Abstract

Culturally relevant health promotion is an opportunity to reduce health inequities in diseases with modifiable risks, such as cancer. Alaska Native people bear a disproportionate cancer burden, and Alaska’s rural tribal health workers consequently requested cancer education accessible online. In response, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium cancer education team sought to create a framework for culturally relevant online learning to inform the creation of distance-delivered cancer education. Guided by the principles of community-based participatory action research and grounded in empowerment theory, the project team conducted a focus group with 10 Alaska Native education experts, 12 culturally diverse key informant interviews, a key stakeholder survey of 62 Alaska Native tribal health workers and their instructors/supervisors, and a literature review on distance-delivered education with Alaska Native or American Indian people. Qualitative findings were analyzed in Atlas.ti, with common themes presented in this article as a framework for culturally relevant online education. This proposed framework includes four principles: collaborative development, interactive content delivery, contextualizing learning, and creating connection. As an Alaskan tribal health worker shared “we’re all in this together. All about conversations, relationships. Always learn from you/with you, together what we know and understand from the center of our experience, our ways of knowing, being, caring.” The proposed framework has been applied to support cancer education and promote cancer control with Alaska Native people and has motivated health behavior change to reduce cancer risk. This framework may be adaptable to other populations to guide effective and culturally relevant online interventions.

Keywords: Community-based participatory action research, Community health workers, Alaska Native, Health disparities, Program planning, Online learning, Health promotion

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the USA [1]. In 2015, about a quarter of all deaths in the USA were due to cancer (22%) [1]. However, physical activity, cancer screenings, tobacco, and diet are modifiable factors that could alleviate cancer-related suffering and early death [2].

Ethnic minorities and poorer populations disproportionately suffer from cancer, including higher incidences, worse outcomes, and a higher prevalence of risk factors [3]. However, health promotion strategies tailored to minority populations are thought to be more effective, appropriate, and more likely to lead to health behavior change [4]. This paper describes research on, and presents a framework for, culturally relevant online cancer education developed with, and for, Alaska’s tribal health workers.

Alaska Native people suffered a cancer mortality rate approximately 34% higher than US Whites and 47% higher than non-Native Alaskans in 2008–2011 [5]. The leading cancer incidence sites among Alaska Native people were lung, colorectal, and breast; all of which have modifiable risk factors [6]. The most recent data available, aggregated where possible to improve stability of estimates, revels continuing disparities. In 2012–2016, 38.5% of Alaska Native adults reported current smoking (compared with 17.2% of Alaska White adults and 17.1% of US adults in 2016) [7, 8]. In 2012–2016, 35.4% of Alaska Native adults reported being obese, compared to 27.8% of Alaska Whites, and 29.9% of the US population in 2016 [7, 8]. In 2011–2015, 9.0% of Alaska Native people reported eating at least three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruits each day, significantly lower than the 12.6% of White Alaskans who met this standard [7].

Background

Primary medical care in rural Alaska, including promotion of healthy eating, physical activity, tobacco cessation, and cancer screenings, is largely provided by Community Health Aides/Practitioners (CHA/Ps). CHA/Ps work as part of the well-established Community Health Aide Program (CHAP), and operate within the guidelines of the Alaska Community Health Aide/Practitioner Manual, but are often the sole healthcare providers in their 178 rural communities [9]. CHA/Ps are selected by their communities and complete four 3- to 4-week training sessions, a clinical skills preceptorship, and an examination, as well as complete continuing education to maintain certification [9]. While cancer is the leading cause of death in Alaska, only two of the 588.5 h of basic training (0.3%) are dedicated to cancer [9, 10].

Due to the impact of cancer within their communities, CHA/Ps requested additional information about cancer, and in response, the cancer education team at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium taught in-person cancer and wellness courses since 2002 [11, 12]. However, Alaska’s geographic and recent financial challenges have restricted the amount of in-person education that can be made available to CHA/Ps, and the transition of CHAP clinics to high-speed Internet has provided an opportunity to engage CHA/Ps in online education.

