Abstract

African swine fever (ASF) is a viral disease that affects members of the Suidae family such as African bush pigs, warthogs, but also domestic pigs, and wild boar. It is transmitted by direct contact of naïve with infected animals, by soft ticks of the Ornithodoros genus, or indirectly by movement of infected animals, improper disposal of contaminated animal products or other sources related to human activity. The recent spread of ASF into Eastern and Central European countries is currently threatening the European pig industry. The situation is aggravated as to-date no efficient vaccine is available. African swine fever virus (ASFV) is a large enveloped ds DNA-virus encoding at least 150 open reading frames. Many of the deduced gene products have not been described, less functionally characterized. We have analysed ASFV protein expression in three susceptible mammalian cell lines representing a susceptible host (wild boar) and two non-susceptible species (human and green monkey) by mass spectrometry and provide first evidence for the expression of 23 so far uncharacterized ASFV ORFs. Expression levels of several newly identified ASFV proteins were remarkably high indicating importance in the viral replication cycle. Moreover, expression profiles of ASFV proteins in the three cell lines differed markedly.

Introduction

In the past decades, African swine fever (ASF) has repeatedly been introduced from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe. The most recent introduction in 2007 had its origin in Eastern Africa and started in Georgia by improper disposal of contaminated food in the vicinity of Poti harbour1 from where it spread across the Caucasus and the Russian Federation to reach the eastern border of the European Union in early 2014. The virus is now enzootic in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland and has spread to other European countries, e.g. the Czech Republic and Romania as well. The westward expansion of the disease is a serious threat to the pig industry in central and western European countries2,3. In spite of this increasingly threatening situation and many efforts, no effective vaccine has been developed to-date4.

African swine fever virus (ASFV), the causative agent of African swine fever, is the only member of the family Asfarviridae in the nucleocytoplasmic large DNA virus superfamily5,6. In different isolates, the size of the double-stranded DNA genome ranges from 170 kbp to 190 kbp, and contains over 150 predicted open reading frames (ORFs). In addition to the proteins that are required for basic viral functions like replication and morphogenesis, numerous ASFV proteins modulate cellular pathways like apoptosis or innate immunity, accounting for the high complexity of virus-host interactions7. The fact that ASFV can replicate in swine as well as in its arthropod vector, soft ticks of the Ornithodoros genus, may contribute to the complexity of ASFV protein expression. In addition to the 54 structural proteins that form the complex ASF virion8, a number of non-structural proteins are also encoded. However, many of them are completely uncharacterized and lack any evidence for expression in cell culture or in infected animals. They frequently belong to multi gene families (MGF) which are known to influence cell tropism and host range of ASFV9–11.

The intent of this study was to identify the intracellular proteome of ASFV, to provide a comprehensive catalogue of ASFV proteins expressed in mammalian cell culture and to identify a core set of ASFV proteins required to support infection of permissive cultured mammalian cells, but also to elucidate potential host-specific differences in the expression profiles. Since immunologic reagents for specific detection are lacking for most ASFV proteins, we have applied mass spectrometry (MS) which, as an ‘open-view’ tool, allows the detection of proteins by identification of peptides deduced from the viral genomic sequence. A GFP-expressing thymidine kinase (TK) negative recombinant of ASFV strain OURT 88/3 (OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP) was used for infection. OURT 88/3 is a naturally attenuated non-hemadsorbing field strain isolated from Ornithodoros erraticus ticks in Portugal12 which is considered for use as vaccine as it has shown the ability to protect pigs against a challenge with virulent ASFV strain OURT 88/112–14. Three susceptible cell lines were selected for proteome analysis after infection. WSL-HP is a lung cell line from wild boar, a natural host of ASVF, while HEK 293 cells originate from humans which are not susceptible to infection. Vero cells were included, since they have been extensively used for infection experiments with ASFV in the past.

