Abstract

Despite its natural abundance and widespread use as food, paint additive, and in bone implants, no specific biological function of titanium is known in the human body. High concentrations of Ti(IV) could result in cellular toxicity, however, the absence of Ti toxicity in the blood of patients with titanium bone implants indicates the presence of one or more biological mechanisms to mitigate toxicity. Similar to Fe(III), Ti(IV) in blood binds to the iron transport protein serum transferrin (sTf)1, which gives credence to the possibility of its cellular uptake mechanism by transferrin-directed endocytosis. However, once inside the cell, how sTf bound Ti(IV) is released into the cytoplasm, utilized, or stored remain largely unknown. To explain the molecular mechanisms involved in Ti use in cells we have drawn parallels with those for Fe(III). Based on its chemical similarities with Fe(III), we compare the biological coordination chemistry of Fe(III) and Ti(IV) and hypothesize that Ti(IV) can bind to similar intracellular biomolecules. The comparable ligand affinity profiles suggest that at high Ti(IV) concentrations, Ti(IV) could compete with Fe(III) to bind to biomolecules and would inhibit Fe bioavailability. At the typical Ti concentrations in the body, Ti might exist as a labile pool of Ti(IV) in cells, similar to Fe. Ti could exhibit different types of properties that would determine its cellular functions. We predict some of these functions to mimic those of Fe in the cell and others to be specific to Ti. Bone and cellular speciation and localization studies hint toward various intracellular targets of Ti like phosphoproteins, DNA, ribonucleotide reductase, and ferritin. However, to decipher the exact mechanisms of how Ti might mediate these roles, development of innovative and more sensitive methods are required to track this difficult to trace metal in vivo.

Keywords: Titanium(IV), serum transferrin, endocytosis, aqueous speciation, metal uptake, titanium coordination, titanium transport, titanium function, titanium storage, titanium bioaccumulation

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Titanium is a highly abundant element, widely recognized for its strength and long-term endurance and for these reasons it is incorporated in many different materials [1, 2]. Within the human body it is used for dental and orthopedic prosthetics [3, 4]. The metal, however, remains largely unappreciated for its biological importance despite many examples of its benefit to plants [5–8] and animals [9–11]. This response partly stems from the belief that Ti is nonessential to humans. One of the classical ways to assess the essentiality of an element is in medical studies designed to remove this element from food and to examine the impact of its absence on the health of human subjects [12]. If the subjects become unhealthy due to the element’s absence and then recuperate once the element is returned to the diet, the element is classified as essential. The reality is that no experiment of this type can be properly designed because Ti is so ubiquitous on the Earth (9th most abundant element at 4400 ppm) [13] that it is prevalent in foods and impossible to remove from specially made diets for these studies [14]. Where some credence can be given to the assumed non-essentiality of the metal is the lack of any finding showing that it is employed in a biological process such as a cofactor or coenzyme within the human body.

The low solubility of Ti in water [15] is seen as a strong indicator that it is biologically inert. In our oxidizing atmosphere, the metal exists as Ti(IV) and in aqueous solutions is highly Lewis acidic and extremely prone to hydrolysis. At the pH of blood (pH 7.4) many Ti(IV) compounds quickly dissociate and transform into titanium dioxide (TiO2), also known as titania. The older literature suggested that titania was virtually insoluble because it was based on using the Ksp of TiO(OH)2 (1×10−29), which predicts a solubility of 0.2 fM at pH 7.4 [15, 16]. In the pH range 3–11 and 25 ° C, titania solubility is actually ~1 nM due to the predominance of the Ti(OH)4 species [17]. As is true of other metals, metal binding by biomolecules in biological fluids greatly increases the solubility and, as a result, the potential bioavailability of Ti(IV). In human blood, titanium is far more soluble than its natural solubility in water. Although the reported titanium levels are inconsistent, several studies concur with the value of ~1 µM in whole blood [18–20]. Serum transferrin (sTf), the iron(III) blood transport protein, is almost exclusively responsible for this elevated concentration [21] by coordinating the metal at its Fe(III) sites [22–26].

Identifying a mechanism by which soluble titanium within the body has a physiological impact would be a groundbreaking insight into its biological activity. One important way to discover such a mechanism would be to investigate how the body responds to a significant influx of titanium in the bloodstream. There are several examples in the literature of organisms undergoing environmental adaptation due to a localized increase or decrease of elements in their surroundings that ultimately reveals a functional role of a metal. An excellent example of this is the discovery of a biological property of cadmium in the finding of cadmium-containing carbonic anhydrases (CDCA1) in marine diatoms [27, 28]. Typically, zinc(II) and not cadmium(II) is the metal cofactor at the active site of carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme used for buffering purposes and for biotransforming inorganic carbon for use in photosynthesis. As Zn(II) levels have become depleted in the oceans, diatoms have evolved their carbonic anhydrase to incorporate the Cd(II) available [28]. Prior to the discovery of this property, the metal was exclusively thought to be a toxic element. The relatively low ocean concentration of Cd(II) may allow diatoms to benefit from its biochemistry [29]. Nonetheless, it remains a toxic element to humans. A Bertrand diagram (Fig. 1), which classifies elements as essential, toxic, or therapeutic based on their dose-dependent physiological effect, would have to be organism specific for Cd(II). For diatoms, Cd(II) constitutes the category nonessential but functional. The dose response curve for Cd(II) in these organisms would likely appear similar to the essential plot model especially in the total absence of Zn(II).

Fig. 1.

A Bertrand diagram demonstrating the physiological effects of elements that are essential, toxic, or therapeutic. Reprinted from Biological Inorganic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity, Ed. 1, Ivano Bertini, Harry B. Gray, Edward I. Stiefel, and Joan S. Valentine, Chapter 7: Metals in Medicine, 96, Copyright 2007, with permission from University Science Books.

In this review, we explore the possibility of Ti(IV) playing the role of a nonessential but functional metal in the human body based on its chemical proximity to Fe(III). Ti(IV) and Fe(III) share several chemical properties. Like Ti(IV), Fe(III) is strongly Lewis acidic and extremely hydrolysis prone. Both metal ions form compounds with a preferred coordination number of 6, exhibiting similar ionic radii, 60.5 pm for Ti(IV) and 65 pm for Fe(III) [30]. As Lewis Hard acids, both metal ions bind to the same type of metal binding moieties and consequently can bind to the same biomolecules. Due to their comparable ligand affinity profiles [24, 31], it is logical that serum transferrin, known for its primary function as the transport agent for Fe(III) into cells via endocytosis [32–34], would also serve as the primary blood vehicle for soluble Ti(IV) [21]. In fact, Ti(IV) is the only other metal conclusively known to be transported by sTf although there is some evidence for sTf transport of manganese(III) [35, 36]. Where Ti(IV) and Fe(III) differ significantly is in their redox properties. Fe(III) is a highly redox active agent, easily fine-tuned by biomolecules to exist in the Fe(II) and Fe(III) forms but Ti(IV) is generally redox inert [31]. Interestingly, Ti in its 3+ form is an excellent reducing agent [37, 38]. This review will focus on understanding and hypothesizing about the biological fate of Ti(IV) in people by first dissecting the comparable coordination chemistry between Ti(IV) and Fe(III). This fundamental chemistry provides insights into physiological Ti(IV) speciation and into the biomolecular interactions that govern how Ti(IV) enters the body, is transported into the bloodstream, is delivered into cells, and is distributed throughout the body at relatively high levels without exhibiting toxicity. To elucidate a function and bioactivity of Ti(IV) in the human body, parallels will be drawn to Fe mobilization by serum transferrin and to key aspects of its intracellular trafficking and localization that dictate Fe utility. Important differences between Ti(IV) and Fe(III) will be emphasized especially in the context of coordination chemistry and reduction potentials that define differences in their chemical properties. Intracellular speciation of Ti in the +3 and +4 states will be considered as the oxidation states may impart functionality to the metal in ways that may make it mimic Fe or behave in its own specific ways. This review will also present the inhibitory effect that Ti(IV) can impose on the intracellular iron pools due to competition with Fe(III) for biomolecular binding, which can lead to potent cytotoxicity. By illustrating the factors that can lead to Ti(IV) cytotoxicity and that can dictate functionality as its relates to its chemical proximity to Fe(III), our objective is to identify molecular mechanisms that regulate Ti(IV) to facilitate its bioavailability and bioactivity in the human body.

2. Comparing the Ti(IV) and Fe(III) biological coordination chemistry

Understanding the fundamental aqueous coordination chemistry of Ti(IV) is necessary to elucidate its entry and trafficking throughout the human body and any potential function it may play because of important compounds it forms with endogenous biological chelators. Much of this chemistry parallels that of Fe(III) and we will explore this similarity and also relevant differences that define comparable and distinct properties between the two metal ions.

