Abstract

The cardiac extracellular matrix is a complex architectural network that serves many functions, including providing structural and biochemical support to surrounding cells and regulating intercellular signaling pathways. Cardiac function is directly affected by extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, and alterations of the ECM contribute to the progression of heart failure. Initially, collagen deposition is an adaptive response that aims to preserve tissue integrity and maintain normal ventricular function. However, the synergistic effects of proinflammatory and profibrotic responses induce a vicious cycle, which causes excess activation of myofibroblasts, significantly increasing collagen deposition and accumulation in the matrix. Furthermore, excess synthesis and activation of the enzyme lysyl oxidase (LOX) during disease increases collagen cross-linking, which significantly increases collagen resistance to degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). In the present study, the aortocaval fistula model of volume overload (VO) was used to determine whether LOX inhibition could prevent adverse changes in the ECM and subsequent cardiac dysfunction. The major findings from this study were that LOX inhibition 1) prevented VO-induced increases in left ventricular wall stress; 2) partially attenuated VO-induced ventricular hypertrophy; 3) completely blocked the increases in fibrotic proteins, including collagens, MMPs, and their tissue inhibitors; and 4) prevented the VO-induced decline in cardiac function. It remains unclear whether a direct interaction between LOX and MMPs exists; however, our experiments suggest a potential link between the two because LOX inhibition completely attenuated VO-induced increases in MMPs. Overall, our study demonstrated key cardioprotective effects of LOX inhibition against adverse cardiac remodeling due to chronic VO.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Although the primary role of lysyl oxidase (LOX) is to cross-link collagens, we found that elevated LOX during cardiac disease plays a key role in the progression of heart failure. Here, we show that inhibition of LOX in volume-overloaded rats prevented the development of cardiac dysfunction and improved ventricular collagen and matrix metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase profiles.

Keywords: cross link, extracellular matrix, fibrosis, heart failure, ventricular

INTRODUCTION

The cardiac extracellular matrix (ECM) creates a complex architectural network and has a multitude of functions that include preserving cardiomyocyte alignment and providing tensile strength to the myocardium (19, 41, 65). Abnormalities in the architectural scaffolding of the ECM can be noted during various pathological mechanisms of myocardial injury leading to heart failure (7, 23). Cardiac myocytes are central to the contractile function of the myocardium; however, the interstitium and its fibrillar collagen matrix play a critical role in determining cardiac performance (46). There are five different known types of fibrillar collagens, with type I and type III representing ~85% and 15%, respectively (65). This extensive collagenous network is produced by cardiac fibroblasts to maintain the structural integrity of the myocardium (10). Disruption of these collagens is thought to play a key role in myocyte misalignment observed in heart failure (23, 26).

The relative abundance of collagen types I and III and their extent of cross-linking dictate the passive mechanical properties of the heart (12). In dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), these collagens are overproduced and accumulate in the interstitial and perivascular regions of the myocardium (28). Lysyl oxidase (LOX) is a copper-dependent amine oxidase that is crucial in the covalent cross-linking of collagens (53). The degree of cross-linking determines the solubility, stiffness, and resistance to degradation of the resulting fibrils (9). During myocardial stress and heart failure, LOX expression and activity are significantly elevated (36, 54).

Homeostasis of the myocardial ECM and its dynamic regulation involve an ongoing cycle of synthesis and degradation. In a healthy myocardium, ECM turnover is relatively low, but during pathological conditions turnover can increase dramatically (~5- to 10-fold during myocardial infarction) (31). Increased collagen turnover and ECM fibrosis are a hallmark of cardiac remodeling in DCM, which includes an upregulation of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and their inhibitors, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (47). Upregulation of MMP activity can be observed in animal models of end-stage heart failure (50, 57). Alterations in the balance of matrix synthesis and degradation via changes in MMP activity are thought to be crucial in the progression of pathological remodeling (25, 65), and pharmacological inhibition of MMP activity has been shown to attenuate the progression of ventricular remodeling associated with cardiovascular disease (29, 34, 57).

Using the aortocaval fistula (ACF) model of biventricular volume overload (VO) to induce DCM, we identified markedly increased LOX expression and activity in failing hearts relative to compensated and unstressed hearts (15). We also demonstrated a remarkable cardioprotective effect of LOX inhibition on both systolic and diastolic function (16). Here, we expand our efforts to identify the mechanisms involved in the cardioprotective effects of LOX inhibition against VO-induced adverse ventricular remodeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were performed using 8- to 9-wk-old male Sprague-Dawley (Harlan Hsd:SD) rats weighing ~250 g at surgery. Rats were housed under standard environmental conditions and maintained on commercial rat chow (Harlan Teklad 2018) and tap water ad libitum. All experiments conformed with the principles of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed.) and were approved by our institution’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical rat model of chronic VO.

Anesthesia was induced with isoflurane (4% induction/3% maintenance, balance oxygen). A ventral abdominal laparotomy was performed to expose the aorta and caudal vena cava. The abdominal ACF was surgically created to induce VO, as previously described (16). Briefly, the aorta and vena cava were occluded, and a short-bevel 18-gauge needle was inserted into the exposed ventral abdominal aorta and advanced through the medial wall of the vena cava, creating a shunt below the renal arteries. The needle was withdrawn, and the aortic puncture sealed with cyanoacrylate. Creation of a successful shunt was verified visually by mixture of arterial and venous blood within the vena cava. The surgical procedure was performed by one surgeon to minimize variability. Successful ACF creation was also confirmed at 2 wk postsurgery by echocardiography [increased left ventricular (LV) internal diameter]. Sham surgeries were similarly performed but without the creation of a fistula. Postoperative analgesia was provided by buprenorphine hydrochloride.

Experimental timeline.

The effects of LOX inhibition on remodeling induced by VO were studied in the following four age-matched groups: sham-operated controls (sham group), sham-operated controls with LOX inhibition (sham + B group), fistula-induced VO (VO group), and VO with LOX inhibition (VO + B group). Rats were randomly assigned to receive either vehicle (saline) or LOX inhibitor. Two weeks after sham or ACF surgery, the LOX inhibitor, β-aminopropionitrile (BAPN; A-3134, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was administered at 100 mg·kg−1·day−1 via an osmotic pump (Alzet, Cupertino, CA) placed in the abdominal cavity. We chose to administer the LOX inhibitor at 2 wk postsurgery to limit the potential impact on wound healing and to initiate inhibition before the VO-associated adverse remodeling and dysfunction were apparent.

Pressure-volume analysis.

At the experimental end point of 14 wk, LV pressure-volume loop analysis was used to assess cardiac function. Rats were weighed, anesthetized with isoflurane (3%), intubated, and attached to a ventilator. The chest was opened to expose the apex of the heart. A small needle was used to puncture the heart at the apex, and a Scisense pressure-volume catheter (FTS-1912B-9018 9-mm fixed segment for sham surgery and FTE-1918B-E218 multisegment for VO) was the inserted into the LV. After 5 min of stabilization, LV pressure and volume data were collected. Blood-filled cuvettes of known volume were used for calibration. Cardiac output (CO) was measured using a Doppler flow probe (model 3-SB, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) on the aortic arch. Data analyses were performed using Labscribe software with built-in pressure-volume loop analysis functions. All measures of cardiac function were evaluated from a minimum of 10 consecutive pressure-volume loops. After functional assessment, the heart was removed, placed in ice-cold PBS, and the LVs and right ventricles (RVs) were separated and weighed. A portion of the mid-LV region was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the remainder was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for further assay. Lung wet weight was also recorded.

