Abstract

Background:

The Canadian government has committed to an endgame target of less than 5% tobacco use by 2035. The aims of this study were to assess baseline levels of support for potential endgame policies among Canadian smokers, by province/region, demographic characteristics and smoking-related correlates, and to identify predictors of support.

Methods:

We analyzed data for 3215 adult (age ≥ 18 yr) smokers from the Canadian arm of the 2016 International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. We estimated weighted percentages of support for endgame measures for 6 provinces/regions of the country. We used weighted logistic regression models to identify predictors of support for 14 endgame strategies.

Results:

Among cigarette endgame policies, support was highest for reducing nicotine content (70.2%), raising the legal age for purchase (69.8%), increasing access to alternative nicotine products (65.8%) and banning marketing (58.5%). Among e-cigarette policies, there was majority support for restricting youth access (86.1%), restricting nicotine content (64.9%), prohibiting use in smoke-free places (63.4%) and banning marketing (54.8%). The level of support for other endgame measures ranged from 28.9% to 45.2%. Support for cigarette and e-cigarette policies was generally higher among smokers with intentions to quit and those from Quebec. Support for e-cigarette policies was generally lower among smokers who also used e-cigarettes daily.

Interpretation:

There is considerable support among Canadian smokers for endgame policies that go beyond current approaches to tobacco control. Our findings provide a baseline for evaluating future trends in smokers’ support for innovative measures to radically reduce smoking rates in Canada.

Tobacco use is the leading cause of premature death in the world, resulting in more than 6 million preventable deaths globally each year.1,2 In Canada, where cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product, the smoking rate among youth and adults (age ≥ 15 yr) decreased from 15.0% in 2013 to an all-time low of 13.0% in 2015;3 however, smoking remains the leading cause of preventable disease and premature death.3–5 In 2012, the total economic burden of smoking in Canada was estimated at $16.2 billion, with $6.5 billion in direct health care costs.6

Canada has a long history of leadership in tobacco control. Before ratifying the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, in 2004, Canada was already the first country to have implemented pictorial health warnings, in 2001. Canada has also implemented leading-edge product regulations, including a ban on all flavourings in cigarettes (except menthol) in 2010 and a ban on menthol in 2017.7,8 However, achieving further reductions in smoking prevalence is an increasing challenge. Currently, Canada’s smoking prevalence is estimated to decrease only from 13% to 9% by 2036.9 Over the next 2 decades, smoking rates in Ontario are expected to decrease by less than half, whereas the number of smoking-attributable deaths will increase, even if all 6 key demand-reduction tobacco control measures identified by the World Health Organization are fully implemented.10 The 6 measures, known as the MPOWER package, consist of effective strategies to Monitor tobacco use and policies, Protect people from tobacco smoke, Offer to help to quit tobacco use, Warn about dangers of tobacco, Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship, and Raise tobacco taxes.

To reduce the devastating toll of tobacco on the health, economy and social welfare of Canada, the government is considering tobacco endgame strategies. The tobacco endgame concept emphasizes the need for innovative policy solutions to end the tobacco epidemic within a specific time.11–13 Several countries recently set aggressive targets to drive smoking prevalence down toward zero.14–17 In September 2016, the Canadian Tobacco Endgame Summit convened leading public health and policy experts to discuss an endgame strategy for Canada that would reduce the rate of tobacco use to less than 5% by 2035.18,19 The Canadian government has adopted the goal of less than 5% by 2035 in its ongoing development of a new federal Tobacco Control Strategy.20 Although public support does not always lead to policy implementation, there is evidence that public opinion can influence policy change.21 Canadian research suggests that the government is more responsive in domains where public awareness of and support for policy change are high22,23 and on issues that are important to Canadians.24,25 Public support is likely to play a central role in driving government actions to ensure that endgame proposals are adopted as laws.26,27 Data on public opinions toward endgame ideas in Canada, particularly among smokers, who would be most directly affected by new legislation, are limited. Previous studies conducted in Ontario showed that, in 2000, 56.0% of adults agreed that cigarettes were too dangerous to be sold at all,28 and, in 1996, 46.9% of adult smokers supported a total ban on tobacco advertising.29 We carried out an exploratory study to determine baseline estimates of support among a national cohort of Canadian adult smokers for 1) tobacco marketing and sales bans, 2) restrictions on the content of tobacco products, 3) restrictions on access to tobacco products/alternative nicotine products and 4) restrictions on youth access to e-cigarettes and on their content, use in smoke-free places and promotion.

Methods

Source of data

We analyzed Canadian data from Wave 1 of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey (data collected from July to November 2016).30–32 This survey is an expansion of a cohort survey designed to evaluate the psychosocial and behavioural impact of tobacco control policies on nationally representative samples of adult smokers (age ≥ 18 yr) in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States followed roughly yearly from 2002 to 2014.

Study design and participants

Full details about the study design and sampling frames are described elsewhere30–32 and are available online.33 Methodological details (compliant with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys34) are provided in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E412/suppl/DC1). In brief, the survey was developed by means of a systematic approach comprising 2 phases: 1) a series of teleconferences with research investigators and project and survey management teams to draft the survey (Sept. 23, 2015, to Feb. 1, 2016) and 2) operationalization of survey development, during which routing, question wording, response options and all other survey elements were finalized for programming and testing (Feb. 1 to Apr. 29, 2016). Many survey questions are standard measures that have been previously validated and are commonly used.35–40 Extensive testing of the programmed questionnaire was also conducted before the launch of the fieldwork, in July 2016.

The sample comprised the following cohorts: 1) recontact smokers and quitters who participated in the 2014 survey (n = 567), 2) newly recruited current smokers and recent quitters (quit smoking in the previous 2 yr) (n = 2336) and 3) newly recruited current e-cigarette users (use at least weekly) (n = 830). An a priori power analysis was used to determine the optimal sample size. The sample was designed to be representative of smokers in the Canadian provinces. Based on the criterion most commonly used in self-report tobacco surveillance surveys, including those conducted by Health Canada, current smokers were defined as those who smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime41,42 and currently smoked at least monthly. Current e-cigarette users were defined as those who currently used e-cigarettes at least weekly. Grouping categories are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic and smoking characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristic | Unweighted no. (%) of respondents n = 3215 |

|---|---|

| Province/region | |

| Atlantic* | 227 (7.1) |

| Quebec | 743 (23.1) |

| Ontario | 1268 (39.4) |

| Prairie† | 224 (7.0) |

| Alberta | 355 (11.0) |

| British Columbia | 398 (12.4) |

| Recruitment source | |

| International Tobacco Control Project cohort recruited by randomdigit dialing | 321 (10.0) |

| LegerWeb panel | 2894 (90.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 1697 (52.8) |