2.1. The low molecular weight biomolecule pool

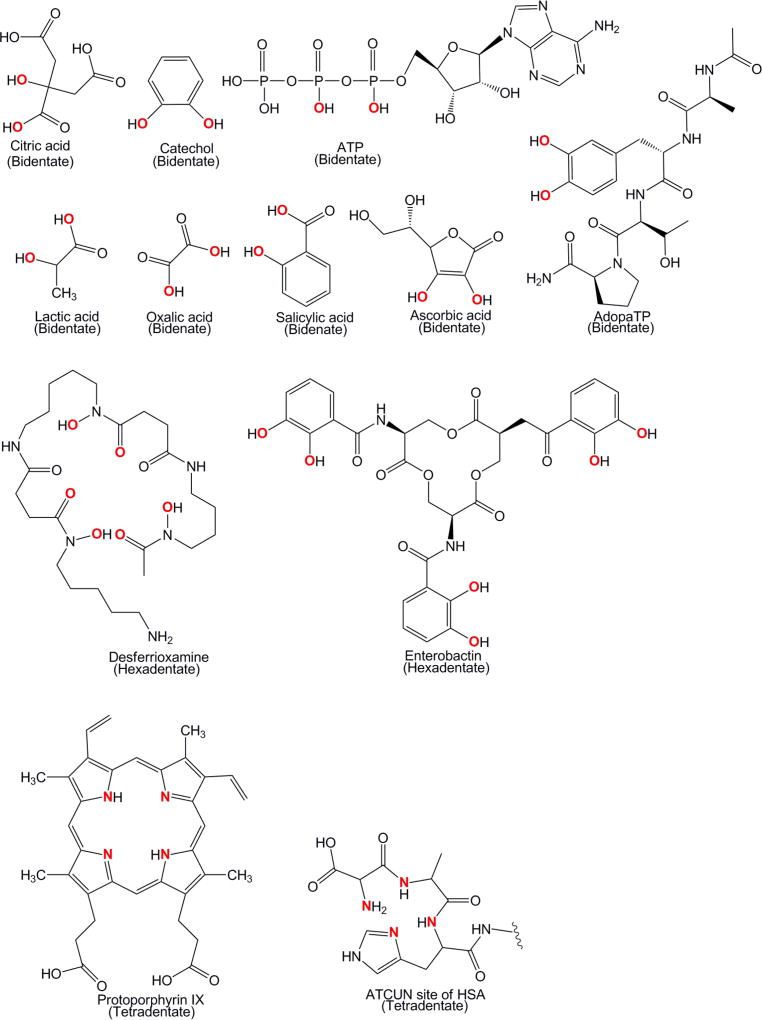

A recent review by Buettner and Valentine highlights the coordination chemistry of Ti(IV) with biological ligands. This material is helpful in identifying key features of the Ti(IV) interaction with the low molecular weight (lmw) biomolecule pool. Under physiologically relevant conditions Ti(IV) can form complexes with endogenous biological chelators that contain oxygen-rich binding moieties due to its Lewis Hard acid nature. These moieties include carboxylate, catecholate, hydroxylate, hydroxamate, peroxo, phosphate, salicylate, and tyrosinate groups (Fig. 2). The structure of pertinent endogenous biological ligands is shown in Fig. 3. Citric acid [39–43], lactic acid [44], and oxalic acid [45, 46] are able to coordinate Ti(IV) through carboxylate moieties. Citric acid and lactic acid also bind through hydroxylate groups, a property they share with ascorbic acid [47–49]. Citric acid can also form heteroleptic Ti(IV) complexes with peroxide. The peroxide coordinates to Ti(IV) as a η2 side-on peroxo group [50]. Catechol [51, 52], DOPA-containing peptides like AdopaTP (a synthetic peptide) [53], and the bacterial siderophore enterobactin [54] bind Ti(IV) via the catecholate moiety to form very high affinity complexes (log βTi(catechol)3 = 61.6) [51]. Desferrioxamine, also a bacterial siderophore, uses hydroxamate groups to coordinate Ti(IV) with high affinity (log βTi(desferrioxamine B) = 38.1) [55]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) likely binds Ti(IV) through two of its phosphate groups, the α and β ones [23, 56]. There has been one reported X-ray structure of a Ti(IV) salicylate complex, Ti(salicylate)32−, but this compound has not been characterized further [57]. Tyrosine is included in this list because presumably it can bind Ti(IV) when present in a peptide much like the DOPA amino acid. However, evidence for tyrosine binding of Ti(IV) is more readily available for the high molecular weight (hmw) biomolecule pool.

Fig. 2.

Characteristic Ti(IV) binding moieties of endogenous biological ligands. Represented here are coordination modes that have been reported in the literature but alternative modes are possible.

Fig. 3.

Endogenous biological Ti(IV) chelators. AdopaTP is an exception because it is not natural but DOPA-containing peptides are expected to bind Ti(IV).

Ti(IV) is also able to form complexes with lmw endogenous biological chelators that contain nitrogen atom donors but there are limited examples (Fig. 2 and 3). Peptide mimics of the ATCUN site of the blood protein serum albumin are likely to use the terminal amine, a histidine amino acid, and the nitrogen amide backbone to bind Ti(IV) [43]. Mass spectrometry data collected for the reaction of titanyl oxalate and the GlyGlyHis (GGH) ATCUN mimic suggest a Ti(oxalate)(GGH) complex. A structure was proposed in which an oxalate molecule is coordinated to Ti(IV) perpendicular to the coordination plane of the ATCUN moiety [43]. Further structural studies would provide better coordination insight. Protoporphyrin IX, the organic component of heme, can form a macrocyclic Ti(IV) compound [58]. This is also true of other tetrapyrrole ligands [59, 60]. The tetrapyrrole ligands bind Ti(IV) as a titanyl unit (TiO2+). The ATCUN mimic peptides might be able to do the same based on the only study done with this class of ligands. Mass spectrometry was used to propose a structure in which an oxalate molecule is coordinated to Ti(IV) in a plane perpendicular to the coordination plane of the ATCUN moiety [43].

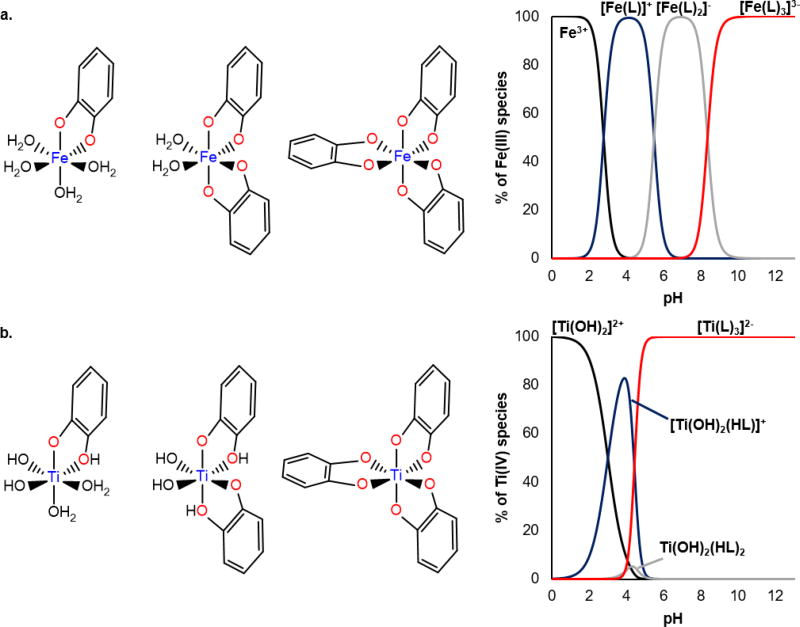

There are some subtle differences between the coordination chemistry of Fe(III) and Ti(IV) that likely dictates important distinctions in their chemical properties and molecular interactions and how they are trafficked in the body. These differences originate from Ti(IV) being a far stronger Lewis acid than Fe(III) as reflected by their primary hydroxide affinity constants (log KTiOH = 14.01 [61] versus log KFeOH = 11.6 [62]). An excellent case study to examine the manifestation of Lewis acidity differences is the pH dependent aqueous speciation of both metal ions with the catechol ligand. We will focus on the speciation from pH 0 to 13 using metal concentration of 50 µM and ligand concentration of 500 µM using the relevant formation constants listed in Table 1 [51, 52, 63]. Normally when considering metal aqueous speciation in the presence of a ligand, the metal is treated as a metal aqua complex, and the aqua molecules are formulated as competing with the ligand for binding the metal. With both Fe(III) and Ti(IV) having a preferred coordination number of 6, they would be considered as the species Fe(H2O)63+ and Ti(H2O)64+ and the ligand competition would be formulated according to equation 1.

| (eq. 1) |

Table 1.

Stability constants for Fe(III) and Ti(IV) catecholates.

| Equilibrium | Logβ | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| L2− + H+ ↔ [LH]− | 13.0 | |

| L2− + 2H+ ↔ LH2 | 22.24 | |

| Fe3+ + L2− ↔ [FeL]+ | 20.04 | [63] |

| Fe3+ + 2L2− ↔ [FeL2]− | 34.71 | |

| Fe3+ + 3L2− ↔ [FeL3]3− | 43.75 | |

| Fe3+ + H2O ↔ [FeOH]2+ + H+ | −2.19 | |

| Fe3+ + 2H2O ↔ [Fe(OH)2]+ + 2H+ | −5.76 | |

| Fe3+ + 3H2O ↔ Fe(OH)3 + 3H+ | −14.3 | [64] |

| Fe3+ + 4H2O ↔ [Fe(OH)4]− + 4H+ | −21.71 | |

| 2Fe3++ 2H2O ↔ [Fe2(OH)2]4+ + 2H+ | −2.92 | |

| L2− + H+ ↔ [LH]− | 13.4 | |

| L2− + 2H+ ↔ LH2 | 22.57 | |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + L2− + H+ ↔ [Ti(OH)2(HL)]+ | 22.9 | [51] |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + 2L2− + 2H+ ↔ Ti(OH)2(HL)2 | 43.5 | |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + 3L2− + 2H+ ↔ TiL3 + 2H2O | 61.6 | |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + H2O ↔ [Ti(OH)3]+ + H+ | −1.64 | |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + 2H2O ↔ Ti(OH)4 + 2H+ | −4.38 | [65] |

| [Ti(OH)2]2+ + 3H2O ↔ [Ti(OH)5]− + 3H+ | −15.26 |

Catechol is represented by LH2.

