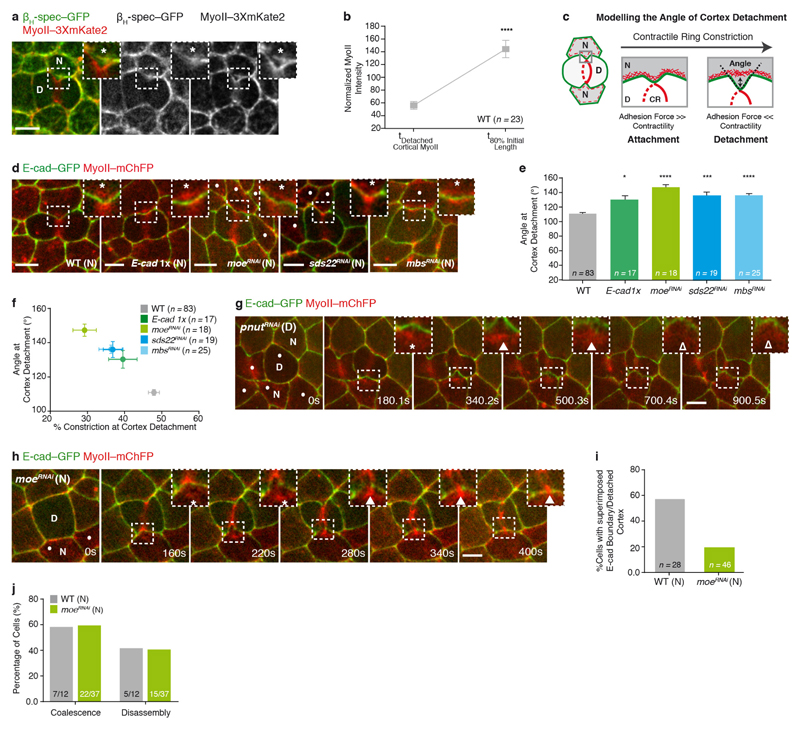

Extended Data Figure 3. Contraction of the detached cortical MyoII is not sufficient to sustain MyoII accumulation in the neighbours.

a, βH-spectrin–GFP (βH-spec–GFP) and MyoII–3 × mKate2 distribution upon contractile ring constriction. Asterisk denotes co-localization of MyoII–3 × mKate2 and βH-spec–GFP away from the ingressing AJ. n = 103 cells (4 pupae). b, Normalized MyoII intensity of the detached cortical MyoII and at 80% of the initial cell diameter in wild-type dividing cells (4 pupae). c, Schematic representation of the theoretical model describing cortex detachment in the neighbours. The AJs are highlighted in green, while the actomyosin cortex is shown in the red dashed line and in further detail in the insets. CR denotes the contractile ring. Double arrow indicates separation of the actomyosin cortex from the AJ—cortex detachment. Dashed black lines indicate the angle formed by the ingressing AJ. To probe the potential role of cortex detachment for MyoII accumulation in the neighbours, we analysed theoretically the detachment event. The cortex is a contractile layer lining the AJ, thus if it becomes curved, either because of an external deformation (that is, contractile ring constriction in the dividing cell) or a pressure difference between two cells (as observed during blebbing), this produces inward forces perpendicular to the membrane that need to be balanced by adhesion to prevent cortex detachment. The biophysical role of E-cad in this membrane–cortex interaction has been studied in vitro39, but to a lesser extent in vivo. Following the classical active gel theory10,40,41, we model the cortex as a thin viscous layer, of thickness h. γ is the local tension in the cortex, χ is the contractility due to MyoII motor power-stroke, and η is the cortical viscosity. Thus, along the direction x parallel to the membrane, the tension γ is the sum of active and viscous contributions γ = h(χ + η∂xv), with v the local velocity in the layer, under the lubrication regime40. If we consider a cortex connected to an AJ that can be curved with local curvature κ(x, t), in the quasi-static regime of the ingressing AJ during cytokinesis39, the cortex will detach if the normal forces γκ are greater than the maximal adhesion force density fc, which is proportional to the adhesion strength between the cortex and the membrane, as well as the local concentration c(x) of linker proteins. This is analogous to the de Gennes criteria for the unbinding of adhesive vesicles42. Therefore, for constant tension and adhesion strength, one expects the cortex to detach once a well-defined curvature κc, imposed by the contractile ring, is reached, such that κc = fc/γ. Thus, the model predicts that the critical curvature of cortical detachment can be modulated in vivo: the maximal curvature at detachment should increase with either an increase in membrane–cortex attachment, or a decrease in cortical tension (and vice versa). We tested this model by manipulating experimentally either cortical tension or membrane–cortex attachment (d–f). As curvature cannot be robustly defined in the ingressing AJ given the length scales examined, we alternatively measured the angle θ between the two sides of the ingressing junction (c). With d0 being the characteristic width of the ingressing region, this angle is related to curvature via κ ∝ (π − θ)/d0. To manipulate the adhesion force, we analysed cortex detachment in moeRNAi neighbours, as well as in E-cad heterozygous background (E-cad1x). Moesin is the only ERM protein in flies and it has an essential role in membrane–cortex attachment, since it directly