Abstract

Purpose

Expanded carrier screening (ECS) is an available component of preconception and prenatal care. There is complexity around offering, administering, and following-up test results. The goal of this study is to evaluate current physicians’ utilization and attitudes towards ECS in current practice.

Methods

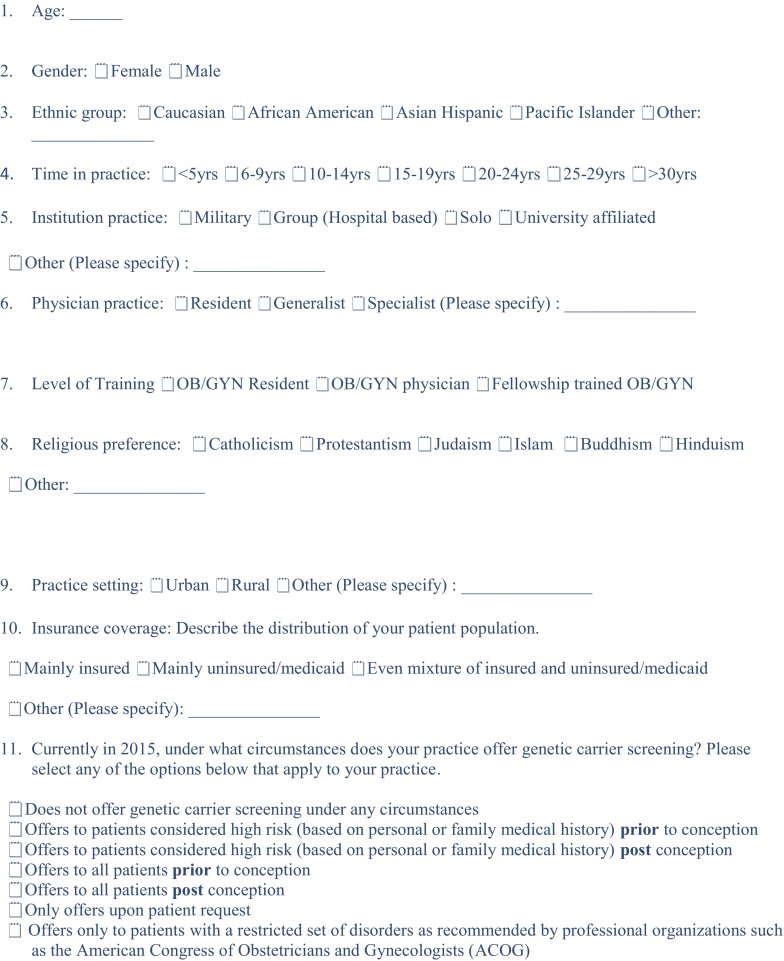

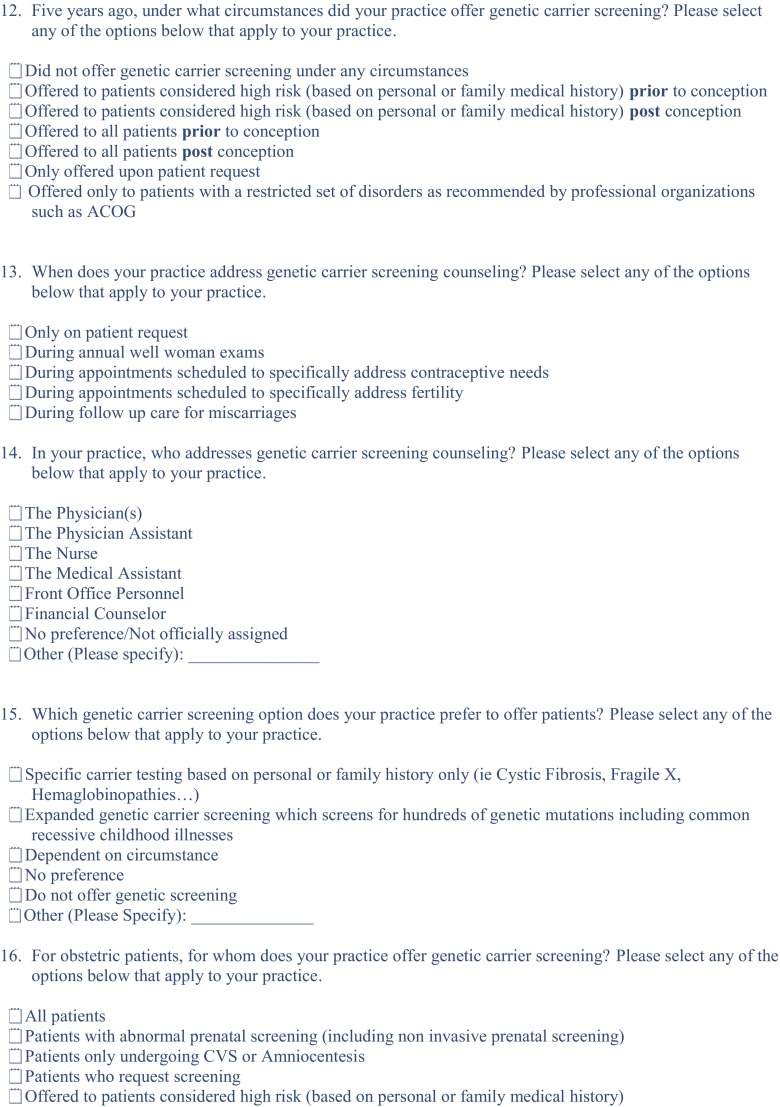

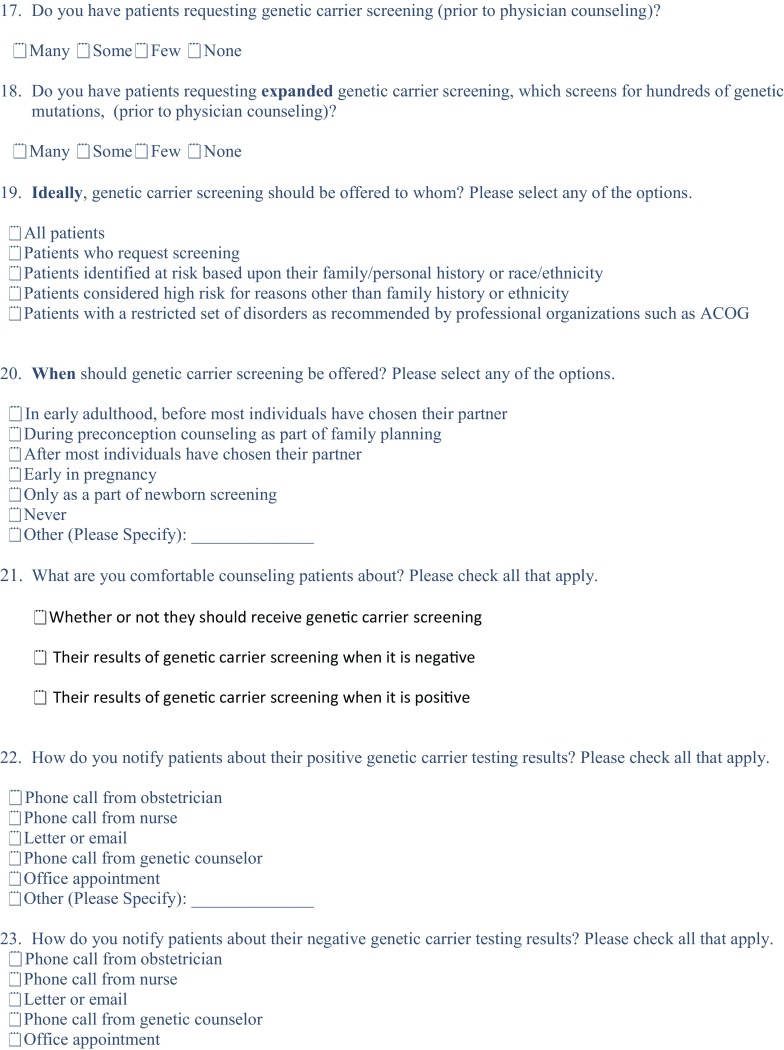

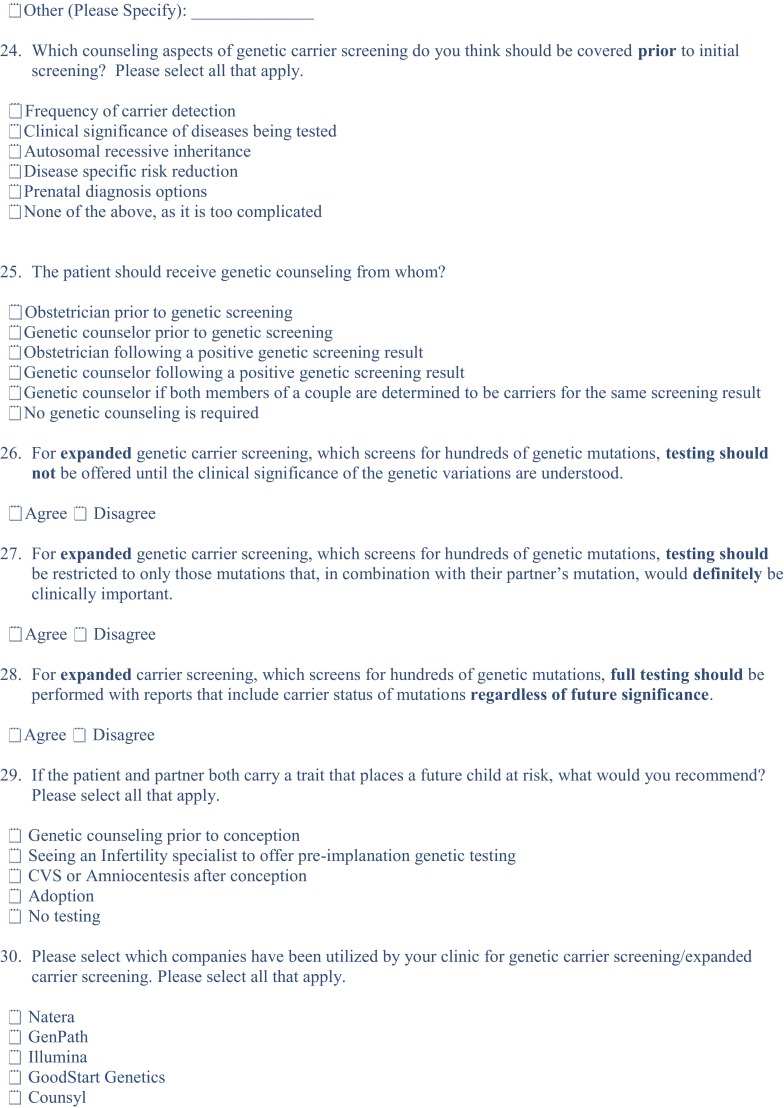

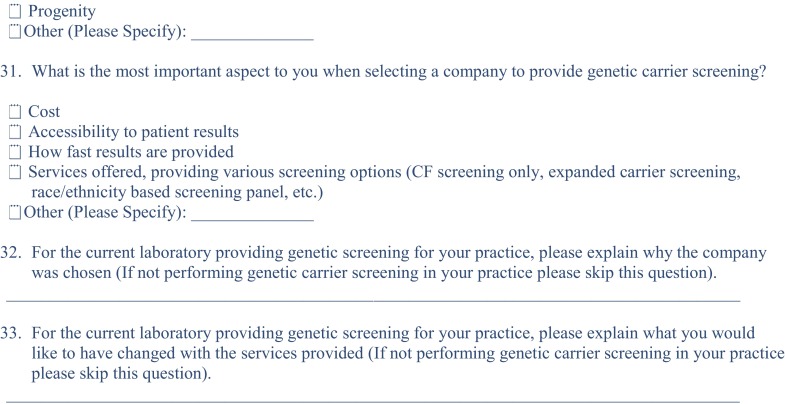

This was a prospective qualitative survey study. A 32-question electronic survey was distributed during a 1-year period to obstetricians-gynecologists who were identified using a Qualtrics listserv database.

Results

While more than 90% of physicians offered ethnic-based carrier screening (CS), ECS was offered significantly less (2010, 20.6%, and 2016, 27.1%). Physicians who were not fellowship-trained in reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI) preferred ethnic-based carrier screening (95.9 vs 16.8%; P < 0.001). REI subspecialists were more likely to offer ECS (80%) compared to 70% of maternal fetal medicine physicians (MFM). Physicians were comfortable discussing negative results (53.6%) compared to positive results (48.4%). Most physicians (56%) believed that ECS should not be offered until the significance of each disease is understood; 52% believed that testing should be restricted to those conditions important to couples; while 26% felt that testing should be done regardless of the clinical significance.

