Abstract

Background

Fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) are widely used and recommended for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Fecal hemoglobin (Hb) may degrade with long transport durations and high ambient temperatures, potentially reducing sensitivity to detect CRC and its precursors. This study aimed at investigating the impact of temperatures and sample travel times on diagnostic performance of a quantitative FIT for detection of advanced neoplasms (AN, CRC, or advanced adenoma).

Methods

Participants of screening colonoscopy in south-western Germany conducted a quantitative FIT prior to bowel preparation between February 2012 and June 2016. From available locations and dates of stool sampling and transport, maximum ambient temperatures were linked to 2,870 participants aged 50–79 years and sample return durations were recorded. The impact of ambient temperatures and return duration on FIT sensitivity and specificity was assessed for five different cutoffs between 10 and 25 µg Hb/g feces.

Results

At a positivity threshold of 20 µg Hb/g feces, overall sensitivity and specificity for detecting any AN were 40% (95% CI, 35–47%) and 95% (95% CI, 94–96%), respectively. Inverse associations between maximum ambient temperature (median 18.1°C, inter-quartile range [IQR] =11.4–24.9°C) and sensitivity of FIT were observed which were stronger at higher cutoffs. Sample return durations (median 6 days, IQR =4–8 days) were not associated with variable sensitivities or specificities.

Conclusion

Hb degredation during fecal sample transportation in summer months may be of some concern for diagnostic performance of the FIT evaluated under routine conditions in a middle-European climate.

Keywords: advanced colorectal neoplasm, fecal immunochemical test, ambient temperature, sample travel time, sensitivity, hemoglobin degradation

Plain language summary

Fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening are typically conducted at home and sent to a laboratory for analysis. By measuring human hemoglobin in stool, FITs detect a significant share of advanced neoplasms (CRC or advanced adenoma). However, hemoglobin is not stable when exposed to high temperatures for a longer time, potentially decreasing sensitivity of FIT. Previous studies indicated that positivity of FIT decreases with higher ambient temperatures. By contrast, associations between ambient temperatures and sensitivity and specificity of FIT, using colonoscopy as gold standard, have not yet been assessed. Thus, we assessed the associations between ambient temperature, sample return time, and sensitivity and specificity of a widely used fecal immunochemical test (FOB Gold) using various cutoffs for detecting advanced colorectal neoplasms in a large screening population in south-western Germany.

Sensitivity and specificity at five different cutoffs were examined among 2,870 participants of screening colonoscopy who collected a fecal sample for FIT prior to large bowel preparation. Inverse associations between maximum ambient temperature and sensitivity of FIT were observed which were larger at higher cutoffs. Sample return durations were not associated with sensitivities or specificities. In conclusion, avoidance of summer days when using fecal immunochemical tests requiring laboratory analysis might help ensuring high sensitivity of the investigated FIT in a middle-European climate for detecting AN.

Introduction

Fecal immunochemical tests (FITs) are widely used and recommended for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.1,2 They measure the hemoglobin (Hb) concentration in fecal samples that are typically sent to a laboratory for analysis. Although FITs were shown to clearly outperform traditional guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests in terms of diagnostic performance,3–5 potential Hb degradation, especially, during longer sample travel times and at higher ambient temperatures is of potential concern, as it may reduce sensitivity to detect CRC or its precursors.

Several studies examined the impact of high vs low outside (ambient) temperatures on FIT positivity6–14 and the effect of delayed sample travel and processing on Hb concentrations.13,15 To date, only one study9 examined the impact of both temperatures and travel time on positivity and Hb concentrations of FITs conducted at home and sent for analysis and found no association between sample return time and FIT positivity. To our knowledge, no study to date assessed the impact of both temperatures and travel times of FIT on sensitivity and specificity for detecting CRC or its precursors using colonoscopy as reference standard. In our study, we examined the association between outside temperatures, sample travel times, and sensitivity and specificity of a quantitative FIT in a large cohort of participants of screening colonoscopy using results of screening colonoscopy as reference standard for all participants.

Methods

Study design, study population, and data collection

Our analyses were conducted among participants of the BliTz study (Begleitende Evaluierung innovativer Testverfahren zur Darmkrebs-Früherkennung). Details of the BliTz study have been reported elsewhere.16–19 In brief, BliTz is a large ongoing study in south-western Germany in which stool samples are collected prior to bowel preparation among participants of screening colonoscopy, and stool tests are evaluated by direct comparison with colonoscopy results. In Germany, screening colonoscopy is offered from age 55 years onward for men and women, although some insurance plans offer screening colonoscopy from younger age onward. Subjects are recruited at a pre-colonoscopy visit in gastroenterology practices. In addition to being asked to collect a stool sample prior to bowel preparation for colonoscopy, participants are asked to fill out a brief self-administered questionnaire including questions on basic sociodemographics, medical history, and factors potentially related to CRC risk.

The ethics committees of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University and the Physicians’ Chambers of Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland, and Hesse approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent. The current analysis included participants recruited from February 2012 until June 2016. During this period, participants received collection tubes containing Hb-stabilizing buffer (10 mg stool in 1.7 mL buffer; Sentinel Diagnostics, Milano, Italy, Ref 11561H) to collect stool samples. No changes on the buffer composition were made during the recruitment period. Stool from three different spots was to be collected from one stool sample and put in the collection tube and sealed with a screw cap. After sample collection, the tubes were to be sealed in envelopes. Participants were asked to bring the envelopes to the next post box or post office as soon as possible, from where they were mailed to the study center at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) by regular mail. After arrival, they were kept in the refrigerator at 2–8°C before transporting in a cold chain maintained by cooling pads to the central laboratory (Labor Limbach, Heidelberg, Germany) where they were analyzed. Times from stool sampling until arrival at DKFZ were recorded. Colonoscopy and histology records were obtained from the gastroenterology practices upon completion of screening colonoscopy. Colonoscopists were unaware of FIT results. Two trained extractors independently extracted findings at screening colonoscopy in a standardized manner from colonoscopy and histology records obtained from the gastroenterology practices.