Teaching/learning methods—ways of knowing—that resonate with Alaska’s CHA/Ps have been previously incorporated into in-person cancer education [12]. However, the transition to an online format raised questions on how to create culturally relevant learning experiences online. This study has been conducted in partnership with Alaska’s CHA/Ps to understand how CHA/Ps ways of knowing could be interpreted online to develop a framework for culturally relevant education.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

This exploration of culturally relevant online learning was guided by the principles of community-based participatory action research (CBPAR) that honors Indigenous ways of knowing and is grounded in empowerment theory. CBPAR is a partnership between communities and academics/researchers that focuses on locally relevant issues, builds on community strengths, and realizes social change to reduce inequities [13]. This framework guided the collaboration of the project team, CHA/Ps, and CHA/P supervisors and instructors. In alignment with the CBPAR principles to “promote co-learning and capacity building” and conduct work in “collaborative, equitable partnerships,” the project team collaborated with CHA/Ps throughout the process [14]. Ways of knowing identified by Alaska’s CHA/Ps, such as storytelling, humor, expressive arts, and building relationships, echo Indigenous ways of knowing, including incorporating affective and subjective elements, and learning within the context of relationships, observations, and experiences [12, 15].

Empowerment theories are both a foundation of CBPAR and a natural extension of the ongoing CBPAR with Alaska’s CHA/Ps. Paulo Freire’s Popular Education is a theoretical root of CBPAR and advocates for empowering education that leads to social transformation—an idea identified as an effective health education strategy [13]. Empowerment-oriented approaches are also fundamental in working with Indigenous communities. Historical trauma linked to the colonization of Indigenous peoples has disrupted traditional food systems and cultural practices that facilitated physical activity, healthy weight, and limited tobacco use, and is linked by some Indigenous researchers to contemporary cancer disparities [16]. Acknowledging historical trauma and its impacts, CBPAR theorists advocate that work with Indigenous communities focus on self-determination and empowerment [17], an approach actualized by this project’s focus on cultural relevancy and cultural strength. Intertwined with self-determination, empowerment is a contextual, participatory process that advances social justice and redistributes power to increase control [18]. Empowerment-oriented approaches are designed to:

“…enhance wellness while they also aim to ameliorate problems, provide opportunities for participants to develop knowledge and skills, and engage professionals as collaborators instead of as authoritative experts.” [18]

Empowerment theory is a framework that guides these approaches, and CBPAR “exemplifies empowering processes,” including working with the community and building capacity [19]. CHA/Ps are uniquely situated to empower health behavior change due to their existing relationships and trust within their communities, their role as the medical providers in rural Alaska, and their centrality within community-level health and wellness networks.

Focus Group of Alaska Native Education Experts

A focus group was convened to examine experts’ perceptions of culturally relevant pedagogy, culturally respectful training, the role of cultural values, and any additional ways to support CHA/P learning. Potential focus group participants were identified as experts in education with, and for, Alaska Native people. Additional participants were recruited through snowball sampling. One in-person 1-h focus group was organized around participants’ schedules in December 2014, and was attended by all invited individuals. Project team members facilitated/participated in the discussion at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Participants summarized key themes during the meeting, and a summary was shared with participants for affirmation.

Survey of Key Stakeholders

A 16-item survey of Alaska’s CHA/Ps and CHA/P leadership was developed by the CHAP cancer education project team in collaboration with potential survey participants. The survey was administered online via eSurveysPro in January 2015 to CHA/Ps, CHA/P supervisors and instructors, and other tribal community health workers in Alaska. The survey included questions on distance-delivered cancer education, such as respondents’ capacity and comfort with online learning, what culturally relevant online learning would include, and what activities and/or format support learning in an online environment. No master contact list of the estimated 378 Alaska CHA/Ps exists, and consequently, the survey was disseminated by email to CHAP training center coordinators, CHAP directors, the CHAP academic liaison, the CHA association president, and directly to CHA/Ps who had previously participated in cancer education courses, with all recipients invited to share the link to additional CHA/Ps (personal communication with Alaska CHAP, 2015; [20].

Key Informant Interviews

Interviews with key informants selected to represent the geographic and cultural diversity of the CHA/Ps in Alaska investigated experiences with online education, perceptions of culturally respectful online cancer education, information sharing in their communities, and demographic information. Each potential key informant was contacted initially through email, with follow-up via telephone. Individuals provided verbal consent and participated in semi-structured conversations facilitated by an interview guide developed by the CHAP cancer education project team and CHA/Ps. The interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed in Atlas.ti by the project team, with quantitative data summarized in Microsoft Excel.