Conclusions

Discussion and application of ECS has increased in clinical practice. However, lack of comfort with counseling and varying beliefs surrounding ECS continue to hinder its utilization. Further education and training programs, and subsequent evaluation are warranted.

Keywords: Carrier screening, Expanded carrier screening, Genetic screening, Genetic counseling, Reproductive genetics

Introduction

In the 1970s, carrier screening (CS) programs were introduced in ethnic communities with a high prevalence of severe recessive disorders, including Tay-Sachs disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish community, beta-thalassemia in couples from the Mediterranean regions, and cystic fibrosis in Ashkenazi Jews and Northern European Caucasians [1–3].

Until recently, professional organizations recommended a condition-specific screening approach for providers to offer carrier screening for individual conditions based on carrier frequency in sub-populations (race and ethnic-based), condition severity, and detection rates. Technical limitations and cost were important considerations that limited screening to single gene disorders [4]. Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends ethnic-based CS for all couples considering conception [5]. However, ethnic-based CS is difficult due to greater population mobility leading to fewer closed societies, inter-racial reproduction, global acceptance of adoption, and changes in adoption practices. These result in difficulties for patients to self-describe their race and ethnicity.

Recent high-throughput next-generation sequencing has allowed ECS at costs that are seemingly acceptable to many couples [6–10]. However, studies show that most obstetrician-gynecologists (OBGYNs) do not consider genetic CS to be an important part of their daily practice. In many cases, providers do not offer patients CS at all and this has been attributed to lack of confidence and knowledge of the area of genetics [11]. As genetic technologies evolve and are encouraged to be incorporated into clinical practice, utilization and attitudes of physicians are increasingly important. At present, there are limited data describing provider attitudes around the implementation of ECS. We surveyed OBGYNs to assess current practice utilization and attitudes regarding the implementation of ECS into clinical practice.

Materials and methods

A prospective qualitative survey study was reviewed and approved by the University Institutional Review Board. From July 2015 to August 2016, an electronic and paper version of a 32-question survey was distributed to generalist OBGYNs, fellowship-trained specialists (MFM and REI), and OBGYN residents and fellows in training. Survey subjects were identified using a Qualtrics listserv database. Confidentiality was protected with the use of a unique identification (ID) number that was used on all data collection forms and when performing statistical analyses.

The survey consisted of domains to assess physician attitudes regarding medical and ethical aspects of ethnic-based CS and ECS in 2010 and in current practice. The survey addressed physicians’ practices 5 years prior, which accounted for practice in 2010. Questionnaires with closed-ended questions were analyzed. The survey is attached in Appendix A.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed for all items. Respondents were grouped for analysis using gender and years in practice (<5 years, 5 to 9 years, and ≥ 10 years). Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages with differences assessed by chi-square values. Significance was assessed at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Two hundred ninety-seven physicians responded to the survey. Distributions were based on the number who responded. Gender broke down as follows: 29% (84) male and 71% (206) female. The average age was 38 years with a range of 23 to 76 years. Eighty-four percent (245) were Caucasian, 7% (20) were Asian, 4% (13) were African-American, 2% (5) were Hispanic, and 3% (8) self-reported as Other. Current level of training included 55% (n = 160) Residents, 4% (n = 11), Fellows, 24% (n = 71), Generalist OBGYNs, and 17% (n = 49) fellowship-trained Subspecialists. The number of years in practice ranged from less than 5 years, 54.2% (n = 158); 5–9 years, 8.0% (n = 26); and ≥ 10 years 36.8% (n = 107) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the survey respondents

| Frequencies (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female Male |

206 (71%) 84 (29%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian Asian African-American Hispanic Other |

245 (85%) 20 (7%) 13 (4%) 5 (2%) 8 (3%) |

| Religious preference | |

| No religious preference Protestantism Catholicism Judaism Hinduism Islam Buddhism |

94 (31.6%) 84 (28.3%) 74 (24.9%) 23 (7.7%) 4 (1.3%) 4 (1.3%) 1 (0.3%) |

| Level of training | |

| Residents Fellows Generalists Subspecialists |

160 (55%) 11 (4%) 71 (24%) 49 (27%) |

| Years in practice | |

| < 5 years 5–9 years ≥ 10 years |

158 (54.2%) 26 (8%) 107 (36.8%) |

Comparison of ethnic-based CS and ECS offered between 2010 and 2016

A significant increase in those offering exclusively ECS occurred between 2010 and 2016 (20.6 vs 27.1%, P < 0.01). However, the overwhelming majority of physicians continue to offer ethnic-based CS only and/or combination of both, based on history (2010, 98.3% and 2016, 98.8%). Subspecialists were and continue to be more likely to offer ECS than all other physicians surveyed (2010, 36.7%; 2016, 57.1%; P < 0.001).

