Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether oral ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin and moxifloxacin increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmia in Korea’s general population.

Design

Population-based cohort study using administrative claims data on a national scale in Korea.

Setting

All primary, secondary and tertiary care settings from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015.

Participants

Patients who were prescribed the relevant study medications at outpatient visits.

Primary outcome measures

Each patient group that was prescribed ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin was compared with the group that was prescribed cefixime to assess the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia, fibrillation, flutter and cardiac arrest). Using logistic regression analysis with inverse probability of treatment weighting using the propensity score, OR and 95% CI for serious ventricular arrhythmia were calculated for days 1–7 and 8–14 after the patients commenced antibiotic use.

Results

During the study period, 4 888 890 patients were prescribed the study medications. They included 1 466 133 ciprofloxacin users, 1 141 961 levofloxacin users, 1 830 786 ofloxacin users, 47 080 moxifloxacin users and 402 930 cefixime users. Between 1 and 7 days after index date, there was no evidence of increased serious ventricular arrhythmia related to the prescription of ciprofloxacin (OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.06) and levofloxacin (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.29). Ofloxacin had a 59% reduced risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime during 1–7 days after prescription. Whereas the OR of serious ventricular arrhythmia after the prescription of moxifloxacin was 1.87 (95% CI 1.15 to 3.11) compared with cefixime during 1–7 days after prescription.

Conclusions

During 1–7 days after prescription, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were not associated with increased risk and ofloxacin showed reduced risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia. Moxifloxacin increased the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia.

Keywords: fluoroquinolone, ventricular arrhythmia, torsades de pointes, population-based study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a nationwide population-based study that included 4 888 890 patients who were prescribed oral fluoroquinolone or cefixime.

This is the largest study to date evaluating the association between oral fluoroquinolone use and serious ventricular arrhythmia.

This study adjusted the underlying characteristics and indications of the antibiotics for both the fluoroquinolone and cefixime groups using propensity score weighting.

This study reflected no baseline health information, such as laboratory or ECG data, because we used health claims data.

The number of deaths that occurred during the follow-up period could not be investigated.

Introduction

Fluoroquinolones are a broad-spectrum antibiotics prescribed for many infectious diseases. Common adverse effects of fluoroquinolones include gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhoea and nausea, and central nervous system side effects, such as headaches and dizziness.1 These side effects are mild, and fluoroquinolone use is mostly safe; however, rare but serious adverse effects have been reported, including tendon rupture, retinal detachment, aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection.2–8

Fluoroquinolones also have cardiac side effects. Several studies have reported QT interval increases after fluoroquinolone use,9–14 which can lead to ventricular arrhythmia. Cases of torsades de pointes occurrence associated with fluoroquinolone use have also been reported.15–19 Several population-based studies also reported that fluoroquinolones increased the risk of ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death.20–22 Despite these reports, the association of fluoroquinolones with arrhythmia remains contentious. A recent observational study in Denmark and Sweden reported that oral fluoroquinolone treatment was not associated with the risk of serious arrhythmia.23 This study compared 909 656 fluoroquinolone users with 9 09 656 penicillin V users, providing strong statistical power. However, the most frequently prescribed fluoroquinolone was ciprofloxacin; thus, the risk of arrhythmia by antibiotic type was undetermined. Previous studies have reported the risk of arrhythmia by fluoroquinolone type, but their results differed.

To clarify this issue, we used a large general population database in Korea to examine whether oral ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin increased the risk of ventricular arrhythmia compared with the risk associated with cefixime. We selected cefixime (an antibiotic with no proarrhythmic effect) as a comparison medication because fluoroquinolones and cefixime have overlapping indications.