| Male | 1518 (47.2) |

| Age group, yr | |

| 18–24 | 760 (23.6) |

| 25–39 | 829 (25.8) |

| 40–54 | 895 (27.8) |

| ≥ 55 | 731 (22.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 2572 (80.0) |

| Other | 588 (18.3) |

| Missing | 55 (1.7) |

| Household income | |

| Low (< $30 000) | 719 (22.4) |

| Moderate ($30 000–$44 999) | 923 (28.7) |

| High (≥ $45 000) | 1338 (41.6) |

| No answer | 235 (7.3) |

| Education level | |

| Low (high school or less) | 933 (29.0) |

| Moderate (technical/trades/college/some university) | 1403 (43.6) |

| High (completed university/postgraduate) | 851 (26.5) |

| Missing | 28 (0.9) |

| Smoking status | |

| Less than daily smoker | 995 (30.9) |

| Daily smoker | 2220 (69.0) |

| E-cigarette use status | |

| Never tried | 914 (28.4) |

| Tried but does not currently use | 476 (14.8) |

| Less than weekly user | 1093 (34.0) |

| Weekly user | 417 (13.0) |

| Daily user | 315 (9.8) |

Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Using stratified sampling across 14 regions, the investigators recruited recontact respondents by random-digit dialing (2002–2011 surveys) or from the LegerWeb panel (representative of the Canadian population across age, sex, geographic region and socioeconomic status; https://legerweb.com/EN-ca/home.asp?) (2013–2014 survey). Newly recruited respondents for the 2016 survey were recruited from the LegerWeb panel. Sampling weights were computed for all respondents to ensure they were representative of the Canadian population of smokers and e-cigarette users. Respondents were categorized into 1 of 4 user groups (cigarette only smokers, e-cigarette only users, dual users and quitters), and weights were calibrated to target figures from the 2015 Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey.3 Respondents completed surveys in English or French using assisted telephone interviews or on the Web.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were self-reported responses to 14 questions on support for endgame measures (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E412/suppl/DC1). The questions used in this study are a subset of the complete International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Predictors of support included province/region of residence, recruitment source, sex, age, ethnicity, annual household income, education level, smoking status and e-cigarette use status. Owing to small samples in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, these provinces were combined into the “Atlantic” region, and Manitoba and Saskatchewan were combined into the “Prairie” region.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the demographic characteristics of the sample using unweighted descriptive statistics. We then estimated weighted percentages of support for endgame measures for 6 provinces/regions of Canada by cross-tabulating province/region with each endgame measure. We estimated standard errors using Taylor series linearization to account for the stratified sampling design. We estimated design-based confidence intervals using the logit method, tested differences in support by demographic characteristics, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status and daily consumption (number of cigarettes per day), and tested intentions to quit smoking using the Wald χ2 omnibus test. We used weighted multivariable logistic regression models to examine the demographic and behavioural factors associated with support for each endgame measure. Regression models controlled for smokers’ perceptions of societal attitudes toward smoking and belief that smokers are increasingly marginalized. All analyses were conducted with the use of SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

Research ethics approval for the survey was obtained from the University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario.

Results

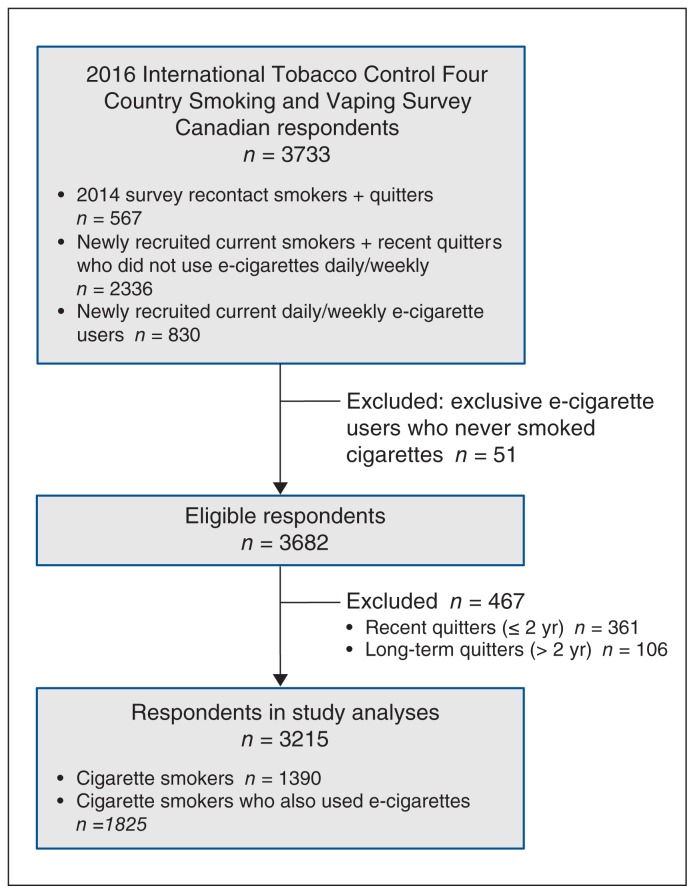

A total of 3733 respondents completed the survey. The analyses presented here are based on 3215 current smokers (1390 cigarette smokers and 1825 users of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes). Exclusive e-cigarette users (n = 51) and those who had quit smoking cigarettes (n = 467) were excluded (Figure 1). The survey cooperation rate (91.1%) and response rate (19.1%) were within the typical range for online surveys. 34 Less than 5% of data were missing for each of the 14 outcome measures. Table 1 presents the unweighted demographic and smoking characteristics of the sample. Overall, the majority of respondents were from Ontario and Quebec, white, from high-income households and daily smokers.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram showing selection of smokers from the Canadian arm of the 2016 International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey for inclusion in the study.

Overall policy support

Over half of the respondents supported 8 of the 14 endgame measures. Among cigarette endgame policies, support was highest for measures to reduce nicotine content (70.2%), raise the legal age for purchase (69.8%) and require retailers to sell alternative nicotine products (65.8%). There was moderate support for a marketing ban (58.5%), restrictions on places for purchase (45.2%), total ban within 10 years (43.6%) and ban on additives/flavourings (42.5%). Support was lowest for a menthol ban (29.6%) and plain packaging (28.9%) (Appendix 3, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E412/suppl/DC1).

Among e-cigarette endgame policies, support was highest for policies to require the same minimum age for buying e-cigarettes as for cigarettes (86.1%). There was majority support to restrict nicotine content (64.9%), ban use in smoke-free places (63.4%) and ban promotion (54.8%). Support was lowest for a ban on fruit/candy flavours (39.8%) (Appendix 3).