Literature Review

Literature searches of online education with Alaska Native or American Indian people were conducted in March–April 2015 on JSTOR, Web of Science and PubMed. The searches used the keywords: education, and distance or online or internet, and Alaska Native or American Indian. After a scan of titles, relevant search results were downloaded into Mendeley. Duplicates were deleted, and additional irrelevant results were eliminated after an abstract review.

Institutional Review

This research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Alaska Area Institutional Review Board, the University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board, and the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) Executive Committee. Additionally, this manuscript was reviewed and approved by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium Health Research Review Committee and the SCF Executive Committee.

Results

Focus Group Findings

Ten Alaska Native education experts were identified, and all participated in the focus group, including eight women and six Alaska Native or American Indian individuals. Participants identified culturally respectful learning as focusing on:

Building relationships/interactions, including through collaboration, synchronous meetings, communication portals, etc., to express that individuals are valued for who they are, are respected for where they are at in terms of understanding, and are invited to learn. “We’re all in this together. All about conversations, relationships. Always learn from you/with you, together what we know and understand from the center of our experience, our ways of knowing, being, caring.”

Including information relevant to learners, including connecting content “to larger cause, bigger picture.” Individuals talked about culturally relevant content as including Alaska-specific information, stories, pictures, and statistics.

Incorporating multiple modalities of learning, such as games, interactives, stories, etc.

Incorporating visuals: “More pictures, less words.”

Respecting traditional values by incorporating humor, storytelling, and honoring elders and ancestors.

Survey Findings

A total of 62 completed surveys were received, with 43 submitted by Alaska CHA/Ps, and others completed by CHA/P instructors/supervisors and other Alaska community health workers. In response to the prompt “An online course that is respectful of my culture would include…,” respondents shared the following common themes:

Relevant and locally specific statistics, pictures, examples, and stories, such as “examples from my culture that are relevant to materials and learning expectations.”

Information on traditional/alternative healing practices, such as those shared by “traditional or tribal doctors.”

Being respectful of individuals from diverse cultures and allowing learners to share who they are in a supportive environment: “A mutual respect and regard for various cultures. To be sensitive to someone’s beliefs, values and their way of coping. To be concerned enough to really listen without so much input if not desired.”

Respondents were also asked “What activities and/or format make online learning helpful, interesting and fun?” Individuals’ responses included the following common themes:

Interactivity, such as quizzes, or “games as learning tools or test prep.”

Visuals, including videos and pictures: “I am also very visual. Too much text without visual aids make my brain lose interest and become tired. Animation and watching videos helps a lot too.”

Connecting in real-time with other individuals involved in the learning experience to develop relationships through live chat or a live video chat.

Survey findings have been published more extensively in the Journal of Cancer Education [20].

Key Informant Interview Findings

Twenty-four individuals were selected as potential interview participants, chosen to represent the geographic and cultural diversity of CHA/Ps in rural Alaska. More than twice the target number of key informants were selected, anticipating attrition. Each potential key informant was contacted three to five times via email and multiple times via telephone. All potential key informants were interested in participating in an interview, but 12 were unable to find time for the conversation, citing busy clinic schedules and/or subsistence activities. Twelve telephone interviews were conducted February–April 2015. All interviewees were female and included four CHA/P supervisors and instructors, one CHAP program manager, and seven CHA/Ps. Respondents could choose multiple ethnicities; three identified as Caucasian and ten identified as Alaska Native, including Yup’ik, Inupiaq, Siberian Yupik, Athabascan, Unangan, and “Alaska Native.” Respondents were from communities throughout Alaska, including the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands, Arctic Slope, Bristol Bay, Interior, Northwest Arctic, and Norton Sound regions. Due to uneven attrition, no men or respondents from southeast Alaska participated. Ages ranged from 15 to 64, with five under age 33, and six age 48 and older.

Common themes on what culturally respectful online cancer education would look like were:

True personal stories of local individuals: “I really like the personal stories – it makes it real, it makes it personal and in their own words. So that means a lot.” Respondents also noted that hearing/seeing stories were a way to connect with other individuals, even if the online nature of the course did not allow for directly building relationships with others: “we’re all connected – the people taking the course are from all over Alaska and it’s good to see them.” Respondents noted that digital stories created during in-person cancer education courses helped learners understand content both cognitively and affectively and were relevant to include: “I know the digital stories – they are about our people. Those stories, they were pretty intense, but it would definitely be good to have digital stories in an online course.”