Results and Discussion

MS study design

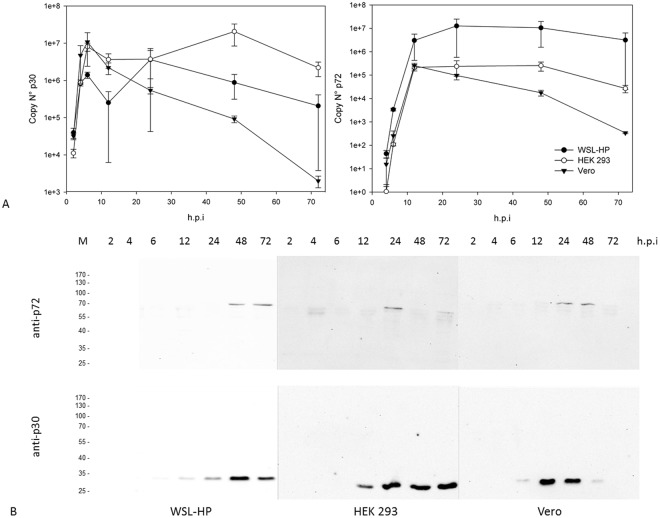

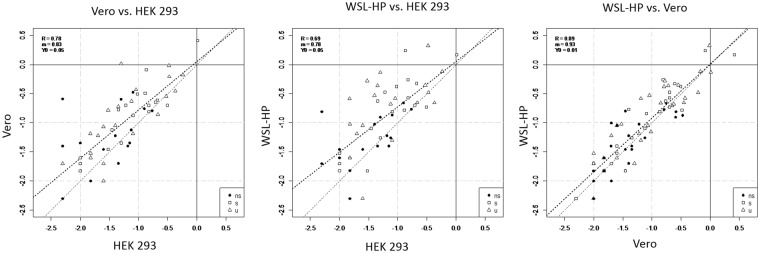

The three cell lines used in this study were fully susceptible to infection with the recombinant ASFV OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP expressing GFP under the control of the late ASFV p72 promotor15–17. As shown in Fig. 1 the virus replicated in all three cell lines, although final titers on Vero and HEK 293 were 20-fold and 16-fold lower than on WSL-HP cells, respectively. Before preparing samples for the MS analysis the infection conditions were adjusted to ensure that completely infected cell monolayers were used for the preparation of the protein extracts in order to achieve high sensitivity for the detection of ASFV proteins and to enable the MS based quantitative comparison of ASFV protein expression between the different cells. Cell monolayers were inoculated with ASFV OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP and GFP fluorescence, indicating the entry into the late phase of infection, was monitored over time. After 24 h (HEK 293 and Vero) and after 48 h (WSL-HP) the cell monolayers were entirely positive for GFP fluorescence. Immunoblot and RT-qPCR analyses targeting structural proteins p30, expressed with early kinetics18,19, and p72, expressed with late kinetics15,16, confirmed that the cell lines were in the late phase of infection (Fig. 2) at the given time points which were then chosen to harvest the cells for the MS analysis.

Figure 1.

ASFV OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP productively infects WSL-HP, Vero, and HEK 293 cells. After inoculation of WSL-HP, Vero, and HEK 293 cells with OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP, supernatants were collected at the times indicated and titers of the progeny virus were determined on WSL-HP cells. The in-vitro growth kinetics show that ASFV OURT 88/3-dTK-GFP replicates well on all three cell lines, although final titers on Vero and HEK 293 cells are over tenfold lower than on WSL-HP cells.

Figure 2.

In-vitro expression kinetics of OURT 88/3 proteins p30 and p72. Cells were infected with ASFV OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP and harvested at the times indicated. Panel A shows the quantitation of the p30 (left) and p72 (right) expression by RT-qPCR and panel B an immunoblot analysis, respectively. p30 is expressed with early, p72 with late kinetics, time points are given in hours after infection (h.p.i.). The means of 2 independent experiments are shown. At the time of harvest for MS, p72 is expressed in all three cell lines.

For the proteome analysis of the cell extracts a shotgun approach was applied using a mass spectrometric platform combining nano liquid chromatography (nLC) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation tandem time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) MS. In short, total protein extracts of the three cell lines were prepared at the designated time points, proteins were digested into peptides, separated by nLC and analysed on the MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument. The protein composition of the extracts was then determined by a query of the spectra using a sequence database containing host and virus proteins. To increase sensitivity and improve sequence coverages of ASFV proteins in the mass spectrometric analysis, two replicates of each of the three infected cell lines were digested with three different proteases with complementary specificity (trypsin, chymotrypsin and Glu-C). The choice of the proteases based on an in-silico comparison of the physical properties (molecular weight, isoelectric point, pI, and the Grand Average of Hydropathy, GRAVY20) of ASFV and Sus scrofa proteins which had indicated that the viral proteins were, on average, smaller (37.7 kDa vs.50.5 kDa), more basic (pI 7.81 vs. 7.33), and more hydrophobic (GRAVY −0.21 vs. −031) than the Sus scrofa proteins (Supplementary Fig. S1). The results of the six nLC-MALDI-TOF/TOF MS runs for every cell line were compiled into a single result file for the calculation of the identification scores, sequence coverages and the number of peptides identified in every protein. A comprehensive representation of the MS data is provided as Supplementary data, Tables S1 and S2.

