Abstract

East Coast fever (ECF) is a fatal sickness affecting cattle populations of eastern, central, and southern Africa. The disease is transmitted by the tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, and caused by the protozoan Theileria parva parva, which invades host lymphocytes and promotes their clonal expansion. Importantly, indigenous cattle show tolerance to infection in ECF-endemically stable areas. Here, the putative genetic bases underlying ECF-tolerance were investigated using molecular data and epidemiological information from 823 indigenous cattle from Uganda. Vector distribution and host infection risk were estimated over the study area and subsequently tested as triggers of local adaptation by means of landscape genomics analysis. We identified 41 and seven candidate adaptive loci for tick resistance and infection tolerance, respectively. Among the genes associated with the candidate adaptive loci are PRKG1 and SLA2. PRKG1 was already described as associated with tick resistance in indigenous South African cattle, due to its role into inflammatory response. SLA2 is part of the regulatory pathways involved into lymphocytes' proliferation. Additionally, local ancestry analysis suggested the zebuine origin of the genomic region candidate for tick resistance.

Keywords: local adaptation, landscape genomics, species distribution modelling, indigenous cattle, East Coast fever

Introduction

East Coast fever (ECF) is an endemic vector-borne disease affecting the species Bos taurus in eastern and central Africa. ECF etiological agent is the emo-parasite protozoan Theileria parva Theiler, 1904, vectored by the hard-bodied tick vector Rhipicephalus appendiculatus Neumann, 1901. The disease is reported to cause high morbidity and mortality in susceptible indigenous populations coming from outside endemic areas and among exotic breeds, thus undermining the livestock sector development in the affected countries (Norval et al., 1992; Olwoch et al., 2008; Muhanguzi et al., 2014).

Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer Sparrman, 1779) is T. parva native host, being its wild and asymptomatic reservoir (Oura et al., 2011). The primordial contact between buffalo-derived T. parva and domestic bovines probably occurred ~4500 years before present (YBP), following B. taurus migration into T. parva areal (Epstein, 1971). However, it is hard to define if the host jump affected taurine- or indicine-like B. taurus first, since no consensus can easily be reached to define who among the subspecies B. t. taurus and B. t. indicus was present in East Africa at that time (Freeman, 2006; Hiendleder et al., 2008; Decker et al., 2014; Magee et al., 2014; Mwai et al., 2015). In particular, African taurine migration might have occurred sometime between ~8,000 and 1,500 YBP (Magee et al., 2014; Mwai et al., 2015), and the most ancient zebuine colonization wave is estimated to have occurred between ~4,000 and 2,000 YBP from the Asian continent, as suggested by the first certain archaeological record dated 1,750 YBP (Freeman, 2006). Once T. parva spread to domestic populations, coevolution between the parasite and the new hosts likely led to the divergence between buffalo- (T. p. lawracei) and cattle-specific (T. p. parva) parasite strains (Hayashida et al., 2013; Sivakumar et al., 2014), and to the appearance of indigenous herds able to survive and recover from infection (Kabi et al., 2014; Bahbahani and Hanotte, 2015).

Most likely, such populations appeared (and still inhabit) areas where environmental conditions guaranteed the constant coexistence between vector, parasite, and domestic host. Such a combination, together with the evolution of some sort of resistance and/or tolerance (i.e., the capacity of reducing parasite burden or attenuating the symptoms caused by a given parasite burden, respectively), plausibly prompted the establishment of an epidemiological state referred to as endemic stability, a condition where hosts become parasite reservoirs while showing negligible clinical symptoms (Kivaria et al., 2004; Råberg et al., 2007; Gachohi et al., 2012; Laisser et al., 2017). However, to our knowledge no clear indication has been provided for a genetic control prompting survival and recovery from ECF (Bahbahani and Hanotte, 2015), although previous research identified the role of host genetics on both tolerance and resistance strategies in animals (Råberg et al., 2007), as in the case of B. taurus resistance to tropical theileriosis (Glass and Jensen, 2007; Chaussepied et al., 2010) and tick burden (Kim et al., 2017). Furthermore, the identification of adaptive variation responsible for survival to ECF would undoubtedly represent a sensible step forward toward sustainability and productivity of local agroecosystems.

Here, we explicitly test the hypothesis that indigenous host populations living in ECF-endemically stable areas are locally adapted to ECF burden, and investigate for selection signatures involved with ECF-tolerance/resistance. In particular, local adaptation is known to be promoted by spatially varying (i.e., divergent) natural selection (Kawecki and Ebert, 2004), leading a population at its native site to present higher fitness “than any other population introduced to that site” (Savolainen et al., 2013). Such conditions appear to be met in East Africa, where R. appendiculatus distribution is reported to be wide but patchy (implying a spatially heterogeneous ECF burden on local host populations; Olwoch et al., 2003, 2008), B. taurus presence is long-standing and its distribution wide (Robinson et al., 2014), and the introduction of allochthonous B. taurus populations into ECF-endemic areas proved unsuccessful, with mortality rates ranging 40–100% (Rubaire-Akiiki et al., 2006; Olwoch et al., 2008; Gachohi et al., 2012).

By testing for significant associations between environmental and genetic features of individuals (or populations) at their sampling sites, landscape genomics aims to detect the environmental drivers of divergent selection triggering adaptive variation (Rellstab et al., 2015). Here, we relied on a landscape genomics approach to search for signatures of local adaptation in the genomes of indigenous B. taurus populations from Uganda, where the concomitant occurrence of endemically stable areas in the South-West and in the East of the country (Kivaria et al., 2004; Rubaire-Akiiki et al., 2006), spatially varying selection due to regional climatic differences (Kabi et al., 2014), and host populations connected by high rates of gene flow (Kawecki and Ebert, 2004; Stucki et al., 2017) is likely to have promoted local adaptation to the disease even over short time scales, i.e., from thousands of years to few decades (Stockwell et al., 2003; Crispo et al., 2010; Fraser et al., 2011).

Since endemic areas are currently inhabited by indigenous B. t. indicus and the B. t. indicus x African B. t. taurus crosses sanga and zenga (Hanotte et al., 2002; Mwai et al., 2015), two main hypotheses can be associated with the origin of local adaptation to ECF: (i) at first adaptation appeared in local African B. t. taurus populations and was then introgressed into zebu and derived sanga and zenga crossbreds; alternatively, (ii) it appeared in B. t. indicus, and then either evolved independently in zebuine populations of eastern Africa, or was imported from the Indian continent, where similar selective pressures are recorded (Singh et al., 1993; Boulter and Hall, 1999).

To search for ECF-specific signatures of selection, we first modelled R. appendiculatus potential distribution and T. p. parva infection risk in Uganda to define the spatially varying selective pressure over the host genomes, and then used this information to search for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) potentially involved into local adaptation to ECF through genotype-environment association analysis. Subsequently, we annotated candidate genes, and studied the ancestral origin of the identified candidate genomic regions by means of local ancestry analysis to shed light on the possible evolutionary origins of local adaptation.

Materials and methods

Ecological modelling

R. appendiculatus occurrence probability (ψR) and T. p. parva infection risk in cattle (γ) were modelled and used as environmental predictors into landscape genomics models. Geographical variability in both ψR and γ was assumed to describe the spatially heterogeneous selective pressure on cattle genomes. Further, S. caffer occurrence probability (ψS) was estimated and used in combination with ψR to model γ, as the geographical proximity between Cape buffaloes and cattle herds constitutes a factor for explaining ECF incidence. The following three sections will describe data and methods used to estimate ψR, ψS, and γ.

Raster data

Bioclimatic variables (BIO) referring to the time span between 1960 and 1990 were collected from the WorldClim database (v.1.4. release3) (Hijmans et al., 2005) at a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds and in the un-projected latitude/longitude coordinate reference system (WGS84 datum). Altitude information was collected from the SRTM 90 m Digital Elevation Database (v.4.1) (Jarvis et al., 2008), which provides tiles covering Earth's land surface in the WGS84 datum, at 90 m resolution at the equator. Altitude was used to compute terrain slope through the function terrain implemented in the R package raster (Hijmans, 2016). The 10-year (2001–2010) averaged Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was derived for 72 ten-day annual periods from the “eMODIS products” (Supplementary Text 1) (US Geological Survey1), in the WGS84 datum, and at a resolution of 250 m at the equator. A raster file describing cattle density (number of animals/km2) was acquired from the Livestock Geo-Wiki database (Robinson et al., 2014), in the WGS84 datum, at a resolution of 1 km2 at the equator. A raster file describing each pixel distance from the nearest water source was obtained with the function distance within the R package raster. The “Land and Water Area” dataset from the Gridded Population of the World collection (GPV v.4) (CIESIN, 2016) was used to define water bodies in Uganda at a resolution of 30 arc-seconds with WGS84 datum.