Analysis of the collagen matrix.

The interstitial collagen volume fraction (CVF) was measured in mid-LV sections at the experimental end point of 14 wk. LV sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were cut, attached to slides, and stained with collagen-specific picrosirius red. The CVF of the section was determined by analyzing a minimum of 15 interstitial regions from 2 sections of each heart. Perivascular collagen was excluded from the measurements. Images were captured (×20) and processed using a Nikon Eclipse model TE2000-U fluorescence microscope and NIS Elements software. CVF was expressed as a percentage of the total area for each LV section and then group averaged.

LOX-dependent collagen cross-linking.

Pyridinoline (PYD) was quantified in mid-LV heart tissue using a commercial assay (PYD kit 8019, Quidel, San Diego, CA). Diluted (1:40) acid hydrolysates of LV tissue were used.

Western blot analysis.

Samples of the LV free wall were homogenized with RIPA buffer and HALT Protease Inhibitor Cocktail with EDTA (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Western blots were performed as previously described (17). Enhanced chemiluminescence was used to visualize immunostaining. Antibodies used for this study include collagen type I (ab34710, Abcam), collagen type III (ab7778, Abcam), MMP-2 (ab37150, Abcam), MMP-8 (ab81286, Abcam), MMP-9 (ab38898, Abcam), MMP-13 (ab39012, Abcam), MMP-14 (ab53712, Abcam), TIMP-1 (ab770, Abcam), TIMP-2 (ab180630, Abcam), TIMP-3 (ab85926, Abcam), TIMP-4 (ab58425, Abcam), and GAPDH (Abcam, Ab9485). Data were collected and analyzed using a Carestream Gel Logic 2200 Pro imaging system.

Data and statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad software (Prism, San Diego, CA). Grouped data comparisons were made by one- or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. Intergroup comparisons were made using a Dunnett’s posttest.

RESULTS

LOX inhibition attenuated VO-induced cardiac wall stress.

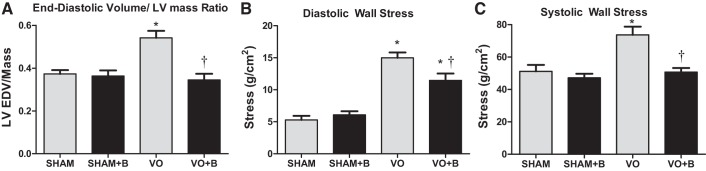

Two estimates of LV wall stress were made. The first calculation used Laplace’s law to establish a ratio between end-diastolic volume (EDV) and LV mass, such that EDV/LV mass was directly proportional to cardiac wall stress. A disproportional increase in EDV or decrease in LV mass leads to increased LV wall stress. VO caused a significant increase in the EDV-to-LV mass ratio, indicative of increased diastolic stress (47% increase vs. the sham group; Fig. 1A). LOX inhibition completely prevented this increase, suggesting a normalization of diastolic wall stress (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition prevented volume overload (VO)-induced increases in wall stress. Animals were divided into the following four groups: sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group). VO caused an increase in the end-diastolic volume (EDV)-to-LV mass ratio, indicative of increased stress, and LOX inhibition completely prevented this increase (A). The equation in the LOX inhibition attenuated VO-induced cardiac wall stress section was used to calculate diastolic wall stress (B) and systolic wall stress (C). VO led to an increase in both diastolic and systolic wall stresses, which were both attenuated by the LOX inhibitor. n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

The second means of estimating cardiac wall stress used the following equation (21, 42, 64):

| (1) |

where P is LV end-diastolic pressure (EDP) or end-systolic pressure (ESP; in mmHg), V is LV EDV (in ml) or end-systolic volume (ESV; in ml), and M is LV mass (in g). Using the above equation, developed LV wall stress was derived as the difference between peak isovolumetric and end-diastolic stress as previously described by Weber et al. (64). Rats with VO had a significant increase in both diastolic and systolic wall stress (184% and 44% increases, respectively, vs. sham rats; Fig. 1, B and C). There was only a partial prevention of increased diastolic wall stress (Fig. 1B) by LOX inhibition, but the increases in systolic stress were completely prevented (Fig. 1C). These data indicate a strong protective effect of LOX inhibition against VO-induced wall stress.

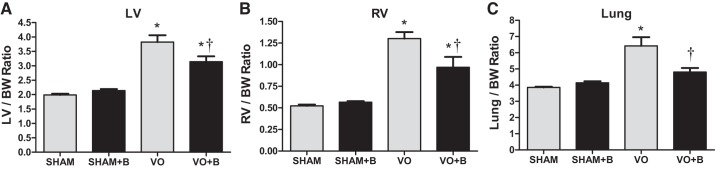

VO-induced ventricular hypertrophy.

All weight measurements were normalized to body weight. There were no changes in body weight between any of the groups throughout the experimental time course. LV and RV weights were used as markers of hypertrophy. Consistent with our previous studies, VO caused significant LV and RV hypertrophy (92% and 149% increases, respectively, vs. the sham group; Fig. 2). LOX inhibition partially attenuated the VO-induced hypertrophy of the LV and RV (18% and 25% decreases, respectively, vs. the VO group; Fig. 2). VO also caused a significant increase in lung weights (66% increase vs. the sham group; Fig. 2), which was significantly attenuated in the VO + B group (25% decrease vs. the VO group; Fig. 2). The finding of reduced hypertrophy and lung weights in the treated group suggests a slowing of the progression of adverse remodeling caused by chronic VO.

Fig. 2.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition partially prevented volume overload (VO)-induced increases in left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) mass as well as lung wet weight. All measures were normalized to body weight (BW). There were no significant differences in BW between groups [sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group)]. VO for 14 wk caused significant LV and RV hypertrophy. Lung wet weights were also increased by VO, indicating pulmonary edema. LOX inhibition attenuated the increases in LV and RV mass and completely prevented increases in lung wet weight. n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

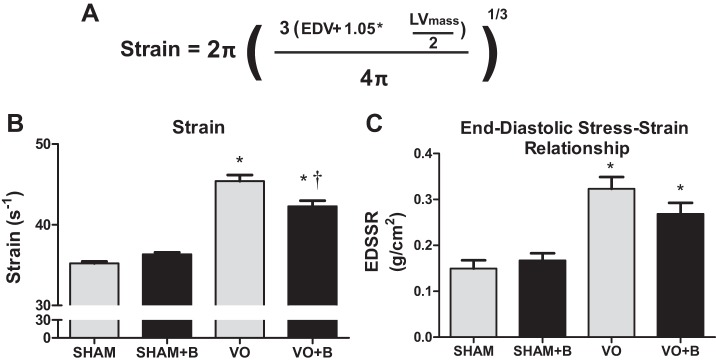

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced increases in LV strain and stiffness.

