Abstract

Background

Elevated levels of irritability are reported to occur in a number of neurological conditions, including Huntington's disease (HD), a genetic neurodegenerative disorder. Snaith's Irritability Scale (SIS) is used within HD research, but no psychometric evaluation of this instrument has previously been undertaken. Therefore, the current study aimed to analyze the factor structure of this scale among an HD population.

Methods

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were used to examine the structural properties of SIS using responses from 1,264 HD gene expansion carriers, across 15 European countries, who were engaged in the REGISTRY 3 study.

Results

An exploratory factor analysis of a subsample of the data suggested a two‐factor interpretation of the data comprising “temper” and “self‐harm.” Eight possible models were tested for goodness of fit using confirmatory factor analysis. Two bifactor models, testing general and group factors in the structure of the scale, provided an equivocal “good” fit to the data. The first comprised a general irritability factor and two group factors (as originally proposed using SIS): outward irritability and inward irritability. The second comprised a general irritability factor and two group factors (as proposed by the exploratory factor analysis): temper and self‐harm. The findings from both models suggested that the loadings of items were higher on the general factor.

Conclusions

Bifactor models are proposed to best consider the structure of the SIS, with findings suggesting that an overall score should be used to measure irritability within HD populations.

Keywords: factor analysis, Huntington disease, SIS, irritability, Snaith

Irritability is often reported in people with a variety of neurological conditions, including Parkinson's disease,1 Huntington's disease (HD),2 Gilles de la Tourette syndrome,3 and traumatic brain injury.4 Irritability is understood as a temporary mood state characterized by impatience, intolerance, and poorly controlled anger;5 it may result in verbal or behavioral outbursts, although the mood may be present without these observed manifestations, is subjectively unpleasant, and can be brief or prolonged.6

Although irritability has not been the subject of significant empirical research across both clinical and normative samples, it warrants further study given that it has important clinical implications. For example, among people with mental health difficulties, irritability is associated with poorer quality of life, higher suicidal ideation, and a greater history of suicide attempts.7 Also, those who report irritable mood states are more likely to experience mood disorders, anxiety and impulse‐control disorders, drug dependence, and a higher prevalence of fatigue.8 Given these implications, it is important that clinicians and researchers accurately identify and monitor irritability in order for complex problems to be understood and managed effectively.7

In terms of HD, an inherited movement disorder with cognitive decline and emotional difficulties, irritability is reported across all stages of the disease, including the premotor manifest period (i.e., before clinical diagnosis of HD).9, 10, 11 The prevalence of irritability among HD gene expansion carriers varies across studies from 38% to 73%.2, 12 Furthermore, although irritability can correlate with other emotional difficulties in HD, such as depression and anxiety,13 it demonstrates a distinct pattern of increasing severity among premotor symptomatic carriers as they become closer to motor onset, compared with these other difficulties.11, 14, 15 Moreover, among people with HD, irritability is more closely related to aggression than other difficulties, such as depression, apathy, and anxiety.12, 16, 17, 18, 19 This relationship with aggression, and thus the potential risk of causing harm to others, has highlighted irritability as a clinically and socially important construct to be studied among those with HD. Such consequences of irritable mood may also impact on provision of care, increasing the likelihood of HD patients having to move into a nursing home, rather than being managed in the community.20, 21 Therefore, the interpersonal manifestations of heightened irritability may have a deleterious effect on caregivers,22 resulting in protective factors, such as social support and positive relationships, becoming jeopardized. In addition to the risk of causing harm to others, there is the potential that facets of irritability in HD may also have associations with the risk of causing harm to the self,23 though, as yet, this has received limited attention. For example, irritability has been found to be higher among HD gene expansion carriers with suicidal ideation than among those without,23 a finding consistent with studies of those with mental health difficulties.5 However, no predictive relationship between irritability and suicidality has been identified,23 but this may be partly explained by the measure of irritability used, which has focused on outward conceptualisations of irritability.23 Further understanding of the structural relationship of different aspects of irritability may help inform future studies examining relationships between suicide risk and irritability factors (i.e., both outward and inward expressions of irritable mood5).