All raster files were transposed into Africa Albers Equal Area Conic projection to guarantee a constant pixel size and meet the main assumption of the statistical technique used to model ψR and ψS, i.e., that each pixel presents the same probability to be randomly sampled in order to detect the species occurrence (Merow and Silander, 2014). Raster files were standardised to the same resolution (~0.85 km2), origin, and extent. To avoid the inclusion of potentially misleading background locations while characterizing the occurrence probability of terrestrial species, inland water surfaces were masked prior to ψR and ψS estimation (Barve et al., 2011). Quantum GIS (v.2.16.2) (QGIS Development Team, 2016) and the R package raster were used for raster files manipulation.

Species distribution models

The R package Maxlike (Royle et al., 2012) was used to model ψR and ψS over Uganda. Maxlike is able to estimate species occurrence probability (ψ) from presence-only data, by maximizing the likelihood of occurrences under the logit-linear model (Merow and Silander, 2014):

where ψx denotes the species occurrence probability in the x pixel of the landscape, β0 the model intercept (i.e., the expected prevalence across the study area), β the vector of slope parameters, and z(x) the vector of environmental variables for x. Occurrence probability in x is derived from the inverse logit:

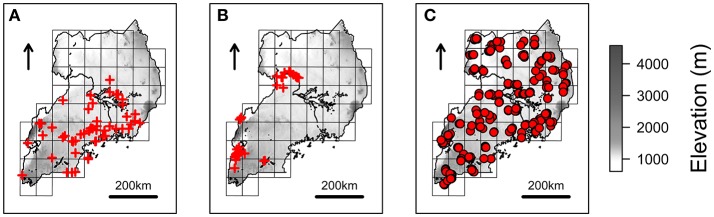

Fifty-one and 61 spatial records of R. appendiculatus and S. caffer (Figures 1A,B) were obtained from a tick occurrence database previously collected (Cumming, 1999b), and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, 2012), respectively.

Figure 1.

Species occurrences and NextGen sampling scheme. Red crosses represents the spatial records used to estimate Rhipicephalus appendiculatus (A) and Syncerus caffer (B) distributions over Uganda, as derived from Cumming (1999b) and GBIF (2012), respectively. Farms where cattle have been sampled to be genotyped and tested for Theileria parva parva infection are represented with red circles (C). The grid scheme used to sample farms during the NextGen project is shown on the background of each map (see main text), together with elevation.

The most relevant environmental variables affecting tick and Cape buffalo distributions were identified from the literature. Specifically, the BIO variables representing temperature/precipitation interaction in the most extreme periods of the year were used to model R. appendiculatus occurrence (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) (Cumming, 1999a, 2002), while altitude, terrain slope, NDVI, distance to water sources (Wd), and annual precipitation (BIO12) were used to model the Cape buffalo distribution (Pettorelli et al., 2011; Matawa et al., 2012; Naidoo et al., 2012). A Maxlike regression analysis was applied to individuate the NDVI values best predicting the available S. caffer occurrences, and the period April 6–15 was retained for subsequent analyses (Supplementary Figure 2). No variable depicting the top-down regulatory effect of predators on buffalo populations was considered, as bottom-up ecological mechanisms (like quantity and quality of food resources) are argued to play the main role in determining large herbivores distribution (Winnie et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Predictors used to model Rhipicephalus appendiculatus distribution.

| Bioclim variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| BIO8 | Mean temperature a of the wettest 3 months (quarter) of the year |

| BIO9 | Mean temperature of the driest quarter |

| BIO10 | Mean temperature of the warmest quarter |

| BIO11 | Mean temperature of the coldest quarter |

| BIO16 | Precipitationb of the wettest quarter |

| BIO17 | Precipitation of the driest quarter |

| BIO18 | Precipitation of the warmest quarter |

| BIO19 | Precipitation of the coldest quarter |

Temperature was transformed from dC° to C° prior analyses.

Precipitation is expressed in millimetres.

Collinearity was checked prior to analyses by computing pairwise absolute correlations (|r|) between variables, which were considered collinear when |r| exceeded the suggested threshold of 0.7 (Dormann et al., 2013). High collinearity was found among BIO variables, which were then subjected to principal components analysis (PCA) to obtain orthogonal predictors for ψR.

Obtained components were tested into univariate and multivariate R. appendiculatus distribution models. Particularly, components explaining up to 95% of the original variance (Jolliffe, 2002) were individuated and tested with different combinations into multivariate models, leading to a total of 12 candidate R. appendiculatus distribution models. Conversely, all the combinations of environmental variables were tested into univariate up to penta-variate Cape buffalo distribution models, resulting in a total of 31 candidate models for predicting S. caffer potential distribution.

In both cases, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used to select the best models (Aho et al., 2014). Bring's standardization (Bring, 1994; Cade, 2015) was applied on predictors before parameters' estimate, and the delta method was implemented to compute the 95% confidence intervals around the fitted ψRx and ψSx.

Infection risk model

In the context of the European Project NextGen2, 587 blood samples from Ugandan indigenous B. taurus were tested for the presence/absence of T. p. parva p104 antigen DNA sequence (Kabi et al., 2014). Samples were collected and georeferenced in correspondence of 203 farms distributed over a grid of 51 cells covering the whole Uganda, with an average of 12 (±4 s.d.) animals/cell, and three (±1 s.d.) animals/farm (Figure 1C).

ECF epidemiology is complex and determined by both biotic and abiotic factors (Norval et al., 1992). Particularly, R. appendiculatus occurrence (ψR) (Magona et al., 2008, 2011; Gachohi et al., 2011; Muhanguzi et al., 2014), cattle density (Cd) (Billiouw et al., 2002; Olwoch et al., 2008), potential proximity with S. caffer (ψS) and the maximal temperature in the warmest month of the year (BIO5) were considered to predict γ. BIO5 was used to account for the possible limiting effect of high temperatures on the parasite development into the tick (Young and Leitch, 1981). Predictors' values were obtained at the geographical position of each animal (i.e., at farm locations), checked for the presence of collinearity (as done for the species distribution models) and outliers (Supplementary Figure 3), and subsequently standardized following Bring's procedure prior to parameters' estimation.

Infection risk for any i-th animal was modelled using a binary mixed-effects logistic regression, where ψR, BIO5, Cd, and ψS were specified as fixed effects, and random intercepts were estimated for each farm to account for the possible influence of local environmental conditions and management practices (e.g., differential use of acaricides), as well as unmeasured biological features (e.g., breed- or individual-specific response to tick burden) (Gachohi et al., 2012). Since geographical position of samples was recorded at the farm-level, all the animals coming from a given farm were characterized by equal environmental values. Thus, the model can be written as:

where γij represents T. p. parva infection risk for the i-th animal in the j-th farm, β0 is the population intercept (Zuur et al., 2009), β0+b0j is the j-th farm random intercept, β the vector of slope parameters, and z(j) the vector containing the predictors' values as derived from the pixel where the j-th farm is located, equal for all the animals in j. In this way, animals in j are expected with the same predicted γ, so that infection risk in the j-th farm can be calculated using the population model from the previous equation:

Estimates of the parameters were obtained through the Maximum Likelihood criterion using the glmer function included in the R package lme4 (Bates et al., 2015).

Landscape genomics

Molecular datasets

The NextGen project genotyped 813 georeferenced indigenous B. taurus from Uganda using the medium-density BovineSNP50 BeadChip (54,596 SNPs; Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Landscape genomics analyses were carried out on this set of animals, which will be referred to as the “landscape genomics dataset” (LGD). Samples were collected according to the spatial scheme represented in Figure 1C, and encompassed 503 of the individuals tested for T. p. parva infection. Quality control (QC) procedures were carried out with the software Plink v.1.7 (Purcell et al., 2007). LGD was limited to autosomal chromosomes and pruned for minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01, genotype call rates <0.95, and individual call rate <0.9. Pairwise genome-wide identity-by-descent (IBD) values were estimated, and one individual per pair showing IBD>0.5 was excluded from analyses to reduce the risk of spurious associations due to unreported kinship (Turner et al., 2011). To avoid excluding too many individuals from nearby areas, spatial positions of the highlighted pairs were considered prior to removal.

Population genetic structure of Ugandan cattle was studied on the landscape genomics dataset merged with molecular data from other European taurine, African taurine, zebuine, and sanga populations retrieved from various sources and for different geographical areas worldwide (Supplementary Table 1). This extended dataset will be referred to as the “population structure dataset” (PSD). Plink was used to prune PSD for linkage disequilibrium (LD) >0.1 with sliding windows of 50 SNPs and step size of 10 SNPs (option –indep-pairwise 50 10 0.1), and to filter for the QC thresholds previously reported.

Population structure analysis

PSD was analysed with admixture v.1.3.0 (Alexander et al., 2009) for a dual purpose. Firstly, to provide genotype-environment association tests with population structure predictors in order to reduce the risk of false positive detections (Schoville et al., 2012; Rellstab et al., 2015). To this aim, we decided to use membership coefficients for the four-cluster solution (K=4), as this was reported to be the best partition based on the admixture cross-validation index for the same set of Ugandan individuals undergoing landscape genomics in the present study (Stucki et al., 2017). Due to strong collinearity (|r|>0.7) (Dormann et al., 2013) among the membership coefficients of two ancestral components, a PCA was performed trough the R function prcomp to obtain synthetic and orthogonal population structure predictors. Secondly, to identify the main gene pools present in Uganda in the context of a worldwide-extended dataset, and therefore guide selection of proper reference populations for local ancestry analysis.