Overall, no differences were noted whether ECS was offered pre- or post- conception for all physicians excluding residents in 2010 (20.6 and 24.1%) and 2016 (19.8 and 27.1%). However, Generalists and Subspecialists were more likely to offer preconception ECS (9.9 vs 25.4%, P < 0.05 and 6.7 vs 57.1%, P < 0.05) and post-conception (21.1 vs 39.4%, P < 0.05 and 22.4 vs 34.6%, P > 0.05) in 2016 than they were in 2010.

Preferences for ethnic-based CS or ECS in 2016

Overall, physicians preferred ethnic-based CS to ECS (95.9 vs 16.8%, P < 0.001). Significantly more generalists preferred ethnic-based CS (66%, P < 0.001) compared to Residents (43.1%), Fellows (18.2%), and Subspecialists (40.8%). Subspecialists equally preferred ethnic-based CS and ECS (40.8 and 42.8%). However, more Subspecialists preferred ECS than Residents (10%), Fellows (17.3%), and Generalists (12.6%, P < 0.001). REI Subspecialists were also most likely of all Subspecialists to offer ECS (80%).

Practical issues regarding ethnic-based CS and ECS in the clinical setting in 2016

Physicians in training (Residents (54.3%), Fellows (54.5%)) are less likely to address genetic screening in the office than Generalist (88.7%) and Subspecialists (87.7%, P < 0.01). Nurses from Subspecialists’ offices were also more likely to address ethnic-based CS/ECS (42.9%, P < 0.001) compared to other nurses from other practice settings (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Who addresses ethnic-based CS/ECS in a clinical setting in 2016

| Total (291) | Resident (160) | Fellow (11) | Generalist (71) | Subspecialist (49) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician | 68.3% (199) | 54.3% (87 | 54.5% (6) | 88.7% (63) | 87.7% (43) | < 0.001 |

| PA | 11.1% (22) | 5% (8) | 9% (1) | 11.2% (8) | 10.4% (5) | NS |

| Nurse | 16.8% (49) | 10.6% (17) | 18.2% (2) | 12.7% (9) | 42.9% (21) | < 0.001 |

| Medical assistant | 4.1% (12) | 1.8% (3) | 0% (0) | 12.7% (9) | 6.1% (3) | 0.013 |

| Front office | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | NS |

| Financial counselor | 0.7% (2) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1.4% (1) | 2% (1) | NS |

NS not significant

Notification of either negative or positive results occurred more frequently with an office appointment (32.2 and 44.3%, P < 0.05) compared to either phone call from a physician (23 and 29.6%), nurse (28.8 and 9.6%), genetic counselor (15.4 and 25.4%) or a letter-email (14.4 and 2.7%). Genetic counselors were used to discuss negative results (15.4%) and significantly more for positive results (25.4%, P < 0.05; see Table 3). Overall, more physicians were comfortable discussing negative results (53.6%) compared to positive results (48.4%), though only 196 responded to the question about encountering positive ethnic-based CS/ECS results. All Residents (25 vs 40.6%, P < 0.05), Generalists (36.3 vs 45.5%, P < 0.05), and Subspecialists (53.1 vs 79.5%, P < 0.05) were significantly less comfortable discussing positive compared to negative results (see Table 4).

Table 3.

How patients notified of negative and positive ethnic-based CS/ECS Results

| Phone call by physician | Phone call by nurse | Letter-email | Phone call by genetic counselor | Office appointment in person | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative results | ||||||

| Total (291) | 23% (67)* | 28.8% (84)^ | 14.4% (42)^ | 15.4% (45)^ | 32.2% (94)^ | 1.4% (4) |

| Resident (160) | 23.1% (37) | 15.6% (25) | 16.9% (27) | 13.1% (21) | 25% (40) | 1.3% (2) |

| Fellow (11) | 18.2% (2) | 18.2% (2) | 0% (0) | 18.2% (2) | 18.2% (2) | 0% (0) |

| Generalist (71) | 28.2% (20) | 47.9% (34) | 12.7% (9) | 29.6% (21) | 56.3% (40) | 2.8% (2) |