Laboratory analyses

FOB Gold (Sentinel Diagnostics, Milano, Italy) was used for Hb measurements. Laboratory personnel was fully blinded with respect to colonoscopy results. Specimens were analyzed in a fully automated manner on Abbott Architect c8000. Dates of FIT conduction and the FIT result were recorded. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) between fecal sampling and arrival in DKFZ was 4 (IQR =3–5) days, and the median between arrival at DKFZ and laboratory analysis was 2 (IQR =1–3) days.

Temperature data

To estimate the outside temperature at the time of sample collection and traveling, maximum outside temperatures during the days from sampling at the locations of the gastroenterology practices and arrival at DKFZ were recorded. Subjects not providing the date of sample collection were excluded from our analyses because the outside temperatures during sample transport could not be determined. In sensitivity analyses, averages of daily maximum temperatures from sampling until arrival were used as exposure variable. Temperature data for each place and date were extracted from publicly available data of the German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst).20

Statistical analysis

Study participants were described by age, sex, and most advanced finding at screening colonoscopy. The following categories were used to classify subjects according to their most advanced finding at colonoscopy: CRC, advanced adenoma (AA), non-AA, other, or no finding. AAs were defined as adenomas matching at least one of the following criteria: size ≥1 cm, villous or tubulo-villous architecture, or high-grade dysplasia.

Sensitivities and specificities were calculated for any advanced neoplasm (AN, ie, CRC or AA) as outcome. Sensitivity was defined as the share of FIT-positive subjects with AN among all subjects with AN. Specificity was defined as the share of FIT-negative subjects without AN among all subjects free of AN. First, sensitivities were calculated on an aggregated level by months of test conduction.

Distributions of Hb concentrations of FIT according to maximum temperature during sample travel (categories: ≤0°C, 1–4°C, 5–9°C, 10–14°C, 15–19°C, 20–24°C, ≥25°C) and according to sample travel times (categories: 1–3 days, 4–6 days, 7–9 days, 10–12 days, and 13–15 days) were assessed within groups of participants with and without AN.

Then, sensitivity and specificity were calculated according to maximum temperature during sample travel (categories: <10°C, 10–19°C, 20–24°C, ≥25°C) and according to sample travel times (categories: 1–3 days, 4–6 days, 7–9, and ≥10 days) along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for various FIT cutoffs (10, 15, 20, and 25 Hb µg/g stool) in addition to the cutoff recommended by the manufacturer (17 µg/g). In sensitivity analyses, means of daily maximum temperatures during sample travel were used rather than the actual maximum of any day from sampling until arrival.

All statistical analyses were performed using R21 version 3.3.3. The R package “binom”22 was used to calculate Clopper-Pearson 95% CIs of proportions. Primary outcome measures were FIT sensitivity for detecting advanced colonoscopy findings according to maximum outside temperature and sample travel time. As secondary outcome, FIT specificity was also examined for different temperature and travel time categories.

Results

Study population

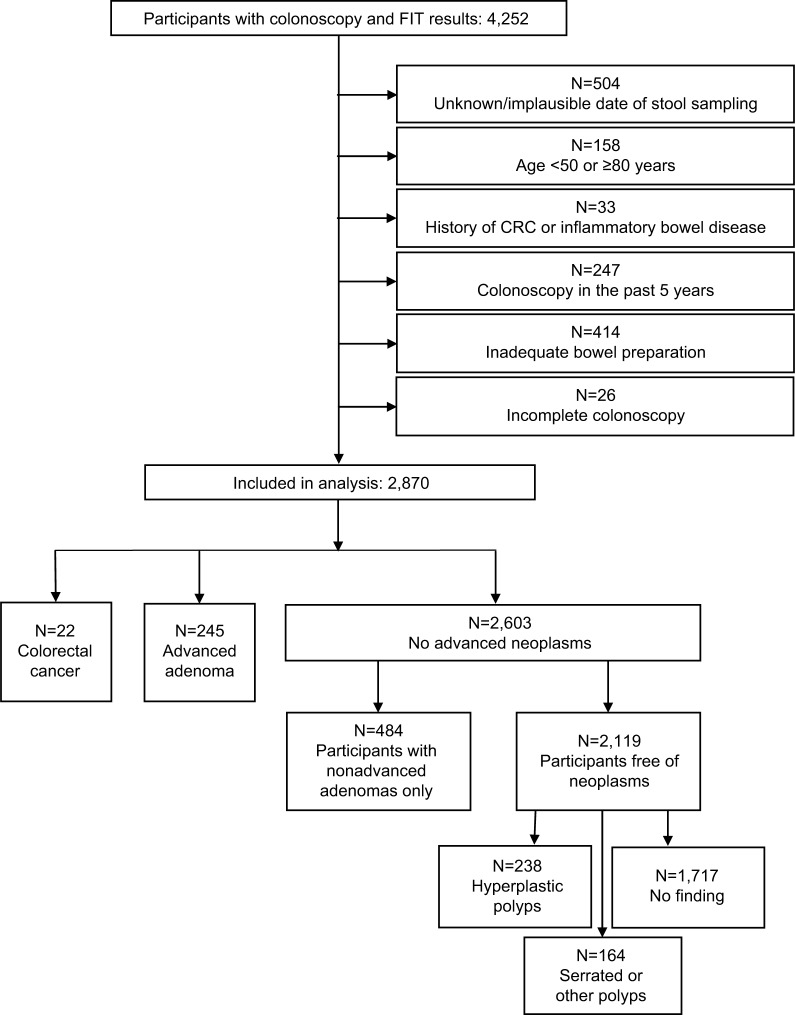

From a total of 4,252 subjects, colonoscopy and stool test results were available. A total of 2,870 subjects were finally included in the analyses after exclusion of subjects matching any of the following criteria (Figure 1): unavailable or implausible stool sampling dates (N=504, eg, sample return durations >14 days), not in the relevant age range for screening (<50 or ≥80 years, N=158), previous diagnosis of CRC or inflammatory bowel disease (N=33), colonoscopy in the preceding 5 years (N=247), inadequate bowel preparation (N=414), or incomplete colonoscopy (N=26). Almost equal shares of men (48.7%) and women (51.3%) were included in the analyses (Table 1). Mean age was 61.9 years. CRC, AA, and non-AAs as most advanced findings were found in 22 (0.8%), 245 (8.5%), and 484 (16.9%) participants, respectively. In 2,119 participants (73.8%), no neoplasms were found.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the participants in the BliTz study included in this analysis.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; FIT, fecal immunochemical test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (N=2,870), distribution of sample return times and corresponding ambient temperatures