Genotype-environment associations

We used the software samβada v.0.5.3 (Joost et al., 2007; Stucki et al., 2017) to test for associations between B. taurus genotypes and ψR and γ at sampling locations. Given diploid species and biallelic markers, samβada runs three models per locus, one for each possible genotype. Each model estimates the probability πi for the i-th individual to carry a given genotype, as a function of the considered environmental and population structure variables:

and thus:

Genotype-environment association tests were carried out through a likelihood-ratio test comparing a null and an alternative model for each genotype (Stucki et al., 2017). Particularly, null models comprised the population structure predictors alone, while alternative ones included population structure predictors plus either ψR or γ. A genotype was considered significantly associated with ψR and/or γ if the resulting p-value associated with the likelihood-ratio test statistic (D) was lower than the nominal significance threshold of 0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction for multiple testing (H0: D=0, αBH=0.05; Supplementary Texts 2–3). The R function p.adjust was used to perform p-values corrections, and predictors were centred prior to analysis to ease estimation of model parameters.

Gene annotation

Global linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay was estimated using snep v.1.11 (Barbato et al., 2015) to define LD extent around marker loci. A window of ±25 kbp (r2≈0.2) was then selected around those SNPs associated with ψR and/or γ to annotate genes in the Ensembl database release 87 (Aken et al., 2016). Annotated genes were investigated for known biological function according to the literature, and candidate genes identified based on their pertinence with ECF local adaptation.

Local ancestry

Molecular dataset

Target population for local ancestry analysis comprised 102 indigenous Ugandan B. taurus individuals collected during the NextGen sampling campaign (two animals sampled per cell; Figure 1C), and genotyped with the BovineHD BeadChip (777,961 SNPs; Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Reference populations (see Results section) were selected in coherence with the major Ugandan gene pools identified by the Admixture analysis (Supplementary Text 4). Target and reference populations were pooled in a “local ancestry dataset” (LAD). Only autosomal SNPs passing the same filtering parameters applied to LGD were retained for analysis.

PCAdmix analysis

Local ancestry investigation allows to assign the ancestral origin of a chromosomal region (window) given two or more reference populations, and have been used to infer the admixture history of closely related groups (Pasaniuc et al., 2009), identify signals of adaptive introgression (Barbato et al., 2017), and highlight target regions of recent selection (Tang et al., 2007). Here, PCAdmix v.1.0 (Brisbin et al., 2012) was used to infer local genomic ancestry of the Ugandan samples. Given the SNPs density present in LAD (i.e., one SNP every ~3.4 kbp, on average), we used 20 SNPs per window to obtain a window size comparable to the optimal one suggested in Brisbin et al. (2012).

Beta regression analysis

Genomic windows hosting SNPs in linkage with the candidate genes for local adaptation were identified and their ancestry proportions computed per sampling cell (Figure 1C). Average ψR and γ per cell values (hereafter ψRc and γc, respectively) were derived using the zonal.stats function included in the R package spatialEco (Evans, 2017). In order to test for significant associations between ancestry proportions and ψRc and γc, a beta regression analysis was performed using the R package betareg (Cribari-Neto and Zeileis, 2010), according to the model:

where ai is the ancestry proportion observed in cell i, which is assumed to derive from a beta distribution B(μi, ϕ) with mean μi=E(ai) and precision parameter ϕ, xi is either average ψR or γ in cell i, β0 and β1 are intercept and regression coefficient, respectively. Expected ancestry proportion in i was calculated through the inverse logit:

Ancestry proportions were transformed prior to analysis (Smithson and Verkuilen, 2006), and the Maximum Likelihood criterion was used to estimate model parameters.

Ethics statement

The NextGen sampling campaign was carried out during years 2011 and 2012, before Directive 2010/63/EU came into force (i.e., 1 January 2013). Thus, all experimental procedures were compliant with the former EU Directive 86/609/EEC, according to which no approval from dedicated animal welfare/ethics committee was needed for this study. The permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) reference number NS 325 (Kabi et al., 2014). The permission to carry out the sampling at each farm was obtained directly from the owners.

Results

Ecological modelling

Species distribution models

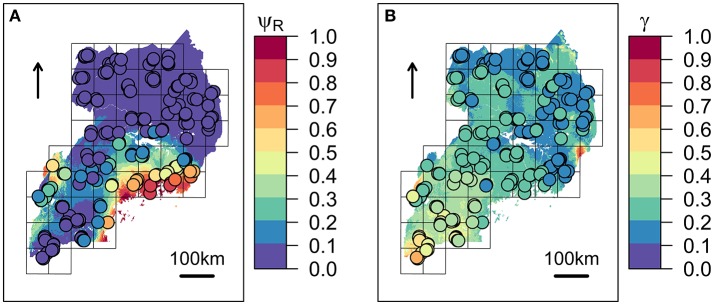

The first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) accounted for more than 95% of the variance among the BIO predictors, and were subsequently tested into multivariate Maxlike models to estimate ψR. Particularly, PC1 (61%) was mainly correlated with BIO variables linked to temperature (BIO8, BIO9, BIO10, and BIO11), PC2 (19%) with precipitation (BIO16, BIO17, BIO18, and BIO19), and PC3 (15%) with both temperature and precipitation (BIO19 and BIO8) (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 5). The model employing PC1, PC2, and PC3 was selected based on the BIC metric (Supplementary Figure 6), with PC1, and PC2 showing a significant positive effect on the tick distribution, and PC3 a significant negative effect (Table 2) (H0: βi=0, α=0.05). The model predicts low habitat suitability in the regions North of the Lakes Kwania, Kyoga and Kojwere (0<ψR<0.1), and favourable ecological conditions around Lake Victoria (0.4<ψR<1) and South-West of Lake Albert (0.4<ψR<0.8), these latter separated by a corridor of lower suitability (0<ψR<0.3) (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 7).

Table 2.

Maxlike results for Rhipicephalus appendiculatus distribution model.

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | p-value | ORa | ORlowb | ORupc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | −2.905 | 0.561 | 2.24E−07*** | 0.055 | 0.018 | 0.164 |

| PC1 | 0.796 | 0.303 | 8.56E−03** | 2.217 | 1.224 | 4.014 |

| PC2 | 0.822 | 0.37 | 2.62E−02* | 2.275 | 1.102 | 4.698 |

| PC3 | −1.799 | 0.629 | 4.27E−03** | 0.165 | 0.048 | 0.568 |

Point estimates (Estimate) of the standardized regression coefficients (Coefficient) are reported on the logit scale together with their standard errors (SE), p-values and the associated odds ratios (OR). A significant effect is reported with

when the p-value (p) associated to a regression coefficient is ≤ 0.001;

when 0.001 < p < 0.01;

when 0.01 < p < 0.05.

Odds ratios associated with regression coefficients express the expected change in the ratio ψR/(1–ψR), for a one standard deviation increase of the concerned predictor, holding all the other predictors fixed at a constant value.

Odds ratio 95% confidence interval (CI), lower bound.

Odds ratio 95% CI, upper bound.

Figure 2.

Predicted spatial distributions for ECF vector and infection risk in cattle. (A) Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability (ψR) as predicted by the selected distribution model. (B) Predicted Theileria parva parva infection risk (γ). Colour from blue to red tones corresponds to increasing values of ψR and γ. Sampled farms are represented with circles, and coloured according to ψR and γ values estimated at their geographical location.

No excessive collinearity was recorded among the predictors for ψS. The best model according to the BIC metric included: altitude, annual precipitation, average NDVI, and distance from the nearest water source (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 8). The model predicts the highest habitat suitability (0.2<ψS<0.8) in the near proximity of the water bodies (especially along the White Nile in the North-West, the south-eastern coasts of Lake Édouard, and the northern coasts of Lake George), and in small areas near the Katonga Game Reserve (Supplementary Figure 9).

Table 3.

Maxlike results for Syncerus caffer distribution model.

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | p-value | ORa | ORlowb | ORupc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | −9.130 | 0.790 | 6.46E−31*** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Altitude | −1.095 | 0.293 | 1.90E−04*** | 0.335 | 0.188 | 0.594 |

| BIO12 | −0.800 | 0.180 | 9.03E−06*** | 0.449 | 0.316 | 0.639 |

| NDVI | 2.862 | 0.329 | 3.38E−18*** | 17.499 | 9.181 | 33.343 |

| Wd | −1.996 | 0.434 | 4.23E−06*** | 0.136 | 0.058 | 0.318 |

Point estimates (Estimate) of the standardized regression coefficients (Coefficient) are reported on the logit scale together with their standard errors (SE), p-values and the associated odds ratios (OR). Significant regression coefficients are highlighted with

when their p-values (p) are ≤ 0.001; **when 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; *when 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05.

