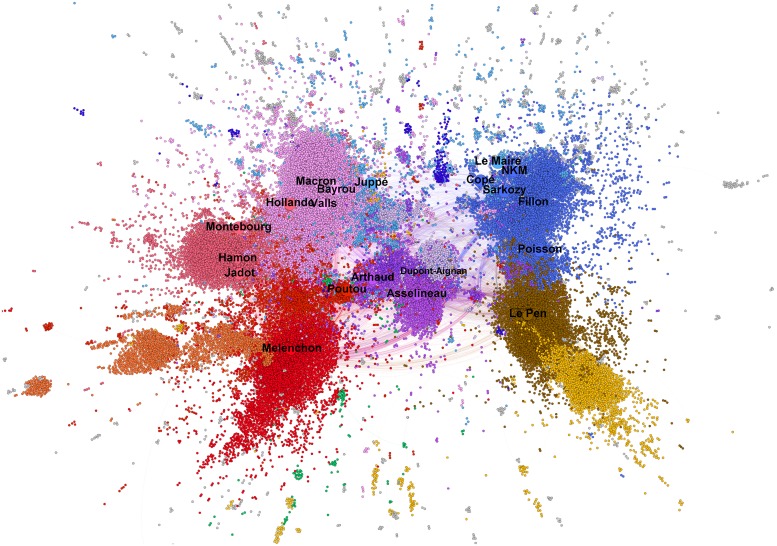

Fig 4. 3-communities in the French political environment on the day of the first round of elections (T = [9 April 2017–23 April 2017]).

The environment is highly fragmentary and multi-polar, and the main political forces are represented (the percentages shown correspond to the scores obtained in the first round): Mélenchon and France Insoumise (bright red—19.58%), Hamon and the Parti Socialiste (light red—6.36%), Macron and En Marche! (pink—24.01%), Fillon and Les Républicains (blue—20.01%), Le Pen and the Front National (brown—21.30%), Dupont-Aignan and Debout la France (lilac—4.7%). In the case of the “small” candidates, Asselineau (0.92%) and Arthaud (0.64%) are located inside the same community (purple), Poutou (1.09%) is positioned close to Mélenchon, but does not have a real Twitter community. It can be noted that not only is Bayrou located inside Macron’s community, which is not surprising in view of their unification on February 23, 2017, but also that Juppé, who was previously a candidate for the Les Républicains primary election, is considerably closer to the community of Macron than to that of Fillon and Sarkozy. His “lieutenant” Edouard Philippe, was later to become Macron’s Prime Minister. There are in addition two significant communities that are not labeled with a political leader. Colored orange, to the left of the figure and close to Mélenchon’s community, one can discern a community identified as being associated with the Discorde Insoumise, a video-game community which played an important role in Mélenchon’s campaign. Coloured yellow, at the bottom-right of the figure, close to Le Pen’s community, we identify a community of English-speaking populist and nationalist accounts which strongly supported Le Pen. This community is itself made up from sub-communities, in particular English-speaking supporters of Le Pen, Trump supporters, and UK pro-Brexit supporters. One can also observe significant differences with respect to the pre-presidential campaign of 2016 (Fig 1): in addition to the “left-right” axis, which was dominant at that time, a new (“vertical” on the map) axis appears to be significant, distinguishing between parties with a nationalist, patriotism or protectionist focus and those accepting or adhering to the globalization of economic trade. Note that the fact that the “small” candidates are located at the center of the map should not be interpreted as a form of centrality. Only topological adjacencies are significant on this type of graph. As the “small” candidate communities are not well connected with the other communities, they are located at the center as a consequence of the spatialization algorithm used to make the graph. File A4 at DOI: 10.7910/DVN/AOGUIA provides an editable version of this graph.