-

Pictures/visuals, particularly Alaska-specific images and videos relevant to content:

“The more of that the better (color and things), because if you think about it we’re really – a lot of us are visual people so we have to see and hear - so we’re visual. I think that’s very important because we have to visualize what’s being taught.” Interviewees also shared that too much text was a barrier to learning: “things don’t catch my attention and I would have to read a paragraph over and over and things just don’t stick if I have to read so much to learn.” However, simplifying text to be “very basic and straight to the point” could help make reading more understandable.

Learning through relationships. Either through hearing and seeing individuals tell their stories, or being part of a supportive group to “have the opportunity to share ideas more,” respondents discussed the importance of connecting with others to learn.

Respondents shared their appreciation for being a part of the education development, and wanted continued collaboration on the development of the online education, whether involving them personally: “We could maybe get a few people in a room and just have a brainstorming session,” or reaching out to other people to ask what was relevant to their learning: “you could ask them – the people that are going to be taking the class,”

Interactives/games were described as enhancing learning and reinforcing content: “What I kind of like is the definitions and like cross-matching and things like that. Maybe we could have cancer jeopardy. I don’t really play much games on the computer, but anything to do with trivia, I like that.”

Acknowledging and respecting learners’ cultural differences and diversity among and between Alaska Native cultures: “Just to understand that there are differences, real differences in language and culture and tribes.” Survey respondents shared that acknowledging this diversity could be actualized as incorporating stories and examples from throughout Alaska.

Additionally, 25 survey respondents offered to be a resource to help guide the collaborative development of the proposed culturally relevant cancer education and became a community advisory group for the development of the project.

Literature Review Findings

The literature review on distance-delivered education with Alaska Native or American Indian people produced an initial total of 59 articles. A scan of titles eliminated 42 results as irrelevant, and an additional four results as duplicates. The remaining 13 articles were exported into Mendeley, and an abstract review eliminated six results as irrelevant. The resulting seven articles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of literature review on distance-delivered education with Alaska Native and/or American Indian learners

| Author, year | Study design | Findings on culturally relevant learning |

|---|---|---|

| Case et al. 2009 [21] | Analyzed message board postings among 45 Caucasian, African-American, and American Indian/Alaska Native participants who had enrolled in an online diabetes self-management program | Authors concluded that because there were few differences in the ways that Caucasian and non-Caucasian learners used message boards that the technology may be flexible enough to accommodate different racial groups. |

| Chavez et al. 2012 [22] | Interviewed 50 Native American, Hispano, and Mestizo American students enrolled in online college courses about their ways of learning and knowing | Acknowledging the purpose of learning and connecting learning to the broader community and world. Contextualizing learning within previous experiences and students’ unique contexts. Facilitating learning in relationship with peers and supportive instructors. Giving time for internal processing through asynchronous discussions. Learning a concept first through stories/examples following by narrowing to specifics. |

| Cueva et al. 2014 [23] | 20 interviews of Alaska CHA/P reactions to an interactive CD-ROM on colorectal cancer. | Developed in partnership with CHA/Ps, learning within community through humor, expressive arts, and stories. Content honored traditional values such as family, relationships, and a connection to the land. |

| Doorenbos et al. 2011 [24] | Describes efforts to establish a telehealth network to deliver post-cancer-diagnosis services and education in Alaska and Washington. | Community-based participatory approach with respected tribal members. Emphasized understanding tribal sovereignty and governance. Program success attributed to cultural liaisons and coordinators. |

| Locatis et al. 2009 [25] | Describes the expansion of a distance learning program (two-way interactive video) to Kotzebue, Alaska | Noted that content had not been tailored to learners, however, also described importance of understanding local context and coordinating with local individuals. |

| Galloway 2007 [26] | Describes efforts to create educational networks to create culturally reinforcing, professional health education | Team-based approach, connection to community |

| Hites et al. 2012 [27] | Adapted online content of 20 modules to better serve American Indian learners. | Starting with big picture then integrating details, visual/perceptual instruction, time for self-reflection (vs. impromptu discussion), cooperation and group work/discussion. |

The small number of articles on distance-delivered educational interventions designed with, and/or for, American Indian and/or Alaska Native people illuminates a lack of research in this area. Common themes included the following:

