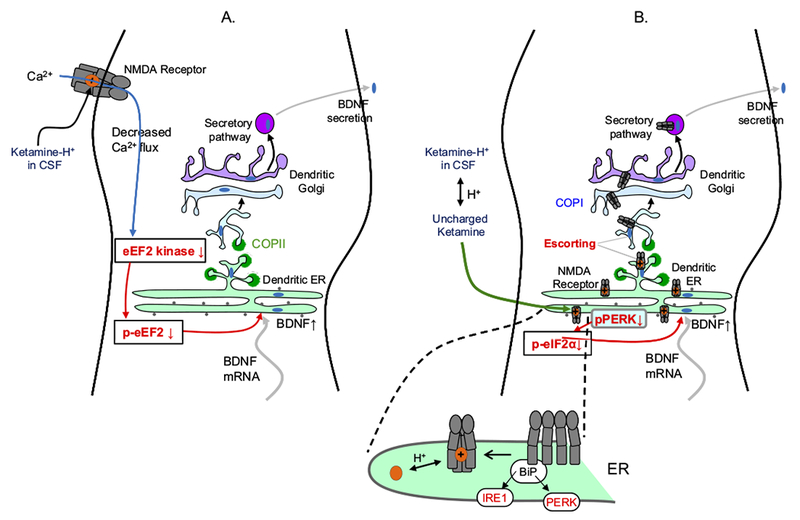

Figure 3.

Diagrams of a dendrite, showing possible explanations for the 1- to 2-hour delay before antidepressant actions of ketamine and related N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockers. Ketamine exerts at least some of these antidepressant effects via increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) secretion (76,77,94,95), and we therefore diagram mechanisms leading to BDNF secretion. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor secretion presumably requires depolarization, which may explain the requirement for 2-amino-3-(5-methyl-3-oxo-1,2-oxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid (AMPA) receptor activation (82). Note that dendritic endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi are thought to be simpler than the somatically located organelles shown in previous figures. The selective NMDA receptor 2B antagonist Ro 25-6981 had similar effects to ketamine (77). The transcription of BDNF is not required (as shown by insensitivity to actinomycin D), but its synthesis is required (as shown by sensitivity to anisomycin). In hippocampus, ketamine and NMDA, in the absence of neuronal activity, led to dephosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor (eEF2) (also called calcium/calmodulin-dependent eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase), but only ketamine produced this effect in cortex. Rottlerin and NH125, which inhibit several kinases including eEF2 kinase, also had BDNF-dependent antidepressant activity. (A) An outside-in mechanism, downstream from NMDA receptor block. Ketamine binds within the NMDA receptor pore but does not enter the neuron. The data have generally been interpreted in light of the knowledge that ketamine blocks spontaneous miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents through NMDA receptors (76). It is implied that decreased Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors begins the transduction pathway leading to effects on presynaptic or postsynaptic efficiency. (B) Possible inside-out mechanisms, resulting from intracellular binding to nascent NMDA receptors. Existing data show that ligands can act as pharmacological chaperones for glutamate receptors within the ER (96), analogous to experiments in which nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Two possible sequelae could lead to increased BDNF secretion. First, enhanced ER exit would decrease ER stress, for instance by decreasing phosphorylated protein kinase R-like ER-localized eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase (pPERK). This would decrease phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α), increasing synthesis of ER proteins, including BDNF, thus producing the observed BDNF increase. Activation of NMDA receptors increases ER stress markers such as eIF2α phosphorylation and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (97). However, it is not known whether blockade of NMDA receptors by ketamine has any effect on eIF2α phosphorylation in the absence of ER stress. This would be a key test of the chaperoning-ER stress hypothesis. Blockade by MK-801 did decrease caspase-12 activation, even in the absence of ER stress; however, caspase-12 activation may occur in a pathway distinct from ER stress (98). Second, an escort effect of intracellular ketamine-NMDA receptor binding arises from the fact that both NMDA receptors and BDNF are trafficked via a nonstandard ER and Golgi vesicle pathway involving synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97) and calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase (CASK) (99,100). Additional knowledge about the synapse-associated protein 97-calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase trafficking pathway is crucial for evaluating the escort hypothesis. Chaperoning and/or matchmaking would occur in the ER. Escorting would occur when both the NMDA receptor and BDNF bind to Sec24 or at a later step. BiP, immunoglobulin binding protein; COPI and COPII, vesicle coat protein I and II complex; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; mRNA, messenger RNA; p-eEF2, phosphorylated eukaryotic elongation factor.