Methods

Study design

This population-based cohort study included patients who had been prescribed oral fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin) or cefixime in the outpatient department from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015 (see online supplementary table 1). To reduce potential confounding by indication, oral cefixime was used as a control. Both fluoroquinolones and cefixime are frequently prescribed for respiratory diseases and urinary tract infections (UTIs) in Korea. Other studies used β-lactam antibiotics, such as amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate and penicillin V, as controls.21–23 However, in Korea, β-lactam antibiotics are not commonly used in UTI treatment; thus, cefixime was used in this study as a comparator. Cefixime is a medication with no proarrhythmic effects and is not in the list of drug-induced QT prolongation or torsades de pointes.24–29

bmjopen-2017-020974supp001.pdf (321.6KB, pdf)

Data source and ethics

We analysed claims data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) in South Korea. HIRA examines the medical expense claims data received from the National Health Insurance (NHI) and the appropriateness of medical care benefits.30 NHI covers almost 98% of the Korean population (approximately 50 million).31 HIRA claims data include comprehensive information on inpatient and outpatient medical services, such as treatment, medicines, procedures and diagnoses.30 In the HIRA database, all personally identifiable information was removed from the data sets, and anonymised codes representing each patient were included for to protect privacy protection.

Inclusion criteria and exposures

We included adult patients over 18 years old. Only the first prescribed study medication was included in the analysis if the patient was prescribed more than one antibiotic during the study period. Patients who were prescribed the relevant study medications outpatient visits in all primary, secondary and tertiary care settings were included.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients who were hospitalised within 30 days of the index date, which was defined as the date on which the study medication was prescribed. We also excluded patients who were prescribed antibiotics within 30 days prior to the index date, who were prescribed medication associated with QT interval prolongation or increased risk for developing torsades de pointes from 30 days before to 30 days after the index date (see online supplementary table 2), or who were already diagnosed with serious ventricular arrhythmia before the index date.

Outcome definition

The outcomes of serious ventricular arrhythmia included ventricular tachycardia, fibrillation, flutter and cardiac arrest. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (I472, I490.x, I460, I461 and I469) were used to identify the patients with serious ventricular arrhythmias. Only the main diagnostic codes were used. Because diagnostic codes are sometimes used in patients with existing arrhythmias, only the first diagnosis was used when patients had more than one diagnostic code for serious ventricular arrhythmia to focus on incidence outcomes. Because fluoroquinolone and cefixime are generally recommended to be prescribed for 7–14 days, we used observation periods of 1–7 days and 8–14 days after the index date to evaluate the adverse effects of these medications. These periods were chosen because acute side effects from the drug can develop during the administration period. Follow-up began on the index date and ended on the date of serious arrhythmia or 14 days after starting treatment, whichever came first.

Covariates

Covariates were defined by ICD-10 codes (see online supplementary table 3). The diseases included were hypertension, diabetes mellitus, acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, valve disorder, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, congenital heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, arterial disease, venous thromboembolism, dementia, rheumatic disease, peptic ulcer disease and chronic lung disease. Antibiotic indications were identified by primary diagnosis codes on the index date. Infection diagnoses included as covariates were upper respiratory, other respiratory, gastrointestinal, UTI, genitourinary tract and skin/wound infections, as well as pneumonia.

Statistical analyses

The number of serious ventricular arrhythmias was identified, and the incidence per 1 000 000 patients was calculated. Each patient group prescribed ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin was compared with the group prescribed cefixime to assess the risk of ventricular arrhythmia. Using logistic regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), we calculated the OR and 95% CIs of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime for days 1–7 and 8–14 after the index date.

We calculated the propensity scores of being prescribed ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin compared with cefixime using logistic regression. Age, sex, prescription month, all covariate-related comorbidities and antibiotic indications were included in the propensity models. IPTWs were calculated with propensity scores to adjust for baseline differences and control for confounding by indication.32 IPTW weights the inverse of the estimated propensity score for treated patients and the inverse of one minus the estimated propensity score for control patients.33 Propensity score matching has the disadvantage of including only a subset of subjects and controls in the analysis, but IPTW can be used without reducing sample number. We evaluated the baseline covariate balance between groups with standardised differences before and after IPTW. A standardised difference <0.1 indicated that covariates were well balanced between treatment and control patients.34

For the subgroup analyses, we divided patients by age, sex and cardiovascular disease history. Acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, valve disorder, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure and congenital heart disease were included as cardiovascular diseases. We defined cardiovascular disease using the same ICD-10 code as that used to define baseline comorbidities. The propensity score for each subgroup and drug type was calculated and the ORs were calculated, respectively. No data were missing in this study. Statistical analyses were performed using R, V.3.1.1 (www.R-project.org).

