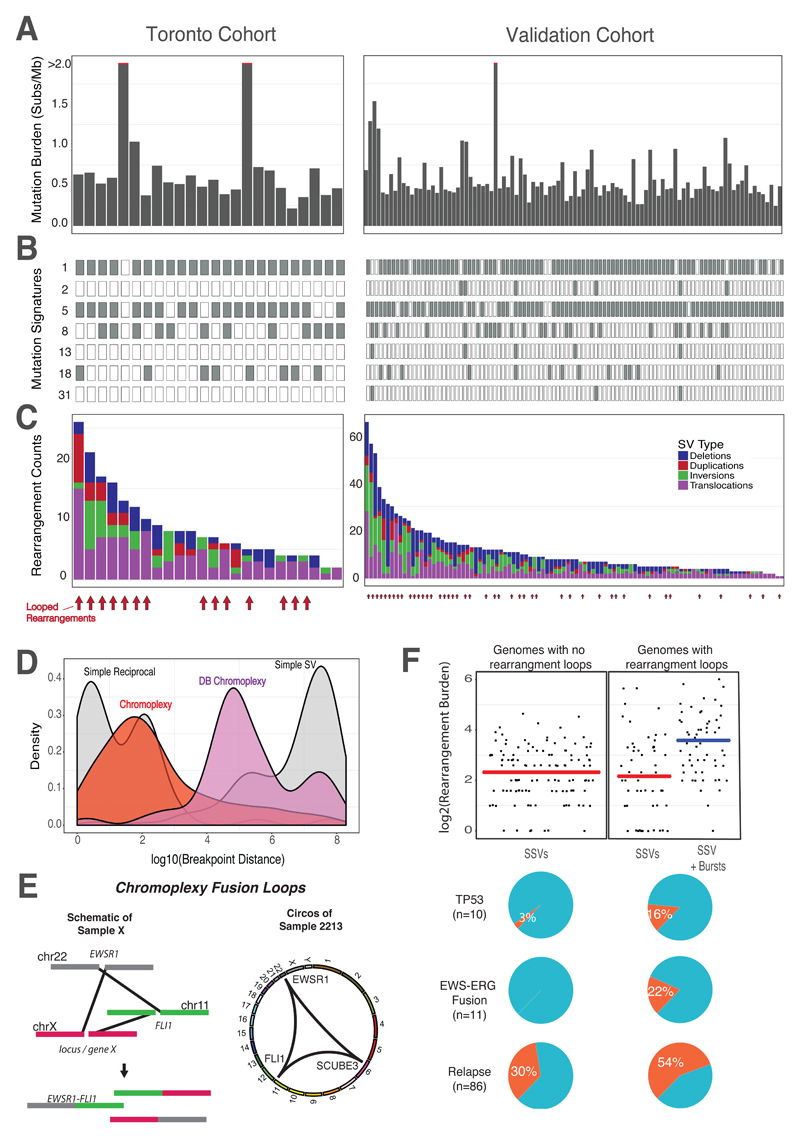

Fig. 1. Mutation Landscape of Ewing Sarcoma.

The initial cohort consisted of 50 primary ES tumors, of which, 23 underwent whole genome sequencing (Toronto cohort, left). One rearrangement screen sample (sample 4462) is included in this figure. The validation cohort consisted of 100 ES whole-genomes from Tirode et al. 2014 (right). (A) Somatic mutation burden for Ewing sarcoma. The mutation burden of all genome samples are shown. Three outlier samples with >2 mutations/MB, are indicated by the red line. (B) Ewing sarcoma mutation signatures. Mutation signature analysis, defined by the proportion of 96 possible trinucleotides, identified common mutation patterns in most samples (Age-associated, “clock-like” signature 1). Other signatures included #2, 5, 8, 13, 18, and 31. Signatures 2 and 13 are associated with the activity of the AID/APOBEC family of cytidine deaminase, while Signature 5 is also clock-like in some cancers, but not ES (11, 13). Signatures 8 and 18 have an unknown molecular aetiology, however it has been suggested that Signature 18 is caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS)(43). Signature 31 is believed to be the result of exposure to platinum-based antineoplastic therapy (24).(C) Rearrangement profiles for Ewing sarcoma. Shown are the burden of deletions (blue), duplications (red), inversions (green) and translocations (purple) in individual ES genomes. Samples with chained complex rearrangements (looped rearrangements) are highlighted by red arrows (14/24 for Toronto, 38/100 for Validation, aggregated prevalence: 52/124). (D) Rearrangement breakpoint clusters. The aggregated density distributions of the genomic distance between consecutive rearrangement breakpoints are shown. Reciprocal breakpoints are close together (~102 bp) because there is an equal exchange of genetic material arising from a single break on each chromosome. Chromoplectic rearrangements (red) overlap this range due to the proximity breakpoints involved in looped rearrangements. Deletion bridge (DB) chromoplexy (purple) are looped rearrangement clusters in which a deletion spans two breakpoints, resulting in breakpoint distances that are farther apart (illustrated in fig. S11). Non-complex breakpoints (simple structural variants) are far apart (~108 bp). (E) Schematic diagram of chromoplexy fusion loops. Illustrative example of chromoplexy in Ewing sarcoma shows three chromosomes undergoing double-strand breakage, shuffling and religation in an aberrant configuration. This phenomenon generates the canonical fusion, EWSR1-FLI1 (ERG or ETV1) and disrupts a third locus, X, in a one-off burst of rearrangements. In reality, up to 8 chromosomes may be disrupted in this looping pattern. A representative genome-wide Circos plots depicting genomic rearrangements in an Ewing sarcoma tumor (from the discovery cohort), which are organized in a loop. (F) Genomic correlates and clinical impact of looped rearrangements. In genomes without rearrangement loops, only simple structural variants (SSV) exist with an average rearrangement burden of 7 rearrangements/sample. This rate is similar to the background SSV rate (determined by removing rearrangements involved in a loop) in genomes with rearrangement bursts (compare the two red lines). The additional complexity of looped rearrangements results in higher genomic instability in these tumors. The most common genomic alterations include somatic TP53 mutations, which are rare, but enriched in patients with complex genomes (top pie chart, p < 0.05). EWS-ERG fusions are also rare, as they represent 10% of all Ewing sarcoma diagnoses, however all EWS-ERG fusion Ewing tumors are either chomothriptic or chromoplectic (middle pie chart). Lastly, patients with complex genomes tend to relapse (bottom pie chart, p < 0.05). All the markers of aggressive disease (high genomic instability, somatic TP53 and relapse) are present in tumors with complex genomes.