Abstract

Late-onset toxicity is common for novel molecularly targeted agents and immunotherapy. It causes major logistic difficulty for existing adaptive phase I trial designs, which require the observance of toxicity early enough to apply dose escalation rules for new patients. The same logistic difficulty arises when the accrual is rapid. We propose the time-to-event Bayesian optimal interval (TITE-BOIN) design to accelerate phase I trials by allowing for real-time dose assignment decisions for new patients while some enrolled patients’ toxicity data are still pending. Similar to the rolling six design, the TITE-BOIN dose escalation/de-escalation rule can be tabulated before the trial begins, making it transparent and simple to implement, but is more flexible in choosing the target DLT rate and has higher accuracy to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Compared to the more complicated model-based time-to-event continuous reassessment method (TITE-CRM), the TITE-BOIN has comparable accuracy to identify the MTD, but is simpler to implement with substantially better overdose control. As the TITE-CRM is more aggressive in dose escalation, it is less likely to underdose patients. When there is no pending data, the TITE-BOIN seamlessly reduces to the BOIN design. Numerical studies show that the TITE-BOIN design supports continuous accrual, without sacrificing patient safety nor the accuracy of identifying the MTD, and therefore has great potential to accelerate early phase drug development.

Introduction

The paradigm for phase I clinical trial design was initially established in the era of cytotoxic chemotherapies, for which toxicities were often acute and ascertainable in the first cycle of therapy. Over the past decade, non-cytotoxic therapies such as molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies have entered the clinic. Toxicity associated with these agents is often of late onset (1–3), as is that associated with conventional radiochemotherapy, which may occur several months post-treatment. To account for late-onset toxicity, it is imperative to use a relatively long toxicity assessment window (e.g., over multiple treatment cycles) to define the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) such that all DLTs relevant to the dose escalation and maximum tolerated dose (MTD) determination are captured. This, however, causes a major logistic difficulty when conducting phase I trials. For example, if the DLT takes up to 8 weeks to evaluate and the accrual rate is 1 patient/week, on average, five new patients will be accrued while waiting to evaluate the previous three patients’ outcomes. The question is: How can new patients receive timely treatment when the previous patients’ outcomes are pending?

The same difficulty arises with rapid accrual. Suppose that the DLT of a new agent can be assessed in the first 28-day cycle; if the accrual rate is 8 patients/28 days, then on average, five new patients will accrue while waiting to evaluate the previous three patients’ outcomes, and we must determine how to provide them with timely treatment. To quantify the severity of such logistic difficulty, Jin et al (4) defined the logistic difficulty index (LDI) = accrual rate × length of the DLT assessment window, where LDI ≤ 1 respresents no or minimal logistic difficulty as by the time a new patient is accrued, patients accrued previously are expected to complete their DLT assessment; and a larger value of LDI > 1 means increasingly severe logistic difficulty to determine a dose for new patients as more patients are expected to have their DLT data pending.

This logistic difficulty persists throughout the trial and cripples most existing novel adaptive designs, such as the continuous reassessment method (CRM) (5), escalation with overdose control (6), the modified toxicity probability interval (mTPI) design (7), Bayesian optimal interval (BOIN) design (8, 9) and the keyboard design (10). To make real-time decision of dose assignment, these designs require that the DLT is quickly ascertainable such that by the time of enrolling the next new cohort of patients, patients previously enrolled have completed their DLT assessment. If some of the enrolled patients’ DLT data are pending, these designs have difficulty informing a real-time decision of dose assignment for the new patients. One possible approach to circumvent this difficulty is to suspend accrual after each cohort and wait until the DLT data for the already accrued patients have cleared before enrolling the next new cohort. This approach of repeatedly interrupting accrual, however, is highly undesirable and often infeasible in practice. It delays treatment for new patients and slows down the trial.