For both metal ions, however, metal hydrolysis plays a significant role (eq. 2), which adds a layer of complexity to the speciation study because hydroxo or even oxo groups have to be considered in the plausible species that can form in solution [64, 65].

| (eq. 2) |

At pH 0, Ti(IV) hydrolysis is already quite extensive and the metal exists exclusively as the dihydroxo species Ti(OH)2(H2O)42+ or Ti(OH)22+ for simplicity [65]. In the older literature (and because of uncertainty) Ti(OH)22+ was also represented as TiO2+[51]. At this same pH, Fe(III) is unhydrolyzed although it becomes hydrolyzed with a slight pH increase [64]. Throughout the pH 0 to 13 range, Fe(III) and Ti(IV) form comparable catechol-containing species including mono, di, and tricatechol metal species. As shown in Fig. 4a, Ti(IV) forms these species at lower pH values with respect to Fe(III). By pH 5.0 the Ti(IV) primary coordination sphere is fully saturated by catechol yielding the Ti(catechol)32− species [51]. This species remains the exclusive species up to pH 13.0. Above pH 13.0, Raymond et al. report dissociation of one catechol ligand accompanied by dimerization and metal hydrolysis producing the species [TiO(catechol)2]24− [52]. It is at pH 10.0 that Fe(III) is saturated by catechol (Fig. 4b) [63]. It is interesting to note the following in these pH profiles. Ti(IV) can form a higher affinity tricatechol species (log βTi(catechol)3 = 61.6) than Fe(III) (log βFe(catechol)3 = 43.75) [51, 63]. At the pH of blood (pH 7.4), Ti(IV) would most definitely outcompete Fe(III) for binding to catechol. Above pH 13.0, the story changes and Fe(III) outcompetes Ti(IV). This case study exemplifies how pH can regulate metal ligand affinity to finetune preference of one metal versus another. In the list of representative endogenous ligands featured in Fig. 3 for which aqueous speciation studies have been reported, Ti(IV) tends to form the corollary Fe(III) ligand complexes at lower pH values. This trend follows the ability of Ti(IV) to interact with hydroxo (or even oxo) ligands at lower pH values than Fe(III).

Fig. 4.

Aqueous speciation of Fe(III) (a) and Ti(IV) (b) in interaction with catechol over the pH 0 to 13 range. The speciation plots were constructed using the following concentrations ([metal] = 50 µM and [catechol] = 500 µM) and stability constants obtained from references 51, 63–65. To emphasize metal-catechol species that form, metal hydrolysis species were omitted from this analysis for the exception of [Ti(OH)2]2+ because it already exists at pH 0.

Generated using Species 3.2, a free online (www.acadsoft.co.uk) speciation application developed by L.D. Pettit, Academic Software (Sourby Old Farm, Timble, Otley, Yorks, LS21 2PW, UK).

A unique example of Ti(IV) stronger Lewis acidity than Fe(III) is the interaction of Ti(IV) with the citrate ligand (Fig. 5). Solid-state and aqueous speciation studies on homoleptic compounds of Ti(IV) citrate demonstrate that citrate coordinates Ti(IV) exclusively in a bidentate mode with the alpha carboxylate and alpha hydroxylate moieties [39–43]. For Fe(III), citrate serves as a tridentate ligand with the additional coordination provided by one of the beta-carboxylate arms [66, 67]. Ti(IV) can thus form tricitrate complexes with different protonation states depending on pH whereas Fe(II) can form dicitrate ones. These coordination modes allow Ti(IV) to bind more of the oxygen moieties in particular the hydroxylate group, a stronger Lewis base than the carboxylate group. Furthermore, the Ti(IV) species form only 5-membered rings upon citrate coordination, which is more stable than the mixture of 5, 6, and 7-membered rings from a tridentate coordination. Regardless of the differences in coordination modes, Ti(IV) and Fe(III) citrate compounds are extremely labile in solution and could undergo facile ligand exchange with other biomolecules [24–26, 67–71].

Fig. 5.

Citrate coordination of Fe(III), Ti(III), and Ti(IV). The structures depict citrate:metal ratios that result in saturation of the coordination sites of the metal (coordination number = 6).

2.2. The high molecular weight biomolecule pool

Similar to the interaction of Ti(IV) with the lmw biomolecule pool, Ti(IV) is bound by Fe(III) binding biomolecules of the hmw pool. The known examples are all proteins. Ti(IV) binds at the Fe(III) site of the highly homologous transferrin family of proteins, of which complexes have been reported for serum transferrin (sTf) [22–26, 43, 72], lactoferrin [73], and nicatransferrin (nicaTf) [74–76]. The Ti(IV)-sTf complex has been best characterized and it demonstrates metal coordination distinct from Fe(III).

STf is a bilobal, 80 kDa glycoprotein present at 30–60 µM in blood. Its N- and C-lobes are divided into two subdomains (N1 and N2, and C1 and C2) that form two high affinity Fe(III) binding sites (log Kc-site = 22.5 and log Kn-site = 21.4) [77–79]. Fe(III) is coordinated by an aspartate and histidine in the N1/C2 subdomains and two tyrosines in the N2/C2 subdomains [80]

(Fig. 6a i). The coordination is completed by the synergistic anion carbonate, which coordinates in a bidentate form [81]. The carbonate can be substituted by carbonate-like molecules but with certain size limitations [81]. Malonate is an example of a carbonate substitute (Fig. 6a ii). The carbonate is stabilized by an arginine residue (Arg124 and Arg456, at the N- and C-site, respectively) and is required for the specific binding of Fe(III) [82]. A characteristic ligand to metal transfer (LMCT) band at λ = 465 nm appears in the UV-Vis spectrum of Fe2-sTf-(CO3)2 due to the interaction of the tyrosine residues with Fe(III). The extinction coefficient for this absorbance is ε = 5,200 M−1cm−1 based on protein concentration and ε = 2,600 M−1cm−1 based on each lobe. This extinction coefficient does not change much with other carbonate-like synergistic anions but the λmax can range from 400 to 500 nm [81]. Fe(III) binding causes a dramatic conformational change from an open to close structure because the Fe(III) coordination brings the amino acids from the two subdomains in each binding lobe into closer proximity [83]. This conformational change leads to a significant increase in protein stabilization as demonstrated by the increase in melting temperatures of the two protein lobes measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC); 30 °C for the C-lobe and 19 °C for the N-lobe [83].

Fig. 6.

Serum transferrin coordination of different metals. (a) These structures represent different metal coordination modes. Structure i (PDB entry 3V83) demonstrates how STf coordinates Fe(III) in blood at its two identical metal binding sites, located one in each of its two lobes. The coordination involves two tyrosines one histidine, one aspartate, and a carbonate as a synergistic anion. Structure ii (PDB entry 3QTY) exhibits malonate as a carbonate substitute for Fe(III). Structure iii (PDB entry 4X1B) exhibits sulfate as an additional synergistic anion for Fe(III). Structures iv (PDB entry 3QTY) and v (PDB entry 5DYH) show sTf coordination of Bi(III) and Ti(IV), respectively. The Bi(III) and Ti(IV) structures show nitrilotriacetate (NTA) and citrate as additional synergistic anions, respectively. (b) Graphical representations of metal-bound sTf in an open and close conformation and an overlay between the two. c. Proposed structures for hydrolyzed Ti(IV) bound to sTf.

Ti(IV) also readily binds at both metal binding sites of sTf. An X-ray diffraction crystal structure for Ti(IV)-bound sTf was recently obtained and it is the first reported Ti(IV) protein structure (PDB entry 5DYH). It shows Ti(IV) coordinated in a manner distinct from Fe(III) [26]. Ti(IV) is bound by two of the four protein amino acids, the two tyrosines, carbonate, and citrate (in bidentate mode) as an additional synergistic anion in place of the histidine and aspartate residues (Fig. 6a v). The solid-state structure shows Ti(IV) bound only at the C-site but this is due to crystallization conditions involving very high citrate concentrations, which resulted in citrate competing with the protein for Ti(IV) binding and causing the dissociation of the metal at the N-site. The structure for Ti(IV) coordination was also confirmed in solution by a 13C NMR study using 13C-labeled citrate and bicarbonate. Following metalation in the presence of the labeled anions and sufficient protein dialysis, distinct chemical shifts were observed for coordinated citrate and carbonate [26]. Note that bicarbonate is deprotonated during the metal binding process. The coordinated citrate was also observed by an electrospray mass spectrometric analysis of the intact Ti2-sTf complex [84]. The differences between Fe(III) and Ti(IV) sTf binding suggest a difference in metal affinity, with the four protein amino acids combined having a higher affinity for Fe(III) than Ti(IV) owed to a difference in the Lewis Hard acid nature of the metal ions. Ti(IV) being a Harder acid would prefer binding to the Harder basicity afforded by the oxygen rich coordination (Fig. 6a v). The interaction of the tyrosine residues with Ti(IV) produces a LMCT absorbance shoulder at λ = 321 nm [24]. The extinction coefficient for this absorbance is ε = 20,800 M−1cm−1 based on protein concentration and ε = 10,400 M−1cm−1 based on each lobe [24]. Due to citrate binding, Ti(IV) is bound by sTf in an open protein conformation (Fig. 6b). The Ti(IV)-sTf X-ray protein structure overlays well with the apoprotein structure (PDB entry 2HAV) [85]. Ti(IV) improves sTf stability to a lower extent than Fe(III) as Ti(IV) is only able to bring sections of the subdomain containing the tyrosine residues in closer proximity. The DSC melting temperatures of the two protein lobes increase 18.5 °C for the C-lobe and 5 °C for the N-lobe [26]. STf in synergism with carbonate and citrate binds Ti(IV) with very high affinity (log Kc-site = 35.8 and log Kn-site = 34.7) producing the complex Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 [24, 26]. Neither the carbonate nor citrate anions are a requirement for sTf binding of Ti(IV) [23, 25]. Nonetheless, at the serum physiological concentration of both anions, 27 mM for HCO3− and 100 µM for citrate3−, both anions are expected to be coordinated to the Ti(IV) in the protein during blood transport and likely increase the rate of metal loading to the protein [25].