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 50–59 | 1,347 | 46.9 |

| 60–69 | 1,028 | 35.8 |

| 70–79 | 495 | 17.3 |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 1,471 | 51.3 |

| Men | 1,399 | 48.7 |

| Most advanced finding | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 22 | 0.8 |

| Advanced adenoma | 245 | 8.5 |

| Non-advanced adenoma | 484 | 16.9 |

| No neoplasm | 2,119 | 73.8 |

| Sample travel time (days)a | ||

| 1–3 | 431 | 15.0 |

| 4–6 | 1,305 | 45.5 |

| 7–9 | 773 | 26.9 |

| 10–12 | 319 | 11.1 |

| 13–15 | 42 | 1.5 |

| Maximum temperatures during sample traveling | b | |

| ≤0°C | 14 | 0.5 |

| 1–4°C | 140 | 4.9 |

| 5–9°C | 448 | 15.6 |

| 10–14°C | 554 | 19.3 |

| 15–19°C | 443 | 15.4 |

| 20–24°C | 568 | 19.8 |

| ≥25°C | 703 | 24.5 |

| Mean of maximum temperatures during traveling | c | |

| ≤0°C | 45 | 1.6 |

| 1–4°C | 288 | 10.0 |

| 5–9°C | 559 | 19.5 |

| 10–14°C | 564 | 19.7 |

| 15–19°C | 556 | 19.4 |

| 20–24°C | 539 | 18.8 |

| ≥25°C | 319 | 11.1 |

Notes:

Travel represents time from fecal sample collection to arrival at study center;

actual maximum temperatures at any time during sample traveling;

average of daily maximum temperatures during sample traveling.

Temperatures, sample travel times, and hemoglobin concentrations

Approximately, equal proportions of FITs were sent for analysis at averages of daily maximum temperatures during sample traveling below 10°C, between 10°C and 19°C, and of 20°C or higher (Table 1). The median (IQR) of daily maximum temperatures was 18.1°C (11.4–24.9°C). At least 25°C was measured at any day from sampling until arrival in 24% (703/2,870) of subjects, and in 11% of subjects (319/2,870), the average of daily maximum temperatures from sampling to arrival exceeded 25°C. In participants with AN, some differences in median fecal Hb concentrations were observed between stool samples that were exposed to 25°C or higher maximum outside temperatures at any time during traveling and samples collected and traveling at outside temperatures <10°C (13.1 vs 18.7 µg/g) (Table 2). A small difference was observed in subjects without AN with median Hb concentrations of 4.9 µg/g when temperatures exceeded 25°C compared to 5.3 µg/g during cooler days. No differences in median Hb concentrations were seen when focusing on averages of daily maximum temperatures, neither in subjects with nor without AN.

Table 2.

Median hemoglobin concentration (interquartile range, IQR) according to maximum temperature during sample travel

| Sample travel conditions | Participants with AN

|

Participants without AN

|

Total

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (IQR) [µg/g] | N | Median (IQR) [µg/g] | N | Median (IQR) [µg/g] | ||

| Actual maximum temperature (°C)a | <10 | 59 | 18.7 (7.4–41.1) | 526 | 5.3 (3.4–7.1) | 585 | 5.4 (3.6–7.7) |

| 10–19 | 92 | 10.1 (5.6–77.7) | 914 | 5.1 (2.9–7.0) | 1,006 | 5.3 (2.9–7.5) | |

| 20–24 | 50 | 10.9 (6.3–62.3) | 519 | 5.1 (3.1–7.1) | 569 | 5.4 (3.2–7.8) | |

| ≥ 25 | 66 | 13.1 (4.5–39.4) | 644 | 4.9 (2.6–7.5) | 710 | 5.1 (2.7–7.5) | |

| Average of maximum temperatures (°C)b | <10 | 87 | 10.5 (6.7–49.2) | 805 | 5.3 (3.2–7.1) | 892 | 5.4 (3.4–7.7) |

| 10–19 | 100 | 12.2 (5.9–43.5) | 1,019 | 5.1 (2.7–7.0) | 1,119 | 5.4 (2.9–7.3) | |

| 20–24 | 32 | 12.3 (5.3–49.0) | 484 | 4.9 (2.7–7.0) | 516 | 5.1 (2.7–7.5) | |

| ≥ 25 | 24 | 12.6 (4.8–36.1) | 295 | 5.1 (2.6–7.7) | 319 | 5.4 (3.1–7.8) | |

| Sample travel timec(days) | 1–3 | 47 | 8.5 (6.2–34.0) | 384 | 4.8 (2.4–7.3) | 431 | 5.1 (2.6–7.8) |

| 4–6 | 131 | 13.3 (4.8–66.6) | 1,174 | 4.6 (2.6–6.6) | 1,305 | 4.9 (2.7–7.0) | |

| 7–9 | 65 | 12.4 (6.8–49.1) | 708 | 5.6 (3.6–7.3) | 773 | 5.6 (3.7–7.8) | |

| ≥ 10 | 24 | 14.1 (6.1–39.1) | 337 | 6.0 (4.3–7.7) | 361 | 6.1 (4.4–8.0) | |

Notes:

Highest temperature at any day from sampling until arrival at study center;

mean of daily maximum temperatures at the days from sampling until arrival at study center;

travel represents time from fecal sample collection to arrival at study center.

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); IQR, interquartile range; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.

Median stool sample travel time was 6 days (IQR =4–8 days). Travel times were very similar across the different participating practices. Medians ranged from 5 to 7 days, 25% quartiles from 3 to 5 days, and 75% quartiles from 7 to 10 days. In total, 87.4% of all samples were returned within 1–9 days (Table 1). Median Hb concentrations were similar for different sample travel times, both in participants with AN and in participants without AN (Table 2).