Because VO is marked by significant increases in chamber size, it was critical to consider differences in chamber size when assessing LV compliance. Therefore, strain was calculated using the equation shown in Fig. 3A. VO was associated with a significant increase in LV strain (29% increase vs. the sham group; Fig. 3B), which was only partially prevented by LOX inhibition. Next, we calculated the end-diastolic stress-to-strain ratio, which is indicative of LV stiffness. The VO group had the highest end-diastolic stress-to-strain ratio, indicative of increased chamber stiffness (116% increase vs. the group; Fig. 3C). Although there was a trend toward reduced stiffness in the VO + B group relative to the untreated VO group, diastolic stress/strain remained elevated above the sham control group. These findings of attenuated LV strain in the treated VO group were consistent with our measures of wall stress.

Fig. 3.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition completely prevented volume overload (VO)-induced increases in left ventricular (LV) strain but not LV stiffness. A: equation used to calculate LV strain. B: VO caused a significant increase in LV wall strain, which was partially prevented by LOX inhibition. C: a ratio was established between wall stress and wall strain to obtain the end-diastolic stress-strain relationship (EDSSR), a marker of LV stiffness. Rats in the VO group had a significant increase in LV stiffness, and LOX inhibition partially reduced this increase. The following groups are shown: sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group). n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

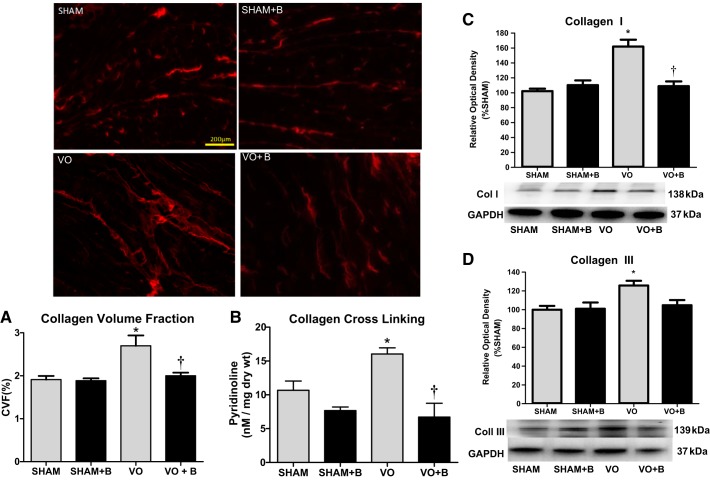

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced interstitial fibrosis.

The interstitial CVF was calculated from random picrosirius red-stained midventricular sections at 14 wk postsurgery (Fig. 4A). There were no significant changes in CVF in sham + B animals compared with sham animals. VO rat hearts, however, exhibited a significant increase in interstitial CVF (41% increase vs. sham rat hearts; Fig. 4A). These increases in collagen staining were not found in hearts of the VO + B group (Fig. 4A). Collagen levels in this rodent VO model do not reach levels found in models of hypertensive, infarction, or pressure overload, as there is a dramatic loss of collagen early in the remodeling process caused by VO that is followed by a gradual increase during disease progression. Our findings indicate that the LOX inhibitor prevented this increase, normalizing collagen deposition.

Fig. 4.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition prevented volume overload (VO)-induced interstital fibrosis and collagen cross-linking. Animals were divided into the following four groups: sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group). The collagen volume fraction (CVF) was calculated from picrosirius red-stained ventricular sections. Representative images are shown. CVF as well as protein measurements of collagen (Col) types I and III were significantly increased in the VO group (A). LOX inhibition completely prevented these increases (A, C, and D). Furthermore, collagen cross-linking was assessed via a pyridinoline assay. Although VO caused a significant increase collagen cross-linking, rats treated with LOX inhibitor had no change in cross-linking (B). n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced increases in collagen cross-linking.

PYD levels were used to assess LV collagen cross-links formed by LOX (Fig. 4B). There were no significant changes in PYD levels between sham and sham + B groups (Fig. 4B). There was a significant increase in LV PYD in the VO group compared with the sham group (43.5% increase vs. the sham group; Fig. 4B). This increase in collagen cross-linking was not present in the VO + B group (Fig. 4B). This normalization of collagen cross-linking is consistent with our finding of LV collagen staining that was not different from the sham group in the treated VO group.

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced increases in collagen types I and III.

There were no significant changes in the cardiac expression of collagen types I or III in the sham + B-treated group compared with the sham group (Fig. 4, C and D). Fourteen weeks of VO produced a significant increase in the LV expression of both collagen types I and III (58.4% and 26.7% increases vs. the sham group, respectively; Fig. 4, C and D). Compared with the VO group, the VO + B group had a significant decrease in collagen type I, which was similar to control levels (33% decrease vs. the VO group; Fig. 4C). Collagen type III expression in the VO + B group was not different from the sham group (Fig. 4D). As with cross-linking, these normal levels of LV collagen expression in the treated VO group coincide with our collagen staining results.

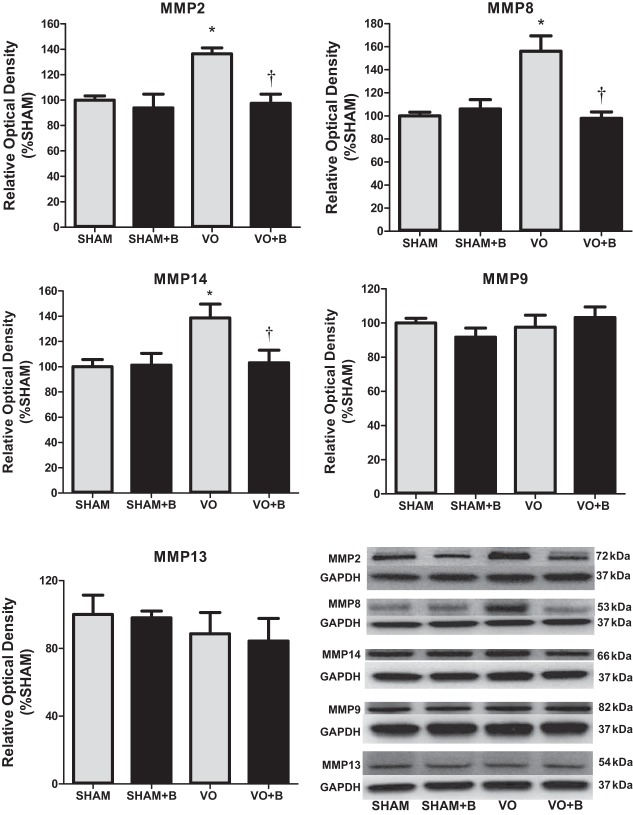

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced increases in MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-14.