Several phase I designs have been proposed to allow for continuous accrual and real-time dose assignment for new patients when some previous patients’ DLT data are still pending due to late-onset toxicity or rapid accrual. The rolling six (R6) design is a modification of the 3+3 design that allows for continuous accrual of up to six patients when some of the patients’ DLT data are pending (11). Specifically, given that 3 to 6 patients have been treated at the current dose, the R6 enumerates all possible outcomes (i.e., DLT/no DLT/pending) from these patients, and provides the corresponding decision rule of dose assignment for the new patients. For example, among 3 patients treated, if one has DLT, one has no DLT, and one has a pending outcome, the R6 assigns the next cohort to the same dose. The main advantage of the R6 is its transparency and simplicity. Implementing the R6 does not require complicated model fitting and estimation. Users only count the number of patients with DLTs, the number of patients without DLTs and the number of patients with pending outcomes, and then uses the decision table to determine the dose assignment for the next new cohort. However, as an algorithm-based design, the R6 inherits the drawbacks of the 3+3 design such as low accuracy for MTD identification, treating a large proportion of patients at low (potentially subtherapeutic) doses and inability to target a specific DLT rate for the MTD. The time-to-event CRM (TITE-CRM) is a model-based design that allows for continual accrual and dose escalation decisions while some patients’ DLT data are pending (12, 13). TITE-CRM assumes a parametric model for the dose–toxicity curve. After each cohort of patients are treated, TITE-CRM re-evaluates the curve by updating the estimates of the model parameters to guide the dose allocation for subsequent patients. TITE-CRM yields better operating characteristics than R6 (14, 15), but is more statistically and computationally complex, which limits its use.

We propose a novel time-to-event BOIN (TITE-BOIN) design, a model-assisted design (16, 17) that combines the simplicity of the algorithm-based R6 design with the good performance of the model-based TITE-CRM design. TITE-BOIN allows for continuous accrual while some patients’ DLT outcomes are pending. Similar to the R6 design, the TITE-BOIN dose escalation/de-escalation rule can be tabulated before the trial begins, making it simple to implement. However, TITE-BOIN is more efficient and flexible, yielding performance that is better than the R6 design and comparable to that of more complicated TITE-CRM.

Methods

TITE-BOIN

We first review the BOIN design, upon which the TITE-BOIN design is built. Let denote the observed DLT rate at the current dose, defined as , where is the number of patients who have experienced DLT at the current dose, and is the total number of patients treated at the current dose. The BOIN design determines dose escalation/de-escalation by comparing with a pair of fixed, predetermined values: dose escalation boundary λe and de-escalation boundary .

If , escalate the dose to the next higher level;

if , de-escalate the dose to the next lower level;

otherwise stay at the current dose.

The formulas for the optimal escalation and de-escalation boundaries λe and are provided in the Supplementary Appendix A. To illustrate, given the target DLT rate of 30%, the default escalation boundary is λe = 0.236 and the de-escalation boundary is λd = 0.358. Suppose that 3 patients have been treated at the current dose. If none had DLT, the observed DLT rate =0/3=0, which is less than λe = 0.236, thus the design escalates the dose. If 2 patients had DLT, the observed DLT rate =2/3=0.67, which is greater than λe = 0.358, thus the design de-escalates the dose. If 1 patient had DLT, the observed DLT rate =1/3=0.33, which is between λe = 0.236 and λe = 0.358, then the design retains the current dose. Although an extremely simple design, large-scale numerical studies show that BOIN has good performance that is comparable to that of the more complicated CRM design (16, 17). As noted by a referee, because by default the BOIN uses a non-informative prior (i.e., a priori the current dose is equally likely to be below, equal to or above the MTD), its decision rule has an appearance of the classical frequentist design and only involves the observed DLT rate, the maximum likelihood estimate of the true DLT rate at the current dose. Actually, the BOIN can also be derived as a frequentist design, and its decision rule is equivalent to using the likelihood ratio test to determine dose escalation/de-escalation (8). Having both Bayesian and frequentist interpretations is a strength of the BOIN, making it appealing to wider audiences. In contrast, the mTPI and keyboard designs only have a Bayesian interpretation and require specification of the prior and calculation of the posterior distribution.

Like most adaptive phase I designs, BOIN requires that the DLT is quickly ascertainable so that the decision rule can choose a dose for the next new patient. With late-onset toxicity or rapid accrual, BOIN faces the aforementioned logistic difficulty: When some patients’ DLT data are pending, the value of is unknown; therefore, cannot be calculated, and the dose escalation/de-escalation rule cannot be applied.