Factors associated with support for endgame measures

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 present the results of the weighted multiple logistic regression models of predictors for each of the 14 endgame policies as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, controlling for demographic covariates, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status, daily cigarette consumption, plans to quit smoking, perceptions of societal attitudes towards smoking, and beliefs that smokers are increasingly marginalized. Differences in the sample size between models are due to the fact that only respondents with complete data for all covariates and outcome measures were included. Overall, intentions to quit smoking, e-cigarette use and province/region were significant predictors of support.

Table 2:

Factors associated with support for tobacco marketing and sales bans

| Factor | Ban on promotional marketing of cigarettes/tobacco* n = 3009 |

Total ban on cigarettes/tobacco within 10 yr if government provides cessation assistance* n = 3013 |

Require sale of cigarettes in plain packages* n = 3018 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 56.0 | 1.00 | 42.2 | 1.00 | 28.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 60.1 | 1.14 (0.95–1.36) | 44.6 | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) | 29.1 | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) |

|

| ||||||

| Age group, yr | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 18–24 | 62.9 | 1.00 | 44.0 | 1.00 | 38.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 25–39 | 60.7 | 0.84 (0.64–1.11) | 47.6 | 1.28 (0.98–1.67) | 31.2 | 0.78 (0.59–1.02) |

|

| ||||||

| 40–54 | 57.0 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 42.2 | 1.09 (0.83–1.44) | 28.9 | 0.75 (0.57–1.00) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 55 | 55.7 | 0.82 (0.61–1.11) | 40.8 | 1.15 (0.86–1.54) | 21.7 | 0.56 (0.40–0.77) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| White | 58.0 | 1.00 | 42.3 | 1.00 | 27.9 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 61.1 | 1.01 (0.78–1.32) | 50.6 | 1.39 (1.07–1.79) | 34.2 | 1.23 (0.94–1.60) |

|

| ||||||

| Household income | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 52.5 | 1.00 | 41.9 | 1.00 | 29.4 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 58.5 | 1.13 (0.87–1.46) | 45.0 | 1.06 (0.82–1.37) | 29.0 | 1.03 (0.78–1.37) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 62.7 | 1.22 (0.95–1.57) | 44.5 | 1.07 (0.84–1.38) | 30.0 | 1.04 (0.79–1.38) |

|

| ||||||

| No answer | 45.9 | 0.77 (0.53–1.12) | 36.2 | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | 18.4 | 0.61 (0.39–0.96) |

|

| ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 50.0 | 1.00 | 41.5 | 1.00 | 27.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 57.3 | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) | 43.7 | 1.00 (0.81–1.24) | 27.4 | 0.95 (0.74–1.21) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 69.0 | 1.73 (1.32–2.27) | 45.6 | 1.02 (0.78–1.32) | 32.9 | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) |

|

| ||||||

| Province/region | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quebec | 69.4 | 1.00 | 50.1 | 1.00 | 37.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Atlantic | 58.6 | 0.65 (0.44–0.95) | 43.2 | 0.73 (0.50–1.06) | 29.2 | 0.71 (0.47–1.09) |

|

| ||||||

| Ontario | 53.8 | 0.49 (0.38–0.62) | 43.7 | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 26.9 | 0.60 (0.47–0.77) |

|

| ||||||

| Prairie | 58.0 | 0.63 (0.43–0.91) | 43.2 | 0.79 (0.54–1.17) | 20.2 | 0.43 (0.28–0.68) |

|

| ||||||

| Alberta | 47.9 | 0.37 (0.26–0.51) | 30.8 | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) | 21.0 | 0.44 (0.31–0.63) |

|

| ||||||

| British Columbia | 60.9 | 0.66 (0.48–0.91) | 44.6 | 0.78 (0.57–1.05) | 30.3 | 0.70 (0.50–0.96) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Less than daily smoker | 70.2 | 1.00 | 50.5 | 1.00 | 37.1 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Daily smoker | 53.9 | 0.57 (0.45–0.74) | 40.9 | 0.58 (0.46–0.74) | 25.7 | 0.62 (0.48–0.80) |

|

| ||||||

| E-cigarette use status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Never tried | 59.7 | 1.00 | 44.1 | 1.00 | 26.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Tried but does not currently use | 54.3 | 0.80 (0.61–1.05) | 38.0 | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | 23.6 | 0.86 (0.63–1.17) |

|

| ||||||

| Less than weekly user | 59.1 | 0.85 (0.68–1.07) | 43.2 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 31.2 | 1.06 (0.83–1.37) |

|

| ||||||

| Weekly user | 59.5 | 0.89 (0.65–1.22) | 53.8 | 1.38 (1.03–1.86) | 38.7 | 1.54 (1.12–2.11) |

|

| ||||||

| Daily user | 59.3 | 0.83 (0.57–1.20) | 54.8 | 1.39 (0.99–1.95) | 41.9 | 1.63 (1.15–2.32) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of cigarettes per day | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 10 | 64.9 | 1.00 | 45.7 | 1.00 | 32.4 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 11–20 | 52.4 | 0.78 (0.61–0.98) | 40.5 | 1.03 (0.81–1.31) | 24.6 | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) |

|

| ||||||

| 21–30 | 46.9 | 0.64 (0.47–0.88) | 42.9 | 1.17 (0.85–1.61) | 24.4 | 0.98 (0.68–1.41) |

|

| ||||||

| > 30 | 49.8 | 0.85 (0.44–1.64) | 40.2 | 1.12 (0.58–2.18) | 28.7 | 1.17 (0.57–2.39) |

|

| ||||||

| Plans to quit in next 6 mo | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 50.0 | 1.00 | 30.5 | 1.00 | 25.1 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 61.6 | 1.92 (1.56–2.36) | 48.4 | 2.40 (1.94–2.96) | 30.3 | 1.34 (1.07–1.69) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Logistic regression models controlled for sex, age group, ethnicity, household income, education level, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, plans to quit in next 6 months, perception of societal attitudes toward smoking and belief that smokers are increasingly marginalized.