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Study population characteristics

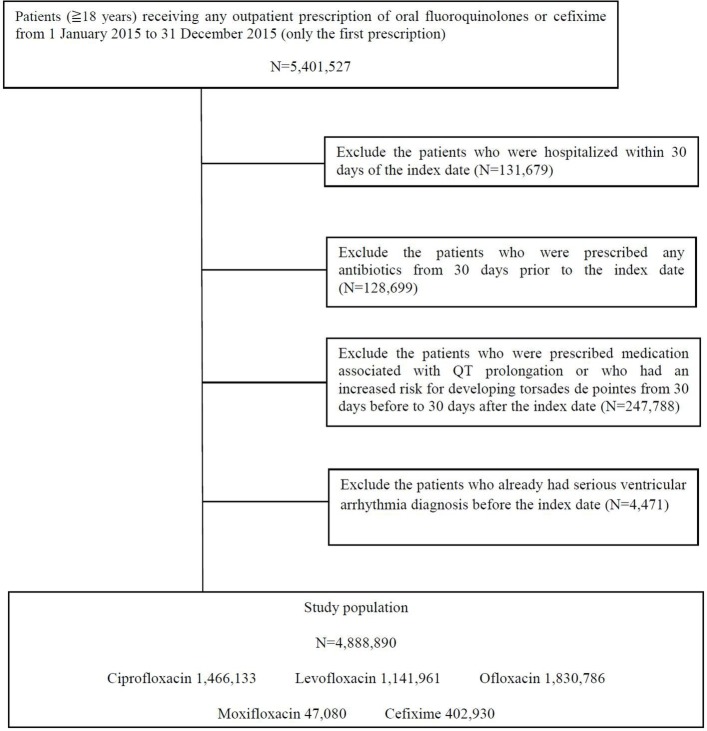

We extracted 5 401 527 outpatients who were prescribed oral fluoroquinolones and cefixime from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015. After excluding 512 637 patients who were (1) hospitalised within 30 days of the index date (n=131 679), (2) prescribed antibiotics from 30 days prior to the index date (n=128 699), (3) prescribed medication associated with QT interval prolongation or increased risk for developing torsades de pointes from 30 days before to 30 days after the index date (n=247 788) or (4) diagnosed with serious ventricular arrhythmia before the index date (n=4471), 4 888 890 patients were included in the analysis (figure 1). The study population consisted of 1 466 133 ciprofloxacin users, 1 141 961 levofloxacin users, 1 830 786 ofloxacin users, 47 080 moxifloxacin users and 402 930 cefixime users.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

The baseline characteristics of the study population before weighting are presented in table 1. Compared with cefixime users, moxifloxacin users were older and had more comorbidities. Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and ofloxacin users had similar baseline comorbidities as cefixime users, except that chronic lung disease was less prevalent among ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin users and cancer was less prevalent among ofloxacin users. After the study population had been weighting using the IPTW, all baseline differences were less than 0.1 standardised differences (see online supplementary tables 4–7).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients using study medications

| Cefixime | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Ofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| No of subjects | 402 930 | 1 466 133 | 1 141 961 | 1 830 786 | 47 080 |

| Age, mean±SD | 49.3±17.7 | 48.5±17.3 | 50.4±16.7 | 50.3±16.9 | 58.4±17.4 |

| No of females (%) | 238 329 (59.1) | 951 813 (64.9) | 643 076 (56.3) | 1 120 119 (61.2) | 23 586 (50.1) |

| No of comorbidities (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 121 529 (30.2) | 410 360 (28.0) | 346 918 (30.4) | 540 934 (29.5) | 21 690 (46.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 97 779 (24.3) | 321 483 (21.9) | 268 447 (23.5) | 382 877 (20.9) | 17 977 (38.2) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 6536 (1.6) | 17 451 (1.2) | 15 209 (1.3) | 11 731 (1.0) | 1292 (2.7) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 45 810 (11.4) | 137 303 (9.4) | 122 740 (10.7) | 161 602 (8.8) | 9408 (20) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1450 (0.4) | 3668 (0.3) | 3443 (0.3) | 3924 (0.2) | 438 (0.9) |