| Subspecialist (49) | 16.3% (8) | 46.9% (23) | 12.2% (6) | 18.4% (9) | 40.8% (20) | 0% (0) |

| P value | 0.49 | < 0.001 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.008 | 0.58 |

| Positive results | ||||||

| Total (291) | 29.6% (86)* | 9.6% (28)^ | 2.7% (8)^ | 25.4% (74)^ | 44.3% (129)^ | 1.4% (4) |

| Resident (160) | 25% (40) | 5% (8) | 4.4% (7) | 20.6% (33) | 36.9% (59) | 2.5% (4) |

| Fellow (11) | 9.1% (1) | 9.1% (1) | 0% (0) | 27.3% (3) | 36.4% (4) | 0% (0) |

| Generalist (71) | 39.4% (28) | 11.3% (8) | 0% (0) | 23.9% (17) | 60.6% (43) | 0% (0) |

| Subspecialist (49) | 34.7% (17) | 22.4% (11) | 2% (1) | 22.4% (21) | 46.9% (23) | 0% (0) |

| P value | 0.05 | 0.004 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.009 | 0.35 |

*P = 0.07, ^P < 0.05

Table 4.

Provider comfort discussing negative and positive ethnic-based CS/ECS results

| Total | Resident | Fellow | Generalist | Subspecialist | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfortable discussing negative results | 53.6% (156/291) | 40.6% (65/160) | 45.5% (5/11) | 66.2% (47/71) | 79.5% (39/49) | < 0.001 |

| Comfortable discussing positive results | 48.4% (95/196) | 25% (32/128) | 36.3% (4/11) | 46.5% (33/71) | 53.1% (26/49) | < 0.001 |

Personal feelings surrounding ECS in the clinical setting

Overall, 56% of physicians believed that ECS should not be offered until the significance of each disease is understood, 52% believed that testing should be restricted to those important to couples, while 26% of physicians felt that testing should be done regardless of the clinical significance. These findings were more apparent in Generalists (83%) compared to Residents (41%), Fellows (54%), and Subspecialists (65%) (P < 0.05).

Approximately two thirds of physicians felt that couples should have counseling if both were carriers of the same disease, 38% felt that couples would refer to an infertility specialist for pre-implantation diagnosis discussion, 31% would suggest a CVS or amniocentesis, post-conception, while 15% thought a couple should consider adoption. Residents were less likely to direct patients to counseling (50%), refer to an infertility specialist (28%), and suggest a CVS or amniocentesis (26%) (P < 0.05). More than one in four subspecialists (26.5%) thought that adoption should be considered (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Physicians personal attitudes if both partners carry the same mutation

| Total (291) | Resident (160) | Fellow (11) | Generalist (71) | Subspecialist (49) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counseling prior to conception | 62.2% (186) | 50% (80) | 63.6% (7) | 85.9% (61) | 77.6% (38) | < 0.001 |

| Refer to infertility specialist | 37.8% (110) | 28.1% (45) | 45.5% (5) | 43.7% (31) | 59.2% (29) | 0.001 |

| CVS-amniocentesis | 31.3% (91) | 25.6% (41) | 36.4% (4) | 42.3% (30) | 32.7% (16) | 0.09 |

| Adoption | 15.5% (45) | 6.9% (18) | 18.2% (2) | 16.9% (12) | 26.5% (13) | 0.07 |

Gender and years in practice when considering ethnic-based CS/ECS

No differences with respect to gender or years in practice were noted for those who preferred any type of genetic carrier screening. However, males preferred ECS compared to females (27% vs 13%, P < 0.01), while providers with < 5 years of experience (9.5%) were less likely to offer ECS compared to those between 5 to 9 years (23%) and ≥ 10 years of experience (26%, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Carrier testing is aimed at identifying couples at risk of having a child affected by severe heritable conditions. Identification of carriers allows couples to choose fetal testing and then to make informed reproductive choices. The screening paradigm has evolved with high-throughput technology to facilitate screening an expanded number of conditions and variants. Professional organizations including American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine now acknowledge the availability of ECS [12].

Our data suggest that in the last 6 years, most providers still preferred and offered ethnic-based CS to patients, while ECS remained underutilized (except for REI Subspecialists) with approximately one in four providers offering this screening. More than half of providers also felt that ECS should not be offered until the clinical significance of each disease is fully understood. In general, physicians were comfortable discussing negative results compared to positive results. Males and providers with more experience were also more likely to offer ECS.