Table 3:

Factors associated with support for restrictions on contents of tobacco products

| Factor | Reduce nicotine in cigarettes/tobacco to make them less addictive* n = 3018 |

Ban all additives and flavourings in cigarettes/tobacco* n = 3005 |

Ban menthol in cigarettes/tobacco* n = 3000 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 72.3 | 1.00 | 39.6 | 1.00 | 23.7 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 68.8 | 0.81 (0.67–0.97) | 44.4 | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | 33.5 | 1.62 (1.34–1.96) |

|

| ||||||

| Age group, yr | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 18–24 | 71.9 | 1.00 | 36.7 | 1.00 | 32.0 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 25–39 | 70.6 | 0.99 (0.74–1.32) | 38.4 | 1.18 (0.90–1.55) | 28.8 | 0.94 (0.70–1.25) |

|

| ||||||

| 40–54 | 69.3 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 44.8 | 1.75 (1.32–2.30) | 30.6 | 1.17 (0.87–1.57) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 55 | 69.9 | 1.18 (0.86–1.62) | 46.9 | 2.05 (1.53–2.75) | 28.2 | 1.17 (0.85–1.62) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| White | 70.0 | 1.00 | 42.0 | 1.00 | 28.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 71.4 | 1.11 (0.84–1.48) | 45.2 | 1.14 (0.88–1.46) | 35.7 | 1.28 (0.98–1.68) |

|

| ||||||

| Household income | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 66.2 | 1.00 | 40.9 | 1.00 | 29.6 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 71.1 | 1.19 (0.91–1.56) | 45.2 | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 32.1 | 1.08 (0.82–1.41) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 72.2 | 1.28 (0.98–1.67) | 42.4 | 0.94 (0.73–1.20) | 29.4 | 0.92 (0.71–1.21) |

|

| ||||||

| No answer | 63.5 | 0.85 (0.57–1.27) | 35.4 | 0.78 (0.53–1.15) | 19.0 | 0.64 (0.41–1.01) |

|

| ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 67.6 | 1.00 | 43.2 | 1.00 | 28.3 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 70.0 | 0.99 (0.78–1.24) | 39.9 | 0.77 (0.62–0.95) | 29.1 | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 73.0 | 1.06 (0.79–1.41) | 46.3 | 0.96 (0.74–1.24) | 31.9 | 0.99 (0.75–1.31) |

|

| ||||||

| Province/region | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quebec | 76.9 | 1.00 | 44.3 | 1.00 | 35.4 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Atlantic | 72.8 | 0.81 (0.54–1.23) | 41.6 | 0.89 (0.62–1.29) | 27.6 | 0.69 (0.46–1.03) |

|

| ||||||

| Ontario | 69.6 | 0.67 (0.52–0.86) | 43.9 | 0.96 (0.77–1.21) | 29.6 | 0.76 (0.59–0.97) |

|

| ||||||

| Prairie | 64.1 | 0.53 (0.36–0.79) | 48.5 | 1.31 (0.90–1.89) | 24.7 | 0.66 (0.43–1.01) |

|

| ||||||

| Alberta | 62.3 | 0.46 (0.32–0.65) | 32.0 | 0.57 (0.41–0.80) | 21.1 | 0.48 (0.33–0.70) |

|

| ||||||

| British Columbia | 68.6 | 0.61 (0.43–0.85) | 43.1 | 0.94 (0.69–1.28) | 32.1 | 0.88 (0.63–1.21) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Less than daily smoker | 75.1 | 1.00 | 46.9 | 1.00 | 36.4 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Daily smoker | 68.3 | 0.73 (0.56–0.96) | 40.8 | 0.76 (0.60–0.97) | 27.0 | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) |

|

| ||||||

| E-cigarette use status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Never tried | 70.1 | 1.00 | 45.9 | 1.00 | 31.1 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Tried but does not currently use | 66.5 | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) | 38.5 | 0.81 (0.62–1.05) | 20.9 | 0.61 (0.45–0.83) |

|

| ||||||

| Less than weekly user | 71.8 | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 40.5 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 30.3 | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) |

|

| ||||||

| Weekly user | 72.1 | 1.08 (0.78–1.49) | 42.6 | 0.94 (0.70–1.28) | 37.3 | 1.27 (0.93–1.75) |

|

| ||||||

| Daily user | 71.6 | 1.01 (0.70–1.45) | 46.5 | 1.05 (0.76–1.47) | 39.7 | 1.31 (0.91–1.87) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of cigarettes per day | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 10 | 73.0 | 1.00 | 45.7 | 1.00 | 33.3 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 11–20 | 69.2 | 0.93 (0.72–1.19) | 38.8 | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | 25.4 | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) |

|

| ||||||

| 21–30 | 61.4 | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) | 39.0 | 0.68 (0.49–0.94) | 24.2 | 0.70 (0.49–1.00) |

|

| ||||||

| > 30 | 62.1 | 0.71 (0.37–1.36) | 37.5 | 0.61 (0.33–1.16) | 27.2 | 0.74 (0.37–1.50) |

|

| ||||||

| Plans to quit in next 6 mo | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 62.0 | 1.00 | 34.8 | 1.00 | 21.4 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 73.2 | 1.76 (1.42–2.18) | 45.3 | 1.82 (1.48–2.24) | 32.6 | 2.01 (1.58–2.55) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Logistic regression models controlled for sex, age group, ethnicity, household income, education level, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, plans to quit in next 6 months, perception of societal attitudes toward smoking and belief that smokers are increasingly marginalized.

Table 4:

Factors associated with support for restrictions on access to tobacco products/alternative nicotine products

| Factor | Raise legal age for cigarette purchase to ≥ 21 yr* n = 3017 |

Restrict places where cigarettes/tobacco can be purchased* n = 3015 |

Require retail locations to sell alternative nicotine products such as e-cigarettes* n = 3018 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 71.1 | 1.00 | 45.1 | 1.00 | 69.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 68.9 | 0.83 (0.69–1.01) | 45.2 | 0.95 (0.80–1.13) | 63.4 | 0.71 (0.59–0.85) |

|

| ||||||

| Age group, yr | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 18–24 | 58.4 | 1.00 | 47.0 | 1.00 | 70.9 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 25–39 | 72.8 | 2.00 (1.52–2.65) | 50.2 | 1.25 (0.96–1.64) | 68.9 | 0.96 (0.71–1.28) |

|

| ||||||

| 40–54 | 74.3 | 2.43 (1.82–3.24) | 46.0 | 1.32 (1.00–1.73) | 66.4 | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 55 | 66.6 | 1.84 (1.36–2.50) | 38.1 | 1.17 (0.87–1.58) | 59.6 | 0.69 (0.51–0.94) |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| White | 69.2 | 1.00 | 44.1 | 1.00 | 64.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Other | 72.6 | 1.22 (0.91–1.62) | 51.1 | 1.06 (0.81–1.39) | 71.3 | 1.42 (1.07–1.90) |

|

| ||||||

| Household income | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 64.2 | 1.00 | 39.0 | 1.00 | 62.3 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 72.6 | 1.29 (0.98–1.68) | 44.5 | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) | 69.5 | 1.48 (1.13–1.94) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 71.0 | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 49.6 | 1.20 (0.93–1.54) | 66.7 | 1.35 (1.04–1.76) |

|

| ||||||

| No answer | 65.6 | 0.90 (0.61–1.34) | 35.6 | 0.81 (0.54–1.21) | 53.6 | 0.69 (0.47–1.01) |