Odds ratios associated with regression coefficients express the expected change in the ratio ψS/(1–ψS), for a one standard deviation increase of the concerned predictor, holding all the other predictors fixed at a constant value.

Odds ratio 95% confidence interval (CI), lower bound.

Odds ratio 95% CI, upper bound.

Infection risk model

Following outliers inspection, ψR, Cd, and ψS were transformed on the log10 scale to reduce the observed skewness in the distributions (Supplementary Figure 3). No excessive collinearity was observed among the model predictors (|r|<0.7). All the explanatory variables except for Cd showed a significant effect (H0: βi=0, α=0.05) on infection risk. Particularly, BIO5 and ψR showed a negative association with γ, while ψS resulted positively associated (Table 4). Overall, northern regions of Uganda present a low probability of infection (0.1<γ<0.3). A similar range is observed southwards, in the region comprised between Lake Kyoga, Lake Victoria, Lake Albert and the eastern borders with Kenya. South-westwards, infection probability increases following a positive gradient from γ≈0.30 to γ≈0.70 in the most southern districts (Figure 2B).

Table 4.

Infection risk model results.

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | p-value | ORa | ORlowb | ORupc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | −1.128 | 0.115 | 1.21E−22*** | 0.324 | 0.258 | 0.406 |

| log10(ψR) | −0.219 | 0.105 | 3.72E−02* | 0.803 | 0.654 | 0.987 |

| BIO5 | −0.432 | 0.104 | 3.18E−05*** | 0.649 | 0.529 | 0.796 |

| log10(Cd) | 0.015 | 0.105 | 8.86E−01 | 1.015 | 0.826 | 1.247 |

| log10(ψS) | 0.246 | 0.111 | 2.67E−02* | 1.279 | 1.029 | 1.590 |

Point estimates (Estimate) of the standardized regression coefficients (Coefficient) are reported on the logit scale together with their standard errors (SE), p-values and the associated odds ratios (OR). Significant regression coefficients are highlighted with

when their p-values (p) are ≤ 0.001; **when 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01;

when 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05.

Odds ratios associated with regression coefficients express the expected change in the ratio γ/(1–γ), for a one standard deviation increase of the concerned predictor, holding all the other predictors fixed at a constant value.

Odds ratio 95% confidence interval (CI), lower bound.

Odds ratio 95% CI, upper bound.dPopulation intercept.

Landscape genomics

Population structure analysis

After pruning for MAF, LD, genotype and individual call rates, PSD counted 12,925 SNPs and 1,355 individuals, among which 743 from Uganda, 131 European taurine, 158 African taurine, 195 sanga from outside Uganda, and 128 zebu cattle.

Sanga and zebuine ancestries were the most represented in Uganda. Particularly, on average the sanga component constituted 76% (±13%) of the individual ancestries, whereas the zebuine counted 18% (±13%), with more than half of the individuals showing a zebuine proportion >20%. Further, ~3% of African and European taurine genomic ancestry components was also observed (Supplementary Figure 4). Genomic components showed spatial structure, the zebuine gene pool being more present in the North-East of the country, and the sanga in central and south-western Uganda (Supplementary Figure 10) (Stucki et al., 2017). The African taurine ancestry component was detectable as background signal especially in the North-West and South-West, whereas European introgression was mostly observed in the South-West.

The first three principal components (PC1, PC2 and PC3, respectively) explained almost the totality of the variance within admixture Q-scores for K=4; PC1 split the dataset between sanga and zebu gene pools, and PC2 and PC3 identified the European and African taurine components, respectively. Thus, these three PCs were used as population structure predictors to account for population structure within LGD in the landscape genomics models.

Genotype-environment associations

After QC, LGD counted 40,886 markers and 743 animals (the same in PSD) from 199 farms (4 ± 1 samples/farm), over 51 cells (15 ± 5 samples/cell).

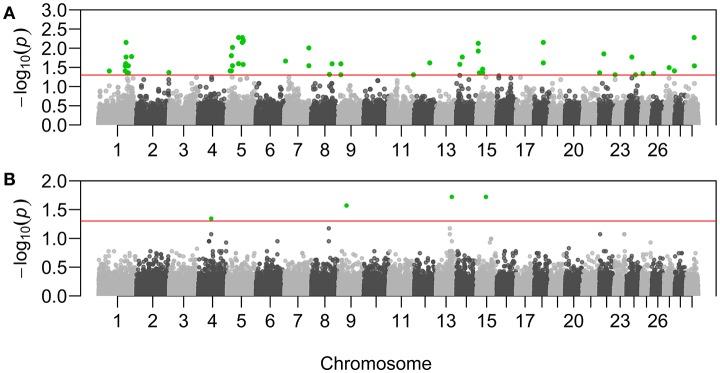

Sixty-three genotypes across 41 putative adaptive loci resulted significantly associated with ψR (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 2, and Supplementary Figures 11–12). Eight genotypes across seven loci resulted significantly associated with γ (Figure 3B, Supplementary Table 3, and Supplementary Figures 11–12).

Figure 3.

Manhattan plots of the genotype-environment associations. X-axis reports chromosomal position of the tested SNPs on B. taurus chromosomes. Y-axis reports the test statistic p-values (p) for the associations with Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability (A), and with Theileria parva parva infection risk (B). P-values are displayed for each genotype after the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction, and on the –log10 scale. Nominal significance threshold (αBH=0.05) is displayed as a red line, and significant p-values are highlighted in green.

Gene annotation

Among the 41 loci significantly associated with ψR, 18 presented at least one annotated gene in the Ensembl database in close proximity (Table 5A and Supplementary Figure 12). Locus BTA-113604-no-rs (hereafter BTA-113604) is located ~12.5 kbp apart from the Protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, type I (PRKG1) gene on chromosome 26. PRKG1 was already proposed as a candidate gene for tick resistance in South African Nguni cattle (Mapholi et al., 2016).

Table 5.

Gene annotation for the loci significantly associated with ψR (A) and γ (B).

| SNP ID | Genotype(s) | Chr. | Position | Annotated gene | Biological function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-110339 | AA,AC | 1 | 111,495,891 | Uncharacterized (111,445,583–111,512,320) | - |

| Hapmap34409-BES7_Contig244_858 | AA | 1 | 120,149,924 | Glycogenin-1 (GYG1; 120,090,467–120,127,892) | Energy metabolism and angiogenesis (Lancaster et al., 2014) |

| Hapmap34056-BES2_Contig421_810 | AG,GG | 1 | 138,178,130 | DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C13 (DNAJC13; 138,139,496–138,305,752) | Heat shock proteins (Kodiha et al., 2012) |

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-32909 | CC,AC | 5 | 67,846,632 | 5′-nucleotidase domain containing 3 (NT5DC3; 67,791,379–67,850,986) | UP-regulated genes for iron content in Nelore cattle (Wellison Jarles da Silva, 2015) |

| Uncharacterized (67,852,917–67,930,472) | – | ||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-37845 | AG,AA | 5 | 48,633,731 | Methionine sulfoxide reductase B3 (MSRB3; 48,563,806–48,743,354) | Affect ear floppiness and morphology in dogs (Boyko et al., 2010) |

| BTA-46975-no-rs | CG,GG | 5 | 68,220,538 | Thioredoxin reductase 1. cytoplasmic (TXNRD1; 68,239,611–68,302,678) | Milk production and oocyte developmental competence in cattle (Gilbert et al., 2012; Ghorbani et al., 2015) |

| Hapmap51626-BTA-73514 | AA,AG | 5 | 48,834,486 | Inner nuclear membrane protein Man1 (LEMD3; 48,773,272–48,844,474) | Height in pigs and cattle (Frantz et al., 2015) |

| UA-IFASA-6140 | AG,AA | 7 | 102,472,846 | ST8 alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminide alpha-2.8-sialyltransferase 4 (ST8SIA4; 102,456,175–102,555,855) | Metabolism of milk glycoconjugates in mammals (Song et al., 2016) |

| BTB-00292673 | AA | 7 | 4,953,801 | Phosphodiesterase 4C (PDE4C; 4,927,816–4,939,026) | Fertility (Glick et al., 2011) |

| Member RAS oncogene family (RAB3A; 4,944,325–4,950,010) | Calcium exocytosis in neurons (Brondyk et al., 1995) | ||||

| MPV17 mitochondrial inner membrane protein like 2 (MPV17L2; 4,950,069–4,953,210) | Immune system (Brütting et al., 2016) | ||||

| Hapmap31116-BTA-143121 | AA | 8 | 75,973,285 | Epoxide hydrolase 2 (EPHX2; 75,908,165–75,977,482) | In vitro maturation. fertilization and culture on bovine embryos (Smith et al., 2009) |

