. A class of antidepressant drug, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, has shown anti-inflammatory function. The aim of the present study is to explore the effect of desvenlafaxine on clinical periodontal parameters in patients with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

The patients were divided into two groups as follows: test group (n = 63) comprised of participants on 50 mg once-daily dose of desvenlafaxine for ≥2 months and control group (n = 72) included participants who were yet to be prescribed medication for depression. Periodontal parameters of both the groups were analyzed and compared statistically.

Results:

Participants taking desvenlafaxine revealed lower values of periodontal parameters as compared to those in control group. The number of pockets with greater depth and clinical attachment loss was greater in control group.

Conclusion:

In our study, patients on desvenlafaxine were associated with less pocket depth and bleeding on probing.

Keywords: Antidepressant, chronic periodontitis, desvenlafaxine, observational study

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation and destruction of periodontal tissues are largely considered to result from the response of a susceptible host to microbial biofilm-containing pathogenic bacteria.[1] Periodonto-pathogens induce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by immune cells, which in turn stimulates osteoclast-mediated alveolar bone resorption as well as apical migration of the junctional epithelium.[2]

Severity and progression of periodontal disease, as well as its response to therapy, are influenced by various factors, including genetics, oral hygiene, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and stress.

The nature and the pathogenesis of periodontal disease can be influenced by a multitude of drugs, especially those that interact with inflammatory and immune responses.[3] The availability of drugs to treat various systemic diseases is increasing, and this calls for investigating the effect of such medications on periodontium in health and disease. A plethora of drugs influencing immune-inflammatory pathways include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, immunosuppressants, bisphosphonates, statins, and corticosteroids. However, many of these agents exhibit unwanted side effects which may surpass their periodontal benefit.[3]

Recently, antidepressant drugs with possible anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities have gained wide acceptance for the treatment of moderate-to-severe depression. Branco-de-Almeida et al. showed that fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), could ameliorate ligature-induced periodontitis in rats.[4] A similar observation was made in a recent human cross-sectional study by Bhatia et al.[5] Venlafaxine, a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), has also been described to possess anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects.[6,7] Desvenlafaxine is an S enantiomer of venlafaxine. Apart from its main antidepressant action, venlafaxine has shown a significant anti-inflammatory effect by reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IF-γ) in various in vitro model and animal studies.[7,8,9] However, there is only one published study available on the effect of venlafaxine on periodontal attachment loss. In this rat study, venlafaxine failed to exert its anti-inflammatory effect on ligature-induced periodontitis model.[10] Thus, the research question was whether desvenlafaxine has an impact on periodontal parameters in patients suffering from depression with chronic periodontitis (CP). In light of the above varied facts, the present preliminary study was conducted with an aim to investigate the possible association between desvenlafaxine intake and clinical periodontal parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sample selection

This single-masked observational study was conducted jointly by the department of periodontics and oral implantology and the department of psychiatry. The study was in accordance with ethical principles enlisted in the Declaration of Helsinki 1964, as revised in 2013, and approved by the institutional review board. The study was started only after obtaining ethical approval from the ethical committee of the institution.

Patients who met the selection criteria were enrolled in the study. Periodontal parameters of the participants were recorded at one time point. No dental procedure was performed on the study participants before recruiting into the study.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) CP patients with psychiatric disorder of moderate depression (diagnosed according to the International Classification of Diseases Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, 10th Revision, Diagnostic Criteria for Research [ICD-10-DCR]),[11] (2) age range of 30–60 years, (3) presence of ≥16 natural teeth other than third molars, and (3) no periodontal treatment ≤6 months prior to the study.

Chronic periodontitis criteria

CP criteria included at least two interproximal sites with attachment loss (AL) ≥4 mm (not on same tooth) or at least two interproximal sites with probing depth (PD) ≥5 mm (not on same tooth).[12]

Diagnosis of depression

Diagnosis of depression was made by an experienced psychiatrist (HK). For diagnosis of moderate depression by ICD-10-DCR criterion, symptoms may consist of the following:

Depressive episode lasting for 2 weeks to a degree that is definitely abnormal for an individual

Loss of interest in normal activities

Increased fatigability coupled with reduced concentration, self-esteem, disturbed sleep, or appetite.

Exclusion criteria

Any history of systemic illness associated with periodontal disease; treatment with antibiotics, steroids, immunosuppressants, and host modulatory drugs within the last 3 months prior to the study; psychiatric disorder other than depression or any other comorbid psychiatric disorder; patients on any other antidepressant apart from drug under investigation; and current or past smokers or those with the use of smokeless tobacco in any form.