|

| ||||||

| Education level | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 65.6 | 1.00 | 37.9 | 1.00 | 65.6 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Moderate | 69.7 | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) | 43.8 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 65.0 | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 74.1 | 1.22 (0.93–1.62) | 55.0 | 1.43 (1.10–1.85) | 67.4 | 1.04 (0.74–1.37) |

|

| ||||||

| Province/region | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quebec | 69.0 | 1.00 | 44.8 | 1.00 | 69.3 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Atlantic | 75.1 | 1.31 (0.88–1.96) | 50.1 | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 71.6 | 1.13 (0.77–1.66) |

|

| ||||||

| Ontario | 70.0 | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) | 43.5 | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) | 66.3 | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) |

|

| ||||||

| Prairie | 70.5 | 1.09 (0.72–1.65) | 51.5 | 1.39 (0.94–2.05) | 57.9 | 0.60 (0.41–0.88) |

|

| ||||||

| Alberta | 66.9 | 0.83 (0.58–1.17) | 40.4 | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 59.9 | 0.65 (0.46–0.91) |

|

| ||||||

| British Columbia | 69.2 | 0.88 (0.63–1.22) | 48.4 | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | 65.0 | 0.73 (0.52–1.01) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Less than daily smoker | 73.2 | 1.00 | 62.6 | 1.00 | 63.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Daily smoker | 68.4 | 0.75 (0.58–0.97) | 38.4 | 0.44 (0.34–0.56) | 66.6 | 1.05 (0.82–1.35) |

|

| ||||||

| E-cigarette use status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Never tried | 70.2 | 1.00 | 43.8 | 1.00 | 58.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Tried but does not currently use | 65.6 | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) | 38.5 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 65.5 | 1.32 (1.01–1.73) |

|

| ||||||

| Less than weekly user | 71.4 | 1.15 (0.90–1.47) | 48.9 | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 71.2 | 1.70 (1.35–2.15) |

|

| ||||||

| Weekly user | 71.4 | 1.15 (0.83–1.59) | 49.8 | 1.31 (0.97–1.76) | 76.6 | 2.20 (1.58–3.08) |

|

| ||||||

| Daily user | 69.5 | 1.03 (0.71–1.50) | 50.3 | 1.32 (0.91–1.93) | 74.6 | 1.90 (1.29–2.78) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of cigarettes per day | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 10 | 71.4 | 1.00 | 54.1 | 1.00 | 64.6 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| 11–20 | 70.1 | 1.00 (0.78–1.29) | 38.7 | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) | 66.6 | 1.23 (0.96–1.57) |

|

| ||||||

| 21–30 | 62.0 | 0.71 (0.50–0.99) | 24.9 | 0.43 (0.30–0.60) | 67.4 | 1.32 (0.95–1.85) |

|

| ||||||

| > 30 | 64.1 | 0.85 (0.45–1.61) | 28.3 | 0.57 (0.28–1.14) | 76.6 | 2.22 (1.05–4.66) |

|

| ||||||

| Plans to quit in next 6 mo | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 61.8 | 1.00 | 37.3 | 1.00 | 58.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Yes | 72.7 | 1.72 (1.39–2.13) | 48.1 | 1.95 (1.57–2.43) | 68.4 | 1.36 (1.10–1.67) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Logistic regression models controlled for sex, age group, ethnicity, household income, education level, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, plans to quit in next 6 months, perception of societal attitudes toward smoking and belief that smokers are increasingly marginalized.

Table 5:

Factors associated with support for e-cigarette policies

| Factor | Require same minimum age for buying e-cigarettes as for cigarettes* n = 2996 |

Restrict nicotine in e-cigarettes/e-liquid* n = 2986 |

Ban e-cigarette use in smoke-free places* n = 2997 |

Ban e-cigarette/e-liquid promotion* n = 2999 |

Ban fruit- and candy-flavoured e-cigarettes* n = 2996 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | % support | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Female | 86.7 | 1.00 | 65.9 | 1.00 | 64.2 | 1.00 | 53.5 | 1.00 | 36.9 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Male | 85.6 | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | 64.2 | 0.87 (0.72–1.04) | 62.8 | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 55.7 | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 41.8 | 1.13 (0.94–1.35) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Age group, yr | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 18–24 | 83.2 | 1.00 | 64.0 | 1.00 | 59.9 | 1.00 | 51.7 | 1.00 | 27.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 25–39 | 83.0 | 1.00 (0.70–1.43) | 67.1 | 1.14 (0.86–1.51) | 66.4 | 1.20 (0.91–1.59) | 52.7 | 0.89 (0.68–1.16) | 34.0 | 1.15 (0.86–1.54) |

|

| ||||||||||

| 40–54 | 88.8 | 1.70 (1.16–2.50) | 66.2 | 1.23 (0.93–1.64) | 64.0 | 1.13 (0.86–1.50) | 56.6 | 1.13 (0.86–1.48) | 43.5 | 1.75 (1.31–2.34) |

|

| ||||||||||

| ≥ 55 | 87.4 | 1.49 (1.00–2.22) | 61.4 | 1.07 (0.79–1.45) | 61.1 | 1.08 (0.80–1.45) | 56.4 | 1.21 (0.90–1.63) | 47.1 | 2.08 (1.52–2.83) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| White | 86.0 | 1.00 | 64.3 | 1.00 | 63.2 | 1.00 | 55.7 | 1.00 | 40.2 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Other | 86.4 | 1.26 (0.87–1.80) | 67.9 | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) | 64.3 | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | 49.8 | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | 37.5 | 1.01 (0.77–1.32) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Household income | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Low | 82.9 | 1.00 | 57.0 | 1.00 | 55.0 | 1.00 | 45.9 | 1.00 | 35.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Moderate | 86.8 | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | 69.1 | 1.55 (1.19–2.01) | 62.3 | 1.24 (0.96–1.60) | 57.0 | 1.44 (1.11–1.85) | 42.1 | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) |

|

| ||||||||||

| High | 87.2 | 1.18 (0.84–1.66) | 67.2 | 1.28 (0.99–1.64) | 67.5 | 1.45 (1.13–1.86) | 59.1 | 1.44 (1.12–1.84) | 41.9 | 1.01 (0.78–1.31) |

|

| ||||||||||

| No answer | 85.1 | 0.98 (0.58–1.68) | 53.5 | 0.77 (0.52–1.15) | 64.8 | 1.45 (0.98–2.15) | 42.3 | 0.82 (0.56–1.19) | 26.7 | 0.57 (0.37–0.87) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Low | 85.1 | 1.00 | 60.9 | 1.00 | 60.5 | 1.00 | 48.8 | 1.00 | 35.9 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Moderate | 86.4 | 0.90 (0.66–1.22) | 64.2 | 0.96 (0.78–1.20) | 62.5 | 0.94 (0.75–1.17) | 53.5 | 1.08 (0.87–1.34) | 38.7 | 1.04 (0.83–1.30) |