For all LV MMP expression analyses, the band corresponding to the molecular weight of the active form was quantified. Various MMPs have been identified to play critical roles in pathological remodeling, including MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-14, MMP-9, and MMP-13. VO had no significant effects on LV MMP-9 and MMP-13 expression (Fig. 5). However, VO did cause a significant increase in MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-14 (36%, 56%, and 39% increases, respectively, vs. the sham group; Fig. 5). LOX inhibition prevented the increase of these MMPs in response to VO (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-14 may play a role in the cardioprotective effects of the LOX inhibitor.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analyses were used to assess protein expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13, and MMP-14. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition prevented the increases in MMP- 2, MMP-8, and MMP-14 caused by chronic volume overload (VO). There were no significant changes in MMP-9 or MMP-3. The following groups are shown: sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group). n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

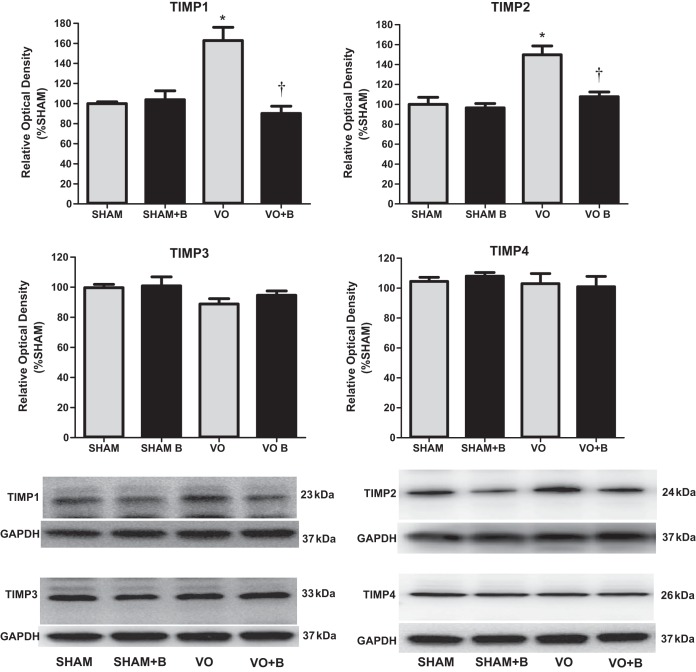

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced increases in TIMP-1 and TIMP-2.

Fourteen weeks of VO caused a significant increase in the LV protein expression of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 (63% and 50% increases, respectively, vs. the sham group; Fig. 6). There were no significant changes in TIMP-3 or TIMP-4 between any of the groups. The increased levels of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 were prevented by treatment with LOX inhibitor (Fig. 6). This reduction of TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in the treated VO group corresponds to an overall reduction in LV collagen expression and deposition.

Fig. 6.

Western blot analysis was used to assess protein expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, TIMP-2, TIMP-3, and TIMP-4. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition prevented volume overload (VO)-induced increases in TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. There were no differences between any of the groups for TIMP-3 and TIMP-4. The following groups are shown: sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group). n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

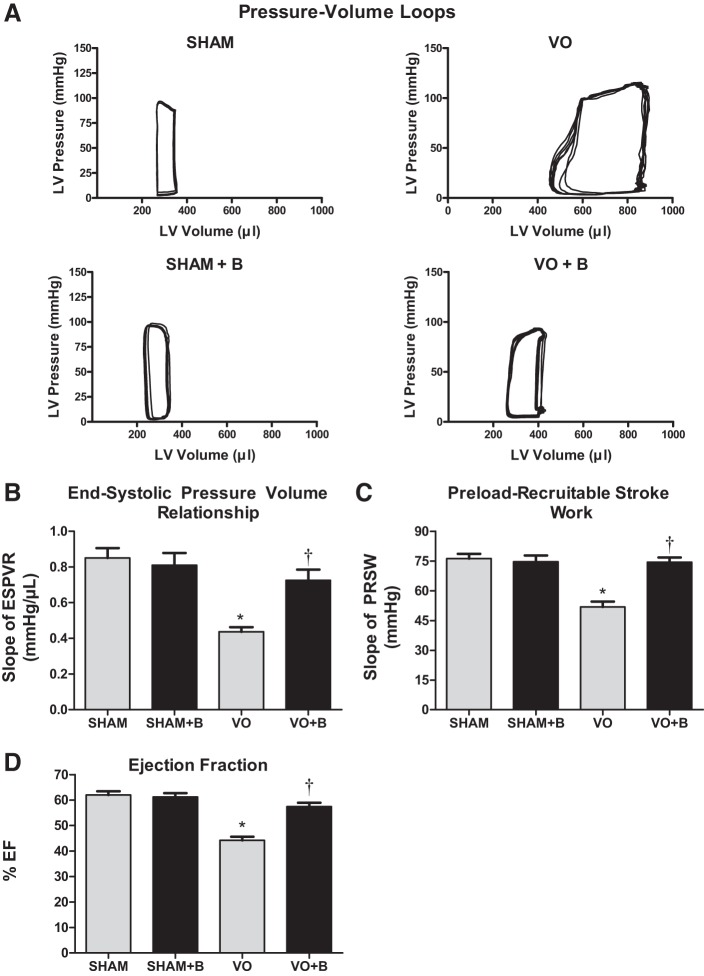

LOX inhibition prevented VO-induced decreases in cardiac function and contractility.

A cardiac catheter was used to establish LV pressure-volume loops at steady state for each of the groups. Representative images are shown in Fig. 7 and indicated LV dilatation (rightward shift) in both VO groups. The pressure-volume loops were then analyzed to provide measurements of heart rate, CO, EDV, ESV, EDP, ESP, stroke volume, ejection fraction, and arterial elastance. VO resulted in no significant changes in heart rate and ESP (Table 1). VO caused a significant increase in CO, EDV, ESV, EDP, and stroke volume (127%, 169%, 191%, 83%, and 132% increases, respectively, vs. the sham group; Table 1). Furthermore, VO induced a significant decrease in arterial elastance (70% decrease vs. the sham group; Table 1). Treatment with the LOX inhibitor completely prevented the changes in EDP, suggesting slowed progression of heart failure. The inhibitor only partially prevented the increases in CO, EDV, ESV, and SV and the decrease in arterial elastance (Table 1). Associated with the changes caused by VO was a significant decrease in ejection fraction (26% decrease vs. the sham group) and contractility, as assessed by the ESP-volume relationship and preload recruitable stroke work (Fig. 7). LOX inhibition preserved cardiac function, with the VO + B group exhibiting ejection fraction and contractility similar to those of the sham group. These cardioprotective effects of the LOX inhibitor appear to be related to a normalization of wall stress and reduction of progressive extracellular collagen remodeling.

Fig. 7.