Classification of ASFV proteins into structural, non-structural and uncharacterized proteins followed a recent review6. Additionally, the literature was searched for any evidence for the expression of ASFV RNAs or proteins and the references were added to the column ‘Ref’ in Supplementary Table S3. To the best of our knowledge, we demonstrate the existence of 23 ASFV proteins, for which no evidence of expression was available so far.

Qualitative proteome analysis

The results of the qualitative MS analyses are summarized in Fig. 3. In total, for 94 of the 157 OURT 88/3 ORFs the corresponding proteins could be identified. Thirty-seven of these identifications confirm known proteins and for further 34 evidence for transcription, but not for the existence of the corresponding protein, can be found in the literature. These include 6 out of the 32 members of the MGF genes present in OURT 88/3. For 23 of the identified proteins we have not found any evidence for expression of the corresponding gene in the current literature, neither for the presence of a transcript, nor of a protein. The detailed results obtained for all 94 identified ASFV proteins in the three different cell lines are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

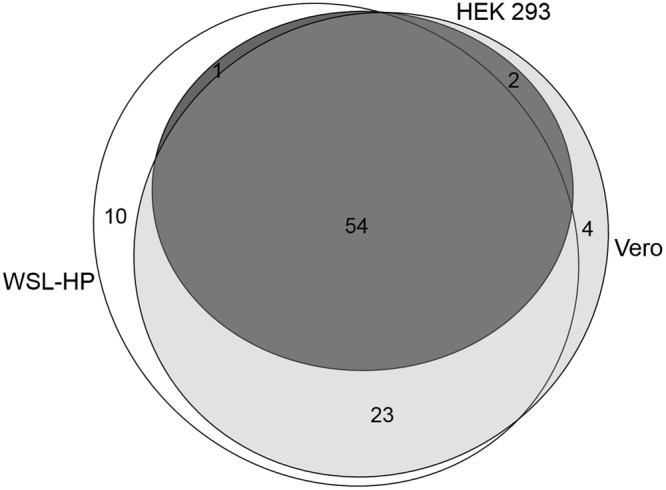

Figure 3.

Comparison of the ASFV proteins expressed in WSL-HP, HEK 293 and Vero cells. In total, 94 ASFV proteins were identified by MS, 54 of them in all three cell lines. Of the remaining 40, 23 were shared by Vero (light grey) and WSL-HP (white). Ten, and four proteins were exclusively expressed in WSL-HP and in Vero cells, respectively.

Expression profiles of ASFV specific proteins differed markedly between the cell lines (Fig. 3). Fifty-four proteins were detected in all three cells which may represent a core set of ASFV proteins required to maintain the late phase of infection mammalian cell cultures. Ten proteins were exclusively detected in WSL-HP cells, while 4 more were exclusively identified in Vero cells. Twenty-three proteins were shared between WSL-HP and Vero cells but were undetectable in HEK 293 cells.

The observed differences were obviously not due to technical issues, as the low number of 57 identified viral proteins in HEK 293 cells was in contrast to the high number of 1,251 identified host cell proteins (vs. 1,194 in Vero and 969 in WSL-HP) and may reflect a limitation in the replication of ASFV in cells from the non-susceptible human species. Another factor contributing to the observed differential expression of ASFV proteins could be the different growth kinetics of OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP in the cells from different hosts (Fig. 1) which may have influenced expression profiles in the late phase. Also, proteins exclusively expressed in the early phase of infection may be underrepresented. In early studies using one-dimensional or two-dimensional electrophoresis (2DE) in combination with radioactive pulse labelling and inhibitors of viral DNA replication21–24 the numbers of virus induced proteins synthesized in the early and late phases of infection were assessed. Although the experimental conditions were different from ours, it is interesting to note that in the study by Esteves et al.23, 24 of the 35 early proteins and in the study by Urzainqui et al.21 all early proteins were also transcribed in the late phase. As these numbers are based on the incorporation of radioactive precursors in a pulse labelling experiment we assume that the majority of early proteins will be amenable to mass spectrometric detection also in the late phase of infection as they are still synthesized or have accumulated during infection. Indeed, a number of proteins listed in Supplementary Table S3 are expressed with early kinetics. In contrast to these early publications, MALDI-TOF MS was combined with 2DE analysis in a study focusing on the identification of host proteins modulated after ASFV infection25. Approximately 60% of the 68 identified protein spots were of viral origin, but the identities of these proteins and kinetics of expression were not reported.