| Valve disorder | 1826 (0.5) | 4971 (0.3) | 4643 (0.4) | 6219 (0.3) | 513 (1.1) |

| Arrhythmia | 14 387 (3.6) | 45 727 (3.1) | 38 751 (3.4) | 53 536 (2.9) | 2761 (5.9) |

| Congestive heart failure | 21 753 (5.4) | 59 507 (4.1) | 55 276 (4.8) | 68 471 (3.7) | 5724 (12.2) |

| Congenital heart disease | 550 (0.1) | 1599 (0.1) | 1430 (0.1) | 1894 (0.1) | 110 (0.2) |

| Cancer | 43 336 (10.8) | 128 612 (8.8) | 118 618 (10.4) | 122 116 (6.7) | 10 285 (21.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 42 741 (10.6) | 127 394 (8.7) | 113 241 (9.9) | 155 453 (8.5) | 8389 (17.8) |

| Renal disease | 27 440 (6.8) | 93 946 (6.4) | 73 935 (6.5) | 83 202 (4.5) | 5657 (12) |

| Arterial disease | 58 202 (14.4) | 201 275 (13.7) | 173 004 (15.1) | 268 362 (14.7) | 9298 (19.7) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 5613 (1.4) | 15 375 (1.0) | 14 016 (1.2) | 16 571 (0.9) | 1704 (3.6) |

| Dementia | 17 245 (4.3) | 48 445 (3.3) | 41 097 (3.6) | 46 626 (2.5) | 4046 (8.6) |

| Rheumatic disease | 29 610 (7.3) | 97 980 (6.7) | 77 971 (6.8) | 112 629 (6.2) | 4453 (9.5) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 148 247 (36.8) | 527 527 (36.0) | 418 871 (36.7) | 636 452 (34.8) | 21 304 (45.3) |

| Chronic lung disease | 215 194 (53.4) | 633 215 (43.2) | 586 894 (51.4) | 810 357 (44.3) | 36 096 (76.7) |

| No of antibiotic indications (%) | |||||

| Upper respiration infection | 41 000 (10.2) | 34 919 (2.4) | 71 542 (6.3) | 200 376 (10.9) | 2024 (4.3) |

| Pneumonia | 17 362 (4.3) | 13 792 (0.9) | 54 016 (4.7) | 10 048 (0.5) | 10 567 (22.4) |

| Other respiratory infection | 31 943 (7.9) | 49 097 (3.3) | 118 629 (10.4) | 266 793 (14.6) | 2898 (6.2) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 10 997 (2.7) | 258 359 (17.6) | 26 806 (2.3) | 116 001 (6.3) | 142 (0.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 497 (6.1) | 477 439 (32.6) | 255 878 (22.4) | 204 458 (11.2) | 396 (0.8) |

| Genitourinary infection | 10 357 (2.6) | 103 874 (7.1) | 104 759 (9.2) | 75 822 (4.1) | 806 (1.7) |

| Skin/wound infection | 15 212 (3.8) | 13 240 (0.9) | 20 509 (1.8) | 47 573 (2.6) | 589 (1.3) |

Development of serious ventricular arrhythmia

Serious ventricular arrhythmia incidence, weighted ORs and 95% CIs for days 1–7 after antibiotic initiation are presented in table 2. ORs for serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime were 0.72 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.06), 0.92 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.29), 0.41 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.61) and 1.87 (95% CI 1.15 to 3.11) for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin and moxifloxacin, respectively. Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were not associated with an increased risk, while moxifloxacin was associated with a 1.87-fold increased risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia. Ofloxacin was associated with a 59% reduced risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime for 1–7 days after the index date.

Table 2.

Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia associated with oral fluoroquinolones compared with cefixime 1–7 days after the index date

| Cefixime | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Ofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| No of serious ventricular arrhythmia | 18 | 31 | 48 | 26 | 7 |

| Incidence per 1 000 000 subjects | 44.7 | 21.1 | 42.0 | 14.2 | 148.7 |

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.66 to 1.29) | 0.41 (0.27 to 0.61) | 1.87 (1.15 to 3.11) |

IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

The serious ventricular arrhythmia incidence and weighted OR for the 8–14 days postprescription are presented in table 3. ORs for serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime were 0.44 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.65), 1.08 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.69), 0.58 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.92) and 1.78 (95% CI 0.86 to 3.88) for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin and moxifloxacin, respectively. Risk reductions of 66% and 42% were found for ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin, respectively. No evidence of an increased risk was found for levofloxacin. Moxifloxacin was associated with a 1.78-fold increased risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia for 8–14 days after the index date; however, this increased risk was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia associated with oral fluoroquinolones compared with cefixime for 8–14 days after the index date

| Cefixime | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Ofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| No of serious ventricular arrhythmia | 8 | 24 | 29 | 21 | 4 |

| Incidence per 1 000 000 subjects | 19.9 | 16.4 | 25.4 | 11.5 | 85.0 |

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.44 (0.29 to 0.65) | 1.08 (0.70 to 1.69) | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.92) | 1.78 (0.86 to 3.88) |

IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Subgroup analyses

Table 4 shows the weighted ORs for serious ventricular arrhythmia 1–7 days after prescribing ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin or moxifloxacin compared with cefixime according to history of cardiovascular disease, age and gender. The risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and ofloxacin users was not increased compared with that for cefixime users. Moxifloxacin users with histories of cardiovascular disease (OR 2.36; 95% CI 1.17 to 5.12) and those over 65 years old (OR 2.04: 95% CI 1.16 to 3.73) had significantly increased risks of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime users.

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of the risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia associated with oral fluoroquinolones assessed in this study compared with cefixime for 1–7 days after the index date

| Cefixime | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Ofloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| History of cardiovascular disease | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.61 (0.34 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.58 to 1.57) | 0.47 (0.24 to 0.85) | 2.36 (1.17 to 5.12) |

| Without cardiovascular disease | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.79 (0.47 to 1.33) | 0.86 (0.54 to 1.34) | 0.36 (0.21 to 0.60) | 1.63 (0.84 to 3.29) |

| Age ≥65 | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.78 (0.48 to 1.24) | 1.06 (0.71 to 1.60) | 0.36 (0.22 to 0.57) | 2.04 (1.16 to 3.73) |

| Age<65 | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.64 (0.32 to 1.25) | 0.96 (0.51 to 1.81) | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.85) | 1.59 (0.60 to 4.58) |

| Male | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.61 (0.36 to 0.99) | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.25) | 0.53 (0.29 to 0.96) | 1.91 (1.00 to 3.80) |

| Female | |||||

| OR (95% CI) (IPTW) | Reference | 0.62 (0.35 to 1.07) | 0.89 (0.54 to 1.46) | 0.33 (0.19 to 0.56) | 1.79 (0.87 to 3.92) |

IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Discussion

Overall findings

The general population data revealed that ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were not associated with an increased risk for serious ventricular arrhythmia for 1–7 days after the prescription date and that ofloxacin was associated with a reduced risk of arrhythmia. Moxifloxacin use was associated with a 1.87-fold increased risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime during the first week after initiating the drug. The risk of ventricular arrhythmia was especially high in moxifloxacin users who were older or had cardiovascular disease. For 8–14 days after the index date, moxifloxacin showed a 1.78-fold increased risk; however, the 95% CI was not statistically significant. All moxifloxacin subgroups showed a high risk, but this risk was statistically significant only in patients with cardiovascular disease and those over 65 years old. The 95% CIs were wide because the number of moxifloxacin users (n=47 080) included in the study was fewer than that for other drugs, and the number of serious ventricular arrhythmias was only 7 for days 1–7 after the index date and 4 for days 8–14. Further studies with more subjects are needed to confirm the risk of moxifloxacin.

Drug-induced QT interval prolongation

Medications can prolong QT intervals, which can lead to fatal ventricular arrhythmias, such as torsades de pointes.27 28 Torsades de pointes is a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, which can lead to ventricular fibrillation or sudden cardiac death. Drug-induced QT interval prolongation occurs by inhibiting of cardiac voltage-gated potassium channels encoded by the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG).35 Blocking the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) through hERG channels delays cardiac repolarisation, represented by prolonged QT intervals.