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) inhibition maintained cardiac contractility and largely preserved function in volume overload (VO). A: representative left ventricular (LV) pressure-volume loops recorded at steady state for each group [sham surgery (sham group), VO surgery (VO) group, sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group)]. Chronic VO produced significant LV dilation, as indicated by a rightward shift of the pressure-volume loop compared with the sham group. Treatment with LOX inhibitor prevented much of this LV dilation. B and C: end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) and preload recruitable stroke work (PRSW) were determined by recording P-V loops at varying preload conditions (i.e., occlusion of the inferior vena cava) and used as indicators of LV contractility. Contractility was significantly reduced in the VO group along with ejection fraction (EF). Both indexes of contractility and EF were improved with LOX inhibition and were not significantly different than the sham control group. n = 4–8 animals/group. Statistical significance is denoted by *P < 0.05 vs. the sham group and †P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

Table 1.

Steady-state parameters of cardiac function as assessed by cardiac pressure-volume catheterization

| Sham Group | Sham + B Group | VO Group | VO + B Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate, beats/min | 327 ± 25 | 298 ± 32 | 304 ± 33 | 327 ± 30 |

| Cardiac output, ml/min | 59 ± 6 | 60 ± 6 | 134 ± 25* | 98 ± 18*† |

| End-diastolic volume, µl | 305 ± 14 | 330 ± 47 | 802 ± 115* | 504 ± 101*† |

| End-systolic volume, µl | 141 ± 19 | 128 ± 18 | 411 ± 46* | 263 ± 57*† |

| End-diastolic pressure, mmHg | 6 ± 1 | 17 ± 2 | 11 ± 3* | 9 ± 2* |

| End-systolic pressure, mmHg | 102 ± 13 | 101 ± 10 | 91 ± 10 | 91 ± 14 |

| Stroke volume, µl | 180 ± 15 | 211 ± 32 | 417 ± 58* | 297 ± 49*† |

| Arterial elastance, mmHg/µl | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.07* | 0.35 ± 0.11*† |

Values are means ± SE; n = 4–8 animals/group. Animals were divided into the following four groups: sham surgery (sham group), sham + LOX inhibitor (β-aminopropionitrile; sham + B group), VO surgery (VO) group, and VO + LOX inhibitor (VO + B group).

P < 0.05 vs. the sham group.

P < 0.05 vs. the VO group.

DISCUSSION

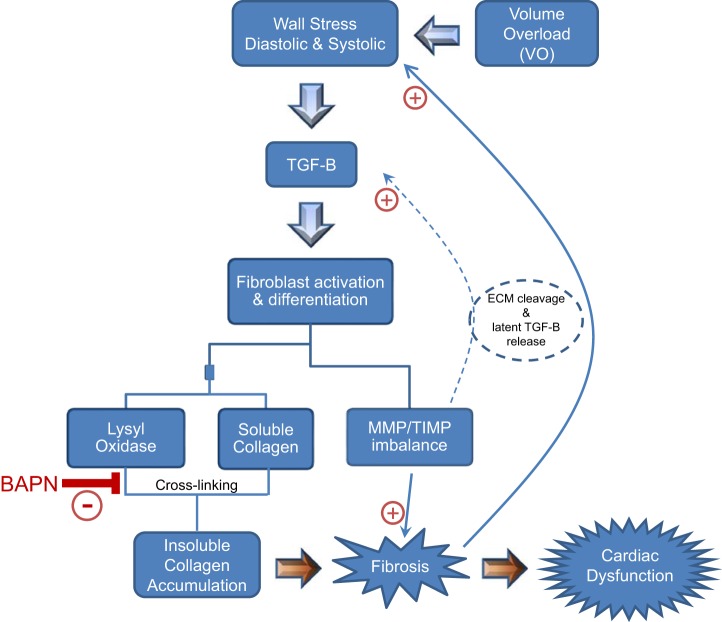

In this study, we focused on determining whether LOX inhibition initiated at 2 wk post-VO could prevent maladaptive ECM remodeling and subsequent cardiac dysfunction. Specifically, we assessed the impact of LOX inhibition on key mechanisms involved in collagen turnover. The major findings from this study are that LOX inhibition 1) prevented VO-induced increases in LV wall stress; 2) partially attenuated VO-induced ventricular hypertrophy; 3) completely blocked the increases in fibrotic proteins, including collagens, MMPs, and TIMPs; and 4) prevented the VO-induced decline in cardiac function (summarized in Fig. 8). We used a well-established rat model of VO to mimic the adverse ECM remodeling observed in human DCM. The chronological events that occur because of overload have been well documented by previous studies and confirmed by the present study (15, 25, 27). In the acute stages, hemodynamic overload produces an increase in wall stress, triggering compensatory mechanisms, including cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and remodeling of the ECM.

Fig. 8.

Overview of the pathogenesis of volume overload (VO)-induced fibrosis. VO is marked by significant increases in wall stress at both diastole and systole. This stress leads to the recruitment and activation of various growth factors, primarily transforming growth factor-β (TGF-B), which induces fibroblast differentiation and activation. Fibroblasts are converted to myofibroblasts, resulting in excessive secretion of matricellular proteins including lysyl oxidase (LOX) and soluble collagens. LOX cross-links collagen, yielding insoluble collagen, which is resistant to degradation by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), ultimately resulting in fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction. The imbalance between MMPs and their inhibitors [tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs)] causes further progression of disease. LOX inhibition limits the formation of cardiac fibrosis, allowing the appropriate breakdown of collagen by MMPs, which prevents adverse ventricular remodeling and associated dysfunction, halting the advancement of heart failure. BAPN, β-aminopropionitrile.

Collagen deposition in its initial stages is an adaptive response that aims to preserve tissue integrity and maintain normal ventricular function (52, 63). Paradoxically, various components of the fibrotic pathway form a positive feedback loop, which, if left unchecked, can lead to cardiac dysfunction and heart failure (45). For example, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β causes cardiac fibroblasts to differentiate into myofibroblasts (13, 39), which, in turn, produce more TGF-β and other inflammatory cytokines, propagating additional myofibroblast activation (30, 55). Myofibroblast activation also produces excess LOX as well as MMPs and TIMPs that play key roles in collagen turnover (15, 18, 49). The resulting decline in myocardial function secondary to the profibrotic phenotype increases wall stress, further perpetuating myofibroblast activation.

The synergistic effects of the proinflammatory and profibrotic responses induce a vicious cycle by which myofibroblasts are activated in excess, significantly increasing collagen deposition and accumulation in the matrix. Thus, therapeutics designed to disrupt this detrimental feedback loop by limiting inflammation, wall stress, myofibroblast activation, or even excessive deposition of collagen could constitute a potential therapeutic to halt the progression of pathological cardiac remodeling. Various studies have attempted to target upstream mediators of the fibrotic pathway, such as cardiac fibroblasts themselves; however, inhibition of cardiac fibroblast differentiation was associated with accelerated cardiac dilation and dysfunction (44). Another potential therapeutic target is TGF-β, because it is one of the most potent activators of myofibroblasts in response to stress. However, studies have shown that disruption of TGF-β signaling can accelerate the progression of heart failure (37), likely a result of TGF-β being a multifunctional growth factor involved in a wide range of functions that are essential for cell survival.