Diagnostic performance

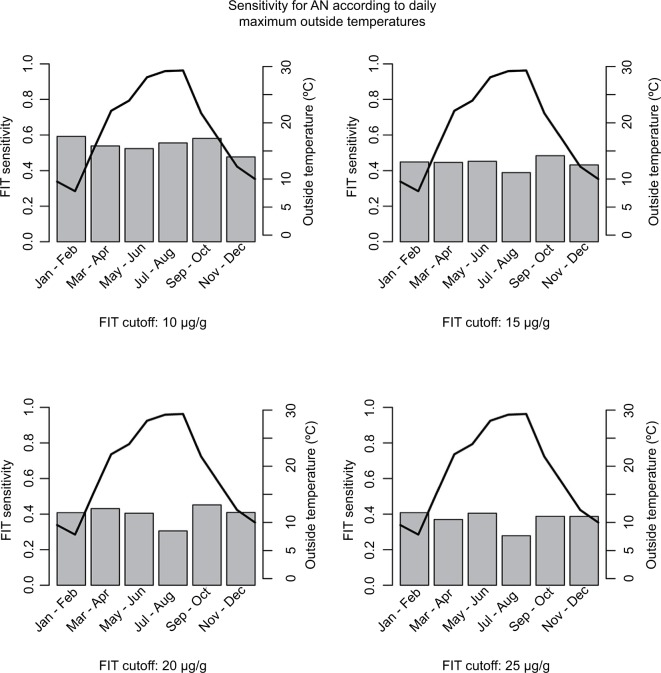

Overall sensitivity and specificity for AN at a positivity threshold of 10 Hb µg/g feces were 54% (95% CI, 48–60%) and 89% (95% CI, 87–90%), respectively. Sensitivity markedly decreased, and specificity increased with increasing FIT cutoffs, reaching 37% (95% CI, 32–44%) and 96% (95% CI, 96–97%) at a positivity threshold of 25 Hb µg/g feces. When aggregating sensitivities of FIT for AN by month of conduction, minor differences were seen when using a cutoff of 10 µg/g (Figure 2, upper left panel) and 15 µg/g (Figure 2, upper right panel). At a positivity threshold of 10 µg/g, sensitivities ranged from 48% in November and December to 59% in January and February. At FIT positivity thresholds of 15 µg/g, 20 µg/g (Figure 2, lower left panel) and 25 µg/g (Figure 2, lower right panel), differences were somewhat stronger, with apparently somewhat lower sensitivities in July and August when outside temperatures were on average higher. Nevertheless, CIs widely overlapped. For instance, at a cutoff of 25 µg/g, sensitivities ranged from 28% (95% CI, 14–45%) in July/August to 41% (95% CI, 27–56%) in January/February.

Figure 2.

FIT sensitivity for AN and maximum outside temperatures by months.

Notes: Gray bars correspond to FIT sensitivities (left scale), and black lines correspond to maximum outside temperatures (right scale).

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); FIT, fecal immunochemical test; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.

When assessing the actual daily maximum temperatures on the sample collection and travel days as exposure variable, a trend toward lower sensitivities was seen which was more pronounced at higher FIT cutoffs, with sensitivities being lower by between 5 and 11 percent units at maximum temperatures of 25°C or higher compared to maximum temperatures below 10°C in absolute terms (Table 3). There was no major variation of specificity according to maximum temperature. Also, neither sensitivity nor specificity showed any major variation according to sample travel time (Table 4).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of FIT for AN according to FIT cutoff and actual maximum temperature during sample travel

| FIT cutoff (µg/g) | Maximum temperature (°C) | Sensitivity (N=267 with AN)

|

Specificity (N=2,603 without AN)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP/NAN | % (95% CI) | TN/Nno AN | % (95% CI) | ||

| 10 | <10 | 35/59 | 59.3 (45.7–71.9) | 469/526 | 89.2 (86.2–91.7) |

| 10–19 | 47/92 | 51.1 (40.4–61.7) | 790/914 | 86.4 (84.0–88.6) | |

| 20–24 | 27/50 | 54.0 (39.3–68.2) | 450/519 | 86.7 (83.5–89.5) | |

| ≥ 25 | 36/66 | 54.5 (41.8–66.9) | 572/644 | 88.8 (86.1–91.1) | |

|

| |||||

| 15 | <10 | 30/59 | 50.8 (37.5–64.1) | 494/526 | 93.9 (91.5–95.8) |

| 10–19 | 39/92 | 42.4 (32.1–53.1) | 841/914 | 92.0 (90.1–93.7) | |

| 20–24 | 20/50 | 40.0 (26.4–54.8) | 474/519 | 91.3 (88.6–93.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 29/66 | 43.9 (31.7–56.7) | 602/644 | 93.5 (91.3–95.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 17 | <10 | 30/59 | 50.8 (37.5–64.1) | 499/526 | 94.9 (92.6–96.6) |

| 10–19 | 38/92 | 41.3 (31.1–52.1) | 849/914 | 92.9 (91.0–94.5) | |

| 20–24 | 20/50 | 40.0 (26.4–54.8) | 481/519 | 92.7 (90.1–94.8) | |

| ≥ 25 | 28/66 | 42.4 (30.3–55.2) | 606/644 | 94.1 (92.0–95.8) | |

|

| |||||

| 20 | <10 | 27/59 | 45.8 (32.7–59.2) | 505/526 | 96.0 (94.0–97.5) |

| 10–19 | 37/92 | 40.2 (30.1–51.0) | 862/914 | 94.3 (92.6–95.7) | |

| 20–24 | 20/50 | 40.0 (26.4–54.8) | 487/519 | 93.8 (91.4–95.7) | |

| ≥ 25 | 24/66 | 36.4 (24.9–49.1) | 612/644 | 95.0 (93.1–96.6) | |

|

| |||||

| 25 | <10 | 26/59 | 44.1 (31.2–57.6) | 510/526 | 97.0 (95.1–98.3) |

| 10–19 | 35/92 | 38.0 (28.1–48.8) | 877/914 | 96.0 (94.5–97.1) | |

| 20–24 | 17/50 | 34.0 (21.2–48.8) | 495/519 | 95.4 (93.2–97.0) | |

| ≥ 25 | 22/66 | 33.3 (22.2–46.0) | 618/644 | 96.0 (94.1–97.3) | |

Notes: Italic text represents results for the cutoff recommended by the manufacturer.

