Abstract

Minimally invasive surgery is commonly used for hysterectomies because of its many benefits over open surgery. Although small uteri can be removed whole in this approach, larger specimens must be morcellated. Power morcellation has come under scrutiny recently because of concerns that it can disseminate occult uterine sarcoma, other undiagnosed malignancies, and benign tissue. To limit uterine tissue dissemination, morcellation can be contained within a bag. In addition, a careful preoperative workup should be performed to minimize the risk of occult malignancy. New techniques that allow surgeons to offer more women a minimally invasive approach should be investigated and encouraged.

Introduction and Background

Minimally invasive gynecologic surgery has many benefits over open surgery, including lower blood loss, decreased pain, shorter hospital stay, faster recovery, and fewer wound, bowel, and thrombotic complications.1–4 In addition, laparoscopic hysterectomies have a three-fold lower risk of mortality than open hysterectomies.4 In a total laparoscopic hysterectomy, a small uterus can be removed whole through the vagina at the end of the procedure. If the uterus is large, or in cases of supracervical hysterectomy (the cervix is not removed) or myomectomy (when no colpotomy is available through which to extract the specimen), the tissue must be morcellated before extraction. Morcellation can be performed manually with a scalpel, either vaginally or through a mini-laparotomy incision, or laparoscopically with a power morcellator.5

The Problem

Power morcellation has come under scrutiny recently because of concerns regarding the dissemination of uterine tissue, particularly uterine sarcoma, throughout the abdomen. This concern was brought to public attention after a high-profile case in which an occult sarcoma was morcellated during a supracervical robotic hysterectomy for suspected benign fibroids at a Harvard-affiliated hospital in Boston. Coverage in the main-stream media was extensive, and in 2014 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning discouraging the use of power morcellation during hysterectomy and myomectomy.6 In addition to concerns about disseminating sarcoma, other risks include dissemination of other malignancies, dissemination of benign tissue, direct damage to surrounding organs, and disruption of the pathologic specimen.7–15

Sarcoma

Uterine sarcomas, including stromal sarcoma and leiomyosarcoma, are of particular concern because they can mimic benign fibroids and are difficult to diagnose preoperatively (see Figure 1). Fibroids cannot be biopsied directly due to concerns about bleeding and sampling error. Additionally, endometrial biopsy will only detect sarcoma 30–60% of the time (presumably when the sarcoma is eroding into the endometrium), so a negative biopsy does not rule out sarcoma.16–17 One study showed that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in combination with serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme-3 predicted sarcoma18, but that has not been replicated in other centers.

Figure 1.

Uterine sarcomas are of particular concern because they can mimic benign fibroids and are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. The MRI image on the left is a fibroid. The image on the right is a sarcoma. Arrow on the right points to the uterus. Arrowhead on the right points to the sarcoma.

It is worth considering whether the benefits of minimally invasive surgery outweigh the risks of occult sarcoma. Previously, the risk of sarcoma was thought to be 1–2 per 1,000 patients.19–24 However, the 2014 FDA analysis quoted a risk of 1 per 352.6 Although this sounds like a much higher risk, all of these estimates fall within the same 95% confidence interval, and all equal a risk of less than 0.3%. Additionally, the FDA may have reported a higher rate for several reasons. First, the data were derived from nine single-institution studies from academic referral centers, which have higher rates of malignancy than in the community.25–33 Second, the studies analyzed were from five countries, spanning several decades, with varying histopathologic criteria. Third, the studies included postmenopausal women and did not stratify for age. Fourth, no information about how many sarcomas were morcellated was included. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the studies included women with sarcomas that were diagnosed preoperatively. Therefore, a reproductive-age woman presenting for a minimally invasive procedure with a negative preoperative workup may have a much lower rate of occult sarcoma than in the studies analyzed by the FDA.