Upstream components of the fibrotic pathway have been proven to be poor therapeutic targets in a translational setting. We therefore shifted our focus to a more specific downstream fibrotic target, LOX. Collagen deposition and accumulation in the ECM is a key feature of fibrosis (66). However, soluble collagen or collagen that is not sufficiently cross-linked is very susceptible to degradation by MMPs (60). The LOX enzyme plays a key role in collagen cross-linking, converting soluble collagen into insoluble collagen, which is significantly more resistant to degradation (53). Multiple studies from our laboratory as well as others have demonstrated the detrimental effects of increased LOX on excessive collagen accumulation and fibrosis in patients and in models of cardiovascular disease (15, 16, 20, 36). López et al. (36) demonstrated that the expression of LOX is significantly increased in the fibrotic myocardium of patients with heart failure. Another study found that LOX induction in response to myocardial infarction promotes cardiac dysfunction, because LOX inhibition attenuated the decline in function (24). A previous study from our laboratory also demonstrated the detrimental role of excess LOX activity in adverse remodeling and cardiac dysfunction caused by chronic VO (15).

In addition to the key role that LOX plays in collagen regulation, MMPs and TIMPs are also critical for collagen turnover and maintenance. As hearts of rats with chronic VO have marked increases in LV collagen, we expected a decrease in expression of MMPs and an increase in TIMPs. However, our data showed that VO increased MMP-2, MMP-8, and MMP-14 as well as TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. The increases in TIMPs were expected, as TIMPs favor increases in collagen (1, 17). TIMP-1 is expressed in low levels in the healthy heart, but its expression is strongly induced in the failing heart (3, 48). Lindsay et al. (33) showed that increased expression of TIMP-1 is a marker of LV diastolic dysfunction and fibrosis. TIMP-1 has also been shown to have a MMP-independent influence on fibroblast behavior and ECM production (8). TIMP-2 is a unique member of the TIMP family. In addition to its key role in inhibiting MMPs, TIMP-2 selectively interacts with membrane-type MMPs to cleave and activate pro-MMPs; thus, TIMP-2 can both favor increases and decreases in MMP activity (4, 62).

Typically, studies have associated collagen accumulation with a decrease in MMP expression and activity. However, various studies have demonstrated that the relationship between MMPs and collagens is far more complex. A study by Ma et al. (38) showed that deletion of MMP-28 significantly impaired collagen deposition and cross-linking. Another study by Voorhees et al. (61) demonstrated that deletion of MMP-9 limited ECM turnover and decreased fibrotic remodeling. Multiple other studies have shown increased levels of MMPs in animal models of VO as well as in patients with DCM (54, 59). One study showed that patients with DCM exhibit increased expression of MMPs, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2, which was associated with collagen accumulation and fibrosis (59). Another study of patients with DCM showed that fibrosis in these patients was associated with increased levels of collagen types I and III, LOX, MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TGF-β (54). Furthermore, TIMPs can actually cleave and activate MMPs. For example, TIMP-2 interacts with MMP-14 (also known as membrane type 1-MMP), which activates pro-MMP-2 (4, 62). MMP-2 and MMP-14 cleave the ECM, releasing the ECM-bound latent TGF-β, which acts as a positive feedback mechanism to increase fibroblast activation (43). Therefore, the increases in both MMPs and TIMPs, in conjunction with LOX upregulation, contribute to the fibrotic state of the myocardium. Spinale et al. (56) showed that overexpression of MMP-1 results in severe myocardial fibrosis. Another study found that inhibition of MMPs resulted in decreases in ECM fibrosis and improved diastolic function (29). Although increases in MMPs are typically associated with collagen degradation and increases in TIMPs favor collagen accumulation, findings from several studies have proven that the interaction between MMPs, TIMPs, and the ECM is very complex.

It remains unclear whether a direct interaction between LOX and MMPs/TIMPs exists. However, our study suggests a possible link between the two as LOX inhibition completely attenuated VO-induced increases in both TIMPs and MMPs. This could be the result of a direct yet unknown effect of LOX on MMPs or an indirect effect, which is more probable based on our current understanding. LOX can promote TGF-β production through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, thus activating fibroblasts and stimulating production of MMPs and TIMPs (67). Furthermore, a byproduct of collagen cross-linking by LOX is hydrogen peroxide, which can promote oxidative stress, subsequently stimulating fibroblast activation (58). Finally, increases in LOX expression and activity during hemodynamic overload results in increased maturation and deposition of insoluble collagen fibers into the matrix. This can result in sustained increases in wall stress, as the ventricle begins to stiffen and can no longer adequately fill or eject blood. Sustained increases in wall stress also contribute to myofibroblast activation, significantly increasing the production of matricellular proteins. Therefore, once the adverse effects of increased LOX expression and activation are taken into account, the beneficial effects of LOX inhibition on normalizing protein levels of MMPs and TIMPs are less surprising.

Data from this study also support a link between excessive collagen deposition and sustained increases in wall stress, because VO caused a significant and sustained increase in systolic and diastolic wall stress, despite compensatory LV hypertrophy. However, LOX inhibition completely prevented this increased wall stress and associated volume-to-mass ratio. This normalization of wall stress blocked fibrosis and collagen accumulation and limited the stiffening of the LV, as indicated by the end-diastolic stress-strain relationship. Thus, maintenance of ECM integrity and diastolic function appears to limit the progression of adverse LV remodeling and dysfunction. LOX inhibition also completely prevented VO-induced cardiac dysfunction as evident by the normal contractility and ejection fraction in treated VO animals.

In support of the findings in the present study, similar observations have been made in the aging myocardium. Altered loading conditions with age have been associated with cardiac fibroblast proliferation and subsequent interstitial fibrosis (14, 35, 40), making diastolic heart failure the leading cause of hospitalization in elderly patients (2). Progressive increases in LV collagen with age are independent of hypertension (32) and associated with increased wall stress and contractile dysfunction (11, 32). Human studies have shown significant increases in collagen content in aged hearts (22). Of particular interest, circulating MMP-2, MMP-7, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 increase with age and correlate with diastolic dysfunction in nondiseased elderly human hearts (6). LOX expression and activity have been previously reported to increase with age (36) by means of TGF-β (5). Rosin et al. (51) demonstrated that LOX inhibition in aged mice significantly decreased total myocardial collagen and attenuated increases in the ratio of early to late peak velocity (E/A), a measure of diastolic dysfunction, compared with levels observed in younger mice. The clinical utility of LOX inhibition for the prevention of age-related cardiac and vascular dysfunction appears promising yet uncertain.

