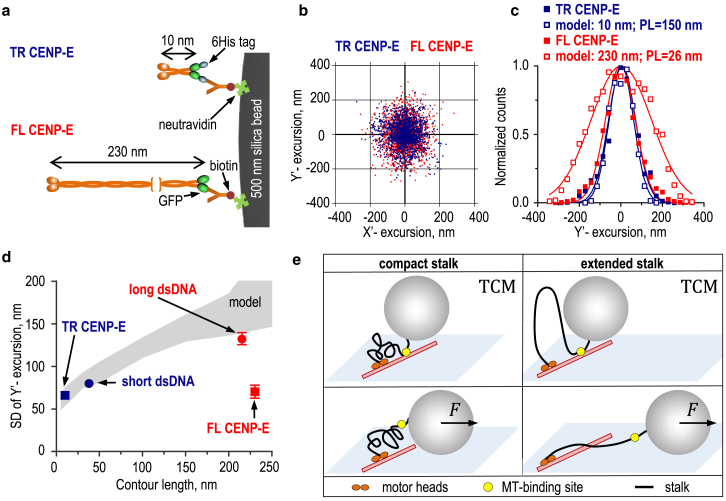

Figure 4.

Analysis of bead excursions for wild-type (full-length (FL)) and truncated (TR) CENP-E kinesins. (a) A strategy is shown for conjugating CENP-E kinesins to microbead cargo. (b) Cloud plots show microbeads carried by different CENP-E kinesin constructs, based on 26 beads for TR CENP-E and 18 for FL CENP-E. For each tether, 2000 randomly selected coordinates are shown. (c) Histograms show distributions of experimentally measured (solid symbols) versus predicted MT-perpendicular (Y’) bead excursions (open symbols). CENP-E tethers were modeled with specified contour lengths and persistence lengths. Each distribution (based on 2000 coordinates) was fitted to a Gaussian function and normalized to its mean value. (d) SDs of bead Y’-excursions are shown versus the contour length of the molecular tether. Squares show experimental measurements for TR and FL CENP-E, and circles show experimental measurements for kinesin-1 with different dsDNA links. The gray area represents the theoretical prediction from Fig. 1e for the range of PL = 26–150 nm, with 95% confidence. (e) Possible models show the FL CENP-E configuration to explain the low SD of the Brownian bead excursions. Upper cartoons show that if the MT-binding site (yellow) within the CENP-E tail is persistently attached to MT, in the TCM assay both compact and extended stalk configurations should lead to similarly small bead excursions limited only by the bead-proximal segment of the unstructured CENP-E tail. In lower cartoons, external sideways force prevents the tail’s MT-binding and stretches CENP-E, limited by the compactness of the stalk (left). In the “extended” stalk model (right), the force-dependent bead displacement should increase up to the total contour length of CENP-E. To see this figure in color, go online.