Study groups

Of 212 patients referred from the department of psychiatry, 135 participants were included in the study on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Prior written informed consent was taken from each patient before inclusion into the study. The study participants comprised two main groups: test group comprised 63 patients (29 males and 34 females) taking once-daily (OD) dose of 50 mg/day desvenlafaxine (Zyven-OD, Zydus Cadila Healthcare [Neuro], Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India) orally for a minimum of 2 months and the control group participants comprised 72 patients (35 males and 37 females) matched for psychiatric diagnosis, who had not started with any antidepressant medication.

Clinical assessment

The following clinical periodontal parameters were recorded: plaque index (PI),[13] gingival index (GI),[14] sulcus bleeding index (SBI),[15] bleeding on probing (BOP) (in percentage), PD, and AL. A University of North Carolina-15 probe was used for the measurements. Clinical measurements of SBI, BOP, PD, and AL were recorded at six sites (mesiobuccal, mid-buccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, mid-lingual, and distolingual) for each tooth, whereas PI and GI were recorded at four sites per tooth. Bleeding sites were assessed in a dichotomous way, and scores were recorded as percentage of sites positive per participant (BOP percentage).

All the periodontal variables were recorded by a single trained calibrated examiner (AB) who was masked to the group to which patient belongs. In addition, examination by single examiner prevented inter-examiner variability. Examiner reproducibility of clinical measurements was verified by carrying out double clinical periodontal data recording at the same visit for PD and AL on 10% of the sample. Operator calibration for PD and AL was based on >90% and >85% intra-examiner reproducibility within 1 mm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Power estimation for the study was done post hoc, using G power software (G*Power v. 3.0.10, Heinrich-Heine University Du¨sseldorf, Du¨sseldorf, Germany). Fixed-effect size (d) was calculated using the standard difference in AL as output variable. With a set significance level of two-sided α = 0.05, a sample of 135 with allocation ratio of 1:1, and computed d = 0.67, statistical power exceeded 90%. Data normalcy was checked using Shapiro–Wilk test. Data were found to be nonnormally distributed. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard error. Nominal data were represented in percentage. For categorical data, Chi-square test was applied, whereas for continuous data, Mann–Whitney-U test was used to compare patients with and without antidepressant medication. All statistical analyses were two tailed, having a significance level set at 0.05 (SPSS v. 21, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Of the total 212 participants screened for the study, 135 participants met the inclusion criteria. Participants taking desvenlafaxine had been taking them for an average of 5.85 months (2–48 months). Average age of the test group was 37.58 years, and the average age of the control group was 34.25 years.

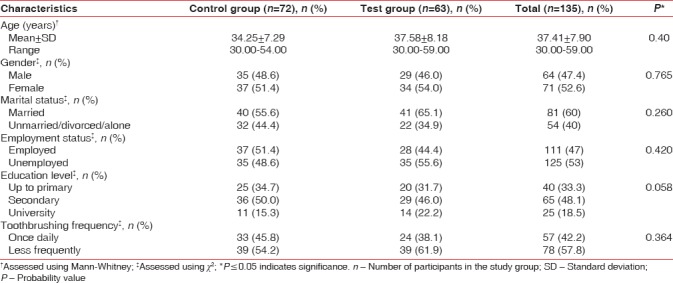

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic data of the study population. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of demographic and behavioral parameters (tooth-brushing frequency).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables of the study groups

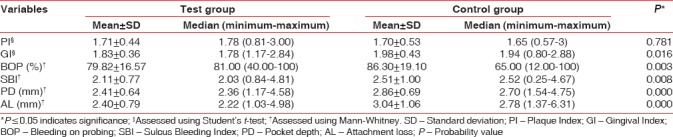

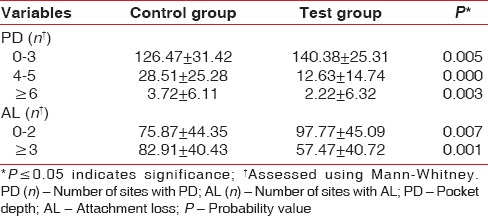

Table 2 demonstrates the comparison of clinical periodontal parameters between the two groups. Mean scores for all the clinical measurements were higher in control group as compared to desvenlafaxine group. In addition, the number of sites with PD = 4–5, PD ≥6, and AL ≥3 was greater in the control group and exhibited significant difference as compared to that of the test group [Table 3].

Table 2.

Comparison of periodontal variables between control group and test group

Table 3.