Within the literature available, irritability has most commonly been measured among HD gene expansion carriers using interviewer‐rated assessments, such as the Problem Behaviors Assessment‐HD18 and the United Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS).24 Although interviewer‐based measures are useful in enabling assessment of mood among HD patients who may not be fully aware of their difficulties, brief self‐report assessments offer benefits, such as being quick and easy to administer, with no specific training required for administration. Self‐assessment may also reveal information that some individuals may find difficult to disclose in more‐formal interview settings. Currently, a self‐reported measure of irritability used within the field of HD research is the irritability subscale contained within the Irritability, Depression, Anxiety Scale,5 which has been used independently as an eight‐item measure of irritability and is also referred to as the Snaith Irritability Scale (SIS).25, 26 Furthermore, the SIS is the only self‐report measure of irritability currently used in large‐scale longitudinal international HD studies, for example, REGISTRY (http://www.euro-hd.net/html/registry) and ENROLL‐HD (https://www.enroll-hd.org/).

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has recently highlighted the importance of validation studies for HD patient‐reported instruments, especially when considering outcome measures for clinical trials;27 therefore, it is necessary for psychometrically informed studies to be undertaken. In terms of the psychometric structure of the SIS, the recommended scoring of the scale comprises two factors: four irritability items within the scale measuring outwardly expressed irritability and the other four examining inwardly expressed irritability.5 However, psychometric validation studies of this instrument in clinical samples are limited, and no study has examined the psychometric properties of this scale within an HD population, including testing the assumption of the original scale as a two‐factor model.

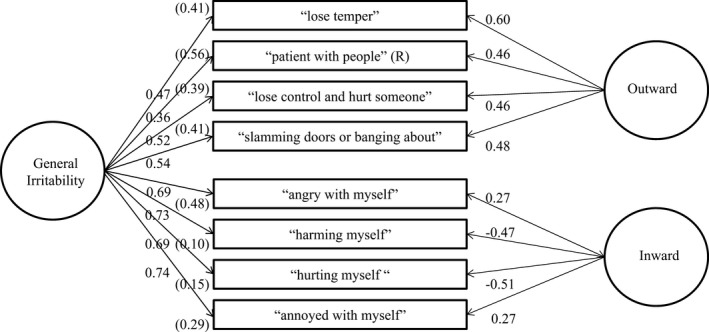

In the field of psychometrics, higher‐order solutions present alternative theoretical approaches for examination of the factor structure of a scale. Rather than simply identifying the number of factors that emerge from an analysis of test items, higher‐order factor analytical models introduce the concept of a general construct and consider its relation to group factors formed from the items. Within this perspective, the central theoretical difference focuses on the presence of a general factor informing our understanding of the constructs being considered. Within higher‐order factor models, typically two solutions are considered: second‐order factor and bifactor models.28 Second‐order factor models present the relationship between the factors and items portrayed using a hierarchical structure, with the variance of all items (at the bottom of the hierarchy) being explained by group factors (e.g., inward vs. outward irritability) and the group factor variance being explained by a general latent factor (e.g., general irritability). With a bifactor model, the explained variance between the items is simultaneously considered between both the general and group factors. First, a single common construct (e.g., general irritability) is suggested to explain the shared variance between all of the items. Second, to recognize the multidimensionality of the construct, group factors are suggested (e.g., inward versus outward irritability), to also explain some of the shared variance between the items (see Fig. 1 for an illustration).

Figure 1.

Standardized loadings (with measurement error terms in parenthesis) for the eight‐item SIS bifactor structure with general irritability and outward and inward group factors.

Inclusion of these models in understanding the factor structure of the SIS, if proved useful, may help inform treatment approaches. For example, in terms of the use of the SIS as an assessment tool, interventions could be informed by consideration of inward and outward irritability as separate constructs, with potential etiological differences between the two. In contrast, within a higher‐order solution, the treatment would additionally be informed by consideration of the etiology of a general factor of irritability. There is good reason to propose an underlying general factor of irritability in HD attributed to the genetic heritability of the disease. A number of processes could underpin a general irritability factor (that encompasses both outward or inward manifestations of irritability) that include the direct neuropathological changes,29 cognitive appraisals regarding having HD,30 and frustrations concerning the overwhelming impact that the disease has on one's life.31 Consequently, psychometric analysis using higher‐order models may help inform how interventions may be targeted, in terms of understanding whether there are separate or related pathways that underpin the different facets of irritability among people with HD.