Previous studies suggest there have been multiple practical challenges with the implementation of ethnic-based CS into routine clinical care. This includes an ACOG survey from 2000 where 24% of ACOG fellows (n = 564) did not routinely review family histories at GYN visits, 39% rated genetic diseases as last among priorities in the office, and 66% felt undereducated about counseling. In this study, only 20% provided genetic counseling to their patients [11]. Morgan et al. also reported that almost one half of physicians did not ask non-pregnant patients whether a family member was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. In that study, physicians had concerns related to knowledge of CF and the ability to interpret a positive screening test as reasons for not incorporating cystic fibrosis screening into clinical practice. Moreover, physicians expressed the need to minimize the complexity of clinical guidelines for population-based genetic screening and continuing education [13].

Other issues and concerns that have been reported include time constraints and the need for more educational support and materials [14]. Benn et al. reported that only one-third of providers were comfortable with pre-test counseling and less than 25% were comfortable reviewing results [15]. The main concerns reported included the time needed for counseling and coordinating follow-up studies as well as comfort with counseling after a positive result. Interestingly, the knowledge deficit that physicians report is inconsistent with at least one study on physicians’ knowledge around ethnic-based CS. Ready et al. reported in ASRM and ACOG survey-based questionnaire that physicians felt they had adequate knowledge about carrier screening in general [16]. Together, these studies suggest that physicians may have the knowledge base but do not feel comfortable providing counseling (83%) and/or a consultation (78%) would be essential [16].

Thus, the major barriers that exist for routine implementation of ethnic-based CS appear to exist for ECS. Our results show discrepancies with knowledge and comfort as more than 50% were comfortable with ECS counseling, and slightly less than one half were comfortable with discussing positive results. Moreover, a genetic counselor was only offered to 15% of patients after a negative result and 25% after a positive result. Another barrier may be that physicians believe that testing should only be offered for clinically relevant disease testing which is like the findings Benn et al. [15].

Our finding that males were more likely than females to offer ECS is consistent with other medical literature regarding gender differences and medical decisions [17–19]. These appear to be real and their impact regarding ECS needs to be further explored. Whether ECS panels should be offered without known clinical significance is a challenging topic. Previous literature by De Wert et al. has eloquently discussed that the moral compass is directed by whether the goal is prevention of genetic diseases in society (beneficence and non-maleficence) versus patient autonomy to make reproductive choices [20]. The impact of the knowledge as carriers of an unknown genetic finding also has been the potential for creating a stigma for those who are positive carriers as has been reported in preconception Tay-Sachs screening programs in the orthodox Jewish community [21]. Technology in general creates ethical dilemmas as guidelines for utilization lag behind the ability for enhanced throughput [22]. ECS is another example of advancing technology which has accelerated faster than ethical considerations can be explored, and guidelines will continue to evolve regarding utilization of ECS [22].

The strengths of our study include that all surveys were anonymous, increasing likelihood of truthful responses. Furthermore, the survey was distributed nationally, giving a wide geographic distribution of thoughts and beliefs to closely represent that of the current practicing OBGYN physician body. Distribution across multiple levels of experience also allowed for sub-analysis of different practices among specialists and years of practice. The potential weakness of our study is that this survey has not previously been validated. There are types of errors in survey-based research which includes coverage, sampling, nonresponse, and measurement. Additional limitations of our study are that most physicians practice in an urban setting, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings to nonurban settings. Approximately half of the respondents were in residency training where some of the viewpoints may reflect their program rather than individual beliefs and practices. The time required for reviewing ECS results and the cost of ECS was also not investigated primarily due to study design. The survey design allowed for incomplete answers and percentages reported included non-responders. Given that the survey was electronically distributed, clarifying responses to physician answers could not be obtained. Additionally, as the survey only captured physicians’ opinions and attitudes at one given point in time, tracking future trends would be time-consuming and costly.