Among the medications considered to be associated with prolonged QT intervals, fluoroquinolones and macrolides are the most commonly prescribed drugs in clinical practice24; however, QT interval prolongation by fluoroquinolones appears to differ depending by type. A prospective trial suggested that recommended ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin doses have little effect on QT intervals, while moxifloxacin induces the greatest QT interval prolongation.10 After 7 days of moxifloxacin use, the corrected QT interval was prolonged by 6 ms relative to baseline. Regarding supratherapeutic fluoroquinolone doses, all three fluoroquinolones increased QT intervals compared with placebo, with moxifloxacin most strongly affecting the interval.11 The increased QT interval means for the 24 hours period after treatment were 2.3–4.9 ms, 3.5–4.9 ms and 16.3–17.8 ms for 1500 mg ciprofloxacin, 1000 mg levofloxacin and 800 mg moxifloxacin, respectively.11 No studies have been published on the effect of ofloxacin on QT intervals. However, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were significantly less potent hERG channel inhibitors than sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin or moxifloxacin.36 Ofloxacin was the least potent hERG channel inhibitor. In contrast, sparfloxacin and grepafloxacin, the most potent hERG channel inhibitors, were withdrawn from the market due to QT interval prolongation.

Comparison with other population-based studies

In a study on veterans in the USA,21 levofloxacin use was associated with a 3.13-fold increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias and a 2.49-fold increased risk of all-cause death compared with amoxicillin. The veteran population was older (mean age, 56.8 years) than our cohort (mean age, cefixime, 49.3 years; levofloxacin, 50.4 years), which likely explains the different results. In another study in USA, 0.3, 5.4 and 2.1 cases of torsades de pointes per 10 million prescriptions from 1996 to 2001 for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and ofloxacin, respectively.37 A recent cohort study in Denmark and Sweden23 found no association between fluoroquinolone use and serious arrhythmias in the general population; however, because 82% of the prescribed fluoroquinolones were ciprofloxacin, it remains possible that other fluoroquinolones could increase the risk. In a US study in a Tennessee Medicaid cohort,38 patients who took ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin showed no increased risk for cardiovascular death compared with patients who took amoxicillin for a 10-day treatment course. A cohort study from Taiwan22 on the risks of cardiac arrhythmia among patients using moxifloxacin, levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin reported that moxifloxacin use was associated with a 3.30-fold increased risk for ventricular arrhythmia compared with amoxicillin–clavulanate, with no risk associated with levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin use.

In this study, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were not associated with increased ventricular arrhythmia risk, however, some case reports exist on QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes after fluoroquinolone use.15–19 Most of these cases were patients with concomitant use of other medications associated with QT interval prolongation or with multiple risk factors associated with drug-induced arrhythmia. The risk factors for drug-induced arrhythmia are baseline QT interval prolongation, rapid intravenous drug infusion, digitalis therapy, bradycardia, organic heart disease and electrolyte imbalances.35 Our study excluded patients who were prescribed drugs associated with QT interval prolongation, and we could not confirm whether the risk of ventricular arrhythmia was increased by the concomitant fluoroquinolone use with drugs that increase the risk of torsades de pointes. We also could not assess whether intravenous use was associated with increased risk because this study was conducted only in oral fluoroquinolone users. Furthermore, no baseline ECG or electrolyte data were available. Further studies are needed to determine whether fluoroquinolones increase the risk of arrhythmias in patients with these risk factors.

In this study, ofloxacin users had a reduced risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia. However, it is not possible to conclude that ofloxacin has an antiarrhythmic effect. In fact, cases of torsades de pointes had been reported to occur after taking ofloxacin.37 39 A study with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System data reported a reduced risk of torsades de pointes, but the adjusted OR was not statistically significant (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.03 to 4.38).39 In addition, reason for the reduced risk of arrhythmia in ofloxacin users cannot be clearly explained. Additional clinical and population-based studies are needed.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that it is the largest study to date evaluating the association between oral fluoroquinolone use and serious ventricular arrhythmia. This study was a nationwide population-based study including 4 888 890 patients who were prescribed oral fluoroquinolone or cefixime. In addition, the datasets had no missing values, thus minimising the number of subjects. Second, propensity score weighting was performed to adjust the underlying characteristics and antibiotic indications of both the fluoroquinolone and cefixime groups. In the propensity score matching, unmatched subjects occur and subject numbers decreased. In this study, all subjects can be included for comparison using IPTW.