For the qualitative analysis the use of two more proteases in addition to the most commonly used enzyme, trypsin, was beneficial for the yields and the sequence coverages of identified proteins. This observation was most striking for the comparison of tryptic and chymotryptic peptides obtained after digestion of infected WSL-HP cells. While only 31.9% of the 8,643 Sus scrofa specific peptides resulted from the chymotrypsin cleavage, this was the case for 44.7% of the 1,254 ASFV specific peptides. Using Fisher’s exact test, these ratios indicated a highly significant overrepresentation of chymotryptic peptides among the ASFV derived peptides. Most likely, this was a consequence of the slightly divergent physicochemical properties of ASFV proteins in comparison to the host proteins.

A prerequisite for MS based proteome analysis is the correct annotation of the ORFs within the genome sequence. We have therefore also applied a proteogenomic approach to our MS data in order to identify any additional unidentified ORFs. To this end, the genome of ASFV strain OURT 88/3 was translated in the six possible reading frames and the resulting database was used to re-evaluate the mass spectra with the Mascot search engine (data not shown). However, peptide assignments to so-far unknown potential new reading frames were not observed so that we have no indication for any additions to the annotations in the published OURT 88/3 protein sequences.

Of the 32 members of the multi gene families present in OURT 88/3, we have identified 6, specifically one MGF 505 protein (MGF 505-9 R) and five MGF 110 members (MGF 110-1L, -2L, -4L, -5L, and -14L). While MGF 110-14L and MGF 505-9 R were expressed weakly and detected only in Vero cells, the expression of the four remaining MGF 110 proteins (1L, 2L, 4L, and 5L) was stronger and, with the exception of MGF 110-2 L, they were detected in all three cell lines. While MGF 360 and MGF 530 members have been reported to be virulence determinants, interact with the innate immune system9,26,27, and determine the host range of ASFV10,11, MGF 110 genes have been shown to be non-essential for the infection of and virulence in pigs28. Nevertheless, MGF 110-1L, -4L and -5L are expressed in all three cell cultures suggesting they may play an at least beneficial role here. As MGF 110 proteins have been reported to contain signal peptides29, the coding sequences were analysed for this feature by SignalP 4.030 and Phobius softwares31,32. Twelve predicted mature sequences were added to the sequence database for a re-evaluation of the mass spectrometric data. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, the N-termini of the predicted mature sequences of all four identified MFG 110 proteins 1L, 2L, 4L, and 5L and also of pI329L were confirmed by MS. For 44 additional of the 94 identified proteins the N-terminal peptides were identified (Supplementary data, Table S1). Only six were in the native amino form, while all other were modified by N-terminal acetylation, a common post-translational modification.

Quantitative proteome analysis

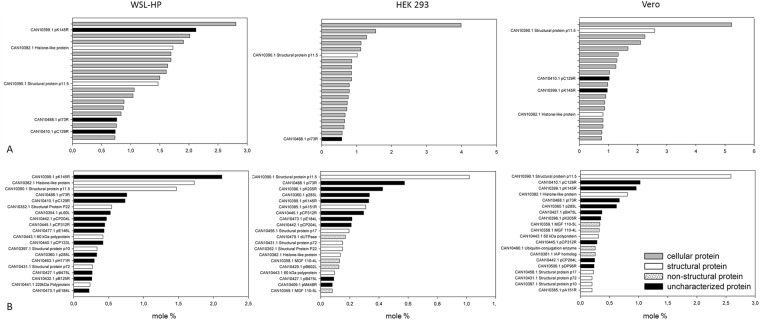

The quantitative evaluation of the MS analysis shown in Figs 4 and 5 was performed using the exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI)33, a label-free approach which allows the calculation of protein abundances on basis of the number of identified peptides that are annotated to a certain protein during the protein identification process. With 14 and 17 mole % (10.2 and 13.3 weight %) of total protein content the expression of ASFV proteins in Vero and WSL-HP was quite massive and significantly higher than in HEK 293 cells (6.3 mole %, 4.8 weight %). The lower number of identified ASFV specific proteins in HEK 293 cells correlated with the lower content of ASFV proteins present in this cell line and could therefore be a matter of sensitivity as poorly expressed proteins may have dropped below the detection limit. However, the quantitative evaluation of the MS data showed that some ASFV proteins were expressed in HEK 293 cells at similar or even higher levels than in WSL-HP or Vero cells (Fig. 4) indicating that expression of individual proteins differed markedly in the different cells and arguing against a general underrepresentation of ASFV proteins in HEK 293 cells.

Figure 4.

Correlation of ASFV protein expression levels in WSL-HP, HEK 293 and Vero cells. Protein abundances determined in the cells indicated at the axes are given in mole % in a logarithmic scale. Non-structural (ns) proteins are marked as full black circles, structural (s) and uncharacterized (u) proteins as open squares and triangles, respectively. Correlation coefficients are given as R, the y-intercepts and slopes of the dotted regression lines are given as Y0 and m, respectively. Dissecting lines are dashed.