Comparison of the control and test groups in terms of number of site per patient with varying pocket depth and attachment loss (mean±standard deviation, [%])

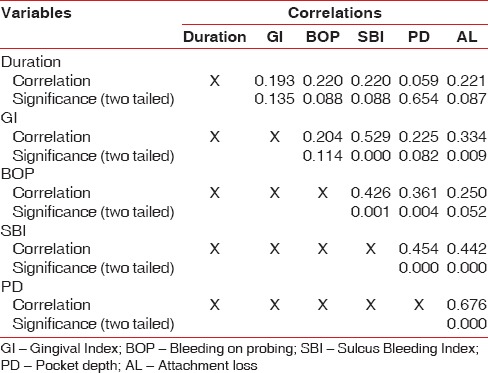

Results of partial correlation analysis to assess the correlation between duration of desvenlafaxine usage and clinical periodontal parameters did not reveal any significant correlation [Table 4].

Table 4.

Correlation of different variables on applying partial correlations analysis after controlling for confounders (Plaque Index, age)

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study observed the association of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor–desvenlafaxine, with clinical inflammatory periodontal parameters in a population suffering from clinical depression. Periodontal parameters of participants taking desvenlafaxine were compared to similar diagnostic matched individuals who were yet to be given treatment for depression.

Test group patients were on a fixed-dose regimen of desvenlafaxine, i.e., 50 mg OD. Recommended dose of 50 mg OD is the starting dose as well as therapeutic dose of desvenlafaxine. Furthermore, it is generally agreed that depressive disorder requires several months or longer of sustained pharmacological therapy.[16] A minimum 8-week treatment with desvenlafaxine has shown clinical efficacy in clinical trials.[17] Thus, the test group comprised only those individuals who were taking 50 mg dose of desvenlafaxine OD for a minimum of 2 months.

Control group participants were enrolled from psychiatric population in order to ensure homogeneity between the two groups and to exclude the confounding effect of depressed state. Periodontal measurements of this group were taken on the day of diagnosis of their clinical depression. There was no prohibition of prescribing antidepressants to control group participants. However, the periodontal measurements of this group were collected before they were put on any antidepressant drug.

Demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups [Table 1]. Gender distribution was well balanced between the groups with greater percentage of females in both groups. Age range selected for the present study was 30–60 years, implying that the findings may be applicable to a larger proportion of subset of population suffering from clinical depression. Other demographic variables showed almost similar frequency of distribution without any statistical significant difference.

As compared to control group, participants taking desvenlafaxine showed lower values of all clinical periodontal parameters except PI. Vollmar et al. in an inflammatory co-culture model observed that venlafaxine leads to reduction in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IFN-γ.[8] Furthermore, venlafaxine has shown to reduce inflammatory injury in animal model of induced ulcerative colitis.[18] In addition, anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of venlafaxine were also noticed by Aricioğlu et al. in rat model of inflammation.[6]

However, a study by Carvalho et al. observed that SNRI venlafaxine when given in low dose (10 mg/kg) had no effect on bone loss in ligature-induced periodontitis model in rats.[10] Surprisingly, a high dose (50 mg/kg) yielded enhanced bone loss. Extrapolation to a clinical situation would call for careful considerations regarding dose relationships and interspecies differences.

In humans, the minimum effective dose of venlafaxine is 1.07 mg/kg body weight and the maximum dose is 5.4 mg/kg body weight (for a 70-kg individual). However, the dose of venlafaxine given in Carvalho et al's. study was a high-end dose (50 mg/kg) and over a longer duration (14 days) and thus accelerated bone loss in their study may be attributed to other still unknown mechanisms of action of extremely high doses of the drug.

Mounting data indicate that inflammation may also play a significant role in neuropsychiatric diseases, including major depressive disorder. Various stressors can induce the activation of inflammatory response via release of cytokines. It has long been assumed that the primary therapeutic mechanism of action of antidepressant drugs involves the modulation of monoaminergic systems. However, there is now a growing consensus that this theory is insufficient to explain the therapeutic effects of various antidepressants.

Antidepressants such as SSRI/SNRIs possess significant anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory properties. The mechanism by which antidepressant drugs alleviate inflammation is still not fully elucidated. However, the anti-inflammatory properties via modulation of serotonergic and/or norepinephrine neurotransmission are merely speculative. Abdel-Salam et al. observed that sertraline, an SSRI, exacerbated carrageenan-induced inflammation.[19] However, fluoxetine, an antidepressant from the same class of drugs, exhibited potent anti-inflammatory effects in a vast number of experimental studies.[4,5,20] A similar observation has been noted in a recent study by Horowitz et al. where venlafaxine exerted anti-inflammatory effects in human hippocampal cells.[21]

Antidepressant drugs differ in their selectivity for actions on increasing serotonin and norepinephrine concentrations. Further research is required to decipher the precise anti-inflammatory potencies of these drugs. In addition, safe and effective drug dosing is necessary, regardless of its purpose of administration.

