Efforts to engage patients and stakeholders are a ubiquitous element of Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)’s broader research program. The focus of that research is comparative effectiveness research that is built on what is important to patients. When PCORI began operations in 2011, it made an unwavering commitment to patient engagement while, at the same time, acknowledging that there was no proven recipe for doing so effectively. There was valuable experience in the field of community-based participatory research, but little evidence and no road map for applying this experience to the requirements of building data networks or designing and conducting comparative effectiveness studies.

For this Special Issue, we invited research networks across the United States that are part of PCORnet to describe their engagement strategies in detail and to bring out challenges, limitations, successes, and failures. The 10 papers offer an important body of knowledge about how to engage stakeholders in governance and implementation of research, and on the state of the science of patient and multistakeholder engagement. These papers, encompassing 6 Clinical Data Research Networks (CDRNs), 3 Patient-Powered Research Networks (PPRNs), and 1 PCORnet demonstration project, represent a diversity of approaches in some of the earliest applications of the science of engagement to patient-centered outcomes research (PCOR).

Among the PCORnet partner networks the goals of stakeholder engagement, and the methods used to accomplish these goals, were diverse. Some PPRNs, such as Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners (CCFA PPRN) and the MoodNetwork (Sylvia et al1) focused on engagement to improve participation in their research networks. Using focus groups and interviews, the CCFA PPRN sought to understand patient needs and preferences for how to develop the network and improve engagement using the participation portal. Similarly, the MoodNetwork investigators conducted a large survey (over 4000 participants) to understand patient perspectives regarding research and enrollment in this online network.

Other partner networks focused on innovative approaches for engagement to develop governance mechanisms. For example, Arthritis Patient Partnership with Comparative Effectiveness Researchers (Nowell et al2) evaluated the experience of patient governors to improve governance processes that were originally developed in collaboration between Principal Investigators and members of the community. Greater Plans Collaborative (GPC) used different groups’ discussion methods—World Café (group discussion) and Future Search (paired discussion)—to explore and delineate key dimensions of engagement that may contribute to a framework for communication (Kimminau et al3).

Another group of networks implemented tools for increasing interaction among patients and stakeholders and leveraging their engagement to elicit research priorities and improve study design. The methods were diverse, sometimes experimental and, not surprisingly, met with varying degrees of success and sustainability depending on the stakeholders engaged and overall network structure. The New York City Clinical Data Research Network (NYC-CDRN) held listening sessions of groups of clinicians and patients to explore the use of big data in health research (Goytia et al4). Research Action for Health Network (REACHnet) used stakeholder advisory groups who met over multiple meetings to discuss research priorities and set parameters to communicate to researchers interested in designing person-centered studies related to those priorities (Haynes et al5). Mid-South CDRN demonstrated a unique “community engagement studio” method which enables researchers to work closely with community members in focused sessions as they design studies. Lastly, Patient-centered SCAlable National Network for Effectiveness Research (pSCANNER) implements online modified Delphi panels, a deliberative and iterative approach to attaining consensus with discussion and statistical feedback, to engage large numbers of patients, caregivers, clinicians, and researchers in structured activity to determine research priorities (Kim et al6).

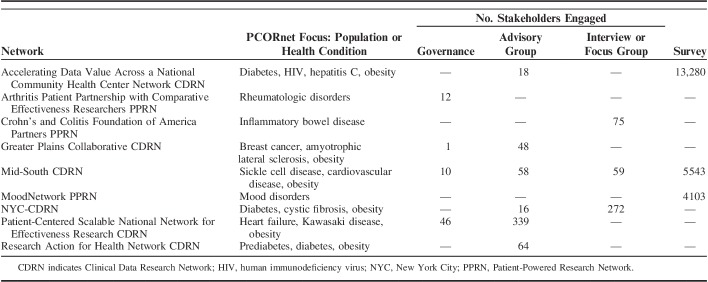

One interesting theme seen within several of the networks is that engagement using multilevel strategies allows for matching participation opportunities to the varying interests, capacity, and desires of participants. Most of the networks use more than 1 engagement strategy. Often, engagement in governance and advisory groups involved relationship building and occurred over longer periods of time. In contrast, advice on specific issues or projects occurred via interviews, focus groups, surveys, or one-time meetings (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Scale of Engagement by Network

Three papers describe comprehensive multilevel strategies. Warren et al,7 report on such an approach in Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE). Patient stakeholders in ADVANCE sit on the governing committee to develop policies, are members of a committee that select and oversee research projects, and serve as “ambassadors” to mentor less experienced stakeholders. Wilkins et al,8 describe the Mid-South CDRN’s 4-level approach to engagement in which patients can have deep involvement in research and network oversight, provide ongoing input on research questions and proposals, act as periodic consultants to investigators, or have a lower level of involvement as one-time participants in interviews or respondents to surveys. Finally, pSCANNER, by Kim and Helfand,6 offers detailed descriptions of high-touch (eg, in person), long-term engagement strategies for members of stakeholder governing boards and condition-specific advisory boards; high-tech, shorter-term but intensive online panels for setting consensus research priorities, and codesign teams that design studies focused on those research priorities.