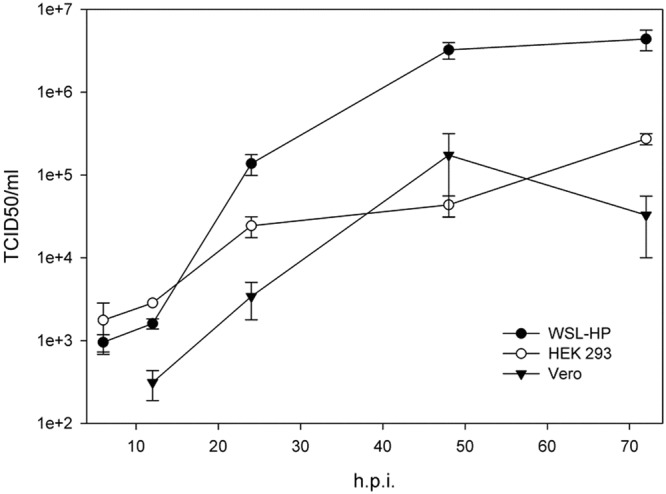

Figure 5.

Comparison of the most abundantly expressed ASFV proteins. Protein proportions were calculated as mole percentages (x-axes) on basis of the tryptic digests using the emPAI algorithm. Panel A shows the 20 most abundant proteins (including cellular proteins as grey bars) and panel B the 20 most abundant ASFV proteins in decreasing order. Even in HEK 293 cells, which had the lowest overall content of ASFV proteins, two viral proteins were present among the 20 most abundant proteins. In all cell lines the structural protein p11.5 as well as the so far uncharacterized proteins pK145R and pI73R were expressed at high abundance. Note that in panel B, despite of some overlap between the top-ranking proteins in different cells, there are considerable differences in the abundances.

Although the abundances of individual ASFV proteins varied in the different cell lines, a certain degree of correlation between the expression levels was observed which was most striking for the ASFV proteins expressed in Vero and in WSL-HP cells (Fig. 4, right panel) representing a susceptible (WSL-HP) and a non-susceptible (Vero) host. This result suggests that the course of infection in both cell lines is similar and both may be useful for infection studies with ASFV. This observation may also be helpful for the retrospective assessment of studies which have been performed with Vero cells in the past.

Non-structural proteins were found among the less expressed proteins in all three cell lines while the most abundant were structural proteins and, surprisingly, so far uncharacterized proteins. In Fig. 5, an overview of the 20 most abundant proteins in the cell extracts (including host proteins) is given in panel A and the abundances of the 20 highest ranking ASFV proteins (without cellular proteins) are compared in panel B. The abundance ranking within the ASFV proteins differed between in the three cell lines (Fig. 5B) which may reflect different relevance of the proteins in cells of the three differentially susceptible hosts. However, there also were notable similarities. Three so far uncharacterized proteins ranked among the top 20 abundant proteins in WSL-HP cells, namely pK145R, pC129R, and pI73R. Of these, pK145R and pC129R ranked also among the top 20 most abundant ASFV proteins in Vero cells. The third, pI73R, was also abundantly expressed in HEK 293 cells. The high expression levels of these proteins in all three tested cell lines may indicate important roles during ASFV infection and make them prime subjects of future investigations including rational vaccine design.

Methods

Virus and cells

HEK 293 (CCLV-RIE #197)34, WSL-HP (CCLV-RIE #1346)35, and Vero cells (CCLV-RIE #0015) were provided by the Biobank of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut. Cells were cultivated in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%) and Penicillin/Streptomycin solution (1%, Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 2.5% CO2. All live-virus experiments were carried out in a biocontainment facility that fulfils the safety requirements for ASF laboratories and animal facilities laid out in Chapter VIII of Commission Decision 2003/422/EC. The GFP-expressing ASFV mutant OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP was used throughout this study. OURT 88/3-ΔTK-GFP was generated from strain OURT 88/3 (kindly provided by Linda Dixon, Pirbright, UK) as described for the corresponding NHV recombinant17. The correct integration of the late ASFV p72 promoter regulated GFP expression cassette was confirmed by direct sequencing of PCR amplicons spanning the mutagenized locus. To improve infection rates, the cells were inoculated in 6-well or 24-well plates by centrifugation (600 × g at 37 °C) during the 1 h incubation period (JH Forth, L Käbisch, R Portugal, S Blome, GM Keil, unpublished). The inoculum was then replaced by fresh medium and cells were further incubated.