The aim of the current study was to conduct the first factor analysis study of the SIS within a large HD sample to explore the latent structure within this population and evaluate the structure against different proposed models of the SIS.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Measures

Data were obtained from the European HD Network (EHDN) following approval from the Scientific and Bioethics Advisory Committee. Our data request included all SIS assessments available from the REGISTRY 3 project. REGISTRY is a multinational, observational study examining the natural history of HD. Because the initial data set included longitudinal data involving repeated assessments of annual visits using the same participants (n = 3,234), we excluded all except the participants’ last visit (n = 1,474). We also excluded 210 respondents with incomplete irritability assessments, missing Total Functional Capacity (TFC) scores (measure of functional ability, ranging from 0 to 13, with lower scores reflecting reduced capacity to undertake daily living activities) or Total Motor Scores (TMS; measure of different motor tasks, with higher scores indicating greater motor impairment) from the UHDRS, and those whose cytosine‐adenine‐guanine repeat was ≤39 (to exclude those without the HD gene expansion).

The final cross‐sectional sample comprised 1,264 participants with the HD gene expansion, who completed the SIS between 24 June 2011 and 20 February 2014, from the following European countries (n in brackets): Austria (12), Belgium (8), Czech Republic (3), Finland (4), France (303), Germany (287), Italy (38), Netherlands (97), Norway (17), Poland (228), Portugal (70), Spain (134), Sweden (5), Switzerland (7), and UK (51). Across all countries, participants gave written informed consent according to the full ethical approvals required for the REGISTRY study. Of these participants, 52.8% were female and the mean age of the sample at time of visit was 48.71 years (standard deviation [SD] = 13.73; range, 14–88).

To describe the clinical profile of the sample, we examined TFC scores, disease stage32 and the TMS scores from the UHDRS.24 In terms of the profile of the sample, the TFC mean score was 8.54 (SD = 3.94; range, 0–13). Across the total sample, the breakdown of participants in each stage of HD was as follows (n in brackets): Premanifest (250), Stage I, with TFC scores of 11 to 13 (276), Stage II with TFC scores 7 to 10 (311), Stage III with scores 3 to 6 (315), Stage IV with TFC scores of 1 or 2 (101), and Stage V with a TFC score of 0 (11). The mean TMS score was 33.55 (SD = 24.50; range, 0–108).

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

The number of participants (632) to variables (8) ratio exceeded the recommended ratio for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of 10:1, with a minimum number of participants of 150.33 Bartlett's test confirmed an EFA was appropriate for the sample (χ 2 [28] = 15,544.21; P < 0.001), and a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (0.83) indicated sufficient participants: item ratio of 79:1. Preliminary analyses of the scores on the items of the SIS demonstrated that seven items fell outside the criterion for a univariate normal distribution of between ±1.34 Therefore, a principal‐axis EFA was conducted.35

Parallel analysis (where eigenvalues are compared to those calculated from purely random data) is the most appropriate and accurate method for determining the number of factors.35, 36 Within this analysis, the third eigenvalue (3.60, 1.13 and 0.77) failed to exceed the third mean eigenvalue (1.17, 1.11, and 1.06) calculated from 1,000 generated datasets with 501 cases and eight variables. This suggested a two‐factor solution (with the factors accounting for 44.94% and 14.22% of the variance, respectively). Loadings were assessed against the thresholds of 0.32 (poor), 0.45 (fair), 0.55 (good), 0.63 (very good), and 0.71 (excellent)37 and are presented in Table 1. In terms of loadings above 0.45, the first factor comprises six items that represent “temper,” encompassing inward and outward expressions of irritability, such as “lose temper” and “feel like slamming doors” (items are abbreviated because of copyright). The second factor comprises two items referring to self‐harm, “feel like harming myself” and “hurting myself occurs to me.”

Table 1.

EFA (principal axis factoring extraction with promax rotation) of the eight irritability items

| Factor | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 1. “lose temper” | 0.82 | −0.10 |

| 2. ”patient with people” (R) | 0.57 | −0.06 |

| 3. “angry with myself” | 0.49 | 0.22 |

| 4. “harming myself” | 0.03 | 0.73 |

| 5. “hurting myself” | −0.08 | 0.86 |

| 6. “lose control and hurt someone” | 0.59 | 0.01 |

| 7. “feel like slamming doors or banging about” | 0.69 | −0.01 |

| 8. “annoyed with myself” | 0.50 | 0.24 |

Key: (R) = reversed.