A genuine citrate-free Ti(IV) sTf complex can be prepared by reacting sTf with a highly labile Ti(IV) source such as the aqueous unstable titanocene dichloride compound [86] in the presence of blood levels of HCO3− [23, 26]. In this complex, carbonate serves as a synergistic anion as indicated by the use of H13CO3− and 13C NMR. The two Ti(IV) ions are probably bound as hydrolyzed species either as a titanyl unit (or its chemical equivalent Ti(OH)22+) (Fig. 6c). The existence of a LMCT absorbance in the same wavelength range as the citrate-bound structure suggests that the metal is tyrosine bound. We propose two possible structures showing Ti(IV) bound to two tyrosines and to one tyrosine at the binding site. That the extinction coefficient is ε = 4,830 M−1cm−1 based on protein concentration and is ε = 2,415 M−1cm−1 based on each lobe suggests that hydrolyzed Ti(IV) might coordinate to only one of the tyrosine residues. Aqueous speciation studies of Ti(IV) with the chemical transferrin mimetic (cTfm) ligand N,N'-di(o-hydroxybenzyl)-ethylenediamine-N,N'-diacetic acid (HBED) (Fig. 7) demonstrate that HBED models well the UV-Vis spectroscopy of unhydrolyzed (fully chelated metal) and hydrolyzed Ti(IV) bound by sTf. The ligand features two phenolate oxygens, two amine nitrogens, and two carboxylate oxygen coordinating atoms. At pH 3.0, the ligand serves as a hexadentate ligand fully saturating the coordination sphere of the metal [24]. At pH 7.4, one of the phenolate groups from the ligand dissociates transforming the ligand into a pentadentate chelator. Metal hydrolysis occurs leading to the formation of a titanyl unit [87]. The unhydrolyzed Ti(IV) HBED complex has a LMCT absorbance at λ = 365 nm and an ε value of 9,140 M−1cm−1 comparable to the LMCT band of each metal binding site of the citrate bound Ti2-sTf complex (ε = 10,400 M−1cm−1). The hydrolyzed Ti(IV) HBED complex has a LMCT at λ = 306 nm and an ε value of 4,570 M−1cm−1, which is a factor of two higher than the LMCT band of each metal binding site of the citrate free Ti2-sTf complex (ε = 2,415 M−1cm−1). The citrate free Ti2-sTf complex is expected to be in an open conformation. The DSC melting temperatures of the two protein lobes increase 2.7 °C for the C-lobe and 2.3 °C for the N-lobe [25], very moderate increases relative to the citrate-bound complex. The physiological relevance of the citrate-bound and citrate-free structures is discussed in the section 4.3.

Fig. 7.

Chemical transferrin mimetic ligands HBED (a) and deferasirox (b) and the corresponding pH-specific Fe(III) and Ti(IV) complexes.

Ti(IV) is predicted to bind to all members of the transferrin family of proteins that are capable of binding Fe(III) but only two other members have been examined for their Ti(IV) binding potential, lactoferrin and nicaTf. There is very limited structural characterization of the Ti(IV)-lactoferrin complex but presumably lactoferrin binds the metal in manners analogous to serum Tf because of their high homology (60 % sequence homology) [73]. NicaTf, a monolobal 40 kDa Tf from the ascidian Ciona intestinalis has an unusual Fe(III) binding site that does not exhibit the characteristic spectroscopic signals of the other Fe(III)-transferrin sites [74–76]. The spectroscopic signals for the coordinated Ti(IV) do not match those of sTf, which suggests a different mode of Ti(IV) coordination [74]. This protein is 36 % sequence homologous with sTf.

Ti(IV) is also expected to bind to all members of the family of gram negative ferric binding proteins (FBPs) known as the bacterial transferrins. Members that are pathogenic bacteria use this group of proteins to steal Fe(III) from mammalian host sTf and lactoferrin and then shuttle the metal across the periplasmic space and to facilitate virulence [88, 89]. The FBPs are structurally homologous with each lobe of mammalian Tf. The proteins have an Fe(III) binding site found in the cleft between the two domains. There are four classes of Fe(III) binding sites which are similar to the mammalian Tf Fe(III) binding site. All of the sites include two to three tyrosine residues but not all include histidine or aspartate (or its equivalent, glutamate) and not all require a synergistic anion [88–92]. Sadler et al. studied the Ti(IV) binding of Neisseria gonorrhoeae FBP. These bacteria contain the Fe(III) class 1 site, which consists of two tyrosines, one histidine, one glutamate, a water molecule, and phosphate as a monodentate synergistic anion. Interestingly, citrate can substitute for the phosphate as a synergistic anion but it is proposed to coordinate in bidentate mode [93]. The N. gonorrhoeae FBP was reacted with titanocene dichloride under citrate-free conditions and physiological levels of phosphate. An EXAFS analysis of the Ti(IV)-FBP structure indicated that the Ti(IV) was coordinated as a titanyl unit, bound by the two tyrosines, and possibly three water molecules [92]. A LMCT absorbance shoulder appears at λ = 323 nm due to the tyrosine-Ti(IV) interaction. The extinction coefficient for this absorbance is ε ~ 6,000 M−1cm−1. This value is between that of citrate-bound Ti-sTf and citrate-free Ti-sTf and indicates that the citrate-free Ti-sTf structure may involve only one Ti(IV)-tyrosine bond.

Ti(IV), like Fe(III), can bind to serum albumin but only in compound form. Human serum albumin (HSA) is a 65 kDa glycoprotein with three homologous domains and is the most abundant blood protein, up to 700 µM in serum [94]. It has four metal binding sites that bind Lewis soft and intermediate metals [95]. These sites are not suitable for Fe(III) and Ti(IV) binding. One of the sites is the classical amino terminus ATCUN site (Fig. 3), which binds Cu(II) and Ni(II) with very high affinity [96]. This site has very poor Ti(IV) affinity as determined with an ATCUN peptide mimic GlyGlyHis [43]. Due to its numerous ligand and drug binding sites, HSA can bind an extensively diverse set of hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds [97, 98]. For this reason it can bind Fe(III) compounds [99, 100] and several Ti(IV) compounds including Ti(IV) citrate as a monocitrate species [43], Ti(IV) ascorbate, the titanocene moiety [43, 101], and Ti(IV) trisnaphthalene-2,3-diolate (a catechol type ligand) [102]. The Ti(IV) compounds appear to bind at multiple sites with low to moderate affinity. The Kd is 0.5 µM for the primary binding site of Ti(IV) trisnaphthalene-2,3-diolate [102]. One equivalent of each of the compounds remains protein-bound following separate binding reactions with the compounds and extensive protein dialysis. None of the primary sites has been identified for any of these compounds.

The only nonprotein high molecular weight biomolecule that has been shown to coordinate Ti(IV) is DNA [103–106]. In vitro studies with the B-form of DNA demonstrate that Ti(IV) mainly binds to the phosphate backbone [4, 107]. Ti(IV) can also bind to the nitrogen atoms of the nucleotides although weakly [103, 107–109]. No structure for DNA coordination of Ti(IV) has been proposed but cell studies indicate that Ti(IV) can localize to the nuclear region and likely bind to DNA [110–112]. This interaction will be later discussed further in the section 4.4.

2.3. Comparing the reduction potentials of corollary Ti(IV) and Fe(III) compounds with biological ligands

A highly insightful study was performed by Crumbliss et al. to compare the reduction potentials between Ti(IV) and Fe(III) compounds of the same biological ligands using data available from the literature [31]. The numbers used were those corresponding to aqueous conditions in which the ligands fully saturated the primary coordination sphere of each metal. As our analysis of the aqueous speciation of Ti(IV) and Fe(III) in the presence of catechol suggests, different pH values are often necessary for full ligand saturation to occur. A plot of the Ti(IV) reduction potentials versus the Fe(III) reduction potentials produced a linear trend with outliers attributed to differences in the modality of ligand coordination to the metals (Fig. 8). The trend reveals that the Ti(IV) reduction potentials are much smaller than the Fe(III) reduction potentials, meaning that given the same ligand, it is harder to reduce Ti(IV) to Ti(III) than to reduce Fe(III) to Fe(II). This is not to imply that it would be impossible to reduce Ti(IV) in vivo. A comparison between the reduction potentials of aqueous Ti(IV) and Fe(III) ions under acidic conditions (pH 0) shows that both reduction events are thermodynamically favorable: TiO2+/Ti3+; E0 = +0.09 V and [Fe3+/Fe2+; E0 = +0.77 V vs NHE [113]. The more positive value for Fe(III) indicates that it is more thermodynamically favorable. The actual conditions in vivo might be more complicated due to the impact of solute concentration, pH, and the complexing ligands as seen in the case of vanadium(V). V(V) is a highly stable ion in our oxidizing environment but is easily reduced to V(IV) in the presence of thiol-containing molecules as studied by Crans et al. [114]. Ligand coordination can fine tune the redox potential of metal ions and in some cases, stabilize one oxidation state. Were aqueous Ti(IV) ions to maintain a reduction potential near E0 = +0.09 V and remain soluble they would easily reduce to Ti(III) in the highly reducing conditions of the cellular environment. Ligand coordination of Ti(IV) can greatly lower its reduction potential as observed with catechol like ligands, which lower the value to ~−1 V vs NHE coordination sites and effectively stabilize the Ti(IV) oxidation state [52, 102]. The different redox properties of both metal ions Fe(III) and Ti(IV) and how they possibly impact their transport and localization in cells will be further discussed in the section 4.4.