Future studies are warranted to assess further the mechanism by which LOX inhibition improves systolic function. Overall, the present study demonstrated that LOX inhibition completely prevented VO-induced increases in collagen accumulation. Furthermore, LOX inhibition seemed to disrupt the vicious positive feedback loop that persistently activates myofibroblasts and leads to excessive deposition of matricellular proteins and stiffening of the matrix. Ultimately, LOX inhibition prevented the VO-induced decline in diastolic and systolic function, conferring cardioprotective effects. A limitation of this study is that the LOX inhibitor was administered systemically; therefore, the inhibitor did not specifically target the heart and may have affected other organ systems. Also, the effects of LOX inhibition were studied at one end point where we found dramatic cardioprotection with significant changes in MMP and TIMP expression. It is possible that these effects on MMPs and TIMPs were secondary to the improved functional state of the myocardium and not a direct effect of LOX inhibition.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grants 16GRNT30440008 (to J. Gardner) and 16PRE29150010 (to E. El Hajj) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 1-F31-HL-134263 (to E. El Hajj).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.D.G. conceived and designed research; E.C.E.H., M.C.E.H., V.K.N., and J.D.G. performed experiments; E.C.E.H., M.C.E.H., V.K.N., and J.D.G. analyzed data; M.C.E.H. and J.D.G. interpreted results of experiments; E.C.E.H., M.C.E.H., and J.D.G. prepared figures; E.C.E.H., M.C.E.H., and J.D.G. drafted manuscript; E.C.E.H., M.C.E.H., and J.D.G. edited and revised manuscript; E.C.E.H. and J.D.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arpino V, Brock M, Gill SE. The role of TIMPs in regulation of extracellular matrix proteolysis. Matrix Biol 44-46: 247–254, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barasch E, Gottdiener JS, Aurigemma G, Kitzman DW, Han J, Kop WJ, Tracy RP. Association between elevated fibrosis markers and heart failure in the elderly: the cardiovascular health study. Circ Heart Fail 2: 303–310, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.828343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton PJ, Birks EJ, Felkin LE, Cullen ME, Koban MU, Yacoub MH. Increased expression of extracellular matrix regulators TIMP1 and MMP1 in deteriorating heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 22: 738–744, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(02)00557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernardo MM, Fridman R. TIMP-2 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2) regulates MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase-2) activity in the extracellular environment after pro-MMP-2 activation by MT1 (membrane type 1)-MMP. Biochem J 374: 739–745, 2003. doi: 10.1042/bj20030557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biernacka A, Frangogiannis NG. Aging and cardiac fibrosis. Aging Dis 2: 158–173, 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnema DD, Webb CS, Pennington WR, Stroud RE, Leonardi AE, Clark LL, McClure CD, Finklea L, Spinale FG, Zile MR. Effects of age on plasma matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). J Card Fail 13: 530–540, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowers SL, Banerjee I, Baudino TA. The extracellular matrix: at the center of it all. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 474–482, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brew K, Nagase H. The tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs): an ancient family with structural and functional diversity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803: 55–71, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brower GL, Gardner JD, Forman MF, Murray DB, Voloshenyuk T, Levick SP, Janicki JS. The relationship between myocardial extracellular matrix remodeling and ventricular function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 30: 604–610, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 65: 40–51, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capasso JM, Palackal T, Olivetti G, Anversa P. Severe myocardial dysfunction induced by ventricular remodeling in aging rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H1086–H1096, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaturvedi RR, Herron T, Simmons R, Shore D, Kumar P, Sethia B, Chua F, Vassiliadis E, Kentish JC. Passive stiffness of myocardium from congenital heart disease and implications for diastole. Circulation 121: 979–988, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.850677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H, Yang WW, Wen QT, Xu L, Chen M. TGF-beta induces fibroblast activation protein expression; fibroblast activation protein expression increases the proliferation, adhesion, and migration of HO-8910PM (corrected). Exp Mol Pathol 87: 189–194, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Castro Brás LE, Toba H, Baicu CF, Zile MR, Weintraub ST, Lindsey ML, Bradshaw AD. Age and SPARC change the extracellular matrix composition of the left ventricle. BioMed Res Int 2014: 810562, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/810562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Hajj EC, El Hajj MC, Ninh VK, Bradley JM, Claudino MA, Gardner JD. Detrimental role of lysyl oxidase in cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 109: 17–26, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Hajj EC, El Hajj MC, Ninh VK, Gardner JD. Cardioprotective effects of lysyl oxidase inhibition against volume overload-induced extracellular matrix remodeling. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 241: 539–549, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1535370215616511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Hajj EC, El Hajj MC, Voloshenyuk TG, Mouton AJ, Khoutorova E, Molina PE, Gilpin NW, Gardner JD. Alcohol modulation of cardiac matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs favors collagen accumulation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 448–456, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acer.12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan D, Takawale A, Lee J, Kassiri Z. Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 5: 15, 2012. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman BR, Bade ND, Riggin CN, Zhang S, Haines PG, Ong KL, Janmey PA. The (dys)functional extracellular matrix. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853, 11 Pt B: 3153–3164, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galán M, Varona S, Guadall A, Orriols M, Navas M, Aguiló S, de Diego A, Navarro MA, García-Dorado D, Rodríguez-Sinovas A, Martínez-González J, Rodriguez C. Lysyl oxidase overexpression accelerates cardiac remodeling and aggravates angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy. FASEB J 31: 3787–3799, 2017. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601157RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardner JD, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Effects of dietary phytoestrogens on cardiac remodeling secondary to chronic volume overload in female rats. J Appl Physiol 99: 1378–1383, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01141.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gazoti Debessa CR, Mesiano Maifrino LB, Rodrigues de Souza R. Age related changes of the collagen network of the human heart. Mech Ageing Dev 122: 1049–1058, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(01)00238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerdes AM, Kellerman SE, Moore JA, Muffly KE, Clark LC, Reaves PY, Malec KB, McKeown PP, Schocken DD. Structural remodeling of cardiac myocytes in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 86: 426–430, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.González-Santamaría J, Villalba M, Busnadiego O, López-Olañeta MM, Sandoval P, Snabel J, López-Cabrera M, Erler JT, Hanemaaijer R, Lara-Pezzi E, Rodríguez-Pascual F. Matrix cross-linking lysyl oxidases are induced in response to myocardial infarction and promote cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res 109: 67–78, 2016. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchinson KR, Stewart JA JR, Lucchesi PA. Extracellular matrix remodeling during the progression of volume overload-induced heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 564–569, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HE, Dalal SS, Young E, Legato MJ, Weisfeldt ML, D’Armiento J. Disruption of the myocardial extracellular matrix leads to cardiac dysfunction. J Clin Invest 106: 857–866, 2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi M, Machida N, Tanaka R, Yamane Y. Effects of beta-blocker on left ventricular remodeling in rats with volume overload cardiac failure. J Vet Med Sci 70: 1231–1237, 2008. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 71: 549–574, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishnamurthy P, Peterson JT, Subramanian V, Singh M, Singh K. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases improves left ventricular function in mice lacking osteopontin after myocardial infarction. Mol Cell Biochem 322: 53–62, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9939-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leask A. TGFbeta, cardiac fibroblasts, and the fibrotic response. Cardiovasc Res 74: 207–212, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li YY, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM. Proinflammatory cytokines regulate tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases and disintegrin metalloproteinase in cardiac cells. Cardiovasc Res 42: 162–172, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Lopez EF, Jin Y, Van Remmen H, Bauch T, Han HC, Lindsey ML. Age-related cardiac muscle sarcopenia: Combining experimental and mathematical modeling to identify mechanisms. Exp Gerontol 43: 296–306, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindsay MM, Maxwell P, Dunn FG. TIMP-1: a marker of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and fibrosis in hypertension. Hypertension 40: 136–141, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000024573.17293.