| L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO; 75,984,696–76,010,699) | Involved into vitamin C production in pigs (Hasan et al., 2004) | ||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-104610 | AG | 11 | 104,293,559 | Surfeit 6 (SURF6; 104,296,135–104,302,894) | Housekeeping gene (Magoulas et al., 1998) |

| Mediator complex subunit 22 (MED22; 104,305,076–104,311,650) | Gestation length in Nelore cattle (Matos et al., 2013) | ||||

| Ribosomal protein L7a (RPL7A; 104,311,808–104,315,125) | Oocyte developmental competence in cattle (Gilbert et al., 2012) | ||||

| Uncharacterized (104,315,458–104,334,584) | - | ||||

| Small nucleolar RNA (SNORD24; 104,312,993–104,313,063) | May act as methylation guide for RNA targets (Kiss-László et al., 1996) | ||||

| Small nucleolar RNA (SNORD36; 104,314,558–104,314,622) | 2'-O-ribose methylation guide (Galardi et al., 2002) | ||||

| Small nucleolar RNA (snR47; 104,313,768–104,313,828) | 2'-O-methylation of large and small subunit rRNA (Samarsky and Fournier, 1999) | ||||

| Small nucleolar RNA (SNORD24; 104,312,260–104,312,334) | As above | ||||

| Small nucleolar RNA (SNORD36; 104,314,159–104,314,231) | As above | ||||

| BTB-00839408 | AG. AA | 22 | 18,978,658 | Metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 precursor (GRM7; 18,740,484–19,647,747) | Might be related to parasite resistance (Xu et al., 2016) |

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-39898 | GG | 22 | 1,319,636 | Novel gene (1,310,943–1,311,505) | – |

| ARS-BFGL-BAC-31319 | AA | 23 | 4,847,028 | 3-hydroxymethyl-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase like 1 (HMGCLL1; 4,7 09,297–4,906,605) | Involved into ketogenesis (Tetens et al., 2015) |

| Hapmap51155-BTA-11643 | AA | 24 | 38,086,180 | DLG associated protein 1 (DLGAP1; 37,994,546–38,293,883) | Role in neurological development and behavioral disorders (Sorbolini et al., 2015) |

| Hapmap57868-rs29020458 | AA | 24 | 22,746,291 | Dystrobrevin alpha (DTNA; 22,445,691–22,767,026) | Formation and stability of synapses (Sjö et al., 2005) |

| U6 spliceosomal RNA (U6; 22,759,777–22,759,879) | Participate into spliceosome formation (Marz et al., 2008) | ||||

| BTA-113604-no-rs | AA | 26 | 8,356,096 | Protein kinase. cGMP-dependent. type I (PRKG1; 6,906,081–8,343,629) | Tick resistance in South African Nguni cattle (Mapholi et al., 2016) |

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-18933 | GG | 29 | 34,650,967 | Opioid binding protein/cell adhesion molecule like (OPCML; 34,554,780–35,085,038) | Role in opioid receptor function in humans (Smith et al., 1993) |

| B | |||||

| BTB-01298953 | AA | 4 | 54,930,726 | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3A (PPP1R3A; 54,866,421–54,906,096) | Glycogen synthesis in humans and mice (Savage et al., 2008) |

| BTA-33234-no-rs | GG | 13 | 66,291,997 | DLG associated protein 4 (DLGAP4; 66,204,671–66,292,988) | Neuronal membrane protein (Takeuchi et al., 1997) |

| Myosin light chain 9 (MYL9; 66,306,260–66,314,230) | May participate in regulation of muscle contraction (Kumar et al., 1989) | ||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-112656 | AA | 13 | 66,336,246 | Myosin light chain 9 (MYL9; 66,306,260–66,314,230) | As above |

| TGFB induced factor homeobox 2 (TGIF2; 66,334,680–66,351,481) | Transcriptional repressor (Imoto et al., 2000) | ||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-110102 | GG | 13 | 66,370,867 | TGFB induced factor homeobox 2 (TGIF2; 66,334,680–66,351,481) | As above |

| TGIF2-C20orf24 readthrough (C13H20orf24 alias RIP5; 66,362,562–66,369,978) | May promote apoptosis in humans (Zha et al., 2004) | ||||

| Src-like-adaptor 2 (SLA2; 66,368,694–66,395,549) | Downregulation of T and B cell-mediated responses (Holland et al., 2001) | ||||

| ARS-BFGL-NGS-24867 | AA | 13 | 66,395,465 | Src-like-adaptor 2 (SLA2; 66,368,694–66,395,549) | As above |

| NDRG family member 3 (NDRG3; 66,398,147–66,594,149) | Linked to prostate cancer cells growth (Lee et al., 2016) | ||||

| Hapmap39482-BTA-36746 | CC,AC | 15 | 40,279,014 | TEA domain transcription factor 1 (TEAD1; 40,303,805–40,482,346) | Transcription, factor promoting apoptosis in mammals (Landin Malt et al., 2012) |

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with genes annotated in the Ensembl database are reported with the genotype(s) originally highlighted by SAMHβADA, the membership chromosome (Chr) and physical position in base pairs on the chromosome, as well as the names and biological function of the annotated genes, as found for a reference species. Physical position of the annotated genes is reported in brackets after the gene names (fifth column).

Six out of the seven loci significantly associated with γ presented at least one annotated gene within the selected window size (Table 5B and Supplementary Figure 12). Two SNPs (ARS-BFGL-NGS-110102 and ARS-BFGL-NGS-24867, hereafter ARS-110102 and ARS-24867, respectively) were proximal to the Src-like-adaptor 2 (SLA2) gene on chromosome 13. SLA2 human orthologue encodes the Src-like-adaptor 2, a member of the SLAP protein family which regulates the T and B cell-mediated immune response (Holland et al., 2001). Given T. p. parva known ability to promote the proliferation of T and B cells (Baldwin et al., 1988; Dobbelaere and Küenzi, 2004), we considered SLA2 as a second candidate gene for ECF local adaptation.

Local ancestry

PCAdmix analysis

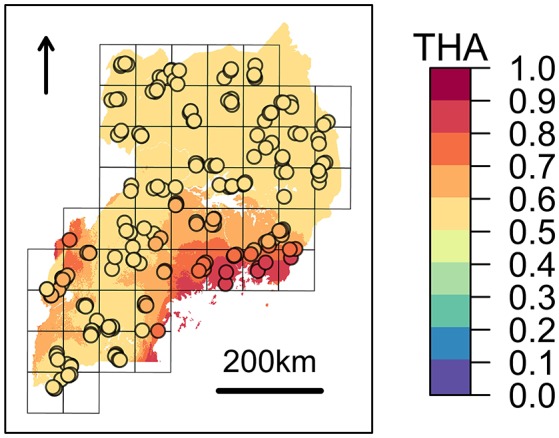

Based on the gene pools revealed by Admixture analysis in Ugandan indigenous cattle, we performed PCAdmix analysis using one zebuine (Tharparkar; THA) and one African taurine (Muturu; MUT) reference (Supplementary Text 4). After QC, LAD counted 689,339 markers and 128 individuals (102 Ugandan cattle individuals, 13 THA, and 13 MUT).

For the genomic window hosting BTA-113604 (i.e., window 13 on chromosome 26; Supplementary Figure 13), 79 out of the 204 haploid individuals targeted showed MUT ancestry, while 125 THA ancestry (Supplementary Figure 14). For the genomic window hosting ARS-110102 and ARS-24867 (i.e., window 145 on chromosome 13; Supplementary Figure 13), 63 haploid individuals were assigned to MUT, while 141 to THA (Supplementary Figure 14).

Beta regression analysis

Tharparkar ancestry at window 13 of chromosome 26 showed a positive and significant association with ψRc (H0: βi=0, α=0.05) (Table 6 and Figure 4), while no significant association was found between the Muturu/Tharparkar ancestries at window 145 of chromosome 13 and γc (Supplementary Text 5).

Table 6.

Beta regression results.

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | p-value | ORa | ORlowb | ORupc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | 0.144 | 0.194 | 4.56E−01 | 1.155 | 0.790 | 1.689 |

| ψRc | 1.663 | 0.768 | 3.04E−02* | 5.275 | 1.171 | 23.767 |

| ϕ | 2.029 | 0.346 |

Association between the inferred proportion of THA ancestry at window 13 (chromosome 26) with average Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability per sampling cell (ψRc). Point estimates (Estimate) of the intercept (β0), the regression coefficient associated to ψRc and the precision parameter ψ are reported on the logit scale together with their standard errors (SE). P-values and odds ratios (OR) are shown for β0 and ψRc. Significant regression coefficients are highlighted with ***when their p-values (p) are ≤ 0.001; **when 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01;

when 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05.

Odds ratio 95% confidence interval (CI), lower bound.

Odds ratio 95% CI, upper bound.

Figure 4.

Expected zebuine proportion of the genomic region candidate for tick resistance. The association inferred through beta regression between Tharparkar ancestry (THA) and average Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability per cell (Table 6) was used to generalize expected zebuine ancestry over Uganda. Colour key corresponds to predicted THA proportion, with increasing values from the blue to the red tones. Sampled farms are represented with circles, and coloured according to the predicted THA proportion at their geographical location.