binds both F-actin and the membrane43. As predicted theoretically, upon moeRNAi or in the E-cad1x mutant condition, cortex detachment occurs at higher angles than in wild-type neighbours; thus, the initially detached cortical MyoII is localized further away from the ingressing membrane during contractile ring constriction (d, e and h). Similarly, increasing the neighbours’ contractility by generating either sds22RNAi neighbours, which increases phospho-MyoII and phospho-Moe at the AJs44, or mbsRNAi neighbours, which globally increases phospho-MyoII by blocking the activity of the MyoII phosphatase45, results in cortex detachment at higher angles (d, e). Moreover, the angle of cortex detachment in these experimental conditions anti-correlates with the amount of constriction at detachment (f). Altogether, these data suggest that a balance between the adhesion force, cortex contractility and local membrane curvature regulates cortex detachment, in response to the pulling forces generated in the dividing cell. d, E-cad–GFP and MyoII–mChFP localization at cortex detachment in wild-type (n = 83 cells, 11 pupae), E-cad1x heterozygous mutant (n = 17 cells, 2 pupae), moeRNAi (n = 18 cells, 6 pupae), sds22RNAi (n = 19 cells, 5 pupae) and mbsRNAi (n = 25 cells, 6 pupae) neighbours. Dots indicate moeRNAi, sds22RNAi or mbsRNAi cells, marked by the absence of cytosolic GFP. Asterisks denote separation of MyoII–mChFP and E-cad–GFP signals at the ingressing region. e, Angle of cortex detachment in wild-type, E-cad1x, moeRNAi, sds22RNAi and mbsRNAi neighbours (11, 2, 6, 5 and 6 pupae, respectively). For all conditions, except E-cad1x, the dividing cell is wild-type. Note that the rate of constriction is similar for wild-type and E-cad1x cells and no detectable defects were observed during cytokinesis. f, Anti-correlation between the angle of cortex detachment (in e) and the amount of contractile ring constriction at detachment in wild-type, E-cad1x, moeRNAi, sds22RNAi and mbsRNAi neighbours (11, 2, 6, 5, pupae, respectively). Slope is −1.97 ± 0.15 (R2 = 0.98). P < 0.001, F-test for a slope different from 0. g, E-cad–GFP and MyoII–mChFP localization in a pnutRNAi dividing cell and its neighbours during cytokinesis. Filled arrowheads indicate transient MyoII–mChFP accumulation in the neighbours; open arrowheads denote reduced MyoII–mChFP accumulation in the neighbours. n = 10 out of 20 cells (5 pupae). h, E-cad–GFP and MyoII–mChFP localization in the dividing cell and its moeRNAi neighbour. In g and h, dots denote pnutRNAi (g) and moeRNAi (h) cells, marked by the absence of cytosolic GFP, and asterisks denote separation of MyoII–mChFP and E-cad–GFP signals at the ingressing AJ. At t = 208 s, arrowhead indicates the transient accumulation of MyoII–mChFP at the detached cortex; at t = 340 s and 400 s, arrowheads indicate the re-localization of the MyoII–mChFP accumulation near the boundary between high and low E-cad–GFP (see Supplementary Video 4c). n = 18 cells (6 pupae). i, Percentage of wild-type and moeRNAi neighbours (11 and 20 pupae, respectively), where the detached cortex and the E-cad boundary are superimposed. j, Percentage of wild-type and moeRNAi neighbours (7 and 17 pupae, respectively), where the detached cortex either coalesces with the MyoII accumulation positioned at the E-cad boundary, or disassembles during cytokinesis (see Supplementary Video 4d). n denotes number of cells throughout. n/n indicates number of cells/total number of cells. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Student’s t-test (b) and Kruskal–Wallis test (e). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Scale bars, 5 μm.