Collaborative and community-based approaches to developing content

Locally relevant content

Building relationships to facilitate learning

Learning through stories, interactivity, and visuals

Discussion

The descriptions of culturally relevant online cancer education address a need to identify a framework for specific health promotion interventions that promote health equity. This multi-faceted study conducted with Alaska’s CHA/Ps reveals the following shared principles for culturally relevant online cancer education:

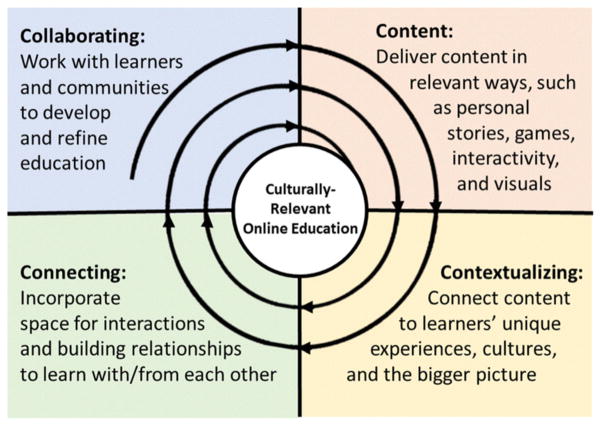

Collaborating to develop content: working with the community to tailor the educational intervention, and understand how facets of the education are interpreted and valued by the population of potential learners.

Creating content: incorporating ways of learning that resonate with learners. Findings indicate that culturally relevant online cancer education with Alaska Native people would include content delivery through true personal stories, visuals, games, and interactivity.

Contextualizing: connecting content to learners’ unique cultures, communities and regions; including by incorporating local information, artwork, pictures, stories, visuals, and relevant “big picture” motivations to support learning.

Connecting: incorporating space for interactions and relationship building to learn with/from peers and instructors, whether through synchronous sessions or including asynchronous personal stories from the population of potential learners.

These guiding principles comprise a framework for culturally relevant online cancer education, which has been summarized as Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A proposed framework for culturally relevant online education

In this figure, arrows indicate that the process is iterative and ongoing.

While few published articles present principles for culturally relevant online learning with any population, two culturally relevant online education strategies resonate with findings from this study. Sanchez and Gunawardena offered guidelines for distance-delivered education with Hispanic/Latino adult learners that included engaging in collaborative activities, providing space to build relationships with other students and the instructor, allowing students to process and reflect by incorporating asynchronous message boards, and emphasizing concrete learning through experimentation/activities [28]. This article supports the findings identified in this research, although the recommendations for content delivery methods are slightly different, perhaps reflecting the unique needs of the authors’ learners.

Grounded in distance learning for indigenous Australians, McLoughlin has proposed features of web-based education that promote equity [29]. McLoughlin emphasizes cultural maintenance (incorporating values, learning styles, etc.), while facilitating ownership of learning, communities of practice, and multiple perspectives that recognize diversity among learners. McLoughlin’s work resonates with the framework presented here, with similarities between “cultural maintenance” and “content.” However, the framework presented here takes culturally relevant online learning a step further by emphasizing not just content delivery methods, but connections between learners and course development, implementation, and continual refinement of the educational initiative.

Conclusion

The presented framework for culturally relevant online cancer education addresses a need for principles to guide targeted health education that promotes health equity. Online cancer education modules have been developed in accordance with this framework. These developed modules inspired all learners to share cancer information, either with their patients, families, friends, and communities and motivated 94% of learners to personally engage in cancer risk reduction behaviors such as eating healthier, getting cancer screenings, exercising more, and quitting tobacco [30]. The framework for culturally relevant online education proposed in this manuscript may be adaptable to other populations or topic areas to empower health behavior change and reduce health disparities. Further research is needed to test and refine this framework to examine the impact of each construct independently, and to assess the framework’s effectiveness in different cultural contexts.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of “Distance Education to Engage Alaskan Community Health Aides in Cancer Control,” supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), award R25CA186882. Theoretical understandings and manuscript preparation and submission were supported by NIH grant 3R25CA057711. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH.

References

- 1.CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. FastStats. [Accessed 9 Jun 2017];Deaths Mortal. 2017 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm.

- 2.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Chronic disease overview. 2016 https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/#ref2.