Discussion

East Coast fever represents a major issue for livestock health in sub-Saharan countries (Nene et al., 2016), with over one million cattle deceased every year, and an annual economic damage of 168–300 million USD (Norval et al., 1992; McLeod and Kristjanson, 1999).

ECF incidence is highly correlated with the geographical distribution of the tick vector R. appendiculatus, whose occurrence is an essential precondition for T. p. parva infection in cattle (Olwoch et al., 2008). However, with the present study we show that areas with predicted poor habitat suitability for the tick can present higher infection rates when compared with regions highly suitable for the tick (Figure 2 and Table 4). Such observation suggests that additional factors may contribute in explaining the observed T. p. parva infection patterns; here, we suggest three possible hypotheses.

First, environmental temperature may play a pivotal role in defining T. p. parva infection risk. Piroplasm development within the tick vector appears to be hindered by temperatures >28°C persisting even for short time periods (as less as 15 days) (Young and Leitch, 1981). Therefore, areas exceeding this temperature threshold might present a reduced infection risk due to the low success in parasite development and transmission. The presence of such a temperature constraint might concur in explaining the low infection risk predicted in the regions such as North-East of Lake Victoria, where a highly suitable habitat is predicted for R. appendiculatus, but where temperature can reach 30°C in the warmest month of the year (January) (Hijmans et al., 2005). Coherently, in the south-western area, environmental temperature ranges between ~8 and 28°C during the whole year (Hijmans et al., 2005), and the predicted risk of infection increases possibly reflecting a higher efficiency in the parasite transmission despite the predicted decrease in tick occurrence probability.

Second, the most suitable areas for the vector (Figure 2A) overlap those regions where the highest levels of zebuine ancestry were recorded (Supplementary Figure 10). B. t. indicus is known to be more effective in counteracting tick infestation than B. t. taurus (Brizuela et al., 1996; Wambura et al., 1998; Mattioli et al., 2000; Jonsson et al., 2014), and is consequently less affected by tick-borne micro-organisms (Mattioli et al., 2000), including T. p. parva, whose effects are known to be dose-dependent (Brossard and Wikel, 1997; Nene et al., 2016). The core adaptive response to tick burden was identified as the inflammatory reaction triggered by the tick bite at the cutaneous level (Mattioli et al., 2000), which activates a strong white cells-mediated cutaneous reaction (Willadsen, 1980) affecting attachment, salivation, engorgement, and ultimately limiting the inoculation of tick-borne microorganisms (Wikel and Bergrnan, 1997). Therefore, the low infection risk observed in the most suitable areas for R. appendiculatus (e.g., north-eastern districts) might be explained by the coexistence of putative tick-resistant zebuine-like populations (Bahbahani et al., 2017), along with a sub-optimal environmental niche for the parasite. Further, we speculate that cattle populations living in regions suitable for T. p. parva development, but with reduced predicted tick burden (e.g., the southern districts; Figures 2A,B), could have not undergone a tick-specific adaptation, and therefore show higher infection rates.

Third, the R. appendiculatus distribution model does not explicitly consider anthropogenic factors like tick-control campaigns on a local and temporal basis. However, adequate tick-control campaigns are rarely undertaken in Uganda (Ugandan National Drug Authority), and evidence of R. appendiculatus developing drug resistance has been recorded (Vudriko et al., 2016).

Despite T. p. parva infection being observed in the northern farms of Uganda, a low tick occurrence probability is predicted for the same regions (ψR<0.1; Figure 2A). A possible explanation is the lack of R. appendiculatus records from these areas, and the consequent bias in the tick distribution model (Cumming, 1999b; Olwoch et al., 2003). Moreover, predicted infection risk in the North (γ<0.3; Figure 2B) may be inflated by the inverse relationship between γ and ψR as estimated by the infection risk model (Table 4), and care is recommended regarding the infection risk predictions for these areas.

Local adaptation is prone to evolve in host-parasite systems, given the strong (and often reciprocal) selection imposed by one species to the other, the reduced role of phenotypic plasticity, and the small number of genes with strong effects usually involved (Kawecki and Ebert, 2004). In a spatial context, a gradient of selection intensity (i.e., spatially varying selection) is required over the landscape, with coexistence areas showing higher selective pressure being candidate for local adaptive responses to evolve. In the present case, host distribution encompasses regions having different selective pressure in terms of both tick and parasite burdens (Figures 2A,B). Regions with higher T. p. parva selective pressure (implying tick occurrence with effective transmission) are those where the host population is expected to be locally adapted to infection; whereas, regions with higher tick burden (but lower infection risk) are those where tick-resistant populations are expected to occur. Following this rational, we suggest that the putative adaptive component sustaining ECF-tolerance/resistance might be due to a synergic mechanism involving specific adaptations to R. appendiculatus and T. p. parva.

Specifically, adaptations to tick burden could be found along the Lake Victoria coasts, where a higher selective pressure linked to R. appendiculatus is predicted (Figure 2A). We identified 41 loci across 18 chromosomes significantly associated with ψR (Figure 3A), with the majority of putative loci under selection found on chromosomes 5 (nine loci), 1 (seven loci), and 15 (three loci). Interestingly, the large genomic region hosting the associated SNPs on chromosome 5 (Supplementary Table 2) overlaps a genomic region which has been previously associated with several traits in tropical cattle, including parasite resistance (Porto-Neto et al., 2014). Among the genes in LD with the associated markers, we found PRKG1 on chromosome 26 (Table 5A and Supplementary Figure 13), a gene coding for an important mediator of vasodilation, and already reported as possibly involved in tick resistance in the South African Nguni breed (see Table 6 in Mapholi et al., 2016). Importantly, vasodilatation is a classical feature of the inflammatory response (Sherwood and Toliver-Kinsky, 2004; Surks, 2007), the core mechanisms underlying tick resistance, as discussed before. None of the remaining annotated genes was easily attributable to adaptation to tick burden (Table 5A).

A specific adaptive response toward T. p. parva infection may have evolved in south-western Uganda, possibly due to ecological conditions more suitable for parasite survival and successful transmission, and the presence of a more tick-susceptible cattle population (Supplementary Figure 10). Theileria parva pathogenicity is linked to its ability to invade host lymphocytes, and promoting their transformation and clonal expansion through the activation of several host-cell signalling pathways (McKeever and Morrison, 1990; Dobbelaere and Küenzi, 2004; Chaussepied et al., 2010). Here, we found seven markers significantly associated with γ, two of which (ARS-110102 and ARS-24867) included within SLA2 genic region on chromosome 13 (Supplementary Figure 13). SLA2 is known to be involved with signal transduction in B and T cells, playing a role into downregulation of humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, and thus contributing to a correct activation and proliferation of lymphocytes (Holland et al., 2001; Kazi et al., 2015; Marton et al., 2015). SLA2 antagonistic effect on lymphocytes proliferation would suggest its putative involvement in opposing the diffusion of T. p. parva in the organism.

Replication studies performed in areas with analogous host characteristics and selective gradients, like Kenya or Tanzania (Giblin, 1990; Gachohi et al., 2012; Laisser et al., 2017), and following the same methodology applied here would allow to validate the generality of the adaptive patterns highlighted, as well as to further control for the confounding effects of population structure and unconsidered collinear environmental features (Rellstab et al., 2015). Further, experimental validation will be essential to finally verify the physiological effect of the identified genes, and thus considering targeted breeding schemes.

Despite the genetic proximity between Muturu and some tick resistant indigenous B. t. taurus breeds of western Africa (i.e., N'Dama) Mattioli et al., 2000; Ibeagha-Awemu et al., 2004, local ancestry of the genomic region candidate for tick resistance was predominantly assigned to Tharparkar (Figure 4, Table 6, and Supplementary Figure 14). This result is in agreement with the known resistance of zebuine cattle to ticks, and suggests the origin of tick resistance in eastern Africa either from imported Indian populations or within local zebuine-like populations after migration from India. Conversely, no easily-interpretable indication was obtained for the genomic region candidate for tolerance to T. p. parva infection. Indeed, neither Tharparkar nor Muturu ancestries displayed a significant association with infection risk, while an additional local ancestry analysis revealed a positive correlation with the European taurine Hereford ancestry when tested versus Tharparkar (Supplementary Text 5). Although surprising, this result would rather point toward a taurine origin of infection tolerance/resistance. However, local ancestry results are inherently reference-dependent (Barbato et al., 2017), and further analyses with different African taurine and zebuine references will be required to disentangle the evolutionary origin of the genomic regions under scrutiny.

Besides the identification of candidate regions for local adaptation, our results revealed allochthonous introgression from Europe within the local gene pools of indigenous Ugandan B. taurus populations (Supplementary Text 4 and Supplementary Figure 10). This finding is consistent with the generalized loss of agro-biodiversity reported worldwide (FAO, 2015; Mwai et al., 2015), and stresses the importance of monitoring local genetic resources to conserve unique adaptations, including tolerance and/or resistance to tropical endemic diseases.