Risk factors for sarcoma include age greater than 65 years, black race, tamoxifen use for more than five years, pelvic radiation, and a history of Lynch syndrome, hereditary leiomyomatosis, renal cell cancer, or childhood retinoblastoma.34–41 Although a rapidly enlarging myoma is often cited as a risk factor for sarcoma, the evidence suggests this is not a reliable predictor.42–43 For example, in one series of 1300 women undergoing surgery for presumed uterine myoma, the risk of sarcoma was 0.23% overall and 0.27% in those reporting rapid growth, a non-significant difference.42

The largest histologic subgroup of sarcoma is leiomyosarcoma. The overall survival is universally poor, and only 40% of patients are alive at five years.34–35 Recurrence rates and survival outcomes are poor even in the setting of early stage disease. In a recent multiinstitution study of women with stage I–II disease whose uteri were removed intact, 72% experienced a recurrence in the first 2.5 years after diagnosis, and median overall survival was only 52 months for the entire cohort.44 However, there is evidence that morcellation of the sarcoma worsens the prognosis. Although the studies were all small, single-center, and retrospective, they reported that patients who underwent intraperitoneal morcellation of unsuspected leiomyosarcoma had a higher risk of recurrence and shorter progression-free survival than those who underwent en bloc resection. 44, 25, 45 The most recent of these studies demonstrated that those who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy plus uncontained power morcellation had a higher risk of recurrence than those who underwent total abdominal hysterectomy (11 months vs. 40 months recurrence-free survival).45

Other Malignancies

Although most of the debate about uterine morcellation has centered around uterine sarcoma, cervical and endometrial cancers are more common. Because cervical and endometrial biopsies can reliably detect these malignancies preoperatively, the risk of occult dissemination should be low. However, after the 2014 FDA warning, Wright et al. published a new analysis in The Journal of the American Medical Association suggesting that dissemination of cervical and endometrial cancers is not as rare as previously thought. 46 The study used a large prospective database, accounting for 15% of all United States hospital admissions, to analyze the risk of occult malignancy in women undergoing morcellation at the time of their minimally invasive hysterectomy. In a cohort of 200,000 women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy, 15% underwent power morcellation. Of those, 1 in 368 had uterine cancer including all sarcoma and endometrial cancer. Because endometrial cancer is much more common than sarcoma, these data suggest that the FDA estimate of 1 in 352 for sarcoma alone is an overestimate. Additionally, the authors reported that 1 in 1,429 of those who underwent morcellation had some other gynecologic malignancy (cervical or adnexal), and 1 in 99 had endometrial hyperplasia. These findings highlight the importance of appropriate preoperative screening and workup, as most cervical and endometrial cancers should be detected preoperatively.

Another important component of this study was a subgroup analysis revealing that the rate of occult malignancy was highly variable by age. The rate ranged from 1 in 1,572 for women less than 40-years-old, to 1 in 33 for women greater than 65-years-old. However, 80% of women undergoing minimally invasive hysterectomy with morcellation in this cohort were under the age of 50. Therefore, average risk calculations, such as the 1 in 352 rate reported by the FDA, overestimate the risk of occult malignancy for the vast majority of these patients. Given these findings, age specific counseling regarding the rate of occult malignancy would be more appropriate.

Additional Concerns

Other concerns of power morcellation include dissemination of benign tissues, disruption of the pathologic specimen, and direct damage to surrounding organs. 7–15 Dissemination of benign tissue has led to disseminated leiomyomatosis and iatrogenic endometriosis, which can result in pain or bowel obstruction and require reoperation.8–14 Disruption of the pathologic specimen has made it difficult for pathologists to identify malignancy or depth of invasion.7,15 Finally, injury from the rapidly rotating blade of the power morcellator has caused bowel and vascular injuries and has resulted in deaths; surgeon inexperience is cited as the key risk factor for direct injury. Although the focus of this debate has been on power morcellation, manual morcellation can also disseminate tissue and worsen prognosis in the setting of occult malignancy.44