Fig. 8.

The plot of measured E1/2 values for Ti(IV) complexes as a function of measured E1/2 values for corollary Fe(III) complexes of biological ligands. The solid line represents a linear least squares fit to data points for complexes containing amine carboxylic acids (HBED, CDTA, EDTA, and DTPA). The dashed line represents a linear least squares fit to data points for complexes containing amine carboxylic acids and the catechol moiety. Reprinted from Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 104, Claire J. Parker Siburt, Emily M. Lin, Sara J. Brandt, Arthur D. Tinoco, Ann M. Valentine, Alvin L. Crumbliss, Redox potentials of Ti(IV) and Fe(III) complexes provide insights into titanium biodistribution mechanisms, 1006–1009, Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier.

2.4. Outlook

Of the Ti(IV) compounds presented here, Ti(IV) citrate, Ti(IV) ascorbate, Ti(IV) ATP, Ti(IV)-bound sTf, and Ti(IV)-bound DNA are the ones with the most in vivo relevance in the human body. The role of pertinent species of these compounds and the interplay between these species will be discussed to understand how Ti(IV) enters the body, is transported in blood, and is delivered to cells. The fundamental aqueous coordination chemistry helps us to predict new Ti(IV) compounds that may form in the body and to postulate on intracellular speciation, both biomolecular events that can define Ti(IV) bioactive properties specific to the metal and also those related to Fe biochemistry in ways that may be beneficial and harmful to people.

3. Titanium in the body

Titanium can enter the body in different ways, two of the main routes being food and drink consumption and inhalation. In the U.S., people ingest high quantities of Ti daily (200–300 µg Ti/day), even patients receiving total parenteral nutrition [16]. Some of this Ti is in the form of Ti(IV) compounds like Ti(IV) citrate and Ti(IV) ascorbate, which are supplied as nutrients to enhance crop growth [6, 8, 115]. Dietary Ti also exists in the form of food-grade TiO2, used as a whitening and brightening agent [116]. TiO2 is abundant in other daily products including toothpaste, makeup, sun tan lotion, and white paint. Dust containing TiO2 particles is inhaled and leads to Ti accumulation in the lungs, where it is found at its highest levels in the body [117].

Another route of Ti entry into the body is via titanium-containing implants. Due to its high biocompatibility and property of osseointegration [118, 119], Ti is commonly used in dental, orthopedic, and prosthetic implants, which are placed in hundreds of thousands of people each year [118]. With life expectancy continuing to increase, a significant portion of the human population will be impacted by these materials. The Ti, however, is not as robust as previously thought. The metal at the surface is quite reactive with the surrounding biological fluid and can leach into the bloodstream. Ti in the blood of people with Ti-implants reaches levels roughly 50 times higher than people without. There are concerns about health risks posed by the long-term presence of this influx of Ti [120, 121]. A portion of the Ti is released in the form of TiO2. Several studies reveal that nanoparticle TiO2 exhibits the ability to generate reactive oxygen species and can thus be strongly cytotoxic [117, 122]. This behavior, however, is photo-induced and not readily possible within the body, also released TiO2 is of an amorphous and not nanoparticulate nature. The reality is that no toxicity of this form has actually been reported in patients [123, 124]. The biological fate of TiO2 and its properties within the human body are likely to be quite different from those of soluble Ti(IV) and thus will not be the focus of our review.

That a soluble Ti pool exists in humans opens the door to contemplating human environmental adaptation to the metal especially in light of Ti leaching from implants. An effective concentration of ~80 µM soluble Ti(IV) formulated under physiologically relevant conditions at pH 7.4 has been shown to result in an appreciable amount of cytotoxicity in a screen of cell lines [125]. Based on the average blood volume of people (45.5 mL/kg) [126], this would translate to Ti(IV) reaching levels of 3.82 µg/mL (0.174 mg/kg body mass) in the bloodstream. With serum Ti levels ranging from a low of 239 pg/mL (0.0109 µg/kg; people with no Ti-implants) to a high of 12.0 ng/mL (0.545 µg/kg; people with Ti-implants) [21], it is present far outside the window of toxicity but well within the ballpark range of metals known to be essential. It is only 100 times less abundant than iron in serum [12]. In the body, Ti is widely distributed in organs and tissue, reaching its highest levels in the kidney cortex and lungs (1.3 mg/kg) [120]. These levels are considerably higher than the highest human bloodstream levels, even exceeding the blood toxicity levels and yet no organ damage has been reported. This evidence is strongly indicative of bioaccumulation and the possibility that Ti serves a function in the body.

4. Ti(IV) blood transport and cellular uptake

4.1. Exclusivity of labile ‘ionic’ Ti(IV) binding to serum transferrin

Regardless of the route of entry into the body, Ti(IV) appears to be exclusively bound by sTf in blood as measured by mass spectrometric methods [21]. Ti(IV) is, in fact, the first noniron metal to be shown to be endogenously trafficked by this protein. Serum transferrin primarily binds circulating plasma iron in a bioavailable Fe(III) form for delivery into mammalian cells. It also serves an antibacterial role by sequestering the metal from opportunistic bacteria [127–129]. A lesser studied but very important property of sTf is as a noniron metal transporter. STf is typically 39% Fe(III) saturated [130], with plenty vacancy to transport other metals. Its metal binding sites favor coordination of strongly Lewis Hard acidic metal ions due to the presence of the tyrosine amino acids [131]. STf aids in the delivery of therapeutic metals (chromium, bismuth, gallium, indium, ruthenium, and vanadium), enhancing their activity and also toxic metals (aluminum, lanthanides, and actinides) with possible detrimental effect on human health [36, 132]. Although sTf participates in the cellular delivery of these metal ions, this trafficking role only occurs when the ions are present at elevated levels.

It is surprising that Ti(IV) binds exclusively to sTf considering serum albumin is 10 to 20 times more abundant in blood than sTf and can bind Ti(IV) in compound form. An explanation for this finding must consider the speciation of labile ‘ionic’ Ti(IV) once released into the bloodstream. Recall that Ti(IV) citrate and Ti(IV) ascorbate (and probably other small Ti(IV) compounds) from crops and leached Ti(IV) from Ti-containing implants are the main sources of labile ‘ionic’ Ti(IV). We and others have collectively shown that the bioactive anion citrate is likely responsible for the uptake of the metal and delivery to sTf [26, 133, 134]. This is the proposed transport mechanism for Ti(IV) released from implants. Citrate is quite abundant in the body, present in blood (~100 µM), synovial fluid in the peri-implant space (~200 µM) [135], and in ~0.3% by weight of teeth and bone [136]. A pH dependent speciation model using citrate concentrations in bodily fluids and serum Ti(IV) concentrations predicts that citrate can rapidly and completely capture the Ti(IV) and transiently form Ti(citrate)38− before reacting with sTf [41] to produce the Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex [26]. Due to the stabilization afforded to Ti(citrate)38− by the metal free serum citrate, the compound would not be able to undergo partial ligand dissociation that would generate a Ti(IV) monocitrate compound capable of binding to HSA [43, 137]. This evidence points to sTf having a much higher affinity for the Ti(IV) citrate species than SA, a difference that must exceed the concentration difference between SA and sTf. A positron emission tomography (PET) study performed on EMT-6 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice administered with 45Ti(IV)-citrate showed exclusive binding of the metal to sTf [138]. The 45Ti(IV)-sTf entered into the tumor cells.

The mechanism of Ti(IV) transport is similar for ingested Ti(IV) from Ti(IV) citrate and Ti(IV) ascorbate. Following metabolism, Ti(IV) can be absorbed by the gut and possibly use iron transport routes to travel from the gut and into the bloodstream [139]. There are several changes in pH in the process leading from ingestion, metabolism (pH ~2 in the stomach), gut absorption, and transport into blood. The speciation of Ti(IV) in interaction with citrate suggests that the Ti(IV) would remain soluble throughout this process [41] and even if there is some ligand dissociation, the Ti(IV) would become citrate saturated upon blood entry. The situation would not be identical for Ti(IV) ascorbate. A PET study of rats injected with 45Ti(IV)-14C-ascorbate demonstrated that the compound was bound by SA [140]. The biological fate within the body of the metal and ligand, however, was not identical indicating compound dissociation as part of the process of Ti(IV) localization. Oral ingestion of Ti(IV) ascorbate will probably not lead to significant interaction between the compound and SA. In its transport from oral ingestion to the blood, the pH changes would lead to extensive changes in speciation and a low effective concentration of Ti(IV) ascorbate species reaching the blood. At the pH of blood, Ti(IV) ascorbate species have low stability constants and would eventually dissociate [47]. Due to its higher affinity for Ti(IV), serum citrate would be able to readily coordinate the Ti(IV) from ascorbate. Valentine has shown the feasibility of ligand exchange between ascorbate and citrate [47]. Ultimately the Ti(IV) would be delivered to sTf.