Despite limitations in both epidemiological and species occurrence data, the proposed methodological framework allowed the identification of two candidate genes putatively associated with local adaptation to East Coast fever. Overall, the combination of ecological modelling (i.e., species distribution and infection risk models) and landscape genomics showed the potential of detecting candidate genomic regions showing adaptive significance, and can assist in unravelling the adaptive patterns underlying any kind of symbiotic relationship like host-parasite interactions, mutualism, and commensalism, as well as competition among species.

Data accessibility

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study, as well as the source code developed for data analysis, can be found in the Dryad Digital Repository (doi: 10.5061/dryad.sf5j2bf). Raster data are available from the public sources mentioned in the references and in Supplementary Text 1.

Author contributions

EV, MB, LC, MM, ER, EF, MD, RN, SJ, and PA-M: Conceptualization; EV, MB, LC, and MM: Data curation; EV and MB: Formal analysis; EV, MB, ER, EF, SJ, and PA-M: Methodology; EV, MB, MM, and MD: Software; EV: Visualization, original draft preparation; MB, LC, MM, ER, SJ, TSS, and PA-M: Review and editing; LC, MM, FK, and RN: Investigation; LC, RN, SJ, and PA-M: Funding acquisition; LC, SJ, and PA-M: Supervision; SJ and PA-M: Project administration; CMu, CMa, VBM, FK, TSS, and HJH: Resources.

Conflict of interest statement

TSS was employed by company Recombinetics, Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the NextGen Consortium, and to Graeme S. Cumming, who kindly provided the R. appendiculatus occurrence dataset used in the present study. A previous version of this manuscript appeared as a chapter of the Ph.D. thesis by Vajana (2017), and was released as pre-print to bioRχiv (Vajana et al., 2018).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Cd

Cattle density

- D

Likelihood-ratio test statistic

- |r|

Absolute Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient

- r2

Global linkage disequilibrium decay

- γ

Theileria parva parva infection risk in cattle

- γc

Average γ in the c sampling cell

- πi

Genotype occurrence probability in the i-th individual

- ψ

Species occurrence probability

- ψx

Species occurrence probability in the x pixel of the landscape

- ψR

Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability

- ψRx

Rhipicephalus appendiculatus occurrence probability in the x pixel of the landscape

- ψRc

Average ψR in the c sampling cell

- ψS

Syncerus caffer occurrence probability

- ψSx

Syncerus caffer occurrence probability in the x pixel of the landscape.

1US Geological Survey (USGS). Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center - Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Available at: https://earlywarning.usgs.gov/fews.

Funding. This study makes use of data generated by the NextGen Consortium, coordinated by Dr. Pierre Taberlet. The European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2010-2014) provided funding for the project under grant agreement no 244356–NextGen (Grant KBBE-2009-1-1-03). EV was supported by the Doctoral School on the Agro-Food System (Agrisystem) of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Italy). MM was supported by grant 2016/05787-7, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2018.00385/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aho K., Derryberry D., Peterson T. (2014). Model selection for ecologists: the worldviews of AIC and BIC. Ecology 95, 631–636. 10.1890/13-1452.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aken B. L., Ayling S., Barrell D., Clarke L., Curwen V., Fairley S., et al. (2016). The Ensembl gene annotation system. Database 2016:baw093. 10.1093/database/baw093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. H., Novembre J., Lange K. (2009). Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664. 10.1101/gr.094052.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahbahani H., Hanotte O. (2015). Genetic resistance: tolerance to vector-borne diseases and the prospects and challenges of genomics. Rev. Sci. Tech 34, 185–197. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9dfc/e06d6cf47093061024ff324a013e93cdd7fa.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahbahani H., Tijjani A., Mukasa C., Wragg D., Almathen F., Nash O., et al. (2017). Signatures of selection for environmental adaptation and zebu × taurine hybrid fitness in East African Shorthorn Zebu. Front. Genet. 8:68. 10.3389/fgene.2017.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin C. L., Black S. J., Brown W. C., Conrad P. A., Goddeeris B. M., Kinuthia S. W., et al. (1988). Bovine T cells, B cells, and null cells are transformed by the protozoan parasite Theileria parva. Infect. Immun. 56, 462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato M., Hailer F., Orozco-terWengel P., Kijas J., Mereu P., Cabras P., et al. (2017). Genomic signatures of adaptive introgression from European mouflon into domestic sheep. Sci. Rep. 7:7623. 10.1038/s41598-017-07382-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato M., Orozco-terWengel P., Tapio M., Bruford M. W. (2015). snep: a tool to estimate trends in recent effective population size trajectories using genome-wide SNP data. Front. Genet. 6:109. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barve N., Barve V., Jiménez-Valverde A., Lira-Noriega A., Maher S. P., Peterson A. T., et al. (2011). The crucial role of the accessible area in ecological niche modeling and species distribution modeling. Ecol. Model. 222, 1810–1819. 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billiouw M., Vercruysse J., Marcotty T., Speybroeck N., Chaka G., Berkvens D. (2002). Theileria parva epidemics: a case study in eastern Zambia. Vet. Parasitol. 107, 51–63. 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00089-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter N., Hall R. (1999). Immunity and vaccine development in the bovine theilerioses. Adv. Parasitol. 44, 41–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko A. R., Quignon P., Li L., Schoenebeck J. J., Degenhardt J. D., Lohmueller K. E., et al. (2010). A simple genetic architecture underlies morphological variation in dogs. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000451. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bring J. (1994). How to standardize regression coefficients. Am. Stat. 48, 209–213. 10.2307/2684719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbin A., Bryc K., Byrnes J., Zakharia F., Omberg L., Degenhardt J., et al. (2012). PCAdmix: principal components-based assignment of ancestry along each chromosome in individuals with admixed ancestry from two or more populations. Hum. Biol. 84, 343–364. 10.3378/027.084.0401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizuela C. M., Ortellado C. A., Sanchez T. I., Osorio O., Walker A. R. (1996). Formulation of integrated control of Boophilus microplus in Paraguay: analysis of natural infestations. Vet. Parasitol. 63, 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondyk W. H., McKiernan C. J., Fortner K. A., Stabila P., Holz R. W., Macara I. G. (1995). Interaction cloning of Rabin3, a novel protein that associates with the Ras-like GTPase Rab3A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossard M., Wikel S. K. (1997). Immunology of interactions between ticks and hosts. Med. Vet. Entomol. 11, 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brütting C., Emmer A., Kornhuber M., Staege M. (2016). A survey of endogenous retrovirus (ERV) sequences in the vicinity of multiple sclerosis (MS)-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Mol. Biol. Rep. 43, 827–836. 10.1007/s11033-016-4004-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade B. S. (2015). Model averaging and muddled multimodel inferences. Ecology 96, 2370–2382. 10.1890/14-1639.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaussepied M., Janski N., Baumgartner M., Lizundia R., Jensen K., Weir W., et al. (2010). TGF-b2 induction regulates invasiveness of Theileria-transformed leukocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001197. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIESIN Center for International Earth Science Information Network (2016). Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Land and Water Area. Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC). [Google Scholar]

- Cribari-Neto F., Zeileis A. (2010). Beta regression in R. J. Stat. Softw. 34 10.18637/jss.v034.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crispo E., DiBattista J. D., Correa C., Thibert-Plante X., McKellar A. E., Schwartz A. K., et al. (2010). The evolution of phenotypic plasticity in response to anthropogenic disturbance. Evol. Ecol. Res. 12, 47–66. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/afb5/a4a4bfc20f6c4dc7c40bfbd515e15f66f11e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G. S. (1999a). Host distributions do not limit the species ranges of most African ticks (Acari: Ixodida). Bull. Entomol. Res. 89, 303–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G. S. (1999b). The Evolutionary Ecology of African Ticks. Ph. D. thesis.

- Cumming G. S. (2002). Comparing climate and vegetation as limiting factors for species ranges of african ticks. Ecology 83, 255–268. 10.2307/2680136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decker J. E., McKay S. D., Rolf M. M., Kim J., Molina Alcalá A., Sonstegard T. S., et al. (2014). Worldwide patterns of ancestry, divergence, and admixture in domesticated cattle. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004254. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere D. A., Küenzi P. (2004). The strategies of the Theileria parasite: a new twist in host–pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16, 524–530. 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormann C. F., Elith J., Bacher S., Buchmann C., Carl G., Carré G., et al. (2013). Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 36, 27–46. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein H. (1971). On the Classification of Cattle. The Origin of Domestic Animals of Africa. New York, NY: African Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. S. (2017). spatialEco. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=spatialEco.