This study also had several limitations. First, we cannot rule out the effect of selection bias. We attempted to adjust the underlying antibiotic characteristics and indications of the fluoroquinolone and cefixime groups using IPTW to correct for this selection bias. However, it is possible that the ICD-10 codes used to define covariates in the propensity score weighting were inappropriate. For example, the range of chronic lung diseases that we defined was wide, with 40%–70% of the individuals in each antibiotic group having chronic lung disease. This wide range of diagnostic codes suggests that chronic respiratory illnesses that are unrelated to the antibiotic prescription may have been included. The propensity score obtained using these covariates may insufficiently reflect the actual antibiotic prescription. Second, there may be a residual confounding effect. This study did not reflect baseline health information, such as laboratory or ECG data, because we used health claims data. However, we tried to reduce residual confounding by excluding patients who were recently admitted, prescribed antibiotics or prescribed medications that prolonged QT intervals. Third, the ICD-10 code defining the serious ventricular arrhythmia outcome was not directly validated in the Korean population. In one study, however, ICD-9 code 427.x predicted a ventricular arrhythmia with a positive predictive value of 78%–100%.40 ICD-9 code 427.x corresponds to the ICD-10 code used in our study. Fourth, because death data were not linked to the HIRA data, the number of deaths that occurred during the follow-up period was unconfirmed. Finally, the drug dose was not investigated, and the effect of the drug dose was not analysed in this study. Further studies are needed to determine how the effects of fluoroquinolone on arrhythmias vary with drug dose.

Conclusion

In this population-based study, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin were not associated with serious ventricular arrhythmia, and ofloxacin reduced the risk of arrhythmia. Moxifloxacin was associated with a 1.87-fold increased risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia compared with cefixime for 1–7 days after being prescribed. Additional studies in other populations are required to ensure that these findings are valid for patients with risk factors excluded in this cohort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Contributors: YC contributed to the design of the study, cleaned and analysed the data, interpreted the data, and drafted and revised the paper. HSP contributed to the design of the study, interpreted the data and critically revised the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jeju National University Hospital with informed consent waived (IRB No. JEJUNUH 2017-01-013).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: HIRA data are third-party data not owned by the authors. Raw data can be accessed with permission from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) in Korea.