|

| ||||||||||

| High | 86.6 | 0.84 (0.58–1.22) | 70.1 | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 67.8 | 1.02 (0.78–1.35) | 63.3 | 1.53 (1.17–2.00) | 45.7 | 1.42 (1.09–1.85) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Province/region | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Quebec | 88.7 | 1.00 | 70.9 | 1.00 | 65.2 | 1.00 | 64.4 | 1.00 | 41.8 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Atlantic | 86.1 | 0.78 (0.47–1.29) | 66.7 | 0.85 (0.58–1.26) | 65.0 | 0.94 (0.64–1.39) | 54.2 | 0.61 (0.42–0.90) | 45.0 | 1.07 (0.72–1.59) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Ontario | 84.4 | 0.64 (0.46–0.89) | 62.5 | 0.67 (0.53–0.86) | 62.2 | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) | 50.9 | 0.54 (0.43–0.68) | 39.9 | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Prairie | 88.2 | 0.93 (0.52–1.65) | 60.9 | 0.65 (0.44–0.96) | 63.5 | 0.88 (0.60–1.29) | 50.7 | 0.56 (0.39–0.81) | 36.9 | 0.88 (0.59–1.31) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Alberta | 83.3 | 0.55 (0.35–0.88) | 59.8 | 0.57 (0.41–0.80) | 57.2 | 0.62 (0.44–0.86) | 45.7 | 0.42 (0.30–0.58) | 32.8 | 0.66 (0.47–0.93) |

|

| ||||||||||

| British Columbia | 86.9 | 0.72 (0.46–1.14) | 65.9 | 0.72 (0.52–1.00) | 69.3 | 1.14 (0.82–1.59) | 59.6 | 0.79 (0.57–1.08) | 41.7 | 0.99 (0.72–1.36) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Less than daily smoker | 87.1 | 1.00 | 75.0 | 1.00 | 72.9 | 1.00 | 63.1 | 1.00 | 42.7 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Daily smoker | 85.7 | 0.90 (0.63–1.28) | 61.0 | 0.53 (0.41–0.68) | 59.7 | 0.67 (0.51–0.86) | 51.7 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | 38.7 | 0.71 (0.55–0.91) |

|

| ||||||||||

| E-cigarette use status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Never tried | 87.1 | 1.00 | 66.0 | 1.00 | 72.0 | 1.00 | 61.8 | 1.00 | 49.6 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Tried but does not currently use | 85.8 | 0.89 (0.61–1.29) | 65.3 | 1.02 (0.77–1.34) | 57.1 | 0.52 (0.40–0.69) | 49.8 | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) | 38.4 | 0.68 (0.52–0.88) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Less than weekly user | 86.0 | 1.04 (0.75–1.44) | 64.1 | 0.86 (0.68–1.10) | 62.1 | 0.58 (0.45–0.74) | 51.8 | 0.66 (0.52–0.83) | 33.5 | 0.56 (0.44–0.70) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Weekly user | 79.7 | 0.64 (0.43–0.94) | 66.1 | 0.96 (0.70–1.30) | 48.7 | 0.35 (0.26–0.47) | 48.0 | 0.56 (0.41–0.75) | 25.7 | 0.36 (0.26–0.50) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Daily user | 86.9 | 1.04 (0.64–1.70) | 57.3 | 0.61 (0.43–0.87) | 4.50 | 0.29 (0.21–0.42) | 49.3 | 0.54 (0.37–0.77) | 30.5 | 0.42 (0.29–0.62) |

|

| ||||||||||

| No. of cigarettes per day | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ≤ 10 | 87.0 | 1.00 | 69.8 | 1.00 | 69.1 | 1.00 | 59.4 | 1.00 | 40.5 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 11–20 | 86.5 | 0.87 (0.61–1.23) | 61.9 | 0.88 (0.69–1.12) | 59.3 | 0.73 (0.58–0.93) | 52.8 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 39.2 | 0.92 (0.72–1.18) |

|

| ||||||||||

| 21–30 | 81.8 | 0.61 (0.39–0.93) | 51.5 | 0.59 (0.43–0.81) | 49.9 | 0.54 (0.39–0.74) | 40.3 | 0.50 (0.36–0.70) | 36.7 | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) |

|

| ||||||||||

| > 30 | 79.6 | 0.49 (0.22–1.08) | 56.2 | 0.80 (0.42–1.52) | 54.2 | 0.73 (0.38–1.41) | 50.8 | 0.85 (0.45–1.62) | 50.1 | 1.58 (0.86–2.90) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Plans to quit in next 6 mo | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| No | 83.6 | 1.00 | 57.0 | 1.00 | 58.7 | 1.00 | 48.6 | 1.00 | 30.3 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Yes | 87.0 | 1.40 (1.05–1.86) | 67.7 | 1.77 (1.44–2.19) | 65.1 | 1.57 (1.27–1.94) | 57.1 | 1.63 (1.33–2.01) | 43.3 | 2.12 (1.70–2.64) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Logistic regression models controlled for sex, age group, ethnicity, household income, education level, province/region, smoking status, e-cigarette use status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, plans to quit in next 6 months, perception of societal attitudes toward smoking and belief that smokers are increasingly marginalized.

Smokers with plans to quit in the next 6 months were more likely to support all 14 endgame policies than those who did not plan to quit in the next 6 months. Smoking status was a significant predictor of support for 12 endgame policies. Daily smokers were less likely than those who did not smoke daily to support the following cigarette policies: marketing ban, total ban in 10 years, plain packaging, reducing nicotine content, additive/flavouring ban, menthol ban, raising the legal age for purchase and restrictions on places for purchase. Daily smokers were also less likely to support e-cigarette/e-liquid policies to restrict nicotine content, and a ban on use in smoke-free places, product promotion and fruit/candy flavours.

There were significant differences in support for 10 endgame policies by province/region. For cigarette policies, support was generally higher among smokers in Quebec than among smokers in the other provinces/regions. Smokers in most provinces/regions were less likely than those in Quebec to support a marketing ban, plain packaging and reducing nicotine content. Compared to smokers in Quebec, smokers in Alberta and Ontario were less likely to support a total tobacco ban in 10 years and banning menthol; those in Alberta were less likely to support banning additives/flavourings; and those in the Prairie region and Alberta were less likely to support requiring retailers to sell alternative nicotine products. Among e-cigarette policies, compared to smokers in Quebec, smokers in Ontario, the Prairie region and Alberta were less likely to support restricting nicotine content; those in Alberta were less likely to support a ban on use in smoke-free places; and those in all regions/provinces except British Columbia were less likely to support a ban on product promotion.

