DNA architecture influences genome-editing efficiency

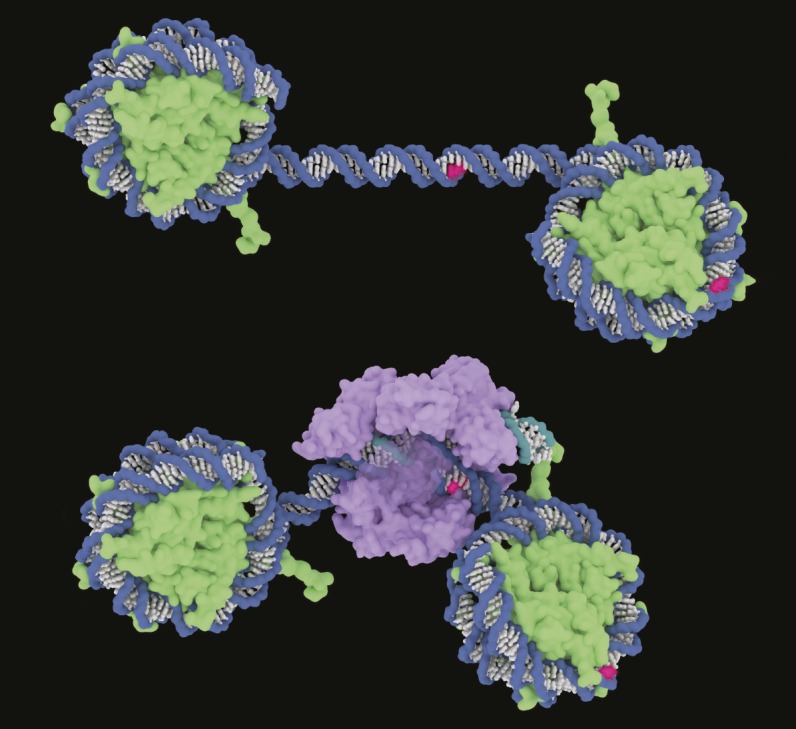

Illustration of Cas9 binding to DNA. Hypothetical PAM sites for Cas9 targets are shown in red; DNA backbones are blue; RNA backbone is teal; DNA and RNA bases are white, except for PAM; histones are green; and Cas9 is purple. Image courtesy of Janet Iwasa (University of Utah, Salt Lake City).

Biochemical experiments have revealed that the enzyme Cas9, isolated from Streptococcus pyogenes and used in the genome-editing approach CRISPR-Cas9, balks at target DNA sequences assembled into nucleosomes—structures in which DNA is wound around protein spools for packaging into chromosomes. However, whether nucleosomes inhibit Cas9 binding and target DNA cleavage in living cells has been unclear. Using real-time analysis, Robert Yarrington et al. (pp. 9351–9358) report that Cas9 cleaves target DNA sequences in two gene-regulating stretches—HO and PHO5 promoters—of the yeast genome more efficiently when the targets are located in nucleosome-depleted rather than nucleosome-bound sites. Experimentally evicting nucleosomes through the insertion of binding sites for a nucleosome-displacing protein restored Cas9 target binding and cleavage to levels comparable to naturally nucleosome-depleted sites. Conversely, increasing nucleosome occupancy through mutation of binding sites for a gene switch at the HO locus reduced Cas9 cleavage, suggesting that nucleosomes inhibit Cas9 cleavage. In contrast, zinc-finger nucleases, also common genome-editing tools, appeared largely indifferent to the presence of nucleosomes at target sites. Thus, the authors suggest, nucleosome position maps might help improve genome-editing efficiency in some applications, including human somatic therapies aimed at editing nondividing cells, in which nucleosome positions are relatively static, and base-editing efforts, in which Cas9 may need to sift through nucleosomes to edit target sequences without cleaving them. — P.N.

Ancient patterns unite halves of mammalian brain

The brain’s left and right hemispheres are connected via the structure known as corpus callosum in placental mammals, or eutherians, and via the structure called anterior commissure in pouched and egg-laying mammals, or marsupials and monotremes. However, whether the pattern of interhemispheric connections in eutherians arose through the evolution of the corpus callosum or instead reflects more ancient principles of mammalian brain organization remains unclear. Rodrigo Suárez et al. (pp. 9622–9627) compared eutherian datasets with patterns of interhemispheric connections in the monotreme duck-billed platypus and the marsupial fat-tailed dunnart. MRI of fixed dunnart and platypus brains revealed that interhemispheric nerve fibers are spatially arranged within the anterior commissure according to the 3D position of cortical areas, resembling patterns previously observed in the corpus callosum of eutherians. Circuit mapping experiments on dunnart brains revealed additional similarities with known features of the eutherian cortical connectome. According to the authors, the findings provide a framework for future studies on the evolution of vertebrate brain circuits. — J.W.

Intergenerational trends in status mobility

The concept of the United States as a land of opportunity is based on the ideal of children attaining a higher socioeconomic status than parents, and having an equal opportunity to rise or fall to any status, irrespective of origins. Metrics of social mobility, such as intergenerational persistence, describe how closely the outcomes of succeeding generations depend on their origins. Michael Hout (pp. 9527–9532) analyzed intergenerational occupational data from more than 20,000 people surveyed between 1994 and 2016. Plotting the socioeconomic index of adults and their parents, the author found that an increase in parents’ status by one point was paralleled by an increase of one-half point in offsprings’ median status, suggesting strong intergenerational persistence. Further, the author found that intergenerational persistence did not significantly change over the years studied, and that overall mobility declined over the same time period. Fewer people born in the 1980s were upwardly mobile than those born in the 1940s, a finding the author attributes to changing economic conditions in which the two generations entered the workforce. According to the author, the slowing of status mobility accentuates inequalities of opportunity in the United States. — P.G.

Phylogenetic framework to assess age of latent HIV reservoirs

The ability of HIV to persist in latent reservoirs is a major barrier to finding a cure, but reconstructing viral reservoir dynamics is challenging. Bradley Jones et al. (pp. E8958–E8967) developed a phylogenetic framework to assess the integration dates of latent HIV lineages within hosts. The authors used plasma HIV RNA sequences sampled before treatment to reconstruct HIV’s within-host evolutionary history, and this information was then used to infer the ages of latent HIV sequences. The authors used the phylogenetic framework to reconstruct HIV sequence ages from a wide variety of within-host datasets, and reconstructed the integration dates of latent HIV sequences sampled from two chronically HIV-infected individuals up to 10 years after the initiation of suppressive therapy. The authors identified and dated reservoir sequences in multiple within-host lineages, with the oldest integration dates occurring up to 21 years before sampling. Genetic bottleneck events, typical of within-host HIV evolution, were also recorded in the reservoir, and sequences from a viremia blip on suppressive therapy suggested that this event was due to spontaneous in vivo reactivation of several ancestral HIV lineages. According to the authors, latent HIV reservoirs can serve as within-host HIV evolutionary archives, and the phylogenetic framework could provide insights into the reservoir dynamics and persistence of HIV. — S.R.