4.2. The regulatory uptake of Ti(IV) by sTf in synergism with citrate

The synergistic interaction between sTf and citrate in coordinating labile ‘ionic’ Ti(IV) reveals a molecular mechanism to regulate the blood speciation of Ti(IV) and in turn, its reactivity. The property of citrate as a metal transporter in humans has not been well characterized [35, 141, 142] but it has been studied in bacteria [143, 144]. By rapidly binding the Ti(IV) that enters the bloodstream, citrate creates a transiently stable Ti(IV) compound that prevents uncontrolled TiO2 precipitation in amorphous form and of uncontrolled size that could lead to systemic health effects. The precipitation is further prevented by the even more stable complexation provided by sTf in conjunction with citrate. This preventative metal precipitation regulation is also true of Fe(III) released in blood. The second, not as obvious level of regulation is the formulation of the metal as a nontoxic species. Several Ti(IV) complexes are cytotoxic and some can kill cells at nM concentrations. At least 50 years of research has been devoted to the development of Ti(IV) anticancer compounds [145]. In the presence of physiological levels of citrate and sTf, the cytotoxicity of some of the complexes is greatly diminished due to induced dissociation by citrate binding and then scavenging of the metal by sTf [26, 69]. The Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex is not cytotoxic even at 100 µM concentration [87]. In the case of Fe(III), sTf coordination inhibits its reduction to Fe(II) in the blood, which would otherwise lead to uncontrolled production of reactive oxygen species. HSA may also participate in the molecular mechanism to reduce the cytotoxicity of some Ti(IV) compounds by binding the compounds and inhibiting either their uptake in cells or release within cells [87, 145, 146]. There are, however, a few exceptions. Titanocene Y is only cytotoxic in MCF-7 when bound to SA [101].

4.3. Serum transferrin endocytotic transport of Ti(IV) into cells

STf uses an endocytotic process for intracellular delivery of metals through interaction with its receptor (TfR). After the endosome enters the cell, a pH decrease from 7.4 to 5.5 occurs. A series of steps then leads to Fe escape from the endosome but the order of these steps is debated [32–34]. Some argue that the decrease in pH induces release of the metal from the protein, which then is reduced to Fe(II) by the Steap3 protein [32, 147]. Others argue that the pH change causes a structural reorganization of the sTf-TfR complex which alters the reduction potential of Fe(III) so that it is within the redox window of Steap3. The Steap3 then directly reduces the metal at the sTf binding site, significantly weakening the metal affinity to the protein and causing it to dissociate [33, 34]. Regardless of how the ferrous ion is formed, it is agreed that Fe(II) is transported out of the endosome and into the cytosol via the divalent metal transporter (DMT1). A labile iron pool forms in the cytosol that is then trafficked for utilization and storage.

The iron binding associated conformational change of sTf is believed to be important for recognition of sTf by the TfR at the cell membrane [148]. ApoTf, with its open conformation, is expected to have a very poor affinity to the receptor at pH 7.4 but a mass spectrometric study performed near this pH demonstrated that apoTf can indeed form a stable complex with the receptor [149]. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that a closed protein conformation is a requirement for endocytosis of metal-bound sTf. In support of this proposal, a study on plutonium(IV) uptake into cells revealed that only a closed conformation sTf structure resulted in cellular uptake of the metal [132]. The authors used small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) to analyze the structure of different formulations of Pu(IV) bound sTf including the homonuclear Pu2-sTf complex and the heteronuclear mixed Fe(III)/Pu(IV) complexes Puc-sTf-Fen and Fec-sTf-Pun. The Puc-sTf-Fen complex is a closed protein complex with a global conformational structure comparable to Fe2-sTf. A mixed Fe(III)/Pu(IV) sTf complex is plausible because part of the Fe(III)-sTf pool consists of mononuclear Fe(III)-sTf. The authors never specify whether any synergistic anion is involved in these structures and do not perform any actual in vivo studies, which calls into question the physical reality of this study.

That the Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex is able to deliver Ti(IV) into cells counters the notion of a closed conformation metal-bound protein requirement. A Ti(IV) uptake experiment was performed on A549 cells, known to overexpress the TfR, by incubating the cells with micromolar amounts of the protein complex. Treated cells were found to have twice the Ti(IV) level than untreated cells [26]. This finding complements the results of two other cell studies. One of these studies is the previously reported PET work performed on EMT-6 tumor-bearing BALB/cPEI mice showing 45Ti(IV)-sTf uptake into the cells following administration as a 45Ti-citrate compound [138]. The other is an intracellular mapping work undertaken using X-ray fluorescence (XRF). In this work V79 Chinese hamster lung cells were treated with titanocene dichloride in a fetal calf serum containing media. The Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex is expected to form in situ due to the micromolar amounts of citrate and sTf in commercial serum [26]. Though pushing the detection limits of the instrument, the Ti(IV) was observed distributed throughout the cells but more concentrated in the nuclear region [150]. Presumably the hydrolyzed Ti2-sTf-(CO3)2 complex (Fig. 6c) would also deliver Ti(IV) to cells considering the differences of the molecular details at the metal binding site should have no impact on the contact between the open conformation protein and the TfR.

In total, these studies suggest that although a closed conformation protein may not be a requirement for metal cellular uptake, it optimizes the total metal uptake. This optimization is the product of a higher affinity to the TfR. Of the different Pu(IV)-sTf structures, Puc-sTf-Fen complex is the only one that is a closed conformation structure and has the highest affinity for the receptor and results in the highest uptake of Pu(IV) [132]. The Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex binds with high affinity to the two binding sites of TfR1 (KD1 = 6.3 nM and KD2 =410 nM) but is weaker than the affinity of Fe2-sTf-(CO3)2 as measured by surface plasmon resonance (KD1 = 0.73 nM and KD2 =4.1 nM)[43]. The Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2 compound has been detected as a stable TfR1 complex by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry [84]. The missing carbonate anions are likely a result of the ionization conditions as was true of studies performed with the Fe2-sTf compound [151].

The “true” nature of the Ti(IV)-sTf complex is hard to define. It is possible that like Pu(IV), Ti(IV) could form mixed Fe(III)/Ti(IV)-sTf complexes. Ti(IV)-sTf isolated from human blood was observed to have Ti(IV) bound only at its N-site [21]. This finding indicates that the C-site may be more labile than characterized in vitro and could be available for binding of other metals, most likely Fe(III), which is more abundant in blood than Ti(IV). There is a crystal structure for a mixed Fe(III)/Bi(III)-sTf complex (PDB entry 3QTY) [152]. More and more identifying the “true” nature of any metal-bound sTf is complicated because of the impact that anions can have on the structure of the protein. There are now more structures known of other metal-bound sTf complexes in an open conformation such as that of Bi(III) [the one alluded to above] (Fig. 6a iv) and even of Fe(III) (Fig. 6a iii). The Bi(III) example may be a crystallization artifact but its shows the nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) ligand blocking the binding of the His, Asp, and one Tyr residue [152]. In the Fe(III) example, sulfate serves as a bidentate ligand that inhibits His and Asp binding [152]. In a way it is like the Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 complex in that both sulfate and citrate are not substitutes for the carbonate synergistic anion [81] but can serve as additional synergistic anions, something that was not thought possible previously. These structures provide insight into how non-carbonate, physiological anions can work in synergism to transport metals perhaps preparing them for alternative mechanisms of release from the protein.

The release of Ti(IV) from sTf in the endosome is expected not to involve metal reduction to Ti(III), which would lower its affinity for sTf [25]. Due to its highly negative value, the measurement of the reduction potential of Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 at endosomal pH using an electrochemical mediator could not be achieved. The value had to be predicted from the linear correlation between the reduction potentials of corollary Ti(IV) and Fe(III) complexes with ligands that mimic the sTf metal binding site [31] (See section 2.3). The value was determined to be −900 mV (vs NHE). Even when adjusting the value by ~230 mV positive for binding to the receptor TfR in a manner analogous to what has been observed for Fe(III), the value of −670 mV (vs NHE) is extremely negative and outside the biologically accessible range of >−400 mV (vs NHE) [31]. Ti(IV) oxidation state would remain stable. The reduction potential for the hydrolyzed Ti2-sTf-(CO3)2 complex was directly measured by placing the protein in a PEI film. Adapting the number reported at endosomal pH for film-free conditions, the reduction potential is estimated to be −930 mV (vs NHE), which is very similar to that of Ti2-sTf-(citrate)2(CO3)2 [31]. The similarity of the values matches well the similar values measured for the Ti(IV) complexes of the cTfm ligand HBED (Fig. 7). The reduction potential of the unhydrolyzed TiHBED compound is −641 mV (vs NHE) and that of the hydrolyzed complex TiO(HBED)− is −600 mV (vs NHE) [25].

Nonreductive release of Ti(IV) from sTf must consider the effect of pH and endosomal chelators. The endosomal pH does not weaken the affinity of Ti(IV) for sTf in the presence of 100 µM citrate as monitored by tracking the change in the LMCT absorbance of the complex [25]. However, as seen in the Fe(III) case, it may cause for a structural reorganization that could release the Ti(IV) as a hydrolyzed Ti(IV) monocitrate complex. Alternatively, if the concentration of citrate in the endosome falls below 10 µM, citrate will dissociate from the metal [137] leading to the formation of hydrolyzed Ti(IV)2-sTf and then the drop in pH might be enough to weaken the affinity of the metal to the protein. Another possibility was proposed by Sadler et al [23]. They suggest that because of its high affinity to Ti(IV) at endosomal pH, ATP can sequester Ti(IV) from the protein. These mechanisms would lead to the formation of different possible Ti(IV) species such as Ti(citrate)(ATP) or TiO(ATP) and TiO(citrate) and also their nonhydrolyzed forms because the exact stoichiometry would not be possible to state. The reduction potential of these compounds [71] may also be outside the potential window of the Fe(III) reducing agent, Steap3, making reduction of Ti(IV) in the endosome not likely. It is not clear whether any of these species could passively diffuse through the endosomal membrane. However, an interesting possibility is that the titanyl unit from TiO(ATP) and TiO(citrate) species being a 2+ ion might be recognized by the DMT1 and directly transported out of the endosome [153]. The vanadyl unit (VO2+) is transported by DMT1 [154]. A collaboration between Garrick, Valentine, and Tinoco to study DMT1 transport of Ti(IV) in cells treated with small molecule Ti(IV) compounds was inconclusive [155].