Sex, ethnicity, e-cigarette use status, age, education, income and daily consumption were not significantly associated with support for most of the endgame policies.

Interpretation

This study provides policy-makers with clear evidence of support for many novel endgame strategies from current smokers, who would be most affected by the majority of these proposals. There was particularly strong support for measures to restrict youth access and to regulate nicotine content in cigarettes and e-cigarettes/e-liquid (64.9%–86.1%), followed by marketing bans for cigarettes (58.5%) and e-cigarettes (54.8%), and additive/flavouring bans for cigarettes/tobacco (42.5%) and e-cigarettes (39.8%). There was even considerable support (43.6%) for the most radical policy, to completely ban the sale of cigarettes/tobacco within 10 years if cessation support is provided, which is consistent with findings from other countries.35,36,43

Support was low for banning menthol, especially in contrast to support for reducing nicotine content in cigarettes (29.6% v. 70.2%). This pattern is consistent with previous studies37,44 and may be due to smokers’ misperceptions that menthol cigarettes are less harmful than regular cigarettes.45,46 Support for plain packaging (28.9%) was also lower than that for other measures. However, it was similar to that observed among smokers before plain packaging was implemented in Australia, where support rose from 28.2% to about 50% after implementation.39 At the time of this study, a national menthol ban in Canada was not yet in force, and plain packaging was under formal consideration. Previous research showing postimplementation increases in policy support47–49 suggests that smokers’ support for banning menthol and plain packaging should increase after these policies are implemented in Canada. It is unclear why support for many endgame measures was consistently highest in Quebec. Future studies on reasons for these provincial differences are warranted.

Smokers with plans to quit in the next 6 months were more likely to support all 14 endgame policies than those who did not plan to quit within this time frame. Together with the finding that close to half (44%) of smokers would support a total ban on the sale of cigarettes within 10 years if the government provided cessation assistance, the results show that many Canadian smokers have a strong desire to quit and want services to help them quit. These results are consistent with those of other studies showing that a high proportion of Canadian smokers regret having started smoking50 and that most are interested in quitting and plan to quit.51,52 Endgame proposals that include enhanced resources for cessation will likely lead to greater support.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the survey results are not representative of the Aboriginal population of Canada: Aboriginal Canadians represented less than 5% of the total sample. National census data indicate that about 4.2% of the Canadian population (around 1.4 million people) identifies as First Nations, Métis or Inuit.53 It is estimated that 40% of First Nations and Métis adults (age ≥ 18 yr) smoke more than twice the rate among the general Canadian population.54 Future studies are needed to assess support for endgame measures among Aboriginal groups. Second, our sample consisted only of smokers, even though nonsmokers constitute more than 85% of the Canadian population.3 Based on previous studies,55–57 it is likely that nonsmokers’ support for endgame policies is even greater than the levels reported by smokers in the current study. Finally, we did not assess smokers’ support for other key endgame proposals, such as tobacco retailer licensing systems, tobacco price caps, forced tobacco supply reduction and encouraging smokers to switch to or use e-cigarettes to quit.26,58–62

Conclusion

Our findings show that a majority of Canadian smokers support diverse tobacco endgame measures. Our baseline estimates suggest that innovative endgame strategies that go beyond current measures are likely to be well received by Canadians, including smokers, who stand to be most affected by new policies. As endgame policies are implemented in Canada, it will be important to study their impact on tobacco use, particularly among vulnerable populations such as Indigenous peoples and groups with low socioeconomic status.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Janine Ouimet, project manager of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Project at the time of the study, and Christian Boudreau and Mary Thompson from the International Tobacco Control Data Management Core team at the University of Waterloo for their assistance with compiling the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys. The authors also thank Genevieve Sansone from the University of Waterloo for creating the figure.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Geoffrey Fong is the chief principal investigator of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Project and contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study. Janet Chung-Hall drafted the manuscript and prepared the final version. Pete Driezen analyzed the data. Janet Chung-Hall and Pete Driezen contributed to the interpretation of data. Geoffrey Fong, Lorraine Craig and Pete Driezen revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey in the United States, Canada and England was supported by grant P01 CA200512 from the US National Cancer Institute and by Foundation Grant FDN-148477 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Additional support was provided to Geoffrey Fong from a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/3/E412/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N, et al. The tobacco atlas, fifth edition. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tobacco [fact sheet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [accessed 2017 May 10]. Available: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs (CTADS): 2015 summary. 2017. [accessed 2018 Sept 13]. modified 2017 June 27). Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2015-summary.html.

- 4.Rehm J, Baliunas D, Brochu S, et al. The cost of substance abuse in Canada 2002: highlights. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baliunas D, Patra J, Rehm J, et al. Smoking-attributable mortality and expected years of life lost in Canada 2002: conclusions for prevention and policy. Chronic Dis Can. 2007;27:154–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobrescu A, Bhandari A, Sutherland G, et al. The costs of tobacco use in Canada, 2012: highlights. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobacco Reporting Regulations (SOR/2000-273) Ottawa: Government of Canada [Justice Laws website]; 2000. [accessed 2017 May 15]. (updated 2018 Aug 19, amended 2018 May 23). Available: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2000-273/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Order amending the schedule of the Tobacco Act (menthol) [accessed 2017 Oct 18];Canada Gazette. 2017 151(7) Available: www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2017/2017-04-05/html/sor-dors45-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seizing the opportunity: the future of tobacco control in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2017. [accessed 2017 June 27]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/programs/future-tobacco-control/future-tobacco-control.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Schwartz R. The effect of tobacco control strategies and interventions on smoking prevalence and tobacco-attributable deaths in Ontario, Canada: technical report of the Ontario SimSmoke. Toronto: Ontario Tobacco Research Unit; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malone RE. Tobacco endgames: what they are and are not, issues for tobacco control strategic planning and a possible US scenario. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i42–4. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EA. Questions for a tobacco-free future. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i1–2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDaniel PA, Smith EA, Malone RE. The tobacco endgame: a qualitative review and synthesis. Tob Control. 2016;25:594–604. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobacco free Ireland: report of the Tobacco Policy Review Group. Dublin: Department of Health; 2013. [accessed 2017 May 10]. Available: http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TobaccoFreeIreland.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Government final response to report of the Māori Affairs Committee on inquiry into the tobacco industry in Aotearoa and the consequences of tobacco use for Māori (final response) Wellington (New Zealand): Parliament Buildings; 2011. [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. Available: https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-nz/49DBHOH_PAP21175_1/9f015010d386fe11050cddfbb468c2a3f5b0cb89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creating a tobacco-free generation: a tobacco control strategy for Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2013. [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. Available: www.gov.scot/Resource/0041/00417331.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roadmap to a tobacco-free Finland: action plan for tobacco control. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2014. [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. Available: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/70305/URN_ISBN_978-952-00-3513-6.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armes C. Media advisory — Queen’s University hosts summit on the creation of a tobacco endgame for Canada [news release] Kingston (ON): Queen’s University; 2016. [accessed 2017 Aug 29]. Available: www.queensu.ca/gazette/media/media-advisory-queens-university-hosts-summit-creation-tobacco-endgame-canada. [Google Scholar]

- 19.A tobacco endgame for Canada. Summit, Queen’s University, September 30 to October 1, 2016. Background paper. 2016. [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. Available: www.queensu.ca/gazette/sites/default/files/assets/attachments/EndgameSummit-Backgroundpaper.pdf.

