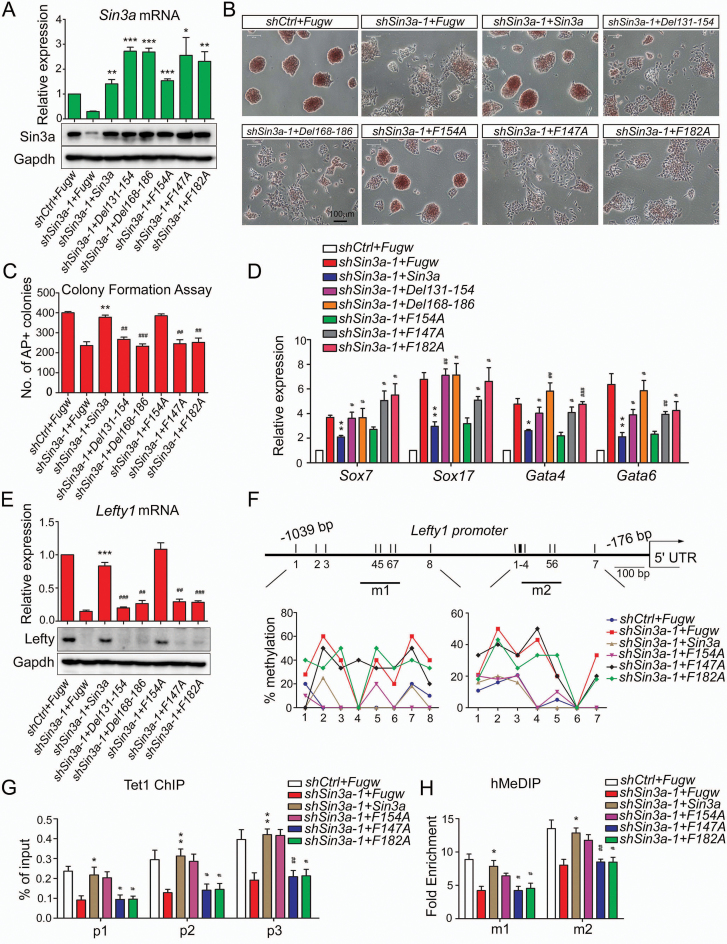

Figure 5.

Sin3a–Tet1 protein interaction is required for Sin3a to maintain ESC pluripotency. (A) RT-qPCR and western blot analyses of ectopic expression of wild-type Sin3a and its mutants (Del131–154, Del168–186, F154A, F147A and F182A).The shSin3a-1-treated ESCs were co-infected with virus of Fugw, wild-type Sin3a or its mutants under self-renewing conditions. Wild-type Sin3a and all the mutants we used here were introduced as nonsense mutations against shSin3a-1 target. (B–D) The effects of expressing ectopic wild-type Sin3a or its mutants described in (A) on Sin3a knockdown phenotype. AP staining (B), colony formation assay (C) and RT-qPCR analysis of several early differentiation markers (D) were performed under self-renewing conditions. (E) The effects of ectopic expression of wild-type Sin3a and its mutants on the expression of Lefty1 in shSin3a-1 ESCs. (F–H) The effects of ectopic expression of wild-type Sin3a and its mutants (F154A, F147A and F182A) on CpG methylation levels (F), Tet1 occupancy (G) and 5hmC level changes (H) at the Lefty1 promoter in shSin3a-1 ESCs. The fold enrichments in (H) are relative to IgG controls after normalizing to the input. The shSin3a-1-treated ESCs that were co-infected with Fugw virus were used as control. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 versus the control; #P< 0.05, ##P< 0.01, ###P< 0.001 versus the Sin3a-overexpressed shSin3a-1 group. Student's t-test (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3).