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); FIT, fecal immunochemical test; NAN, number of participants with advanced neoplasm; Nno AN, number of participants without advanced neoplasm; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of FIT for AN according to FIT cutoff and sample travel time

| FIT Cutoff (µg/g) | Sample travel time (days) | Sensitivity (N=267 with AN)

|

Specificity (N=2,603 without AN)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP/NAN | % (95% CI) | TN/Nno AN | % (95% CI) | ||

| 10 | 1–3 | 21/47 | 44.7 (30.2–59.9) | 324/384 | 84.4 (80.3–87.9) |

| 4–6 | 74/131 | 56.5 (47.6–65.1) | 1,047/1,174 | 89.2 (87.3–90.9) | |

| 7–9 | 37/65 | 56.9 (44.0–69.2) | 617/708 | 87.1 (84.5–89.5) | |

| ≥10 | 13/24 | 54.2 (32.8–74.4) | 293/337 | 86.9 (82.9–90.4) | |

|

| |||||

| 15 | 1–3 | 17/47 | 36.2 (22.7–51.5) | 348/384 | 90.6 (87.3–93.3) |

| 4–6 | 63/131 | 48.1 (39.3–57.0) | 1,093/1,174 | 93.1 (91.5–94.5) | |

| 7–9 | 26/65 | 40.0 (28.0–52.9) | 658/708 | 92.9 (90.8–94.7) | |

| ≥10 | 12/24 | 50.0 (29.1–70.9) | 312/337 | 92.6 (89.2–95.1) | |

|

| |||||

| 17 | 1–3 | 16/47 | 34.0 (20.9–49.3) | 353/384 | 91.9 (88.7–94.4) |

| 4–6 | 63/131 | 48.1 (39.3–57.0) | 1,100/1,174 | 93.7 (92.2–95.0) | |

| 7–9 | 25/65 | 38.5 (26.7–51.4) | 666/708 | 94.1 (92.1–95.7) | |

| ≥10 | 12/24 | 50.0 (29.1–70.9) | 316/337 | 93.8 (90.6–96.1) | |

|

| |||||

| 20 | 1–3 | 15/47 | 31.9 (19.1–47.1) | 358/384 | 93.2 (90.2–95.5) |

| 4–6 | 59/131 | 45.0 (36.3–54.0) | 1,111/1,174 | 94.6 (93.2–95.9) | |

| 7–9 | 24/65 | 36.9 (25.3–49.8) | 676/708 | 95.5 (93.7–96.9) | |

| ≥10 | 10/24 | 41.7 (22.1–63.4) | 321/337 | 95.3 (92.4–97.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 25 | 1–3 | 13/47 | 27.7 (15.6–42.6) | 366/384 | 95.3 (92.7–97.2) |

| 4–6 | 56/131 | 42.7 (34.1–51.7) | 1,122/1,174 | 95.6 (94.2–96.7) | |

| 7–9 | 23/65 | 35.4 (23.9–48.2) | 684/708 | 96.6 (95.0–97.8) | |

| ≥10 | 8/24 | 33.3 (15.6–55.3) | 328/337 | 97.3 (95.0–98.8) | |

Note: Italic text represents results for the cutoff recommended by the manufacturer.

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); FIT, fecal immunochemical test; NAN, number of participants with advanced neoplasm; Nno AN, number of participants without advanced neoplasm; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.

Results of sensitivity analyses

In addition to actual maxima at any day during sample travel, we defined exposure groups according to means of daily maximum temperatures during any day of sample travel. Using this definition, shares of FITs exposed to high temperatures (>25°C) were much smaller (266/2,870=9.3%). Similar to associations with actual maximum temperatures during sample travel, some decrease in sensitivity was observed for the two highest cutoffs when comparing highest vs lowest temperatures (9–11% units), though CIs widely overlapped. Specificities of FIT were largely constant for a given FIT cutoff at different means of daily maximum temperatures (Table S1).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between ambient temperature and performance of FIT in a CRC screening population from Germany. For a quantitative FIT conducted at home and returned by subjects to the laboratory for analysis by regular mail, Hb concentrations by outcome, sensitivity, and specificity were examined at five different cutoffs with stratification according to the maximum temperature while returning the FIT and according to different intervals of sample return durations. Hb concentrations were lower in subjects with AN when FIT samples were exposed to ≥25°C, compared to FIT samples exposed to no more than 10°C, and these differences translated into potentially clinically relevant decreases of sensitivity of ~ 5–10 percentage points, depending on the FIT cutoff. Small differences in Hb concentrations were also observed in subjects without AN, where lower Hb concentrations were measured when FIT was subject to ≥25°C. Specificities were slightly higher accordingly (by 1–2 percentage points) at ≥25°C for every cutoff. A possible explanation is degradation of Hb among subjects with non-advanced findings such as small adenomas or hyperplastic polyps. However, spurious correlations cannot be ruled out due to the rather small case numbers in each temperature group, resulting in widely overlapping CIs. In contrast to temperatures, no relevant differences in FIT results were observed between samples returned within 3 days and samples returned after more than 10 days.

Our study expands previous analyses from the BliTz study in which no differences in FIT performance had been found between fecal samples that were kept frozen until analyses and fecal samples that were sent by regular mail.14 Twofold increase of the number of the latter samples and specific consideration of actual outside temperatures at individual sample shipping rather than months of FIT conduction and individual sample transportation time enabled much more detailed analysis of the potential impact of these factors on FIT performance.