A correlation between the two factors was r = 0.57, suggesting shared variance of 32.5%. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients38 for: the eight items was α = 0.82; for the six items, α = 0.80; and for the two items, α = 0.76. These statistics exceed the criterion of α > 0.70 as “good.”39, 40

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To explore the structural validity of the SIS, a series of comparisons using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS 22 software with the second sample data. A focus of CFA is to demonstrate the incremental value of proposed models.41 Eight possible models were tested for goodness of fit. The first two were unidimensional models representing an underlying latent factor structure of general irritability (1) for the eight items of the SIS and (2) the six items that loaded on the first factor in the EFA. The third model tested was the proposed original two‐factor structure for the SIS, inward and outward factors. The fourth model was the proposed two‐factor structure resulting from our EFA of the SIS, temper and self‐harm factors. The remaining models tested higher‐order solutions for the data. The fifth and sixth models were second‐order factor models in which general irritability formed the top level of a hierarchy in which inward versus outward (model 5) and temper and self‐harm irritability (model 6) were group factors. The seventh and eighth models were higher‐order bifactor models proposing a single common construct (general irritability) while recognizing the multidimensionality of the construct; inward and outward (model 7) and temper and self‐harm irritability (model 8).

To assess the goodness of fit of the data, we used six statistics recommended by Hu and Bentler42 and Kline:43 the chi‐square (χ 2); the relative chi‐square (CMIN/DF); the comparative fit index (CFI); the non‐normed fit index (NNFI); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The following criteria was used to assess whether the model fit to the data was adequate (noting that the chi‐square test was likely to be significant because of large sample size):44 (1) CMIN/DF must fall between 5 and 2 to be “acceptable” and be less than 2 to be “good”; (2) that the CFI and NNFI should exceed 0.90 to be “acceptable” and exceed 0.95 to be “good”; (3) that the RMSEA should not exceed 0.08 to be “acceptable”; and be under 0.06 to be “good”; and (4) SRMR values less than 0.08 are “acceptable” and less than 0.05 to be “good.”42, 43, 45

The goodness‐of‐fit statistics for the eight models are presented in Table 2. For the unidimensional, two‐factor and second‐order models, the large majority of the goodness‐of‐fit statistics did not meet all the aforementioned criteria for acceptability, and therefore the models did not present an adequate explanation of the data. The bifactor models presented relative chi‐square and RMSEA statistics that were acceptable and CFI, NNFI, and SRMR goodness‐of‐fit statistics all exceeding the “good” criteria. The findings for the bifactor models also demonstrate improved CFI statistics over the other models, as indicated by changes in CFI (ΔCFI) being >0.01.

Table 2.

CFA fit statistics for the different models proposed for the SIS

| χ 2 | df | P | CMIN/DF | CFI | NNFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unidimensional (eight items) | 475.31 | 20 | <0.000 | 23.77 | 0.753 | 0.654 | 0.190 | 0.088 |

| Unidimensional (six items) | 150.62 | 9 | <0.000 | 16.74 | 0.875 | 0.791 | 0.158 | 0.067 |

| Two factors (inward/outward) | 265.31 | 19 | <0.000 | 13.96 | 0.866 | 0.803 | 0.129 | 0.143 |

| Two factors (temper/self‐harm) | 265.31 | 19 | <0.000 | 13.96 | 0.866 | 0.803 | 0.129 | 0.143 |

| Second‐order (inward/outward) | 265.31 | 19 | <0.000 | 13.96 | 0.866 | 0.803 | 0.143 | 0.086 |

| Second‐order (temper/self‐harm) | 181.81 | 19 | <0.000 | 9.57 | 0.912 | 0.870 | 0.117 | 0.060 |

| Bifactor (inward/outward) | 41.34 | 12 | <0.000 | 3.45 | 0.983 | 0.963 | 0.062 | 0.025 |

| Bifactor (temper/self‐harm) | 41.34 | 12 | <0.000 | 3.45 | 0.984 | 0.963 | 0.062 | 0.025 |