Another theme is the ambitious size and scale of engagement in research. Table 1 summarizes how many stakeholders were engaged in each study in 4 categories: in governance and decision making, in advisory committees providing input over a period of time, and in one-time engagements such as with interviews or surveys. Examples of studies that leverage advice from a steering committee or advisory group with 10–18 individuals including patients and clinicians might not be unusual. Attempts at engagement with dozens to hundreds of advisors with responsibilities beyond being a subject of research are rare.

We believe that researchers can learn from the frank assessment of challenges and limitations that these investigators encountered. Despite best efforts, the patient stakeholders engaged were not as diverse as the patient populations they represent. A number of authors recognize the need to educate patient stakeholders about research so that they can more meaningfully contribute to discussions. However, as patients become more educated about research and involved in governance, they may in fact become less able to represent broader patient perspectives. The large number of stakeholders engaged in these networks represents a tremendous investment of resources which also presents a challenge. Although grant funding may support engagement in the short-term, sustainability will require ongoing funding so that improvements in research from engagement are not lost. In addition, there is a lack of formal evaluation of engagement strategies. Most of the papers rely on descriptive process measures such as number of participants, number of meetings, demographics, and qualitative data to assess performance. The science of engagement needs better measures and methods of evaluation to move the field forward.

Finally, these articles report an incipient but important findings on the currency of comparative effectiveness research, or PCOR. PCOR recognizes “the diverse nature of real-world patients” (as REACHNet put it) and the general goal that research should reflect the needs and priorities of patients. These principles are easy to identify with and were universally accepted by patients across the networks, but they are not the only principles that underlie PCOR, which focuses on comparing alternative treatments to identify which treatments work best when taking account of each individual’s characteristics and preferences. In their interactions with researchers and other stakeholders, the patient communities engaged in these programs described wide-ranging priorities, such as reducing stigma, increasing access to care, preventing progression of disease, improving patients’ understanding of medical information, alleviating symptoms, and redesigning delivery systems. But in articulating their priorities and needs, they also endorsed other foundational concepts of PCOR. REACHNet, for example, prioritized “the effectiveness of weight loss programs for different types of people (personality, body type, preferences, age, etc.).” The CCFA PPRN asserted that comparative information about treatment alternatives would lead to better health decisions and outcomes, and that should measure the success rates of the varying combinations of medications, alternative treatments, and diet/lifestyle approaches they have shaped as “experimenters” learning from their own experience.

As the field learns from these early experiences, lessons can be adapted and applied throughout the research continuum. If PCORI can build on these insights, it will fulfill the promise of comparative effectiveness research: to identify what clinical and public health interventions work best for improving health.

Footnotes

K.K.K. was funded in part by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Contract CDRN-1306-04819. M.H. conducted this work as a member of the PCORI Methodology Committee but did not receive funding for that activity. Both authors have affiliations with or funding from PCORI.

The authors served as external (guest) editors of this series. The views expressed in this article are those of the listed authors and do not represent those of the Veterans Affairs Health System, PCORI, or other editors of this series.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000789. Sylvia LG, Hearing CM, Montana RE, et al. MoodNetwork: An innovative approach to patient-centered research. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S48–S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000814. Nowell WB, Curtis JR, Crow-Hercher R. Patient governance in a patient-powered research network for adult rheumatologic conditions. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S16–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000772. Kimminau KS, Jernigan C, LeMaster J, et al. Patient vs. community engagement: emerging issues. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S53–S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goytia CN, Kastenbaum I, Shelley D, et al. A tale of 2 constituencies: exploring patient and clinician perspectives in the age of big data. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S64–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000785. Haynes SC, Rudov L, Nauman E, et al. Engaging stakeholders to develop a patient-centered research agenda: lessons learned from the research action for health network (REACHnet). Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S27–S32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000790. Kim KK, Khodyakov D, Marie K, et al. A novel stakeholder engagement approach for patient-centered outcomes research. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000791. Warren NT, Gaudino JA Jr, Likumahuwa-Ackman S, et al. Building meaningful patient engagement in research: case study from ADVANCE clinical data research network. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S58–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000953. Wilkins CH. Effective engagement requires trust and being trustworthy. Med Care. 2018;56(suppl 1):S6–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]