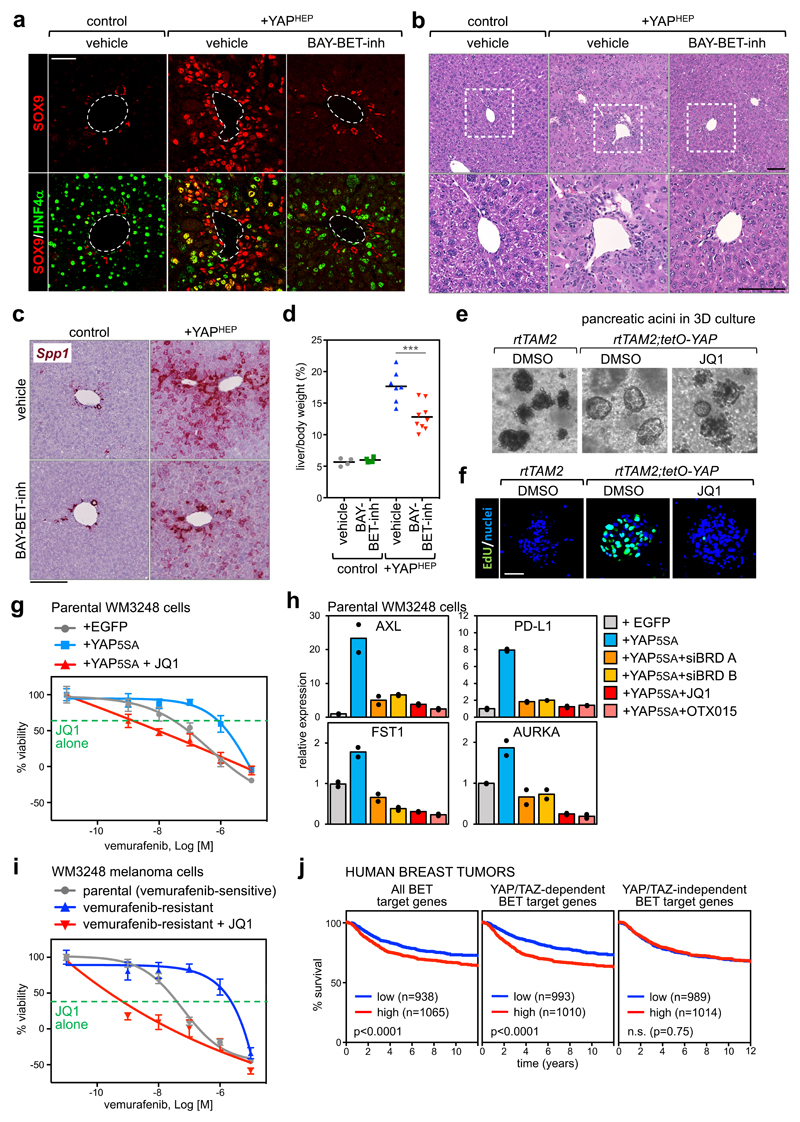

Figure 6. Treatment with BET inhibitors blunts YAP/TAZ-driven responses in vivo.

a) Representative immunofluorescence (IF) for SOX9 and HNF4α in sections of control mouse livers or livers with hepatocyte-specific overexpression of YAPS127A (+YAPHEP), treated with vehicle or BAY-BET-inhibitor. Quantification of double positive cells is in Supplementary Fig. 6c. Scale bar is 50µm. IF was performed in n=4 control mice, n=4 +YAPHEP mice treated with vehicle, and n=4 +YAPHEP mice treated with BAY-BET-inhibitor.

b) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver sections from control mice + vehicle (n=4), +YAPHEP mice + vehicle (n=7), +YAPHEP mice + BAY-BET-inh (n=9). Lower panels are magnifications of the portal area. Scale bars are 100μm. Administration of BET-inhibitor to control mice had no overt consequences on liver morphology or molecular features (see Supplementary Fig. 6f-g).

c) RNA in situ hybridization on liver tissues for Osteopontin (Spp1). Scale bar is 200µm. The experiment was performed in liver sections from 2 mice per each experimental group with similar results.

d) BAY-BET inhibitor impairs liver overgrowth induced by YAP expression. Data are liver/body weight ratios in all examined mice (control mice + vehicle, n=4; control mice + BAY-BET-inh, n=4; +YAPHEP mice + vehicle, n=7; +YAPHEP mice + BAY-BET-inh, n=9). Lines represent the mean of each group. ***p=0.00098 (unpaired t-test, two-tailed)

e) Representative images of pancreatic acini in 3D culture, derived from the indicated mice, after 3 days of culture in the presence of doxycycline to activate YAP expression. Treatment with BET inhibitor opposes YAP-induced ADM in organoids (see quantification in Supplementary Fig. 6i). The experiment was repeated four times with similar results.

f) EdU staining showing as treatment with BET inhibitor impairs cell proliferation. Scale bar is 50 μm. The experiment was repeated two times with similar results.

g) Viability curves of parental WM3248 cells (per se vemurafenib-sensitive) transduced with EGFP or YAP5SA, treated with increasing doses of vemurafenib (1nM to 10µM) with or without JQ1(1µM). The green line shows the effect of JQ1 alone (1µM). Data are mean + SD of n=8 independent wells (independently treated and evaluated). One representative experiment is shown; similar results were obtained in two additional independent experiments.

h) RT-qPCR for YAP/TAZ target genes showing upregulation upon YAP5SA overexpression in WM3248 cells and downregulation upon treatment with BET inhibitors (1µM, 24h) or depletion of BRD2/3/4 (siBRD mix A and B). Data are presented as individual data points (n=2 independent samples) + average (bar).

i) Viability curves of parental (vemurafenib-sensitive) WM3248 and vemurafenib-resistance WM3248, treated with increasing doses of vemurafenib (1nM to 10µM) with or without JQ1(1µM). The green line shows the effect of JQ1 alone (1µM). Data are presented as in g. One of three independent experiments (all with similar results) is shown.

j) Kaplan–Meier graph representing the probability of metastasis-free survival in breast cancer patients. Survival curves are significantly different when patients are stratified according to high or low expression of all BET target genes and common YAP/TAZ/BET target genes, but not when patients are stratified according to BET-only targets (Log-rank Mantel Cox Test).