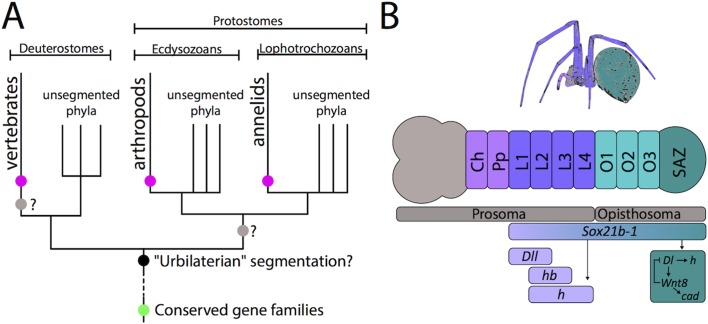

Figure 1. The evolution of segmentation.

(A) Schematic representation of the phylogenetic relationships of bilaterians (adapted from Peel and Akam, 2003). Although vertebrates, arthropods, and annelids all have a segmented anterior-posterior body axis (pink dots), they are all closely related to phyla that are not segmented. Some conserved gene families (including Sox and Wnt) were already present before the emergence of the bilaterians (green dot) and are involved in many important developmental processes: some are also known to be involved in segmentation in various animals. However, the evolution of segmentation is still under debate. It could have evolved once in the 'urbilateria' (black dot), the last common ancestor of all bilaterians, or twice – at the base of the vertebrates and independently at the base of the protostomes (grey dots). Both of these scenarios would suggest a subsequent loss of segmentation in all closely related unsegmented phyla. The third scenario is that segmentation independently evolved three times – at the base of the vertebrates, arthropods, and annelids (pink dots). (B) Schematic representation of the germband and related adult tissues of the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum (adapted from Paese et al., 2018). The body of a spider embryo is comprised of the prosoma (including the head (grey) and thorax (violet and indigo) and the opisthsoma (green). The formation of the leg-bearing prosomal segments (L1–L4) depends on the gap-like functions of genes such as Distal-less (Dll), hairy (h), hunchback (hb) and, as now shown by Paese et al., Sox21b-1. The opisthosomal segments are added sequentially by a segment addition zone (SAZ, dark green) controlled by a complex gene regulatory network (dark green box), probably induced by Sox21b-1, that contains caudal (cad) and components of the Wnt (Wnt8) and Notch (Delta) signaling pathways. Ch: Cheliceral segment. Pp: Pedipalpal segment. Dl: Delta.