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsey ML, Gannon J, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ, Rabkin E, Lopresti-Morrow L, Crawford J, Black S, Libby P, Mitchell PG, Lee RT. Selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces left ventricular remodeling but does not inhibit angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 105: 753–758, 2002. doi: 10.1161/hc0602.103674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsey ML, Goshorn DK, Squires CE, Escobar GP, Hendrick JW, Mingoia JT, Sweterlitsch SE, Spinale FG. Age-dependent changes in myocardial matrix metalloproteinase/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase profiles and fibroblast function. Cardiovasc Res 66: 410–419, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.López B, González A, Hermida N, Valencia F, de Teresa E, Díez J. Role of lysyl oxidase in myocardial fibrosis: from basic science to clinical aspects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1–H9, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00335.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas JA, Zhang Y, Li P, Gong K, Miller AP, Hassan E, Hage F, Xing D, Wells B, Oparil S, Chen YF. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling induces left ventricular dilation and dysfunction in the pressure-overloaded heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H424–H432, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00529.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma Y, Halade GV, Zhang J, Ramirez TA, Levin D, Voorhees A, Jin YF, Han HC, Manicone AM, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-28 deletion exacerbates cardiac dysfunction and rupture after myocardial infarction in mice by inhibiting M2 macrophage activation. Circ Res 112: 675–688, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng XM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 325–338, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meschiari CA, Ero OK, Pan H, Finkel T, Lindsey ML. The impact of aging on cardiac extracellular matrix. Geroscience 39: 7–18, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-9959-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miner EC, Miller WL. A look between the cardiomyocytes: the extracellular matrix in heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc 81: 71–76, 2006. doi: 10.4065/81.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narayan S, Janicki JS, Shroff SG, Pick R, Weber KT. Myocardial collagen and mechanics after preventing hypertrophy in hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 2: 675–682, 1989. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.9.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newby AC. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate migration, proliferation, and death of vascular smooth muscle cells by degrading matrix and non-matrix substrates. Cardiovasc Res 69: 614–624, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozhan G, Weidinger G. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in heart regeneration. Cell Regen (Lond) 4: 3, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s13619-015-0017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker MW, Rossi D, Peterson M, Smith K, Sikström K, White ES, Connett JE, Henke CA, Larsson O, Bitterman PB. Fibrotic extracellular matrix activates a profibrotic positive feedback loop. J Clin Invest 124: 1622–1635, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI71386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelouch V, Dixon IM, Golfman L, Beamish RE, Dhalla NS. Role of extracellular matrix proteins in heart function. Mol Cell Biochem 129: 101–120, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00926359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Picard F, Brehm M, Fassbach M, Pelzer B, Scheuring S, Küry P, Strauer BE, Schwartzkopff B. Increased cardiac mRNA expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and its inhibitor (TIMP-1) in DCM patients. Clin Res Cardiol 95: 261–269, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0373-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piek A, de Boer RA, Silljé HH. The fibrosis-cell death axis in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 21: 199–211, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9536-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polyakova V, Hein S, Kostin S, Ziegelhoeffer T, Schaper J. Matrix metalloproteinases and their tissue inhibitors in pressure-overloaded human myocardium during heart failure progression. J Am Coll Cardiol 44: 1609–1618, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinhardt D, Sigusch HH, Hensse J, Tyagi SC, Körfer R, Figulla HR. Cardiac remodelling in end stage heart failure: upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) irrespective of the underlying disease, and evidence for a direct inhibitory effect of ACE inhibitors on MMP. Heart 88: 525–530, 2002. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosin NL, Sopel MJ, Falkenham A, Lee TD, Légaré JF. Disruption of collagen homeostasis can reverse established age-related myocardial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 185: 631–642, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segura AM, Frazier OH, Buja LM. Fibrosis and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 19: 173–185, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegel RC, Pinnell SR, Martin GR. Cross-linking of collagen and elastin. Properties of lysyl oxidase. Biochemistry 9: 4486–4492, 1970. doi: 10.1021/bi00825a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sivakumar P, Gupta S, Sarkar S, Sen S. Upregulation of lysyl oxidase and MMPs during cardiac remodeling in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem 307: 159–167, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9595-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res 105: 1164–1176, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spinale FG, Escobar GP, Mukherjee R, Zavadzkas JA, Saunders SM, Jeffords LB, Leone AM, Beck C, Bouges S, Stroud RE. Cardiac-restricted overexpression of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase in mice: effects on myocardial remodeling with aging. Circ Heart Fail 2: 351–360, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.844845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spinale FG, Wilbur NM. Matrix metalloproteinase therapy in heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 11: 339–346, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s11936-009-0034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor MA, Amin JD, Kirschmann DA, Schiemann WP. Lysyl oxidase contributes to mechanotransduction-mediated regulation of transforming growth factor-β signaling in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia 13: 406–418, 2011. doi: 10.1593/neo.101086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas CV, Coker ML, Zellner JL, Handy JR, Crumbley AJ III, Spinale FG. Increased matrix metalloproteinase activity and selective upregulation in LV myocardium from patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 97: 1708–1715, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.17.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Slot-Verhoeven AJ, van Dura EA, Attema J, Blauw B, Degroot J, Huizinga TW, Zuurmond AM, Bank RA. The type of collagen cross-link determines the reversibility of experimental skin fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1740: 60–67, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voorhees AP, DeLeon-Pennell KY, Ma Y, Halade GV, Yabluchanskiy A, Iyer RP, Flynn E, Cates CA, Lindsey ML, Han HC. Building a better infarct: modulation of collagen cross-linking to increase infarct stiffness and reduce left ventricular dilation post-myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 85: 229–239, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Juttermann R, Soloway PD. TIMP-2 is required for efficient activation of proMMP-2 in vivo. J Biol Chem 275: 26411–26415, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber KT. Targeting pathological remodeling: concepts of cardioprotection and reparation. Circulation 102: 1342–1345, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.12.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber KT, Janicki JS, Reeves RC, Hefner LL. Factors influencing left ventricular shortening in isolated canine heart. Am J Physiol 230: 419–426, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weber KT, Sun Y, Tyagi SC, Cleutjens JP. Collagen network of the myocardium: function, structural remodeling and regulatory mechanisms. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 279–292, 1994. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med 18: 1028–1040, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nm.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang J, Savvatis K, Kang JS, Fan P, Zhong H, Schwartz K, Barry V, Mikels-Vigdal A, Karpinski S, Kornyeyev D, Adamkewicz J, Feng X, Zhou Q, Shang C, Kumar P, Phan D, Kasner M, López B, Diez J, Wright KC, Kovacs RL, Chen PS, Quertermous T, Smith V, Yao L, Tschöpe C, Chang CP. Targeting LOXL2 for cardiac interstitial fibrosis and heart failure treatment. Nat Commun 7: 13710, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]