For measuring growth kinetics cells were cultivated in 24-well plates and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2. After incubation for the times indicated supernatants were removed and cells were scraped into phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 250 µl), and stored at −80 °C. Progeny viral titers were determined on WSL-HP cells cultivated in 96-well plates (Eppendorf, # 0030 730.119) using serial tenfold dilutions and the method of Reed and Muench36. For quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblots, cell monolayers were washed with PBS and harvested in Trizol ReagentTM (Invitrogen, #15596-026).

For the MS analyses, HEK 293, WSL-HP, and Vero cells were cultivated in 6-well cell culture dishes (Corning, #3506) to 90% confluency. After infection at a MOI of 2 (HEK 293) or 5 (Vero and WSL-HP) and further incubation for 24 h (HEK 293 and Vero cells) or 48 hours (WSL-HP cells) the complete cell layer was positive for GFP fluorescence. The cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, scraped into lysis buffer (500 µl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M DTT, 2% SDS)37 and heated to 95 °C for 10 min. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 5 min, RT), and aliquots containing extracts equivalent to 2 × 105 cells were processed for MS.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For RNA-extraction, cells were harvested in Trizol ReagentTM (250 µl, Invitrogen). After addition of dichloromethane (50 µl), samples were centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min), the aqueous phase was removed and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, #74104) and RNase free DNase-Kit (Qiagen, # 79254). For removal of residual DNA, samples were treated with Turbo DNase (Life Technologies, #AM2238). Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) targeting p30 and p72 was performed using standard protocols (JH Forth, L Käbisch, R Portugal, S Blome, GM Keil, unpublished).

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Samples of cell lysates containing the equivalent of 1.5 × 104 cells (approximately 15 µg protein) were mixed with sample buffer38, heated to 95 °C for 10 min, and separated by electrophoresis in a Mini Protean II apparatus (BioRad) using hand cast gradient (7–15% acrylamide) or homogenous (10% acrylamide) SDS-polyacrylamide gels38. Proteins were visualized by colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining39.

Immunoblots

Proteins were purified using the Trizol Reagent workflow as described in the manual, separated on polyacrylamide gels (10%) and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane40. Blots were incubated with PBS containing 10% horse serum and 6% skimmed milk powder overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with appropriate dilutions of rabbit sera directed against p30 (1:20,000) or p72 (1:50,000) made up in blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 [PBS-T], 0.6% skimmed milk powder, and 1% horse serum) for 1 h at RT, the membranes were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.3% Tween-20 for 1 min and in PBS-T for 5 min and then incubated with secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution in PBS-T, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, Dianova, #111-036-045) for 1 h at RT. Membranes were washed as above, and bound antibodies were detected using the Clarity Western ECL substrate (BioRad, # 170-5061).

Mass spectrometric workflow

Proteome analysis was performed using a shotgun approach. Samples were digested into peptides, which were separated by nano liquid reversed phase chromatography (EASY-nLC II, Bruker), and spotted to a MALDI target by a Proteineer fcII sample spotting robot (Bruker). Mass spectrometric analysis was performed on an UltrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument (Bruker). All reagents used were of highest purity available, all solvents were of MS grade.

Protein digest

Proteins were digested by filter-aided sample preparation (FASP)41 using a Vivacon 500 filter unit (MWCO 30 kDa, Sartorius, #VN01H22) with slight adjustments of the buffer compositions for the three different proteases. Trypsin (Promega, #V5111) digest was carried out in NH4HCO3 buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.8), while endoproteinase Glu-C (V8 protease from Staphylococcus aureus, Promega, #V165A) and chymotrypsin (Promega, #V106A) digests were performed in Tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (Tris-HCl) buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5). Digest was carried out for 16 h at 37 °C (trypsin and Glu-C) or 25 °C (chymotrypsin) with enzyme:substrate ratios of 1:50. After filtration peptides were desalted with Ziptip C18 solid phase extraction tips (Merck Millipore, # ZTC18S960), dried under vacuum and dissolved in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution (0.1% v/v) to a concentration of 2 μg/μl prior to nano-LC.

Nano reversed phase liquid chromatography of peptides

Peptide samples equivalent to 10 µg protein42 were diluted in TFA (0.1%) and applied onto a NS-MP-10 loading/desalting column (C18-modified silica gel, 5 µm bead size, inner diameter 100 µm, length 20 mm, BioSphere). After washing with TFA (40 µl, 0.05%, 5 µl/min) peptides were eluted onto the analytical column (Acclaim PepMap100, 75 µm × 15 cm, C18, 3 µm, 100 Å; Thermo Scientific, #160321) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min by application of an acetonitrile (ACN) gradient with the following profile (solvent A: 0.05% TFA, solvent B: 90% ACN, 0.05% TFA): 2% to 9% solvent B (0–15 min), 9% to 32% solvent B (15–211 min), 32% to 45% solvent B (211–226 min) and 100% solvent B (226–238 min). Fractions were collected every 10 s. Eluted peptides were mixed with an α-cyano-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix solution (0.416 µl per fraction) made up as suggested by the manufacturer (Bruker).

MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometric analysis was performed in positive mode in the m/z range from 700 to 3,500 Da. A maximum of 40 peptide peaks per fraction with signal-to-noise ratios above 5 were selected for fragmentation. The spectra were processed with Flexanalysis software (version 3.4, Bruker) and the proteins were identified by the Mascot search engine (version 2.4.1, Matrix Science) using the following settings: peptide and fragment mass tolerance were set to 25 ppm and 0.7 Da, respectively. Oxidation of methionine and the acetylation of protein N-termini were set as variable modifications, whereas the carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as fixed modification. One missed cleavage site was tolerated for tryptic digests, up to 6 for samples digested with Glu-C or chymotrypsin. The false discovery rate was set to a maximum of 2%. For the Mascot search of samples from the different species databases representing the human and the domestic pig proteome were downloaded from the Ensembl repository43 while the Chlorocebus sabaeus proteome was downloaded from the Uniprot Knowledgebase44. Proteins specified by the used ASFV strain OURT 88/3 (GenBank AM712240.145), were added to all three host cell proteomes and the appropriate compilation of viral and host cell proteome was used for the different samples. The results of the Mascot database search were exported to the ProteinScape software (Version 3.1, Bruker). Only proteins identified with at least two peptides exceeding the Mascot peptide identification score are reported. Proteins were quantified using the exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI)46,47 on basis of the MS results of the tryptic digests.

Data evaluation

The following software was used for the construction of figures and Tables: CFX Manager (version. 3.1, BioRad), Aida Image Analyser (version 5.0, Raytest), Excel 2016 (Microsoft), SigmaPlot 11 (version 11, Systat) and the statistical programming language R48.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Linda Dixon for providing the OURT 88/3 strain, Dr. Sven Reiche and Matthias Lenk (Biobank of the FLI) for the cell lines, Dr. Walter Fuchs for the antiserum against p30 and Katrin Giesow for assistance with the immunoblot analysis.

Author Contributions

The concept of the study was designed by T.C.M., S.B., and A.K. C.K. and A.K. performed the MS analysis. Infection experiments with ASFV were done by C.K. and supervised by G.M.K. and S.B. RT-PCR experiments were designed by G.M.K. and carried out by C.K. and J.H.F. The figures were prepared by C.K. and A.K. The manuscript was written by C.K., T.C.M., S.B. and A.K.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-32985-z.

References

- 1.Rowlands RJ, et al. African swine fever virus isolate, Georgia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1870–1874. doi: 10.3201/eid1412.080591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penrith ML, Vosloo W, Jori F, Bastos AD. African swine fever virus eradication in Africa. Virus Res. 2013;173:228–246. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Cordon PJ, Montoya M, Reis AL, Dixon LK. African swine fever: A re-emerging viral disease threatening the global pig industry. Vet J. 2018;233:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias Marisa, de la Torre Ana, Dixon Linda, Gallardo Carmina, Jori Ferran, Laddomada Alberto, Martins Carlos, Parkhouse R. Michael, Revilla Yolanda, Rodriguez Fernando and Jose-Manuel, Sanchez-Vizcaino Approaches and Perspectives for Development of African Swine Fever Virus Vaccines. Vaccines. 2017;5(4):35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines5040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon, L. K. et al. InVirus Taxonomy Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (eds Andrew M. Q. King, Michael J. Adams, Eric B. Carstens, and Elliot J. Lefkowitz) 153–162 (Elsevier Academic Press, 2012).