A recent laboratory experiment found that Hb remained relatively stable for up to 1 week when stored at ambient temperatures (20–22°C), whereas degradation progressed rapidly at higher temperatures.13 Thus, some decrease in sensitivity and an increase in specificity of FIT when returned at high temperatures were expected. Several previous population-based studies investigated the association between ambient temperatures and positivity, but not sensitivity and specificity of FIT,6,9–12,14 and most of them found a negative association between higher temperatures and FIT positivity. The largest study,6 with nearly 200,000 evaluated FITs conducted in Florence, Italy, indicated that a 1°C increase in temperature decreased FIT positivity by 0.7% and that detection rates for AN were by 13% lower in summer than in winter. Another finding of that study6 was that average Hb concentrations were relatively stable up to 25°C and markedly dropped at higher temperatures. Further evidence for high Hb stability in FITs up to a certain temperature threshold is provided by a large Australian study.11 Compared to cool ambient temperatures (≤17.0°C), a weak decrease in FIT positivity (odds ratio: 0.89) was observed at elevated temperatures (17.1–26.0°C). Only at even higher temperature ranges (26.1–35.0°C and >35°C), positivity decreased strongly, by 22% and 41%, respectively. A study from California12 (N=472,542) found differences in FIT positivity by month, with higher positivity rates during the winter months. Absolute differences in sensitivity of detecting CRC (estimated by record linkage with cancer registry data rather than by comparison with colonoscopy results) were small, however, ranging from 75% in June/July to 79% in December/January. Furthermore, only one FIT cutoff (20 µg/g) was examined, and the lack of a direct comparison with colonoscopy results hindered determining sensitivity for AAs or any ANs.

In our study, no consistent pattern of a decrease in FIT sensitivity was observed for above-average sample return times. Sensitivities were similar for return durations of 4–6 days (48%) and ≥10 days (50%) as they were for 1–3 days (34%) and 7–9 days (38%). Given the small case numbers in the group with 1–3 days return duration (N=47 ANs) and the claimed Hb stability for 7 days at 15–30°C,23 the most plausible explanation might be a chance finding. The apparent null result is in line with results from previous studies. One study9 examined the association between Hb concentrations and return times of FIT. In FITs conducted by screenees, no significant decrease in positivity was seen between subjects returning their FIT within <7 vs >7 days or when comparing FITs returned after 3 or more days with those returned within 2 days. In a laboratory experiment within the same study, no strong decline in Hb concentration was observed for up to 7 days of return time, with a sharp decline only after 10 and more days from sampling. In our study, the vast majority of FITs (87%) were returned within 9 days. Statistical power to quantify the potential influence of even longer return times was thereby limited, given the low number of AN cases where FITs were exposed to these conditions. Invariance of our FIT toward prolonged sample return times may in part also be explained by use of an enhanced buffer, which is claimed to ensure Hb stability for 14 days at 2–8°C and for 7 days at 15–30°C.23

The CRC detection rate in our study was 0.8% and 8.5% had AA. Several previous studies reported lower CRC prevalences (Morikawa et al,24 Chiu et al,25 and Wong et al,26 0.4% each), although other screening studies also reported higher CRC detection rates (eg, Park et al,3 1.7%; Carr et al,27 1.2%). AA detection rates in studies using the same AA definition were typically lower (Chiu et al,25 2.8%; Wong et al,26 5.2%). Possible reasons for the relatively high CRC and AA detection rates include the older age of the study population compared to other studies, conduction of the study in a high incidence country, and exclusion of subjects with a previous colonoscopy in the past 5 years who have very low neoplasia detection rates.

As a major strength of our study, colonoscopy was used as reference standard for all included subjects, allowing us to calculate sensitivities and specificities rather than positivity rates only. Sensitivities and specificities were examined at five different FIT cutoffs using the same FIT and the same buffer solution. Actual temperatures for each day from sampling until the beginning of the cold chain were used rather than monthly9,10 or seasonal6 averages. Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate the potential influence of both temperature and sample return time on sensitivity and specificity of FIT for several cutoffs. Subjects were recruited from a screening setting and did not conduct FIT or undergo colonoscopy for clarification of symptoms. Approximately 2,900 participants were included, thereof nearly 300 AN cases.

Several limitations of our study have to be kept in mind. Because only a single FIT was conducted by each subject, the hypothetical Hb concentration that would have resulted from exposure to other temperatures or travel times (counterfactual conditional) is unobservable. Investigation of actual Hb degradation would have required a series of FITs from each subject to be analyzed after exposure to a range of simulated travel durations and temperatures. Due to data protection (anonymization), temperatures were allocated by postal code of recruiting practices and not by place of residence of participants. Precision of temperature measurements was further limited to daily maximum temperatures. Although more precise than aggregated temperatures by month, actual temperatures during transport may still have differed, eg, depending on the transport conditions such as in a car with or without air conditioning. Random variation in temperatures due to unmeasurable differences in transport conditions would not introduce bias but reduce precision. Furthermore, the number of FITs conducted during very warm temperatures and returned after a very long time was small. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that a true inverse association between high temperatures and lower sensitivity of the investigated FIT would be somewhat stronger than observed on our study for moderate climate conditions such as encountered in middle Europe and even more so for countries with warmer ambient temperatures. Our analysis focused on one specific FIT and the corresponding equipment (collection tube, buffer solution, analyzer). Although standard equipment of different FITs has been shown to yield comparable results when adjusting cutoffs to achieve the same specificity,18 potentially relevant differences in Hb stability when using other kits or combinations of components thereof particularly at high temperatures cannot be ruled out. Sessile-serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) were not considered in our study because those lesions were not systematically recorded by endoscopists during the early years of study recruitment. Previous studies indicated that FITs detect only a very small share of SSA/Ps.28,29 Finally, as with any screening program, some self-selection of subjects with above-average risk (who undergo “screening” colonoscopy despite the presence of symptoms) or below-average risk (healthy user/screenee bias30) cannot be ruled out, although subjects were recruited who underwent colonoscopy for primary screening.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that Hb degradation during fecal sample transportation in summer months may be of some concern for the diagnostic performance of the FIT evaluated in our study under routine conditions in a middle-European climate. Such concern may be even more warranted in countries with a warmer climate, in which effective cooling during transport times might be indispensable, or on hot days in countries with moderate climate. In the latter countries, simple avoiding of hot days or periods for FIT testing, or concentration of FIT testing on fall, winter, and spring rather than summer might help to prevent most of potential loss of FIT sensitivity due to Hb degradation. Another option would be use of increasingly available point-of-care rather than remote laboratory analysis for Hb measurements, thereby avoiding unnecessary remote transportation. In a recent head-to-head comparison of nine different FITs, diagnostic performance of point-of-care measurements was no worse than diagnostic performance of laboratory-based tests.18 Nevertheless, Hb stability should be specifically investigated separately for the specific FIT being employed, given likely but essentially unknown differences in buffers used by different manufacturers.