TITE-BOIN overcomes this difficulty by imputing the DLT outcome for patients whose DLT data are pending (hereafter denoted as “pending patients”). After the imputation, becomes known and can be calculated and compared with λe and to determine dose escalation/de-escalation. Imputation is a well-established statistical technique for handling missing data (18–20). One innovation of our imputation method is to utilize data from all patients, including DLT data from patients who have completed DLT assessment and follow-up time data from the pending patients. As first noted by Cheung and Chappell (12) in TITE-CRM, the follow-up data for a pending patient contain rich information as to the likelihood that the patient will experience DLT. For example, a pending patient who is 3 days away from completing DLT assessment is less likely to experience DLT than a pending patient who has been followed for only 3 days, as the latter has a higher chance of experiencing DLT during the remaining follow-up time. The use of the pending patients’ follow-up time distinguishes TITE-BOIN from the R6 design and renders it higher accuracy to identify the MTD (see Numerical Study). We define the total follow-up time (TFT) as the sum of the follow-up times for all currently pending patients at the current dose, and standardized TFT (STFT) as the TFT divided by the length of DLT assessment window. For example, given that the DLT assessment window is 3 months and, at the current dose, 3 pending patients have been respectively followed 1, 1.6 and 2.5 months, the TFT is 1+1.6+2.5 = 5.1 months, and STFT = TFT/3 = 1.7. The technical details of imputing the DLT outcomes for patients with pending DLTs are provided in the Supplementary Appendix A. As shown later, by using the STFT, TITE-BOIN yields accuracy for identifying the MTD that is comparable to that for TITE-CRM, which also uses the follow-up time to make decisions of dose escalation/de-escalation.

TITE-BOIN, however, is more transparent and straightforward to implement than TITE-CRM, which requires repeated, complicated model fitting after treating each patient. The dose escalation/de-escalation rule of TITE-BOIN can be tabulated prior to trial conduct in a way similar to that of the R6 design. Table 1 shows the TITE-BOIN decision rule with a cohort size of 3 and the target DLT rate of 0.2, and Supplementary Table S1 provides the decision rule for the target DLT rate of 0.3. During the trial, at the current dose, we count the number of patients, the number of patients who experienced DLT, and the number of pending patients and their STFT, and then use the table to make the dose escalation/de-escalation decision. Suppose that 3 patients have been treated at the current dose, and one of them had DLT. We de-escalate the dose regardless of the STFT. Consider another case where 9 patients have been cumulatively treated at the current dose and 1 patient had DLT and 4 patients have DLT data pending. To treat the next cohort, if the STFT of the 4 pending patients is greater than 2.15, we escalate the dose; otherwise we retain the current dose. Table 1 assumes a cohort size of 3, but our method allows any prespecified cohort size, and the corresponding decision table (i.e., similar to Table 1 but with more rows) can be easily generated using the software described later. The TITE-BOIN design is described in Table 2.

Table 1.

Dose escalation and de-escalation rule for TITE-BOIN with a target DLT rate of 0.2 and a cohort size of 3.

| No. treated | No. DLTs | No. data pending | STFT

|

No. treated | No. DLTs | No. data pending | STFT

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escalate | Stay | De-escalate | Escalate | Stay | De-escalate | ||||||

| 3 | 0 | ≤1 | Y | 12 | 1 | 6 | ≥1.24 | <1.24 | |||

| 3 | 0 | ≥2 | Suspend accrual | 12 | 1 | ≥7 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 3 | 1 | ≤2 | Y | 12 | 2 | ≤6 | Y | ||||

| 3 | ≥2 | ≤1 | Y&Elim | 12 | 2 | ≥7 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 6 | 0 | ≤3 | Y | 12 | 3, 4 | ≤9 | Y | ||||

| 6 | 0 | ≥4 | Suspend accrual | 12 | ≥5 | ≤7 | Y&Elim | ||||

| 6 | 1 | ≤3 | Y | 15 | 0 | ≤7 | Y | ||||

| 6 | 1 | ≥4 | Suspend accrual | 15 | 0 | ≥8 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 6 | 2 | ≤4 | Y | 15 | 1 | ≤7 | Y | ||||

| 6 | ≥3 | ≤3 | Y&Elim | 15 | 1 | ≥8 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 9 | 0 | ≤4 | Y | 15 | 2 | ≤2 | Y | ||||