References

- 1. Owens RC, Ambrose PG. Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(Suppl 2):S144–S157. 10.1086/428055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh S, Nautiyal A. Aortic dissection and aortic aneurysms associated with fluoroquinolones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2017;130:1449–57. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. . Association between oral fluoroquinolone use and retinal detachment. JAMA 2013;310:2184–90. 10.1001/jama.2013.280500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raguideau F, Lemaitre M, Dray-Spira R, et al. . Association between oral fluoroquinolone use and retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:415–21. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.6205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuo SC, Chen YT, Lee YT, et al. . Association between recent use of fluoroquinolones and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:197–203. 10.1093/cid/cit708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daneman N, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Fluoroquinolones and collagen associated severe adverse events: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010077 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wise BL, Peloquin C, Choi H, et al. . Impact of age, sex, obesity, and steroid use on quinolone-associated tendon disorders. Am J Med 2012;125:1228.e23–e28. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee CC, Lee MT, Chen YS, et al. . Risk of aortic dissection and aortic aneurysm in patients taking oral fluoroquinolone. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1839–47. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Démolis JL, Kubitza D, Tennezé L, et al. . Effect of a single oral dose of moxifloxacin (400 mg and 800 mg) on ventricular repolarization in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000;68:658–66. 10.1067/mcp.2000.111482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsikouris JP, Peeters MJ, Cox CD, et al. . Effects of three fluoroquinolones on QT analysis after standard treatment courses. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2006;11:52–6. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2006.00082.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Noel GJ, Natarajan J, Chien S, et al. . Effects of three fluoroquinolones on QT interval in healthy adults after single doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003;73:292–303. 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00009-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noel GJ, Goodman DB, Chien S, et al. . Measuring the effects of supratherapeutic doses of levofloxacin on healthy volunteers using four methods of QT correction and periodic and continuous ECG recordings. J Clin Pharmacol 2004;44:464–73. 10.1177/0091270004264643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haq S, Khaja M, Holt JJ, et al. . The Effects of Intravenous Levofloxacin on the QT Interval and QT Dispersion. Int J Angiol 2006;15:16–19. 10.1007/s00547-006-2048-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bloomfield DM, Kost JT, Ghosh K, et al. . The effect of moxifloxacin on QTc and implications for the design of thorough QT studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;84:475–80. 10.1038/clpt.2008.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daya SK, Gowda RM, Khan IA. Ciprofloxacin- and hypocalcemia-induced torsade de pointes triggered by hemodialysis. Am J Ther 2004;11:77–9. 10.1097/00045391-200401000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ibrahim M, Omar B. Ciprofloxacin-induced torsade de pointes. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:252.e5–9. 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nair MK, Patel K, Starer PJ. Ciprofloxacin-induced torsades de pointes in a methadone-dependent patient. Addiction 2008;103:2062–4. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gandhi PJ, Menezes PA, Vu HT, et al. . Fluconazole- and levofloxacin-induced torsades de pointes in an intensive care unit patient. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003;60:2479–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dale KM, Lertsburapa K, Kluger J, et al. . Moxifloxacin and torsade de pointes. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41:336–40. 10.1345/aph.1H474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zambon A, Polo Friz H, Contiero P, et al. . Effect of macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibacterials on the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac arrest: an observational study in Italy using case-control, case-crossover and case-time-control designs. Drug Saf 2009;32:159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rao GA, Mann JR, Shoaibi A, et al. . Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:121–7. 10.1370/afm.1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chou HW, Wang JL, Chang CH, et al. . Risks of cardiac arrhythmia and mortality among patients using new-generation macrolides, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors: a Taiwanese nationwide study. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:566–77. 10.1093/cid/ciu914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Inghammar M, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. . Oral fluoroquinolone use and serious arrhythmia: bi-national cohort study. BMJ 2016;352:i843 10.1136/bmj.i843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abo-Salem E, Fowler JC, Attari M, et al. . Antibiotic-induced cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Ther 2014;32:19–25. 10.1111/1755-5922.12054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Owens RC, Nolin TD. Antimicrobial-associated QT interval prolongation: pointes of interest. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1603–11. 10.1086/508873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li EC, Esterly JS, Pohl S, et al. . Drug-induced QT-interval prolongation: considerations for clinicians. Pharmacotherapy 2010;30:684–701. 10.1592/phco.30.7.684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yap YG, Camm AJ. Drug induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Heart 2003;89:1363–72. 10.1136/heart.89.11.1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cubeddu LX. Iatrogenic QT abnormalities and fatal arrhythmias: mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr Cardiol Rev 2009;5:166–76. 10.2174/157340309788970397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Isbister GK. Risk assessment of drug-induced QT prolongation. Aust Prescr 2015;38:20–4. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2015.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim JA, Yoon S, Kim LY, et al. . Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:718–28. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Song SO, Jung CH, Song YD, et al. . Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J 2014;38:395–403. 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Inverse probability weighting. BMJ 2016;352:i189 10.1136/bmj.i189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brookhart MA, Wyss R, Layton JB, et al. . Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:604–11. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28:3083–107. 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1013–22. 10.1056/NEJMra032426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kang J, Wang L, Chen XL, et al. . Interactions of a series of fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs with the human cardiac K+ channel HERG. Mol Pharmacol 2001;59:122–6. 10.1124/mol.59.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Frothingham R. Rates of torsades de pointes associated with ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21:1468–72. 10.1592/phco.21.20.1468.34482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. . Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1881–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poluzzi E, Raschi E, Motola D, et al. . Antimicrobials and the risk of torsades de pointes: the contribution from data mining of the US FDA adverse event reporting system. Drug Saf 2010;33:303–14. 10.2165/11531850-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tamariz L, Harkins T, Nair V. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying ventricular arrhythmias using administrative and claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(Suppl 1):148–53. 10.1002/pds.2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020974supp001.pdf (321.6KB, pdf)