The standardized loadings (with measurement error terms in parenthesis) for both suggested bifactor structures with general and group factors are presented in Figures 1 and 2. A number of statistics were used to examine the relative relationship between the general and group factors. In terms of the original two factors of the SIS (inward and outward), the variance accounted for the general factor in this model was 64.2%, with inward and outward group factors explaining 13.7% and 22.1%, respectively. In terms of salience of loading on the factors, the mean loadings were higher on the general factor (m = 0.59) than on the group factors (m = 0.41). The more‐traditional reliability estimates for the general and group factors were good: general factor α = 0.83; omega total = 0.89; outward group factor, α = 0.78; omega total = 0.79; inward group factor, α = 0.77; omega total = 0.86. However, the omega hierarchical coefficient, which estimates the reliability with the effect of all the other factors removed, was low for the group factors (outward, omega hierarchical = 0.38; inward, omega hierarchical = 0.17) and was only acceptable for the general irritability factor (omega hierarchical = 0.71).

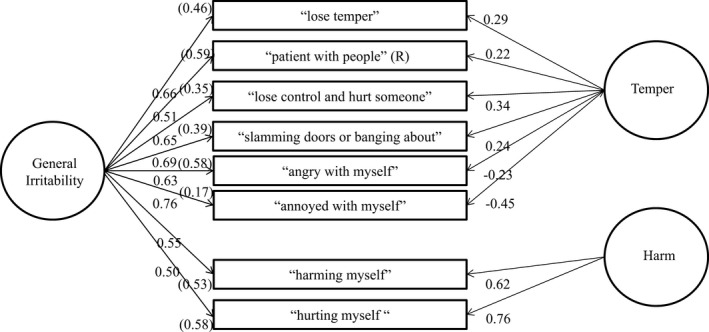

Figure 2.

Standardized loadings (with measurement error terms in parenthesis) for the eight‐item SIS bifactor structure with general irritability and temper and self‐harm group factors.

The findings were similar in terms of the scoring derived from the EFA (i.e., temper and self‐harm). Variance accounted for the general factor in this model was 67.3%, with inward and outward group factors explaining 12.1% and 20.5%, respectively. In terms of salience of loading on the factors, the means loadings were higher on the general factor (m = 0.62) than on the group factors (m = 0.39). The more‐traditional reliability estimates for the general and group factors were good: general factor, α = 0.83; omega total = 0.90; temper group factor, α = 0.80; omega total = 0.87; self‐harm group factor, α = 0.84; omega total = 0.86. However, the omega hierarchical coefficient was low for the group factors (temper, omega hierarchical = 0.15; self‐harm, omega hierarchical = 0.54) and was only acceptable for the general irritability factor (omega hierarchical = 0.75).

Discussion

Among a large European study of HD expansion carriers, we found that a bifactor interpretation is a structurally valid method of interpreting scores on the SIS, thus retaining the notion of an overall assessment of irritability, while recognizing the multidimensionality of the SIS. Two different considerations of the multidimensionality of the SIS were explored within the current study. The first was Snaith's original conceptualization of outward and inward irritability5 and the second was suggested by findings from an EFA of “temper” and “self‐harm” items. When these different conceptualizations of irritability were assessed further using CFA, we found that, regardless of whether the formulation comprised inward/outward dimensions or temper/self‐harm dimensions, the statistical solution suggested that an overall score was the most stable. Therefore, based on the current findings, the primary recommendation is that all SIS items are used to produce an overall measure of irritability.

These findings have relevance for the measurement and treatment of irritability in people with HD. A higher‐order bifactor model suggests the accommodation of both general factor and group factors of irritability, with our findings suggesting that an emphasis should be made on the former. This implies a change in the understanding of what scores on the SIS represent among people with HD. It may not be enough simply to see the SIS as measuring two separate factors (inward and outward) or a unidimensional construct. Rather, whereas it is possible to recognize multidimensional aspects of the SIS, scores on the SIS are also informed by a general SIS factor. This suggests that, alongside group factors, a general factor of irritability may need to be considered. For example, this might be hypothesized as neuropathological changes that occur in HD having an underlying influence on SIS scores. Recent support for this hypothesis was provided by the TRACK‐HD study that identified irritability to be associated with a distinct pattern of microstructural changes in the posterior tracts of the left hemisphere.29 The researchers suggested that irritability may arise in situations when someone with HD may be stretched cognitively and is consistent with another Track‐on study suggesting that left hemispheric deterioration appears to occur first in HD, with compensation by the right hemisphere as illustrated by functional MRI.46 Alternatively, generalized irritability may be underpinned by other changes endemic to the experience of chronic illness, such as cognitions that are activated in a range of contexts and might lead to different behavioral/emotional outcomes depending on a range of individual or situational factors inherent to that specific context.