| 9 | 0 | ≥5 | Suspend accrual | 15 | 2 | 3 | ≥1.14 | <1.14 | |||

| 9 | 1 | ≤2 | Y | 15 | 2 | 4 | ≥2.31 | <2.31 | |||

| 9 | 1 | 3 | ≥0.77 | <0.77 | 15 | 2 | 5 | ≥3.48 | <3.48 | ||

| 9 | 1 | 4 | ≥2.15 | <2.15 | 15 | 2 | 6 | ≥4.65 | <4.65 | ||

| 9 | 1 | ≥5 | Suspend accrual | 15 | 2 | 7 | ≥5.82 | <5.82 | |||

| 9 | 2 | 0 | Y | 15 | 2 | ≥8 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 9 | 2 | 1 | >0.52 | ≤0.52 | 15 | 3 | ≤2 | Y | |||

| 9 | 2 | 2 | >1.59 | ≤1.59 | 15 | 3 | 3 | >1.16 | ≤1.16 | ||

| 9 | 2 | 3 | >2.66 | ≤2.66 | 15 | 3 | 4 | >2.34 | ≤2.34 | ||

| 9 | 2 | 4 | >3.73 | ≤3.73 | 15 | 3 | 5 | >3.53 | ≤3.53 | ||

| 9 | 2 | ≥5 | Suspend accrual | 15 | 3 | 6 | >4.72 | ≤4.72 | |||

| 9 | 3 | ≤6 | Y | 15 | 3 | 7 | >5.90 | ≤5.90 | |||

| 9 | ≥4 | ≤5 | Y&Elim | 15 | 3 | ≥8 | Suspend accrual | ||||

| 12 | 0 | ≤6 | Y | 15 | 4, 5 | ≤11 | Y | ||||

| 12 | 0 | ≥7 | Suspend accrual | 15 | ≥6 | ≤9 | Y&Elim | ||||

| 12 | 1 | ≤5 | Y | ||||||||

Note: “No. treated” is the total number of patients treated at the current dose level, “No. DLTs” is the number of patients who experienced DLT at the current dose level, “No. with data pending” denotes that number of patients whose DLT data are pending at the current dose level, “STFT” is the standardized total follow-up time for the patients with data pending, defined as the total follow-up time for the patients with data pending divided by the length of the DLT assessment window. “Y” represents “Yes”, and “Y&Elim” represents “Yes & Eliminate”. When a dose is eliminated, all higher doses should also be eliminated.

Table 2.

TITE-BOIN design

|

One remarkable feature of the TITE-BOIN is that its decision rule is invariant to the length of the assessment window, partially because the STFT has been standardized by the latter. This means that given a target DLT rate, the same decision table can be used to guide dose escalation and de-escalation, regardless of the length of the assessment window. For example, Table 1 can be used for any trial with the target DLT rate = 0.2, regardless of its assessment window. This is practically appealing and greatly simplifies trial protocol preparation because in practice what often varies across trials is the assessment window, while the target DLT rate is often 0.2, 0.25 or 0.3. Another attractive feature of the TITE-BOIN is that when there is no pending DLT data, it reduces to the BOIN design in a seamless way.

In principle, TITE-BOIN supports continuous accrual and allows for real-time dose assignment whenever a new patient arrives. To avoid risky decisions caused by sparse data, we impose an accrual suspension rule: If at the current dose, more than 50% of the patients’ DLT outcomes are pending, suspend the accrual to wait for more data to become available. This rule corresponds to “Suspend accrual” in Table 1. In practice, we also apply an overdose control rule: If the observed data suggest a high posterior probability (e.g., 95%) that the current dose is higher than the MTD, eliminate that and higher doses from the trial; and terminate the trial early if the lowest dose is eliminated (See the Supplementary Appendix A for statistical definition of this rule). This overdose control rule corresponds to the decision “Y&Elim”, representing “Yes & Eliminate”, under the column entitled “De-escalate” in Table 1.

Compared to R6 design, besides providing higher accuracy to identify the MTD, TITE-BOIN is also more flexible and can target any prespecified DLT rate. In contrast, the R6 design has no target DLT rate and tends to find a dose with DLT rate ranging from 17% to 26%. Such flexibility is of great clinical use. For example, for patients with recurrent cancer, a higher target DLT rate such as 30% may be an acceptable trade-off to achieve higher treatment efficacy; whereas for patients with cancer that has an effective treatment, a lower target DLT rate such as 20% may be more appropriate.