In conclusion, our study has shown that ECS has increased in clinical practice over the past 6 years, yet the number of physicians offering ECS remains significantly less than ethnic-based CS. ACOG committee opinion March 2017 desires an increased role in genetic screening and states that ECS is an acceptable method for evaluation [5]. Further, there is a lack of recommendation of who is the best counselor. If physicians are going to be the primary counselors, further education is needed to prepare them for this role to improve comfort and competence. However, what this training entails and when it occurs is topic of further investigation. Lastly, further education and training programs are needed to recommend when ECS should be offered in clinical practice as a disconnect exists between when physicians believe ECS should be offered and what is occurring in clinical practice. Overall, while utilization of ethnic-based CS and ECS has increased over the past 6 years, it is still far from standard of care.

Acknowledgments

L. Ashley Duckworth, Wright State University, no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Funding information

Steven R. Lindheim, MD, MMM received a grant from Progenity®, San Diego, CA. Study funded by Progenity®, unrestricted research grant.

Conflict of interest

There was no involvement by Progenity in writing this manuscript. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Military disclaimer

The statements made in this article are not a reflection of the United States Government or Military positions or opinions.

References

- 1.Simpson JL. Choosing the best prenatal screening protocol. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2068–2070. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaback MM. Population-based genetic screening for reproductive counseling: the Tay-Sachs disease model. Eur J Pediatr;159 Suppl 3:S192–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cousens NE, Gaff CL, Metcalfe SA, Delatycki MB. Carrier screening for beta-thalassaemia: a review of international practice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(10):1077–1083. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajaj K, Gross SJ. Carrier screening: past, present, and future. J Clin Med. 2014;3(3):1033–1042. doi: 10.3390/jcm3031033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee Opinion No. 691 Summary: carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):597–599. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell CJ, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Hateley SL, Ganusova EE, Mudge J, et al. Carrier testing for severe childhood recessive diseases by next-generation sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(65):65ra4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kingsmore S. Comprehensive carrier screening and molecular diagnostic testing for recessive childhood diseases. PLoS Curr. 2012;02:e4f9877ab8ffa9. doi: 10.1371/4f9877ab8ffa9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner AK, Valencia CA, Rhodenizer D, Espirages M, Da Silva C, Borsuk L, et al. Development and performance of a comprehensive targeted sequencing assay for pan-ethnic screening of carrier status. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16(3):350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssens S, Chokoshvili D, Vears D, De Paepe A, Borry P. Attitudes of European geneticists regarding expanded carrier screening. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau TK. Obstetricians should get ready for expanded carrier screening. BJOG. 2016;123(Suppl 3):36–38. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins-Haug L, Erickson K, Hill L, Power M, Holzman GB, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ opinions and attitudes on the role of genetics in women's health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(8):873–879. doi: 10.1089/152460900750020900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards JG, Feldman G, Goldberg J, Gregg AR, Norton ME, Rose NC, Schneider A, Stoll K, Wapner R, Watson MS. Expanded carrier screening in reproductive medicine-points to consider: a joint statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, National Society of Genetic Counselors, Perinatal Quality Foundation, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):653–662. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan MA, Driscoll DA, Mennuti MT, Schulkin J. Practice patterns of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding preconception and prenatal screening for cystic fibrosis. Genet Med. 2004;6(5):450–455. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000139509.04177.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssens S, De Paepe A, Borry P. Attitudes of health care professionals toward carrier screening for cystic fibrosis. A review of the literature. J Community Genet. 2014;5(1):13–29. doi: 10.1007/s12687-012-0131-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benn P, Chapman AR, Erickson K, Defrancesco MS, Wilkins-Haug L, Egan JF, et al. Obstetricians and gynecologists’ practice and opinions of expanded carrier testing and noninvasive prenatal testing. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(2):145–152. doi: 10.1002/pd.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ready K, Haque IS, Srinivasan BS, Marshall JR. Knowledge and attitudes regarding expanded genetic carrier screening among women’s healthcare providers. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(2):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks DJ. Differences in patient screening mammography rates associated with internist gender and level of training and change following the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Guidelines. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(6):749–753. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delgado A, Saletti-Cuesta L, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Gil-Garrido N, Luna Del Castillo Jde D. Gender inequalities in COPD decision-making in primary care. Respir Med. 2016;114:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206–213. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Wert GM, Dondorp WJ, Knoppers BM. Preconception care and genetic risk: ethical issues. J Community Genet. 2012;3(3):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raz AE, Vizner Y. Carrier matching and collective socialization in community genetics: Dor Yeshorim and the reinforcement of stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(9):1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall KP. Has technology introduced new ethical problems? J Bus Ethics. 1999;19(1):81–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1006154023743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]