In no case, concerns about Hb stability should be used as an argument not to make use of the potential of FIT-based screening offers in reducing CRC incidence and mortality. Even if Hb degradation would lead to a moderate loss in sensitivity under unusually warm conditions, a less than perfect FIT or a FIT postponed to a cooler day would still be superior to abstaining from screening due to stability concerns. Further research should, however, focus on ways to ensure maximum possible diagnostic accuracy under any environmental conditions, or to even enhance performance, eg, by combining FITs with other promising early detection markers.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

Sensitivity and specificity of FIT for AN according to FIT cutoff and mean of daily maximum temperatures during sample travel

| FIT cutoff (µg/g) | Maximum temperature (°C) | Sensitivity (N=267 with AN)

|

Specificity (N=2,603 without AN)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP/NAN | % (95% CI) | TN/Nno AN | % (95% CI) | ||

| 10 | <10 | 46/87 | 52.9 (41.9–63.7) | 707/805 | 87.8 (85.4–90.0) |

| 10–19 | 55/100 | 55.0 (44.7–65.0) | 886/1019 | 86.9 (84.7–89.0) | |

| 20–24 | 30/56 | 53.6 (39.7–67.0) | 436/484 | 90.1 (87.1–92.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 14/24 | 58.3 (36.6–77.9) | 252/295 | 85.4 (80.9–89.2) | |

|

| |||||

| 15 | <10 | 38/87 | 43.7 (33.1–54.7) | 750/805 | 93.2 (91.2–94.8) |

| 10–19 | 47/100 | 47.0 (36.9–57.2) | 938/1019 | 92.1 (90.2–93.6) | |

| 20–24 | 23/56 | 41.1 (28.1–55.0) | 450/484 | 93.0 (90.3–95.1) | |

| ≥ 25 | 10/24 | 41.7 (22.1–63.4) | 273/295 | 92.5 (88.9–95.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 17 | <10 | 38/87 | 43.7 (33.1–54.7) | 759/805 | 94.3 (92.5–95.8) |

| 10–19 | 46/100 | 46.0 (36.0–56.3) | 949/1019 | 93.1 (91.4–94.6) | |

| 20–24 | 23/56 | 41.1 (28.1–55.0) | 451/484 | 93.2 (90.6–95.3) | |

| ≥ 25 | 9/24 | 37.5 (18.8–59.4) | 276/295 | 93.6 (90.1–96.1) | |

|

| |||||

| 20 | <10 | 35/87 | 40.2 (29.9–51.3) | 767/805 | 95.3 (93.6–96.6) |

| 10–19 | 44/100 | 44.0 (34.1–54.3) | 963/1019 | 94.5 (92.9–95.8) | |

| 20–24 | 22/56 | 39.3 (26.5–53.2) | 459/484 | 94.8 (92.5–96.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 7/24 | 29.2 (12.6–51.1) | 277/295 | 93.9 (90.5–96.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 25 | <10 | 33/87 | 37.9 (27.7–49.0) | 775/805 | 96.3 (94.7–97.5) |

| 10–19 | 41/100 | 41.0 (31.3–51.3) | 978/1019 | 96.0 (94.6–97.1) | |

| 20–24 | 19/56 | 33.9 (21.8–47.8) | 465/484 | 96.1 (93.9–97.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 7/24 | 29.2 (12.6–51.1) | 282/295 | 95.6 (92.6–97.6) | |

Note: Italic text represents results for the cutoff recommended by the manufacturer.

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); FIT, fecal immunochemical test; NAN, number of participants with advanced neoplasm; Nno AN, number of participants without advanced neoplasm; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent cooperation of gastroenterology practices and clinics in patient recruitment and of Labor Limbach in sample collection. We gratefully acknowledge Dr Katja Butterbach, Dr Katarina Cuk, and Ulrike Schlesselmann for their excellent work in laboratory preparation of blood samples. We also gratefully acknowledge Isabel Lerch, Susanne Köhler, Dr Utz Benscheid, Jason Hochhaus, and Maria Kuschel for their contribution in data collection, monitoring, and documentation. The BliTz study was partly funded by a grant from the German Research Council (DFG, Grant No BR1704/16-1). The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, monitoring, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that they received no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):37–53. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):1016–1030. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park DI, Ryu S, Kim YH, et al. Comparison of guaiac-based and quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood testing in a population at average risk undergoing colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):2017–2025. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner H, Tao S. Superior diagnostic performance of faecal immunochemical tests for haemoglobin in a head-to-head comparison with guaiac based faecal occult blood test among 2235 participants of screening colonoscopy. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(14):3049–3054. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro JA, Bobo JK, Church TR, et al. A comparison of fecal immunochemical and high-sensitivity guaiac tests for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1728–1735. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grazzini G, Ventura L, Zappa M, et al. Influence of seasonal variations in ambient temperatures on performance of immunochemical faecal occult blood test for colorectal cancer screening: observational study from the Florence district. Gut. 2010;59(11):1511–1515. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rossum LG, van Oijen MG. Different seasons with decreased performance of immunochemical faecal occult blood tests in colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2011;60(9):1303–1304. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223412. author reply 1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha JM, Lee JI, Joo KR, et al. Performance of the fecal immunochemical test is not decreased by high ambient temperature in the rapid return system. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(8):2178–2183. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2139-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Roon AH, Hol L, van Vuuren AJ, et al. Are fecal immunochemical test characteristics influenced by sample return time? A population-based colorectal cancer screening trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(1):99–107. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zorzi M, Baracco S, Fedato C. Limited effect of summer warming on the sensitivity of colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2012;61(1):162. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.233023. author reply 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symonds EL, Osborne JM, Cole SR, Bampton PA, Fraser RJ, Young GP. Factors affecting faecal immunochemical test positive rates: demographic, pathological, behavioural and environmental variables. J Med Screen. 2015;22(4):187–193. doi: 10.1177/0969141315584783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doubeni CA, Jensen CD, Fedewa SA, et al. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colon cancer screening: variable performance with ambient temperature. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):672–681. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.160060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catomeris P, Baxter NN, Boss SC, et al. Effect of temperature and time on fecal hemoglobin stability in 5 fecal immunochemical test methods and one guaiac method. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;142(1):75–82. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0294-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Werner S, Brenner H. Fresh vs frozen samples and ambient temperature have little effect on detection of colorectal cancer or adenomas by a fecal immunochemical test in a colorectal cancer screening cohort in Germany. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(10):1547–1556e1545. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown LF, Fraser CG. Effect of delay in sampling on haemoglobin determined by faecal immunochemical tests. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008;45(Pt 6):604–605. doi: 10.1258/acb.2008.008024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hundt S, Haug U, Brenner H. Comparative evaluation of immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal adenoma detection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):162–169. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner H, Tao S, Haug U. Low-dose aspirin use and performance of immunochemical fecal occult blood tests. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(22):2513–2520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gies A, Cuk K, Schrotz-King P, Brenner H. Direct comparison of diagnostic performance of 9 quantitative fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(1):93–104. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niedermaier T, Weigl K, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Diagnostic performance of one-off flexible sigmoidoscopy with fecal immunochemical testing in a large screening population. Epidemiology. 2018;29(3):397–406. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst) DWD Climate Data Center (CDC): Historische tägliche Stationsbeobachtungen (Temperatur, Druck, Niederschlag, Sonnenscheindauer, etc.) für Deutschland, Version v005. 2017. [Accessed November 13, 2017]. Available from: ftp://ftp-cdc.dwd.de/pub/CDC/observations_germany/climate/daily/kl/historical/