4.4. Contemplating cellular trafficking, storage, and utilization of Ti(IV)

Whether Ti(IV) is released as TiO2+ via DMT1 or as a small molecule Ti(IV) citrate and/or ATP compound into the cytosol, it is anticipated that a labile Ti pool would exist, even if transiently as is true for blood, within cells. That part of this pool may consist of Ti(III) species has been suggested [156]. Ti(III) is an even better mimic of Fe(III) than Ti(IV). The ionic radius of Ti(III) (67 pm) is close to that of Fe(III) (65 pm) [30]. Although the coordination chemistry of Ti(III) is not well-studied, it may be quite similar to Fe(III). For instance, based on mass spectrometry studies we predict that Ti(III) chelation by citrate displays the same tridentate coordination that is characteristic of the ligand’s coordination of Fe(III) and can form a Ti(III) bicitrate complex upon ligand saturation (Fig. 5) [71]. Ti(III) is also a very good redox agent like Fe(III), which serves as a reducing agent [37] capable of contributing to the formation of reactive oxygen species in cells. In the form of Ti(III) citrate, it is a very soluble species that can reduce different metal centers of metalloenzymes and can participate as a reducing agent for enzyme-catalyzed redox processes [38]. Ti(III) citrate has been shown to react with the intracellular protein ferritin, which is the Fe storage protein. This protein stores Fe via a biomineralization process by capturing Fe(II) from the labile pool and then oxidizing it to Fe(III) using a ferroxidase center. A precipitation event occurs leading to the formation of ferrihydrite (Fe2O3·nH2O). As many as 4,500 atoms of Fe can be stored in a ferritin molecule [12]. Ferritin can biomineralize Ti within its core in the form of a hydrated TiO2 particle [156, 157]. No study as of yet has been conducted to demonstrate the ability of ferritin to store Ti in cells, which would be a very valuable observation because storage of a metal implies use of the metal. Ferritin biomineralization of Ti might account, in part, for the organ accumulation of Ti.

Although Ti(III) is ripe for very interesting biological properties, it is not likely to exist in the cellular environment via Ti(IV) reduction. The standard reduction potential of TiO2+ is +0.09 V (vs NHE at pH 0). However, under acidic conditions reduction of TiO2+ involves a proton and is thus a pH dependent process. The reduction of Ti(IV) would depend on factors like ligand concentration and the pH of subcellular localization [158]. At the cytosolic pH of 7.4 and in the presence of certain cellular ligands like citrate that can form stable but labile Ti(IV) complexes, the Ti(IV) reduction potential would be expected to be lower (E0 < −0.8 V (vs NHE) for Ti(citrate)3 at pH 7.0) [71]. The cytosolic Ti(IV) reduction potential would be expected to be outside the redox window of intracellular reducing agents (see section 2.3) such as glutathione (E0 = −0.23 V (vs NHE) at pH 7.0), which is also a metal chelator prevalent in cells at low mM concentrations [159]. It is one of the key reducing agents that maintains the labile Fe pool in cells dominantly in the ferrous ion (Fe(II)) form. Fe(II)-bound glutathione is believed to be one of the major species of this pool [160].

In the form of a labile Ti(IV) pool in the intracellular environment, the metal can play several important functions. Ti(IV) could participate in acid/base catalysis because as Zierden and Valentine note, Ti(IV) being a strongly Lewis acidic metal can deprotonate difficult-to-deprotonate substrates [161]. Through its association with phosphate groups, Ti(IV) can engage in different biochemical processes. At pH 7.4, Ti(IV) ATP species undergo phosphate hydrolysis of the γ-phosphate like Fe(III) ATP. Both metals may participate in transporting these phosphate groups to other molecules such as in phosphorylation. Ti particles has been shown to induce phosphorylation of proteins in macrophages [162] although the molecular details of this mechanism are not known. Biomolecular coating of the particles can alter protein phosphorylation [162]. ATP is present in cells at high concentrations (low mM) and plays an important function in transporting Fe(III) in the form of an ADP complex to the nucleus [56]. ATP could similarly deliver Ti(IV) as Ti(IV) ADP to the nucleus [23, 56]. An electron-spectroscopic imaging (ESI) study of mice xenografted with human tumors and treated with titanocene dichloride revealed nuclear accumulation of Ti(IV) [110]. The Ti(IV) signal co-localized with the phosphorus signal. This co-localization might indicate Ti(IV) binding to the DNA phosphate groups or it might be the result of ATP delivery of Ti(IV) combined with Ti(IV) transfer to other phosphate-containing biomolecules including DNA. At very high concentrations (~10 mM) the Ti(IV) can cause DNA damage but at 100 µM, there is no evidence of harm [163].

Labile Ti(IV) may also become affiliated with the intracellular phosphoproteome. The same ESI study described above showed that Ti(IV) co-localized with phosphorus in the cytoplasmic lysosome, an organelle used for the degradation and recycling of cellular components [110]. Lysosome is rich with phosphoproteins including phosphoproteases. Observation of the Ti(IV) signal in the lysosome does not imply that it is only affiliated with the phosphoproteome at this site. Detection by the ESI technique requires significant metal accumulation and this is the site that meets this criteria because it is the center of degradation. Ti(IV) may play a structural role for proteins, a function commonly associated with Zn(II) and Ca(II) but to a lesser extent for iron and copper ions [12].

A structural templating role is indeed a function that Ti already plays in the human body. As mentioned previously, Ti through Ti-containing implants exhibits the property of osseointegration in the body, able to integrate with bone without the requirement of soft tissue connection. A recent study was done of a small Ti-containing implant removed from a person, using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) [164]. The implant contained a bone attachment. At the interphase between the bone and implant layers, Ti, C, Ca, O, and P could be detected (Fig. 9). According to the EELS spectrum, the Ti at the interphase undergoes a chemical modification as it interacts with the hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) type crystallization of bone indicative of it playing an active role in the structural templating process of bone development and growth (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Analysis of the contact between small Ti-containing implant and human bone. (a) Dark-field TEM images of the bone, interface, and implant layers. In the dark-field view, a diffraction pattern characteristic of hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH)) of bone are observed both in the bone and in the amorphous interface layer. And the obtained electron diffraction pattern of each is shown. The crystalized layer pattern matched hydroxyapatite of bone. (b) The EELS spectra exhibit the elements present in the implant, interface, and bone layers. Reprinted from BioMed Research International, 2015, Jun-Sik Kim, Seok-Man Kang, Kyung-Won Seo, Kyung-Yen Nahm, Kyu-Rhim Chung, Seong-Hun Kim, and Jae-Pyeong Ahn, Nanoscale bonding between human bone and titanium surfaces: Osseohybridization, Copyright 2015. cc

In this same vein, Ti(IV) could play a formative role in babies and young children. McCue reports that Ti(IV) fed to mice pups enhanced their growth [11, 165]. It is quite abundant in human milk (5.2 µM), even higher than in blood. Milk, in general, could serve as another route of Ti(IV) entry into the human body, as it is likely to be stably bound by the lactoferrin protein [73] and readily metabolized. McCue also observed an antibiotic property in the animals studied, a property also shared by lactoferrin and sTf. Perhaps there is a link between Ti(IV) binding by lactoferrin and sTf and its antibiotic nature, one that could be synergistic. Ti(IV)-bound to these proteins could mask as their Fe(III) counterparts. In a Trojan Horse fashion, the Ti(IV) protein compounds could attack bacteria that have evolved molecular mechanisms to steal Fe(III) from these proteins from their hosts.

5. Intracellular iron inhibition by Ti(IV)

In plants, Ti(IV) exhibits properties that are specific to it and also those that are proposed to be synergistic with those of Fe(III) [8]. At high concentrations though Ti(IV) behaves antagonistically toward Fe(III) by potentially competing with Fe(III) for biomolecular binding and inhibiting the function of the metal. This antagonistic behavior could result in phytotoxicity [8]. In the human body, Ti(IV) is also expected to exhibit this behavior when it exceeds concentrations levels in blood that sTf and citrate are unable to regulate. In solution studies with sTf and lactoferrin, high concentrations of Ti(IV) reduce Fe(III) binding [73, 166]. Ti(citrate)3 added to human blood serum completely saturated sTf with Ti(IV) and in the process displaced all bound Fe(III) [167]. Hydrolyzed Ti2-sTf-(CO3)2 at twenty times greater concentration than Fe2-sTf-(CO3)2 inhibited 60% Fe(III) uptake into BeWo human placental cancer cells [23]. At the typical serum concentrations of Ti(IV), an antagonistic behavior toward Fe(III) would not take place because it is ~100 times less available. However, localized high concentrations of labile ‘ionic’ Ti(IV) released from implants could affect Fe accessibility in cells and tissues and be the source of some of the health problems associated with implant failure [121, 168].