Potential Solutions

As suggested by Wright et al. dissemination of many malignancies could be prevented with an appropriate preoperative workup. The workup should include a history and physical, up-to-date cervical screening, and an endometrial biopsy if indicated. In taking a complete history, special attention should be paid to description of bleeding patterns, menopausal status, and a personal or family history of cancer. A complete physical exam should include an accurate description of uterine size, which is measured according to the size the uterus would reach at different gestational weeks during pregnancy. Special note should be made of prominent lower uterine segment or cervical myomas, as these may increase the chance that morcellation will be required. Cervical cytology screening should be up-to-date, and abnormalities evaluated via the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology guidelines before scheduling surgery.47 Endometrial sampling should be performed per the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology guidelines, which include sampling for women with any abnormal bleeding if they are over 45-years-old or have other risk factors.48,49 Although endometrial biopsy detects an endometrial malignancy up to 95% of the time, sarcoma is only detected 30–60% of the time, so a negative biopsy does not rule out sarcoma.16,17,19 However, endometrial biopsy is still the best test to diagnose sarcoma preoperatively, so if morcellation is planned, a low threshold to biopsy should be used. Imaging such as ultrasound or MRI may be indicated for other reasons (assessing uterine size, mapping fibroid location, etc.) but has not been shown to be useful in diagnosing sarcoma preoperatively.

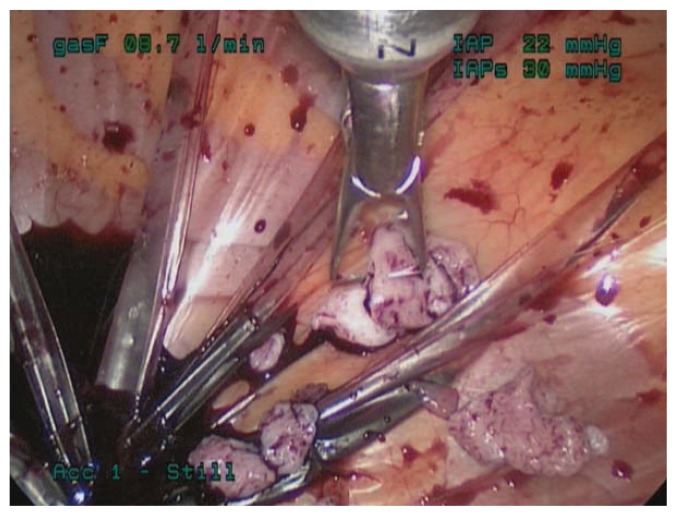

Even with a careful preoperative workup, some malignancies will be missed. Therefore, to limit both benign and malignant uterine tissue dissemination, morcellation can be contained within a bag. Several such techniques have been described. For example, specimens can be placed in a bag and morcellated by hand either through the vagina or through a minilaparotomy incision (see Figure 2). Alternatively, power morcellation can be performed inside a bag (see Figure 3).5 In 2014 Cohen et al. described the safety and feasibility of power morcellation within a large insufflated containment bag, and then in a follow-up study demonstrated negative cytologic washings after morcellation in vitro.50, 51 In 2015, Winner et al. found that morcellation within an insufflated bag took twenty minutes longer than uncontained morcellation, with no increase in complications.52 And in 2016, Cohen et al. published a prospective in vivo study in which uterine tissue was stained with dye before morcellation, and the pelvis was inspected after morcellation.53 Dye/tissue leakage was noted in 7 out of 76 cases, although the authors noted that most of the dye leakage was likely due to the method of introduction; actually spillage of tissue fragments was only noted in one case. Together, these studies indicate that power morcellation within a containment bag is feasible and effective, although efforts should be made to improve the technique. In 2016, the FDA approved the first bag for contained morcellation.54

Figure 2.

Hand morcellation through a minilaparotomy incision, contained within a bag.

Figure 3.

Power morcellation contained within an insufflated bag.

Currently, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American Association of Gynecologist Laparoscopists (AAGL) all suggest bags as potential solutions to prevent dissemination of tissue.55,56,57 However, ACOG and AAGL also warn that these techniques require advanced laparoscopic skill and that appropriate training and credentialing are important considerations.

Conclusions

Uterine morcellation is sometimes required to perform a hysterectomy via a minimally invasive approach. Morcellation has become controversial recently because of concerns regarding dissemination of occult malignancy. However, laparoscopic hysterectomy results in significantly less morbidity and mortality than open hysterectomy. Potential solutions include a careful preoperative workup and performing morcellation contained within a bag. New devices and techniques that allow surgeons to offer more women the benefits of a minimally invasive approach should be further investigated and encouraged.

