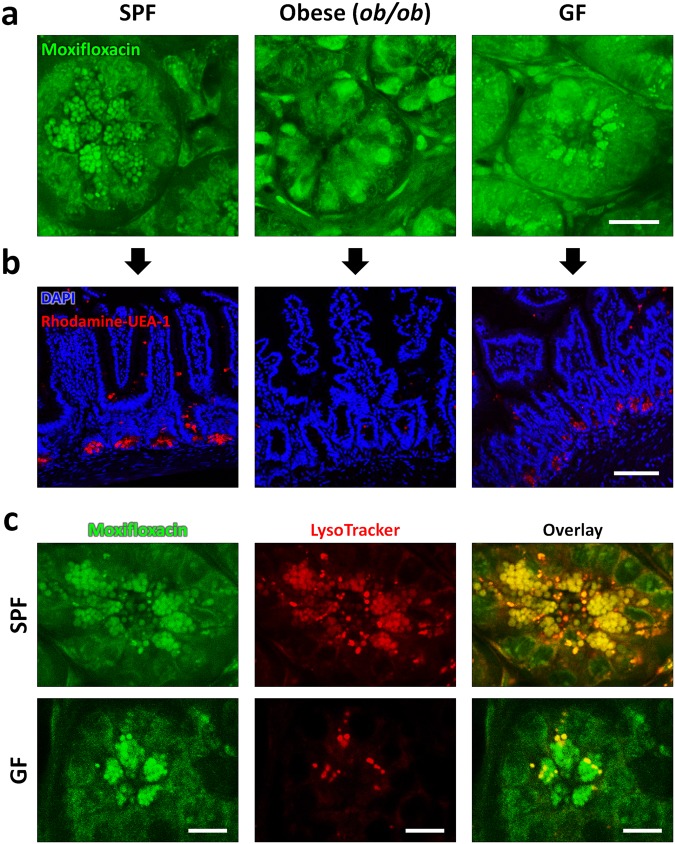

Figure 2.

In vivo Moxifloxacin-based TPM images and ex-vivo fluorescently labeled images of small intestinal crypts in mice under different environmental and metabolic conditions. (a) In vivo moxifloxacin-based TPM images at the base of intestinal crypts in SPF, obese (ob/ob), and GF mice. In wild type SPF mice, Paneth cell granules are clearly visible via moxifloxacin labeling. In obese (ob/ob) mice, Paneth cell granules did not appear at the base of intestinal crypts, but there were some cells expressing moxifloxacin fluorescence in the cytoplasm. In wild type GF mice, Paneth cell granules appeared similarly to those of SPF mice in moxifloxacin-based TPM. (b) Ex vivo fluorescence images of the small intestine sections from SPF, obese (ob/ob), and GF mice. Cell nuclei and Paneth cell granules in the fixed and permeablilized small intestinal sections were stained with DAPI (blue) and rhodamine-UEA-1 (red), respectively. Fluorescence images of the sectioned small intestine tissues showed epithelial linings and Paneth cell granules at the bottom. Paneth cell granules were visible in SPF and GF mice only, and not detected in obese (ob/ob) mice. These fluorescence image results of the sectioned intestinal crypts were consistent with in vivo moxifloxacin-based TPM results. (c) In vivo TPM images of Paneth cell granules in SPF and GF mice with the counterstaining of both moxifloxacin and LytoTracker. TPM images of SPF mice showed that both moxifloxacin and LysoTracker similarly labeled Paneth cell granules. On the other hand, TPM images of GF mice showed that LysoTracker labeled only a portion of moxifloxacin-labeled Paneth cell granules. In this experiment, the number of mice used are as follows; wild type C57BL/6 mice bred in a SPF condition (n = 5), germfree (GF) condition (n = 9), obese (ob/ob) mice (n = 8). Scale bars in (a,b), and (c) are 20 μm, 100 μm, and 10 μm, respectively.