- 3.Crook ED, Peters M. Health disparities in chronic diseases: where the money is. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:266–270. doi: 10.1097/maj.0b013e31816902f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Communication for Behavior Change in the 21st Century: Improving the Health of Diverse Populations. Speaking of health: assessing health communication strategies for diverse populations. National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly JJ, Schade TL, Starkey BM, et al. Cancer in Alaska Native People: 1969–2008: 40-year report. Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, Office of Community Health Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmack AM, Schade TL, Sallison I, et al. Alaska Native Tumor Registry. Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium; 2015. Cancer in Alaska Native people: 1969–2013, the 45 year report. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. [Accessed 16 Jan 2018];Alaska’s Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System - Query Module. http://ibis.dhss.alaska.gov/query/result/BRFSS23/BRFSS_S/X5ADAY.html.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 5 May 2017];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: Prevalence & Trends Data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html.

- 9.Alaska CHAP. [Accessed 5 May 2017];Alaska Community Health Aides - About CHAP. 2017 http://www.akchap.org/html/about-chap.html.

- 10.Lengdorfer Heidi, Topol Rebecca, Raines Richard. Health Analytics Unit of the Alaska Health Analytics and Vital Records Section. 2017. Leading causes of death in Alaska, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cueva M, Lanier AP, Kuhnley R, Dignan M. Cancer education: a catalyst for dialogue and action. IHS Prim Care Provid. 2008;33(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Cueva K. Enhancing cancer education through the arts: building connections with Alaska Native people, cultures and communities. Int J Lifelong Educ. 2012;31:341–357. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen A, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cajete G. Look to the mountain: an ecology of indigenous education. Kivaki Press; Durango: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prussing E. Historical trauma: politics of a conceptual framework. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51:436–458. doi: 10.1177/1363461514531316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez V, Minkler M, Wallerstein N, Spencer M. Community organizing for health and social justice. In: Cohen L, Chavez V, Chehimi S, editors. Prevention is primary: strategies for community well-being. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2010. pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins DD, Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:569–579. doi: 10.1007/BF02506982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:581–599. doi: 10.1007/BF02506983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cueva K, Revels L, Kuhnley R, Cueva M, Lanier A, Dignan M. Co-creating a culturally responsive distance education cancer course with, and for, Alaska’s community health workers: motivations from a survey of key stakeholders. J Cancer Educ. 2015;32:426–431. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0961-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Case S, Jernigan V, Gardner A, et al. Content and frequency of writing on diabetes bulletin boards: Does race make a difference? J Med Internet Res. 2009:11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Chavez AF, Ke F, Herrera FA. Clan, sage, and sky: Indigenous, Hispano, and Mestizo narratives of learning in New Mexico Context. Am Educ Res J. 2012;49:775–806. doi: 10.3102/0002831212441498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cueva M, Dignan M, Lanier A, Kuhnley R. Qualitative evaluation of a colorectal cancer education CD-ROM for Community Health Aides/practitioners in Alaska. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:613–618. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doorenbos AZ, Demiris G, Towle C, et al. Developing the native people for cancer control telehealth network. Telemed J E-Health. 2011;17:30–34. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Locatis C, Gaines C, Liu W-L, Gill M. Extending a blended education program to native American high school students in Alaska. J Vis Commun Med. 2009;32:8–13. doi: 10.1080/17453050902821181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galloway JM. Pathways into health: Health professions education for American Indian and Alaska natives utilizing distance learning, interprofessional education, and cultural integration. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:3–4. doi: 10.1080/13561820701634235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hites LS, Granillo BS, Garrison ER, Cimetta AD, Serafin VJ, Renger RF, Wakelee JF, Burgess JL. Emergency preparedness training of tribal community health representatives. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez I, Gunawardena C. Understanding and supporting the culturally diverse distance learner. In: Gibson CC, editor. Distance learners in higher education. Atwood Publishing; Madison: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLoughlin C. Cultural Maintenance, Ownership, and Multiple Perspectives: features of Web-based delivery to promote equity. J Educ Media. 2000;25(3):229–241. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cueva K, Revels L, Cueva M, Lanier AP, Dignan M, Viswanath K, Fung TT, Geller AC. Culturally-relevant online cancer education modules empower Alaska’s community health aides/practitioners to disseminate cancer information and reduce cancer risk. J Cancer Educ. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]