Insight into how Ti(IV), outside of the blood regulation imposed by the synergistic behavior of sTf and citrate, can exhibit in cells is provided by Ti(IV) compounds developed with the family of Fe(III) chelators called chemical transferrin mimetic ligands. The Ti(IV) compounds made with the cTfm ligands HBED and deferasirox (Fig. 7) exhibit potent cytotoxicity and directly affect iron bioavailability in cells [26, 68, 69, 87]. These compounds, because of their very high solution stability, bypass any interaction with citrate and sTf and even serum albumin. They are believed to operate, in part, by releasing Ti(IV) in cells to sequester Fe(III) from the labile pool via transmetallation. Kinetics studies examining the rate of transmetallation between the Ti(IV) cTfm compounds and a labile Fe(III) source, Fe(III) citrate, demonstrate exchange initiating soon after solution mixing. This transmetallation does not occur with Fe(III)-bound sTf, the dominant form of Fe(III) in blood, which indicates the exclusivity of this process within cells. The cytotoxic potency of the metal-free chelators is weaker (IC50 values in the 12 to >100 µM range) than the Ti(IV) compounds (IC50 values in the 6–25 µM range) suggesting that the Ti(IV) ion plays a major role. The intracellular sites of attack for the Ti(IV) released from these compounds are yet unknown. Cells pretreated with Fe(III) citrate are more viable in the presence of the Ti(IV) cTfm compounds [68, 145].

A recent electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) study provides more details surrounding the molecular mechanism of Fe(III) bioavailability inhibition [169]. Whole-cell EPR studies could be used to track any inhibition of the Fe-containing ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) within cells, the only enzyme our cells use to produce deoxyribonucleotides that serve as the building blocks for DNA synthesis [170–172]. Human RNR consists of a quaternary structure made of dimeric alpha and dimeric beta subunits. The alpha subunits (R1) contain the active site and the beta subunits (R2) contain a diiron cofactor site (Fig. 10a). The enzyme becomes activated following the binding of two Fe(II) ions at the cofactor site and oxidation of the metal to Fe(III) upon reaction with O2. The oxidation step results in the formation of an important tyrosyl radical located near the diiron site which travels to the active site to initiate the radical-based catalysis. The active form of the enzyme can be gauged using EPR due to the tyrosyl radical producing a g ~ 2 signal [173, 174]. The g ~ 2 signal is attenuated for Jurkat cells treated with the Ti(IV) cTfm compounds and the metal-free cTfm ligands compared to control cells (Fig. 10b). This indicates that treated cells have significantly less active RNR due to less available Fe to activate it. Even though Fe(II) is the dominant oxidation for iron species within cells (~80%), it exists in dynamic equilibrium with the Fe(III) available and any decrease in the labile Fe(III) pool would decrease the Fe(II) pool. Chelation of Fe(III) by HBED and deferasirox would transform the Fe into an inert species. EPR was also used to look at any changes in the intracellular iron pool. No changes in the low spin Fe(III) pool (g ~ 2.1) [174] could be detected for the Ti(IV) compounds or the metal-free ligands. In the high spin Fe(III) region (g ~ 4.31) both Ti(IV) HBED and metal-free HBED increase the population of high spin Fe(III) species but the deferasirox compounds do not [169]. This study reveals different changes in the intracellular Fe speciation induced by the cTfm compounds that need further examination but nonetheless ultimately impact the activity of RNR. Whether Ti(IV) can directly bind at the diiron site of RNR and serve as a direct inhibitor of Fe binding and RNR activation warrants investigation. The inhibition of Fe bioavailability may be responsible for the apoptotic cell death triggered by the cTfm compounds [69]. It is impressive that with the amount of endogenous Ti(IV) in the body that these cytotoxic behaviors are not observed. This suggests that there must be intracellular molecular mechanisms that exist to regulate the localization and bioactivity of Ti(IV).

Fig. 10.

Whole-cell electron paramagnetic resonance study of the effect of Ti(IV) cTfm compounds and the metal-free cTfm ligands on the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) enzyme of Jurkat cells. For this study, Ti(IV) compounds of HBED and deferasirox and also the metal-free ligands were used. a. The diiron site of the beta subunits of RNR contains a stable tyrosyl radical (g ~2) indicative of active enzyme. This figure was modeled based on the E. coli structure (PDB entry 4ERM). b. The g~2 signal associated with the RNR tyrosyl radical of Jurkat cells treated and untreated with the cTf compounds and also the metal-free ligands. c. The g~4.31 signal associated with the high spin Fe(III) pool of Jurkat cells treated and untreated with the cTf compounds and also the metal-free ligands.

6. Conclusion

While Ti(IV) may be nonessential to humans, evidence strongly points to its bioactivity in the body and potential function. From its entry in the body to its transport in blood and into cells, there exists a strong communication between the lmw and hmw biomolecular pools to regulate Ti(IV). Many of the same key players from these pools also regulate Fe(III) and facilitate both its immediate use and storage for future use. This review has explored the exclusivity of Ti(IV) binding to the Fe(III) transport protein sTf and the pathway(s) following this interaction (Fig. 11) that lead to its high organelle bioaccumulation without inhibiting Fe-dependent processes and causing toxicity. STf is responsible, in synergism with citrate, for the uptake of labile ‘ionic’ titanium released into blood, protecting it from precipitation but also protecting us from the cytotoxic behavior that it can exhibit depending on its ligand coordination. Serum albumin, to a lesser extent, also has a role in these processes. Careful delivery of Ti(IV) into cells and release into the cytoplasm is very likely to produce a labile Ti pool with the capacity to exhibit functions comparable to those of Fe. Bioactivity specific to Ti(IV) is sure to be the consequence of differences between the aqueous coordination chemistry of Fe(III) and Ti(IV). Proposed functions for Ti include facilitating acid/base catalysis and phosphorylation, playing a structural role in the phosphoproteome or other phosphate containing molecules, contributing to the growth and development of babies/young children, and serving as an antibacterial agent. Work with Ti(IV) cTfm compounds reveals that Ti(IV) in interaction with iron chelators can inhibit the bioavailability of the labile iron pool and inactivate important biochemical processes that keep cells alive. That this example of toxicity has not been detected in the human body suggests that intracellular molecular mechanisms exist to control the trafficking of Ti. Emerging chemical biological tools and techniques to monitor the difficult to track metal [145] will help to unlock these mechanisms and provide further insight into the bioinorganic chemistry of Ti in humans and other living organisms.

Fig. 11.

The proposed mechanism of sTf mediated cellular delivery of Ti from Ti-implants and its low molecular weight (LMW) compounds as regulated by citrate. Citrate binds labile ionic ‘Ti(IV)’ released from implants or from LMW compounds that enter the bloodstream and then delivers the Ti(IV) to sTf. Ti(IV)-bound sTf is recognized by the transferrin receptor (TfR), which transports the metal into the cell via endocytosis. Partially bound Ti(IV) or mixed Fe(III)/Ti(IV) sTf species may be involved in the delivery of Ti(IV) into cells. A combination of pH reduction and/or sequestration by a chelator (L) removes Ti(IV) from sTf. The Ti(IV) as a titanyl ion or as a complex is released from the endosome either by a transporter or passive diffusion and forms a proposed labile Ti(IV) pool (even if transiently). It is currently unknown whether Ti is trafficked for storage and utilization within mammalian cells. Adapted with permission from Journal of American Chemical Society, Vol. 138, Unusual synergism of transferrin and citrate in the regulation of Ti(IV) speciation, transport, and toxicity, 5659–5665, Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Highlights.

Ti(IV) similarity to Fe(III) hints towards its function and storage in humans

Ti(IV) can inhibit intracellular Fe bioavailability and function

Properties of in vitro ligands of Ti important in identifying in vivo ligands

Redox, structural, growth, and antibacterial functions proposed for Ti

Better tools are needed to decipher the in vivo fate of Ti(IV)

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory of Prof. José M. Rivera and the Molecular Science Research Center of the University of Puerto Rico Río Piedras for providing us with writing space. We also thank Daniel García Rojas for his help with information for the manuscript. M.S., S.A.L-R., K.G., S.S. and A.D.T. are supported by the NIH SC1 (5SC1CA190504) provided by the NIGMS and NCI. A.D.T. is also supported by funding from the Puerto Rico Science, Technology, and Research Trust (Agreement No. 2013-000019), the University of Puerto Rico FIPI Grant from the office of the DEGI, the University of Puerto Rico Score Stabilization Grant, and the Department of Chemistry at UPR RP. S.C.P.O. is supported by funding from the PR-INBRE Undergraduate Junior Research Associates Award. The time and effort devoted to this work is dedicated to all victims and survivors of the 2017 hurricane season.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ATCUN, amino terminus copper and nickel; CDCA1, cadmium-containing carbonic anhydrases; EELS, electron energy loss spectroscopoy; EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance; ESI, electron spectroscopic imaging; EXAFS, extended x-ray absorption fine structure, FBP, ferric binding protein; GGH, GlyGlyHis; HBED, N,N'-di(o-hydroxybenzyl)-ethylenediamine-N,N'-diacetic acid; hmw, high molecular weight; HSA, human serum albumin; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; LMCT, ligand to metal charge transfer; lmw, low molecular weight; N. gonorrhoeae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; nicaTf, nicatransferrin; nitrilotriacetic acid, NTA; PET, positron emission tomography; PDB, protein database; RNR, ribonucleotide reductase; SAXS, small-angle x-ray scattering; STEM, scanning transmission electron microscopy; sTf, serum transferrin; TfR1, transferrin receptor 1; XRF, x-ray fluorescence.

References

- 1.Oshida Y. Bioscience and Bioengineering of Titanium Materials. Elsevier Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarselli MA. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:546–546. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. 3. Elsevier Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair M, Elizabeth E. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015;15:939–955. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2015.9771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvajal M, Alcaraz CF. J. Plant Nutr. 1998;21:655–664. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruby M, Cigler P, Kuzel S. J. Plant Nutr. 2002;25:577–598. [Google Scholar]