The sample size under TITE-BOIN (and also TITE-CRM) is prespecified, which allows clinicians to choose sample sizes to achieve the desirable probability of correct MTD estimation. In contrast, the R6 design imparts a restriction that the number of patients treated at any dose cannot exceed 6, which provides too little information to reliably estimate the true toxicity rate (see Numerical Study) and precludes the possibility of calibrating the sample size to obtain good operating characteristics. For example, if 1 of 6 patients experiences DLT, the estimated toxicity rate, 1/6 = 16.7%, seems low, but the 95% confidence interval (CI) for that estimate is (0.004, 0.641), indicating that the true toxicity rate can be as high as 64.1%. Conversely, if 3 of 6 patients experience DLT, the estimated toxicity rate, 3/6 = 50%, seems high, but the 95% CI for that estimate is (0.118, 0.88); and the true toxicity rate can be as low as 11.8%. The TITE-BOIN requires specification of the sample size, but it does not necessarily mean that the trial always has to reach that sample size. For example, if the lowest dose is overly toxic, the TITE-BOIN will terminate the trial early for patient safety. Additional stopping rules can be added to stop the trial early when there is adequate evidence that the MTD has been reached, for example, when the dose-finding algorithm continues to assign a large number of patients (e.g., 12 patients) to a dose, i.e., the dose-finding algorithm converges. Our TITE-BOIN software has incorporated this stopping rule to allow the sample size to adapt to emerging data. Table 3 summarizes some major differences between TITE-BOIN, R6 and TITE-CRM.

Table 3.

Comparison of design characteristics among R6, TITE-CRM and TITE-BOIN.

| Design characteristics | R6 | TITE-CRM | TITE-BOIN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Can it target any prespecified DLT rate? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Allows to use a cohort size other than 3? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Uses follow-up time data from pending patients to make efficient decision of dose escalation and de-escalation? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Can sample size be calibrated to ensure good operating characteristics? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Can the number of patients treated at the MTD be more than 6? | No | Yes | Yes |

| Can dose escalation/de-escalation rule be pre-tabulated for simple implementation? | Yes | No | Yes |

| Requires complicated, repeated estimation of the dose-toxicity curve model? | No | Yes | No |

Software

To facilitate the use of TITE-BOIN, we have developed graphical user interface-based software that allows users to generate the dose escalation and de-escalation table, conduct simulations, obtain the operating characteristics of the design, and generate a trial design template for protocol preparation. The software is freely available at the MD Anderson Software Download website (22) and at http://www.trialdesign.org.