- 20.Canada’s Tobacco Strategy. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2018. [accessed 2017 Aug 3]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/canada-tobacco-strategy/overview-canada-tobacco-strategy-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burstein P. The impact of public opinion on public policy: a review and an agenda. Polit Res Q. 2003;56:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petry F. The opinion–policy relationship in Canada. J Polit. 1999;61:540–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petry F, Mendelsohn M. Public opinion and policy making in Canada 1994–2001. Can J Polit Sci. 2004;37:505–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howlett M. Predictable and unpredictable policy windows: institutional and exogenous correlates of Canadian federal agenda-setting. Can J Polit Sci. 1998;31:495–524. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penner E, Blidook K, Soroka S. Legislative priorities and public opinion: representation of partisan agendas in the Canadian House of Commons. J Eur Public Policy. 2006;13:1006–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson G, Wilson N, Blakely T, et al. Ending appreciable tobacco use in a nation: using a sinking lid on supply. Tob Control. 2010;19:431–5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson N, Thomson GW, Edwards R, et al. Potential advantages and disadvantages of an endgame strategy: a “sinking lid” on tobacco supply. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i18–21. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashley MJ, Cohen JE. What the public thinks about the tobacco industry and its products. Tob Control. 2003;12:396–400. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashley MJ, Cohen J, Bull S, et al. Knowledge about tobacco and attitudes toward tobacco control: How different are smokers and nonsmokers? Can J Public Health. 2000;91:376–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03404811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii3–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control ITC Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii12–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey Wave 1 [technical report] Waterloo (ON): University of Waterloo; Charleston (SC): Medical University of South Carolina; Melbourne (Australia): Cancer Council Victoria; London (UK): King’s College London; 2017. [accessed 2018 Aug 3]. Available: https://www.itcproject.org/technical-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Methods. Waterloo (ON): Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo; [accessed 2017 May 15]. (updated 2013 May 7). Available: www.itcproject.org/methods. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahab L, West R. Public support in England for a total ban on the sale of tobacco products. Tob Control. 2010;19:143–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.033415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards R, Wilson N, Peace J, et al. Support for a tobacco endgame and increased regulation of the tobacco industry among New Zealand smokers: results from a national survey. Tob Control. 2013;22:e86–93. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fix BV, O’Connor RJ, Fong GT, et al. Smokers’ reactions to FDA regulation of tobacco products: findings from the 2009 ITC United States survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:941. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson N, Blakely T, Edwards R, et al. Support by New Zealand smokers for new types of smokefree areas: national survey data. N Z Med J. 2009;122:80–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swift E, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Australian smokers’ support for plain or standardised packs before and after implementation: findings from the ITC Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2015;24:616–21. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young D, Borland R, Siahpush M, et al. ITC Collaboration. Australian smokers support stronger regulatory controls on tobacco: findings from the ITC Four-Country Survey. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31:164–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bondy SJ, Victor JC, Diemert LM. Origin and use of the 100 cigarette criterion in tobacco surveys. Tob Control. 2009;18:317–23. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; [accessed 2017 May 17]. (modified 2017 Sept 27). Available: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/survey/household/4440. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connolly GN, Behm I, Healton CG, et al. Public attitudes regarding banning of cigarettes and regulation of nicotine. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e1–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolcic-Jankovic D, Biener L. Public opinion about FDA regulation of menthol and nicotine. Tob Control. 2015;24:e241–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King B, Yong HH, Borland R, et al. Malaysian and Thai smokers’ beliefs about the harmfulness of “light” and menthol cigarettes. Tob Control. 2010;19:444–50. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brennan E, Gibson L, Momjian A, et al. Are young people’s beliefs about menthol cigarettes associated with smoking-related intentions and behaviors? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:81–90. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, et al. Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland: findings from the ITC Ireland/UK Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii51–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagelhout GE, Mons U, Allwright S, et al. Prevalence and predictors of smoking in “smoke-free” bars. Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Europe surveys. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1643–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakefield MA, Hayes L, Durkin S, et al. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003175. e003175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fong GT, Hammond D, Laux FL, et al. The near-universal experience of regret among smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S341–51. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siahpush M, Yong HH, Borland R, et al. Smokers with financial stress are more likely to want to quit but less likely to try or succeed: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104:1382–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, et al. ITC Collaboration. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four Western countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(Suppl):S20–33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aboriginal peoples in Canada: First Nations, Métis and Inuit — National Household Survey, 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. Cat. no. 99-011-X2011001. Available: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS): smoking prevalence 1999 to 2012. Ottawa: Health Canada; [accessed 2017 Oct 18]. (modified 2013 Oct 1). Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-tobacco-use-monitoring-survey-smoking-prevalence-1999-2012.html. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lykke M, Pisinger C, Glümer C. Ready for a goodbye to tobacco? Assessment of support for endgame strategies on smoking among adults in a Danish regional health survey. Prev Med. 2016;83:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trainer E, Gall S, Smith A, et al. Public perceptions of the tobacco-free generation in Tasmania: adults and adolescents. Tob Control. 2017;26:458–60. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gendall P, Hoek J, Maubach N, et al. Public support for more action on smoking. N Z Med J. 2013;126:85–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chapman S. The case for a smoker’s license. PLoS Med. 2012;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001342. e1001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilmore AB, Branston JR, Sweanor D. The case for OFSMOKE: how tobacco price regulation is needed to promote the health of markets, government revenue and the public. Tob Control. 2010;19:423–30. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glynn TJ. E-cigarettes and the future of tobacco control. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:164–8. doi: 10.3322/caac.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeller M. Reflections on the ‘endgame’ for tobacco control. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i40–1. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levy DT, Cummings KM, Villanti AC, et al. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. Addiction. 2017;112:8–17. doi: 10.1111/add.13394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.