These findings and suggestions have considerable significance, given that the study of irritability in HD, and other neurological disorders, is still in its infancy. The identification of inward and outward dimensions or temper and self‐harm aspects of irritability, within a general factor of irritability, may be important in further considerations of irritability using the SIS. For example, researchers may wish to examine how the different formulations of irritability are associated with clinical risk, especially in the context of other factors in HD that may contribute to complex clinical presentations (such as executive functioning difficulties of heightened impulsivity, poor risk assessment, and reduced problem‐solving strategies47, 48). The clinical risks that could be associated with such conceptualizations of irritability may include physical aggression, risk of harming self, or heightening risk of being harmed by other people (e.g., through losing one's temper easily with other people). Future research might wish to look at whether the aspects of irritability, as measured by the different formulations of the SIS, has any predictive utility regarding such risk behaviors among people with HD. Further consideration might be given to the various aspects of HD that potentially contribute to the general factor of irritability across the different stages of the disease. These range from biological contributions, such as white matter changes,29 to neuropsychological aspects, such as cognitive overload,29 to cognitive appraisals around having HD,30 to frustrations over reduced functional, motor and cognitive abilities, and changes in personal relationships.31

Despite these new findings, we also identify a number of potential limitations. The current REGISTRY sample may not be representative of the HD population as a whole. For instance, participants within this study who were in the more‐advanced stages of the disease may have been less likely to have engaged in the research. Also, the data were collected from a Europe‐wide sample involving translated versions of instruments. Therefore, in studying the data as a whole, we did not consider how expressions of irritability are construed differently cross‐culturally, which suggests caution in applying the general findings to any single European sample.

In summary, this article outlines the first factor analysis study of scores obtained from the SIS across a large European sample of an HD population. The study provides evidence for two bifactor models and suggests a change is needed in how we should conceptually consider irritability in terms of both general and group factors. Mindful that irritability may stem from a general factor, we recommend that the SIS is best used as a general measure of irritability among HD gene expansion carriers.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

J.M.: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A

M.D.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2C, 3a

M.U.: 1B, 2C, 3b

J.S.: 2C, 3b

JM REGISTRY site investigators of EHDN: 1C

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: J.M. has been employed by the University of Leicester and has received royalties from Pearson Education. M.D. has been employed by Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust. M.U. has been employed by Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust. J.S. has been employed by Lancaster University.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. REGISTRY investigators of the European Huntington's Disease Network, 2004–2014.

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

REGISTRY investigators are listed in Supporting Appendix 1.