- 21.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing [computer program] Vienna, Austria: R Core Team; 2016. [Accessed August 8, 2018]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Package “binom” - Binomial Confidence Intervals For Several Parameterizations [computer program] [Accessed August 8, 2018];Version. 1:1–02014. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/binom/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sentinel Diagnostics Fob Gold - the universal system for fecal occult blood testing (FIT) [Accessed January 15, 2018]. Available from: http://www.sentinel.it/en/fob-gold-line/fobgold.aspx.

- 24.Morikawa T, Kato J, Yamaji Y, Wada R, Mitsushima T, Shiratori Y. A comparison of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test and total colonoscopy in the asymptomatic population. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiu HM, Lee YC, Tu CH, et al. Association between early stage colon neoplasms and false-negative results from the fecal immunochemical test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):832–838.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong MC, Ching JY, Chan VC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a qualitative fecal immunochemical test varies with location of neoplasia but not number of specimens. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(8):1472–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr PR, Holleczek B, Stegmaier C, Brenner H, Hoffmeister M. Meat intake and risk of colorectal polyps: results from a large population-based screening study in Germany. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1453–1461. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.148304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang LC, Shun CT, Hsu WF, et al. Fecal immunochemical test detects sessile serrated adenomas and polyps with a low level of sensitivity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(6):872–879.e871. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heigh RI, Yab TC, Taylor WR, et al. Detection of colorectal serrated polyps by stool DNA testing: comparison with fecal immunochemical testing for occult blood (FIT) PloS one. 2014;9(1):e85659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrank WH, Patrick AR, Brookhart MA. Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):546–550. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1609-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Sensitivity and specificity of FIT for AN according to FIT cutoff and mean of daily maximum temperatures during sample travel

| FIT cutoff (µg/g) | Maximum temperature (°C) | Sensitivity (N=267 with AN)

|

Specificity (N=2,603 without AN)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP/NAN | % (95% CI) | TN/Nno AN | % (95% CI) | ||

| 10 | <10 | 46/87 | 52.9 (41.9–63.7) | 707/805 | 87.8 (85.4–90.0) |

| 10–19 | 55/100 | 55.0 (44.7–65.0) | 886/1019 | 86.9 (84.7–89.0) | |

| 20–24 | 30/56 | 53.6 (39.7–67.0) | 436/484 | 90.1 (87.1–92.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 14/24 | 58.3 (36.6–77.9) | 252/295 | 85.4 (80.9–89.2) | |

|

| |||||

| 15 | <10 | 38/87 | 43.7 (33.1–54.7) | 750/805 | 93.2 (91.2–94.8) |

| 10–19 | 47/100 | 47.0 (36.9–57.2) | 938/1019 | 92.1 (90.2–93.6) | |

| 20–24 | 23/56 | 41.1 (28.1–55.0) | 450/484 | 93.0 (90.3–95.1) | |

| ≥ 25 | 10/24 | 41.7 (22.1–63.4) | 273/295 | 92.5 (88.9–95.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 17 | <10 | 38/87 | 43.7 (33.1–54.7) | 759/805 | 94.3 (92.5–95.8) |

| 10–19 | 46/100 | 46.0 (36.0–56.3) | 949/1019 | 93.1 (91.4–94.6) | |

| 20–24 | 23/56 | 41.1 (28.1–55.0) | 451/484 | 93.2 (90.6–95.3) | |

| ≥ 25 | 9/24 | 37.5 (18.8–59.4) | 276/295 | 93.6 (90.1–96.1) | |

|

| |||||

| 20 | <10 | 35/87 | 40.2 (29.9–51.3) | 767/805 | 95.3 (93.6–96.6) |

| 10–19 | 44/100 | 44.0 (34.1–54.3) | 963/1019 | 94.5 (92.9–95.8) | |

| 20–24 | 22/56 | 39.3 (26.5–53.2) | 459/484 | 94.8 (92.5–96.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 7/24 | 29.2 (12.6–51.1) | 277/295 | 93.9 (90.5–96.3) | |

|

| |||||

| 25 | <10 | 33/87 | 37.9 (27.7–49.0) | 775/805 | 96.3 (94.7–97.5) |

| 10–19 | 41/100 | 41.0 (31.3–51.3) | 978/1019 | 96.0 (94.6–97.1) | |

| 20–24 | 19/56 | 33.9 (21.8–47.8) | 465/484 | 96.1 (93.9–97.6) | |

| ≥ 25 | 7/24 | 29.2 (12.6–51.1) | 282/295 | 95.6 (92.6–97.6) | |

Note: Italic text represents results for the cutoff recommended by the manufacturer.

Abbreviations: AN, advanced neoplasia (colorectal cancer or advanced adenoma); FIT, fecal immunochemical test; NAN, number of participants with advanced neoplasm; Nno AN, number of participants without advanced neoplasm; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; µg/g, microgram hemoglobin per gram of stool.