Biography

Brooke Winner, MD, Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecological Surgery, Assistant Professor, and Scott Biest, MD, Director, Division of Minimally Invasive Gynecological Surgery, Associate Professor; both in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Washington University School of Medicine.

Contact: winnerb@wudosis.wustl.edu

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

References

- 1.Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (8) 2009 Jul;(3):CD003677. doi(3):CD003677. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright KN, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI. Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2012 Oct-Dec;16(4):519–524. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13462882736736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion No. 444. Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;114(5):1156–1158. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c33c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiser A, Holcroft CA, Tolandi T, Abenhaim HA. Abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign diseases: evaluation of morbidity and mortality among 465,798 cases. Gynecological surgery. 2013;10:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kho KA, Anderson TL, Nezhat CH. Intracorporeal Electromechanical Tissue Morcellation A Critical Review and Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:787–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2014. [Accessed 04/07, 2014]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm393576.htm.

- 7.Milad MP, Milad EA. Laparoscopic Morcellator-Related Complications. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013 Dec;:9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larrain D, Rabischong B, Khoo CK, Botchorishvili R, Canis M, Mage G. “Iatrogenic” parasitic myomas: unusual late complication of laparoscopicmorcellation procedures. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010 Nov-Dec;17(6):719–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nezhat C, Kho K. Iatrogenic myomas: new class of myomas? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010 Sep-Oct;17(5):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilger WS, Magrina JF. Removal of pelvic leiomyomata and endometriosis five years after supracervical hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;108(3 Pt 2):772–774. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000209187.90019.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kho KA, Nezhat C. Parasitic myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;114(3):611–615. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b2b09a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda A, Mori M, Sakai K, Mitsui T, Nakamura H. Parasitic peritoneal leiomyomatosis diagnosed 6 years after laparoscopic myomectomy with electric tissue morcellation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Nov-Dec;14(6):770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepilian V, Della Badia C. Iatrogenic endometriosis caused by uterine morcellation during a supracervical hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Nov;102(5 Pt 2):1125–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnez O, Squifflet J, Leconte I, Jadoul P, Donnez J. Posthysterectomy pelvic adenomyotic masses observed in 8 cases out of a series of 1405 laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Mar-Apr;14(2):156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Burke W, Cohen CJ, Wright JD. The utility of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Jul;110(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Pan L, Wang X, Dai Z, Huang H, Guo L, Shen K, Lian L. Clinical characteristics of endometrial stromal sarcoma from an academic medical hospital in China. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010 Dec;20(9):1535–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K, Maruo T. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002 Jul-Aug;12(4):354–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leibsohn S, d’Ablaing G, Mishell DR, Jr, Schlaerth JB. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Apr;162(4):968–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91298-q. discussion 974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Mar;83(3):414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takamizawa S, Minakami H, Usui R, Noguchi S, Ohwada M, Suzuki M, et al. Risk of complications and uterine malignancies in women undergoing hysterectomy for presumed benign leiomyomas. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48(3):193–196. doi: 10.1159/000010172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiter RC, Wagner PL, Gambone JC. Routine hysterectomy for large asymptomatic uterine leiomyomata: a reappraisal. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Apr;79(4):481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, Richard S, Zorn K, Sukumvanich P. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation. Gynecologic oncology. 2012;127(1):S29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamikabeya TS, Etchebehere RM, Nomelini RS, Murta EF. Gynecological malignant neoplasias diagnosed after hysterectomy performed for leiomyoma in a university hospital. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2010;31(6):651–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidman MA, Oduyebo T, Muto MG, Crum CP, Nucci MR, Quade BJ. Peritoneal dissemination complicating morcellation of uterine mesenchymal neoplasms. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leibsohn S, d’Ablaing G, Mishell DR, Jr, Schlaerth JB. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Apr;162(4):968–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91298-q. discussion 974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Mar;83(3):414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takamizawa S, Minakami H, Usui R, Noguchi S, Ohwada M, Suzuki M, et al. Risk of complications and uterine malignancies in women undergoing hysterectomy for presumed benign leiomyomas. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48(3):193–196. doi: 10.1159/000010172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiter RC, Wagner PL, Gambone JC. Routine hysterectomy for large asymptomatic uterine leiomyomata: a reappraisal. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Apr;79(4):481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowland M, Lesnock J, Edwards R, Richard S, Zorn K, Sukumvanich P. Occult uterine cancer in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy with morcellation. Gynecologic oncology. 2012;127(1):S29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamikabeya TS, Etchebehere RM, Nomelini RS, Murta EF. Gynecological malignant neoplasias diagnosed after hysterectomy performed for leiomyoma in a university hospital. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2010;31(6):651–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinha R, Hegde A, Mahajan C, Dubey N, Sundaram M. Laparoscopic myomectomy: do size, number, and location of the myomas form limiting factors for laparoscopic myomectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung F, Terzibackian JJ. Re “The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma”. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(1):172–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Apr, 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989–1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Apr;93(1):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yildirim Y, Inal MM, Sanci M, Yildirim YK, Mit T, Polat M, et al. Development of uterine sarcoma after tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer: report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005 Nov-Dec;15(6):1239–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang Z, Matsumoto S, Ae K, Kawaguchi N, Yoshikawa H, Ueda T, et al. Postradiation soft tissue sarcoma: a multiinstitutional analysis of 14 cases in Japan. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9(3):242–246. doi: 10.1007/s00776-004-0768-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart EA, Morton CC. The genetics of uterine leiomyomata: what clinicians need to know. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Apr;107(4):917–21. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000206161.84965.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamoxifen and uterine cancer. ACOG Committee Option No. 336. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, Warren MB, Glenn GM, Turner ML, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet. 2003 Jul;73(1):95–106. doi: 10.1086/376435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu CL, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Furukawa K, Seddon JM, Stovall M, et al. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009 Apr 15;101(8):581–591. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Mar;83(3):414–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baird DD1, Garrett TA, Laughlin SK, Davis B, Semelka RC, Peddada SD. Short-term change in growth of uterine leiomyoma: tumor growth spurts. Fertil Steril. 2011 Jan;95(1):242–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JY, Park SK, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122(2):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George S, Barysauskas C, Serrano C, Oduyebo T, Rauh-Hain AJ, Del Carmen MG, et al. Retrospective cohort study evaluating the impact of intraperitoneal morcellation on outcomes of localized uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28844. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright Jason D, MD, Tergas Ana I, MD, MPH, Burke William M, MD, Cui Rosa R, Ananth Cande V, PhD, MPH, Chen Ling, MD, MPH, Hershman Dawn L., MD, MS Uterine Pathology in Women Undergoing Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy Using Morcellation. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1253–125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, et al. Updated Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 2013 Apr;121(4):829–846. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: Management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Apr;121(4):891–896. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000428646.67925.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McPencow AM, Erekson EA, Guess MK, Martin DK, Patel DA, Xu X. Cost-effectiveness of endometrial evaluation prior to morcellation in surgical procedures for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jul;209(1):22.e1–22.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen SL, Einarsson JI, Wang KC, Brown D, Boruta D, Scheib SA, Fader AN, Shibley T. Contained power morcellation within an insufflated isolation bag. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Sep;124(3):491–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen SL, Greenberg JA, Wang KC, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR, Pozner CN, Hoover N, Einarsson JI. Risk of Leakage and Tissue Dissemination With Various Contained Tissue Extraction (CTE) Techniques: An in Vitro Pilot Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014 Sep-Oct;21(5):935–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winner B, Porter A, Velloze S, Biest S. Uncontained Compared With Contained Power Morcellation in Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct;126(4):834–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen SL, Morris SN, Brown DN, Greenberg JA, Walsh BW, Gargiulo AR, Isaacson KB, Wright KN, Srouji SS, Anchan RM, Vogell AB, Einarsson J. Contained tissue extraction using power morcellation: prospective evaluation of leakage parameters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214(2):257.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm494650.htm

- 55.ACOG. Power Morcellation and Occult Malignancy in Gynecologic Surgery: A Special Report. 2014 May; [Google Scholar]

- 56.SGO. Position Statement: Morcellation. 2013 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- 57.AAGL. Morcellation During Uterine Tissue Extraction. 2014 May; [Google Scholar]