References

- 1. Monastero R, Di Fiore P, Ventimiglia GD, Camarda R, Camarda C. The neuropsychiatric profile of Parkinson's disease subjects with and without mild cognitive impairment. J Neural Transm 2013;120:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Duijn E, Kingma EM, van der Mast RC. Psychopathology in verified Huntington's disease gene carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;19:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cox JH, Cavanna AE. Irritability symptoms in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;27:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hammond FM, Davis C, Cook JR, Philbrick P, Hirsch MA. A conceptual model of irritability following traumatic brain injury: a qualitative, participatory research study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2016;31:E1–E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Snaith RP, Constantopoulos AA, Jardine MY, McGuffin P. A clinical scale for the self‐assessment of irritability. Br J Psychiatry 1978;132:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Snaith RP, Taylor CM. Irritability: definition, assessment and associated factors. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Fiedorowicz JG. Overt irritability/anger in unipolar major depressive episodes: past and current characteristics and implications for long‐term course. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fava M, Hwang I, Rush AJ, Sampson N, Walters EE, Kessler RC. The importance of irritability as a symptom of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry 2010;15:856–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Julien L, Thompson C, Wild S, et al. Psychiatric disorders in preclinical Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:939–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Epping EA, Kim JI, Craufurd D, et al.; PREDICT‐HD Investigators and Coordinators of the Huntington Study Group . Longitudinal psychiatric symptoms in prodromal Huntington's disease: a decade of data. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Duijn E, Reedeker N, Giltay EJ, Eindhoven D, Roos RA, van der Mast RC. Course of irritability, depression and apathy in Huntington's disease in relation to motor symptoms during a two‐year follow‐up period. Neurodegener Dis 2014;13:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Duijn E, Craufurd D, Hubers AA, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in a European Huntington's disease cohort (REGISTRY). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:1411–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sprengelmeyer R, Orth M, Muller HP, et al. The neuroanatomy of subthreshold depressive symptoms in Huntington's disease: a combined diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and voxel‐based morphometry (VBM) study. Psychol Med 2014;44:1867–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tabrizi SJ, Reilmann R, Roos RA, et al. Potential endpoints for clinical trials in premanifest and early Huntington's disease in the TRACK‐HD study: analysis of 24 month observational data. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirkwood SC, Siemers E, Viken R, et al. Longitudinal personality changes among presymptomatic Huntington disease gene carriers. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2002;15:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rickards H, De Souza J, van Walsem M, et al. Factor analysis of behavioural symptoms in Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:411–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Callaghan J, Stopford C, Arran N, et al. Reliability and factor structure of the Short Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington's disease (PBA‐s) in the TRACK‐HD and REGISTRY studies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;27:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Craufurd D, Thompson JC, Snowden JS. Behavioral changes in Huntington disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001;14:219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kingma M, van Duijn E, Timman R, van CR, Roos AC. Behavioural problems in Huntington's disease using the Problem Behaviours Assessment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wheelock VL, Tempkin T, Marder K, et al. Predictors of nursing home placement in Huntington's disease. Neurology 2003;60:998–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams JK, Skirton H, Barnette J, Paulsen JS. Family caregiver personal concerns in Huntington disease. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maxted C, Simpson J, Weatherhead S. An exploration of the experience of Huntington's disease in family dyads: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Genet Couns 2014;23:339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hubers AA, van Duijn E, Roos R, et al. Suicidal ideation in a European Huntington's disease population. J Affect Disord 2013;151:248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huntington Study Group . United Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord 1996;11:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kloppel S, Stonnington M, Petrovic P, et al. Irritability in pre‐clinical Huntington's disease. Neuropsychologia 2010;48:549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vassos E, Panas M, Kladi A, Vassilopoulos D. Higher levels of extroverted hostility detected in gene carriers at risk for Huntington's disease. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:1347–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carlozzi NE, Miciura A, Migliore N, Dayalu P. Understanding the outcome measures used in Huntington disease pharmacological trials: a systematic review. J Huntingtons Dis 2014;3:233–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen FF, West SG, Sousa KH. A comparison of bifactor and second‐order models of quality of life. Multivar Behav Res 2006;41:189–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gregory S, Scahill RI, Seunarine KK, et al. Neuropsychiatry and white matter microstructure in Huntington's disease. J Huntingtons Dis 2015;4:239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arran N, Craufurd D, Simpson J. Illness perceptions, coping styles and psychological distress in adults with Huntington's disease. Psychol Health Med 2014;19:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dawson S, Kristjanson LJ, Toye CM, Flett P. Living with Huntington's disease: need for supportive care. Nurs Health Sci 2004;6:123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shoulson I, Fahn S. Huntington's disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology 1979;29:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gorsuch RL. Factor Analysis. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods 1999;4:272–299. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zwick WR, Velicer WF. Factors influencing five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychol Bull 1986;99:432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2nd ed New York: McGraw‐Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kline P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing. London: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barrett P. Structural equation modelling: adjudging model fit. Pers Individ Dif 2007;42:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness‐of‐fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 1980;88:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A Beginner's Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kloppel S, Gregory S, Scheller E, et al. Compensation in preclinical Huntington's disease: evidence from the Track‐On HD study. EBioMedicine 2015;2:1420–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hamilton JM, Salmon DP, Corey‐Bloom J, et al. Behavioural abnormalities contribute to functional decline in Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:120–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duff K, Paulsen JS, Beglinger LJ, et al. “Frontal” behaviors before the diagnosis of Huntington's disease and their relationship to markers of disease progression: evidence of early lack of awareness. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010;22:196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. REGISTRY investigators of the European Huntington's Disease Network, 2004–2014.