The number of sites with PD 4–5 mm and PD ≥6 mm was higher in control group as compared to test group participants. Similarly, the number of sites with AL ≥3 was higher in control group participants.

Result of partial correlation analysis in the test group to determine the correlation between periodontal parameters and duration of drug intake did not yield any significant result. Average duration of drug intake in the test group was 5.58 months. Furthermore, a large number (36 out of 63) of the patients in the test group were taking desvenlafaxine for not more than 3–4 months. This might be a short time frame to evaluate the effect of duration of drug intake on periodontal disease parameters.

Some of the strengths of the study were exclusion of smokers from the study, control group being derived from diagnostically matched psychiatric population, and diagnosis of depression by a trained psychiatrist.

Side effect profile of desvenlafaxine includes nausea, dizziness, dry mouth, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and somnolence.[22] Most of these side effects with desvenlafaxine occur in the 1st week of treatment and resolve shortly thereafter.[23] One of the main limitations of the study was its cross-sectional design which cannot yield a definite cause–effect relationship. It can only suspect a drug effect. Longitudinal studies with cohort design are preferable.

CONCLUSION

In the current study, we chose to evaluate the effect of desvenlafaxine only on clinical periodontal parameters. It would be useful for future studies to examine the biomarkers of inflammation to further elucidate the mechanism involved. Finally, further characterization of our findings at different desvenlafaxine dosage is warranted.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkedal-Hansen H. Role of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in tissue destruction. J Periodontal Res. 1993;28:500–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alani A, Seymour R. Systemic medication and the inflammatory cascade. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branco-de-Almeida LS, Franco GC, Castro ML, Dos Santos JG, Anbinder AL, Cortelli SC, et al. Fluoxetine inhibits inflammatory response and bone loss in a rat model of ligature-induced periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2012;83:664–71. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia A, Sharma RK, Tewari S, Khurana H, Narula SC. Effect of fluoxetine on periodontal status in patients with depression: A cross-sectional observational study. J Periodontol. 2015;86:927–35. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aricioğlu F, Buldanlioğlu U, Salanturoğlu G, Ozyalçin NS. Evaluation of antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of venlafaxine in the rat. Agri. 2005;17:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajhashemi V, Minaiyan M, Banafshe HR, Mesdaghinia A, Abed A. The anti-inflammatory effects of venlafaxine in the rat model of carrageenan-induced paw edema. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:654–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vollmar P, Haghikia A, Dermietzel R, Faustmann PM. Venlafaxine exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect in an inflammatory co-culture model. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:111–7. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707007729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubera M, Lin AH, Kenis G, Bosmans E, van Bockstaele D, Maes M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of antidepressants through suppression of the interferon-gamma/interleukin-10 production ratio. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:199–206. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carvalho RS, de Souza CM, Neves JC, Holanda-Pinto SA, Pinto LM, Brito GA, et al. Effect of venlafaxine on bone loss associated with ligature-induced periodontitis in wistar rats. J Negat Results Biomed. 2010;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 08]. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/GRNBOOK.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1449–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blier P, Keller MB, Pollack MH, Thase ME, Zajecka JM, Dunner DL, et al. Preventing recurrent depression: Long-term treatment for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:e06. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebowitz MR, Tourian KA, Hwang E, Mele L Study 3362 Investigators. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study assessing the efficacy and tolerability of desvenlafaxine 10 and 50 mg/day in adult outpatients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minaiyan M, Hajhashemi V, Rabbani M, Fattahian E, Mahzouni P. Effect of venlafaxine on experimental colitis in normal and reserpinised depressed rats. Res Pharm Sci. 2015;10:295–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Salam OM, Nofal SM, El-Shenawy SM. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effects of different antidepressants in the rat. Pharmacol Res. 2003;48:157–65. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacre S, Medghalchi M, Gregory B, Brennan F, Williams R. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent antiinflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:683–93. doi: 10.1002/art.27304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horowitz MA, Wertz J, Zhu D, Cattaneo A, Musaelyan K, Nikkheslat N, et al. Antidepressant compounds can be both pro- and anti-inflammatory in human hippocampal cells. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;18:pii: pyu076. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebowitz MR, Manley AL, Padmanabhan SK, Ganguly R, Tummala R, Tourian KA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/day and 100 mg/day in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1877–90. doi: 10.1185/03007990802161923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebowitz MR, Tourian KA. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of desvenlafaxine 50 mg/d for the treatment of major depressive disorder: A systematic review of clinical trials. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12:pii: PCC09r00845. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09r00845blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]