- 6.Dixon LK, Chapman DA, Netherton CL, Upton C. African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res. 2013;173:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanez RJ, et al. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of African swine fever virus. Virology. 1995;208:249–278. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salas ML, Andres G. African swine fever virus morphogenesis. Virus Res. 2013;173:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neilan JG, et al. Novel swine virulence determinant in the left variable region of the African swine fever virus genome. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:3095–3104. doi: 10.1128/Jvi.76.7.3095-3104.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zsak L, et al. African swine fever virus multigene family 360 and 530 genes are novel macrophage host range determinants. J Virol. 2001;75:3066–3076. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3066-3076.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burrage TG, Lu Z, Neilan JG, Rock DL, Zsak L. African swine fever virus multigene family 360 genes affect virus replication and generalization of infection in Ornithodoros porcinus ticks. J Virol. 2004;78:2445–2453. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2445-2453.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boinas FS, Hutchings GH, Dixon LK, Wilkinson PJ. Characterization of pathogenic and non-pathogenic African swine fever virus isolates from Ornithodoros erraticus inhabiting pig premises in Portugal. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2177–2187. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez-Cordon PJ, et al. Different routes and doses influence protection in pigs immunised with the naturally attenuated African swine fever virus isolate OURT88/3. Antiviral Res. 2017;138:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulumba-Mfumu LK, Goatley LC, Saegerman C, Takamatsu HH, Dixon LK. Immunization of African Indigenous Pigs with Attenuated Genotype I African Swine Fever Virus OURT88/3 Induces Protection Against Challenge with Virulent Strains of Genotype I. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63:e323–327. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cistue C, Tabares E. Expression in vivo and in vitro of the major structural protein (VP73) of African swine fever virus. Arch Virol. 1992;123:111–124. doi: 10.1007/BF01317142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Escudero R, Andres G, Almazan F, Vinuela E. Inducible gene expression from African swine fever virus recombinants: analysis of the major capsid protein p72. J Virol. 1998;72:3185–3195. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3185-3195.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portugal R, Martins C, Keil GM. Novel approach for the generation of recombinant African swine fever virus from a field isolate using GFP expression and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine selection. J Virol Methods. 2012;183:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prados FJ, Vinuela E, Alcami A. Sequence and characterization of the major early phosphoprotein p32 of African swine fever virus. J Virol. 1993;67:2475–2485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2475-2485.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afonso CL, et al. Characterization of p30, a highly antigenic membrane and secreted protein of African swine fever virus. Virology. 1992;189:368–373. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urzainqui A, Tabares E, Carrasco L. Proteins synthesized in African swine fever virus-infected cells analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Virology. 1987;160:286–291. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escribano JM, Tabares E. Proteins specified by African swine fever virus: V. Identification of immediate early, early and late proteins. Arch Virol. 1987;92:221–232. doi: 10.1007/BF01317479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteves A, Marques MI, Costa JV. Two-dimensional analysis of African swine fever virus proteins and proteins induced in infected cells. Virology. 1986;152:192–206. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santaren JF, Vinuela E. African swine fever virus-induced polypeptides in Vero cells. Virus Res. 1986;5:391–405. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(86)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alfonso P, Rivera J, Hernaez B, Alonso C, Escribano JM. Identification of cellular proteins modified in response to African swine fever virus infection by proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4:2037–2046. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donnell V, et al. African swine fever virus Georgia isolate harboring deletions of 9GL and MGF360/505 genes is highly attenuated in swine but does not confer protection against parental virus challenge. Virus Res. 2016;221:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afonso CL, et al. African swine fever virus multigene family 360 and 530 genes affect host interferon response. J Virol. 2004;78:1858–1864. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1858-1864.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguero M, Blasco R, Wilkinson P, Vinuela E. Analysis of naturally occurring deletion variants of African swine fever virus: multigene family 110 is not essential for infectivity or virulence in pigs. Virology. 1990;176:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90244-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netherton C, Rouiller I, Wileman T. The subcellular distribution of multigene family 110 proteins of African swine fever virus is determined by differences in C-terminal KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention motifs. J Virol. 2004;78:3710–3721. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3710-3721.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction–the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W429–432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishihama Y, et al. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Molecular & cellular proteomics: MCP. 2005;4:1265–1272. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500061-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keil GM, Giesow K, Portugal R. A novel bromodeoxyuridine-resistant wild boar lung cell line facilitates generation of African swine fever virus recombinants. Arch Virol. 2014;159:2421–2428. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reed, L. J. & Muench, H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty Per Cent Endpoints. The American Lournal of Hygiene (1938).

- 37.Nagaraj N, et al. Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:548. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuhoff V, Arold N, Taube D, Ehrhardt W. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels including isoelectric focusing gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:255–262. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoscheck CM. Quantitation of protein. Methods in enzymology. 1990;182:50–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82008-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aken BL, et al. Ensembl 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D635–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The UniProt Consortium UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapman DA, Tcherepanov V, Upton C, Dixon LK. Comparison of the genome sequences of non-pathogenic and pathogenic African swine fever virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:397–408. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu W, Smith JW, Huang CM. Mass spectrometry-based label-free quantitative proteomics. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:840518. doi: 10.1155/2010/840518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grossmann J, et al. Implementation and evaluation of relative and absolute quantification in shotgun proteomics with label-free methods. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1740–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. www.R-project.org/ (2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.