- FAO (2015). The Second Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome: FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments; Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4787e/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Frantz L. A., Schraiber J. G., Madsen O., Megens H. J., Cagan A., Bosse M., et al. (2015). Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes. Nat. Genet. 47, 1141–1148. 10.1038/ng.3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D. J., Weir L. K., Bernatchez L., Hansen M. M., Taylor E. B. (2011). Extent and scale of local adaptation in salmonid fishes: review and meta-analysis. Heredity 106, 404–420. 10.1038/hdy.2010.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A. R. (2006). Assessing the relative ages of admixture in the bovine hybrid zones of Africa and the Near East using X chromosome haplotype mosaicism. Genetics 173, 1503–1510. 10.1534/genetics.105.053280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachohi J., Skilton R., Hansen F., Ngumi P., Kitala P. (2012). Epidemiology of East Coast fever (Theileria parva infection) in Kenya: past, present and the future. Parasit Vectors 5:194. 10.1186/1756-3305-5-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachohi J. M., Kitala P. M., Ngumi P. N., Skilton R. A. (2011). Environment and farm factors associated with exposure to Theileria parva infection in cattle under traditional mixed farming system in Mbeere District, Kenya. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 43, 271–277. 10.1007/s11250-010-9688-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galardi S., Fatica A., Bachi A., Scaloni A., Presutti C., Bozzoni I. (2002). Purified Box C/D snoRNPs are able to reproduce site-specific 2'-O-Methylation of target RNA in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6663–6668. 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6663-6668.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBIF (2012). Recommended Practices for Citation of the Data Published Through the GBIF Network. Version 1.0 (Authored by Vishwas Chavan). Copenhagen: Global Biodiversity Information Facility; Available online at: https://www.gbif.org/citation-guidelines [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani S., Tahmoorespur M., Masoudi-Nejad A., Nasiri M., Asgari Y. (2015). Analysis of the enzyme network involved in cattle milk production using graph theory. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 4, 93–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giblin J. L. (1990). East coast fever in socio-historical context: a case study from Tanzania. Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 23, 401–421. 10.2307/219597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert I., Robert C., Vigneault C., Blondin P., Sirard M. A. (2012). Impact of the LH surge on granulosa cell transcript levels as markers of oocyte developmental competence in cattle. Reproduction 143, 735–747. 10.1530/REP-11-0460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass E. J., Jensen K. (2007). Resistance and susceptibility to a protozoan parasite of cattle—gene expression differences in macrophages from different breeds of cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 120, 20–30. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick G., Shirak A., Seroussi E., Zeron Y., Ezra E., Weller J. I., et al. (2011). Fine mapping of a QTL for fertility on BTA7 and its association with a CNV in the Israeli holsteins. GenesGenomesGenetics 1, 65–74. 10.1534/g3.111.000299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanotte O., Bradley D. G., Ochieng J. W., Verjee Y., Hill E. W., Rege J. E. (2002). African pastoralism: genetic imprints of origins and migrations. Science 296, 336–339. 10.1126/science.1069878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan L., Vögeli P., Stoll P., Kramer S. S., Stranzinger G., Neuenschwander S. (2004). Intragenic deletion in the gene encoding L-gulonolactone oxidase causes vitamin C deficiency in pigs. Mamm. Genome 15, 323–333. 10.1007/s00335-003-2324-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida K., Abe T., Weir W., Nakao R., Ito K., Kajino K., et al. (2013). Whole-genome sequencing of Theileria parva strains provides insight into parasite migration and diversification in the African Continent. DNA Res. 20, 209–220. 10.1093/dnares/dst003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiendleder S., Lewalski H., Janke A. (2008). Complete mitochondrial genomes of Bos taurus and Bos indicus provide new insights into intra-species variation, taxonomy and domestication. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 120, 150–156. 10.1159/000118756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R. J. (2016). raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster.

- Hijmans R. J., Cameron S. E., Parra J. L., Jones P. G., Jarvis A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978. 10.1002/joc.1276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S. J., Liao X. C., Mendenhall M. K., Zhou X., Pardo J., Chu P., et al. (2001). Functional cloning of Src-like adapter protein-2 (SLAP-2), a novel inhibitor of antigen receptor signaling. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1263–1276. 10.1084/jem.194.9.1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibeagha-Awemu E. M., Jann O. C., Weimann C., Erhardt G. (2004). Genetic diversity, introgression and relationships among West/Central African cattle breeds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 36, 673–690. 10.1051/gse:2004024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto I., Pimkhaokham A., Watanabe T., Saito-Ohara F., Soeda E., Inazawa J. (2000). Amplification and overexpression of TGIF2, a novel homeobox gene of the TALE superclass, in ovarian cancer cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276, 264–270. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis A., Reuter H. I., Nelson A., Guevara E. (2008). Hole-Filled SRTM for the Globe Version 4, Available From the CGIAR-CSI SRTM 90m Database. Available online at: http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org.

- Jolliffe I. (2002). Principal Component Analysis. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson N. N., Piper E. K., Constantinoiu C. C. (2014). Host resistance in cattle to infestation with the cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus. Parasite Immunol. 36, 553–559. 10.1111/pim.12140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost S., Bonin A., Bruford M. W., Després L, Conord C., Erhardt G., et al. (2007). A spatial analysis method (SAM) to detect candidate loci for selection: towards a landscape genomics approach to adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 16, 3955–3969. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabi F., Masembe C., Muwanika V., Kirunda H., Negrini R. (2014). Geographic distribution of non-clinical Theileria parva infection among indigenous cattle populations in contrasting agro-ecological zones of Uganda: implications for control strategies. Parasit. Vectors 7:414. 10.1186/1756-3305-7-414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawecki T. J., Ebert D. (2004). Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecol. Lett. 7, 1225–1241. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazi J. U., Kabir N. N., Rönnstrand L. (2015). Role of SRC-like adaptor protein (SLAP) in immune and malignant cell signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 2535–2544. 10.1007/s00018-015-1882-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Hanotte O., Mwai O. A., Dessie T., Bashir S., Diallo B., et al. (2017). The genome landscape of indigenous African cattle. Genome Biol. 18:34. 10.1186/s13059-017-1153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss-László Z, Henry Y., Bachellerie J. P., Caizergues-Ferrer M., Kiss T. (1996). Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell 85, 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivaria F. M., Heuer C., Jongejan F., Okello-Onen J., Rutagwenda T., Unger F., et al. (2004). Endemic stability for Theileria parva infections in Ankole calves of the Ankole ranching scheme, Uganda. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 71, 189–195. 10.4102/ojvr.v71i3.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodiha M., Frohlich M., Stochaj U. (2012). Spatial Proteomics Sheds Light on the Biology of Nucleolar Chaperones. Curr. Proteomics 9, 186–216. 10.2174/157016412803251824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar C. C., Mohan S. R., Zavodny P. J., Narula S. K., Leibowitz P. J. (1989). Characterization and differential expression of human vascular smooth muscle myosin light chain 2 isoform in nonmuscle cells. Biochemistry 28, 4027–4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisser E. L., Chenyambuga S. W., Karimuribo E. D., Msalya G., Kipanyula M. J., Mwilawa A. J., et al. (2017). A review on prevalence, control measure, and tolerance of Tanzania Shorthorn Zebu cattle to East Coast fever in Tanzania. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 49, 813–822. 10.1007/s11250-017-1266-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster P. A., Sharman E. D., Horn G. W., Krehbiel C. R., Starkey J. D. (2014). Effect of rate of weight gain of steers during the stocker phase. III. Gene expression of adipose tissues and skeletal muscle in growing–finishing beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 92, 1462–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landin Malt A., Cagliero J., Legent K., Silber J., Zider A., Flagiello D. (2012). Alteration of TEAD1 expression levels confers apoptotic resistance through the transcriptional up-regulation of livin. PLoS ONE 7:e45498. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C., Chiang K. C., Feng T. H., Chen Y. J., Chuang S. T., Tsui K. H., et al. (2016). The iron chelator, Dp44mT, effectively inhibits human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:1435. 10.3390/ijms17091435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee D. A., MacHugh D. E., Edwards C. J. (2014). Interrogation of modern and ancient genomes reveals the complex domestic history of cattle. Anim. Front. 4, 7–22. 10.2527/af.2014-0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magona J. W., Walubengo J., Olaho-Mukani W., Jonsson N. N., Welburn S. C., Eisler M. C. (2008). Clinical features associated with seroconversion to Anaplasma marginale, Babesia bigemina and Theileria parva infections in African cattle under natural tick challenge. Vet. Parasitol. 155, 273–280. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magona J. W., Walubengo J., Olaho-Mukani W., Jonsson N. N., Welburn S. W., Eisler M. C. (2011). Spatial variation of tick abundance and seroconversion rates of indigenous cattle to Anaplasma marginale, Babesia bigemina and Theileria parva infections in Uganda. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 55, 203–213. 10.1007/s10493-011-9456-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoulas C., Zatsepina O. V., Jordan P. W., et al. (1998). The SURF-6 protein is a component of the nucleolar matrix and has a high binding capacity for nucleic acids in vitro. Eur J Cell Biol 75, 174–183. 10.1016/s0171-9335(98)80059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]