Trial Example

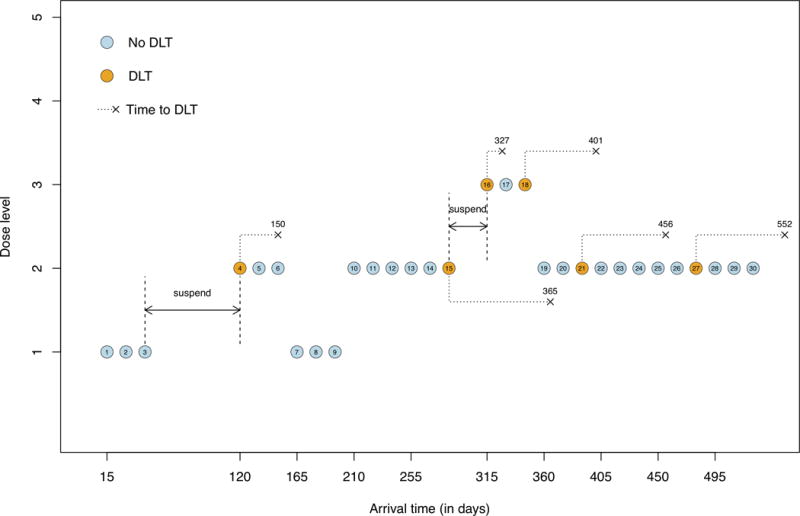

To illustrate TITE-BOIN, consider a phase I trial with the target DLT rate of 0.2 and five dose levels. The DLT assessment window is 3 months and the accrual rate is 2 patients/month. The total sample size is 30 patients, treated in cohorts of 3. Figure 1 shows the trial conduct using TITE-BOIN. The trial starts by treating the first cohort at the lowest dose level. By day 60, no DLT has been observed, and all three patients at the current dose have data pending. According to Table 1, accrual is suspended until the first two patients finish the assessment period (at day 120) without experiencing DLT. Following the TITE-BOIN rule, the second cohort is treated at dose level 2. By the arrival of patient 7 (day 165), one DLT is observed for patient 4, while patients 5 and 6 have finished only 1/3 and 1/6 of their follow-up without experiencing DLT. Thus, the dose level is de-escalated to dose 1 for patients 7 through 9. By day 210, 3 patients among the 6 patients at dose 1 have finished the assessment with no DLT observed, and the dose returns to level 2 for the fourth cohort. When patient 13 arrives on day 255, one of the 6 patients at dose 2 has experienced DLT, thus patients 13 through 15 are treated at dose level 2. By day 300, 9 patients have been treated at dose level 2, with only one DLT observed and 5 pending patients. The trial is suspended for 15 days to wait for more DLT data cleared. On day 315, patients 3 through 6 and patients 10 and 11 have finished the follow-up, while patients 12 through 15 have been followed for 75, 60, 45 and 30 days, respectively, and STFT = (75+60+45+30)/90 = 2.33, which is greater than the dose escalation boundary of 2.15. Patients 16 through 18 are thus treated at dose level 3. Since one DLT has been observed at dose level 3 before the arrival of patient 19, TITE-BOIN suggests de-escalating the dose to level 2. At the end of the trial, dose 2 is selected as the MTD, at which 4 of 21 patients had DLTs, with an estimated DLT rate of 0.19. It takes about 615 days (20.5 months) to finish the whole trial. By contrast, the trial would run about 1200 days (40 months) if we applied standard adaptive designs that require full DLT assessment before enrolling each new cohort.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical phase I clinical trial using the TITE-BOIN design. Patients are treated in cohort sizes of 3, and the number above the “×” indicates the time when DLT occurs.

Numerical Study

Simulation configuration

We used computer simulations to compare the TITE-BOIN, 3+3 design, R6 design, and TITE-CRM. We considered a phase I trial with 7 dose levels. The DLT assessment window is 3 months, the accrual rate is 2 patients/month, and patients are treated in cohorts of 3. On average, 6 new patients accrue during the DLT assessment window of the most recently treated patients. We considered the target DLT rate = 0.2 or 0.3, with 8 representative scenarios for each rate, resulting in 16 scenarios, which are constructed by augmenting 4 previously published scenarios (12), i.e., scenarios 3, 4, 5 and 7, with 12 additional scenarios to cover various MTD locations and dose-response curve shapes (see Supplementary Table S2). The time to DLT is sampled from a Weibull distribution, with 50% of DLTs occurring in the second half of the assessment window. The maximum sample size is 36 patients. Because the 3+3 and R6 designs often stopped the trial early (e.g., when 2 of 3 patients experienced DLT) before reaching 36 patients, in these cases, the remaining patients are treated at the selected “MTD” as the cohort expansion, such that the four designs have comparable sample sizes. For the 3+3 design and cohort expansion, a new cohort is enrolled only when the previous cohort’s DLT data are cleared. (See the Supplementary Appendix B for data generation and design settings.) Although we do not directly simulate a case of a short assessment window (e.g., 1 month) and with a fast accrual (e.g., 6 patients/month), the simulation results here are directly applicable to that case because they are equivalent with the same LDI after rescaling the time.

Performance metrics

We considered seven performance metrics based on 10,000 simulated trials.

Percentage of correct selection (PCS) of the MTD

Percentage of patients allocated to the MTD

Percentage of overdosing selection (i.e., selecting a dose above the MTD)

Percentage of patients overdosed (i.e., treated at doses above the MTD)

Percentage of patients underdosed (i.e., treated at doses below the MTD)

Percentage of “regretful” trials that failed to de-escalate the dose when 2 out of the first 3 patients had DLTs at any dose.

Average trial duration

Metrics 1 and 2 measure the accuracy of identifying the MTD and allocating patients; metrics 3 and 4 measure safety; metric 5 measures the likelihood of treating patients with potentially subtherapeutic doses. Because R6, TITE-CRM and TITE-BOIN allow for real-time dose assignment with pending data, some decisions may turn out to be regretful (or not sensible) after the pending data are observed, e.g., failure to de-escalate the dose when 2/3 patients had DLTs. Metric 6 is used to measure the frequency of such “regretful” trials. For ease of displaying the results, hereafter, we report the relative performance of each design against the performance of the 3+3 design. For example, the PCS of the R6 design is calculated as (PCS of the R6 design – PCS of the 3+3 design), and the other metrics are similarly calculated.

Results

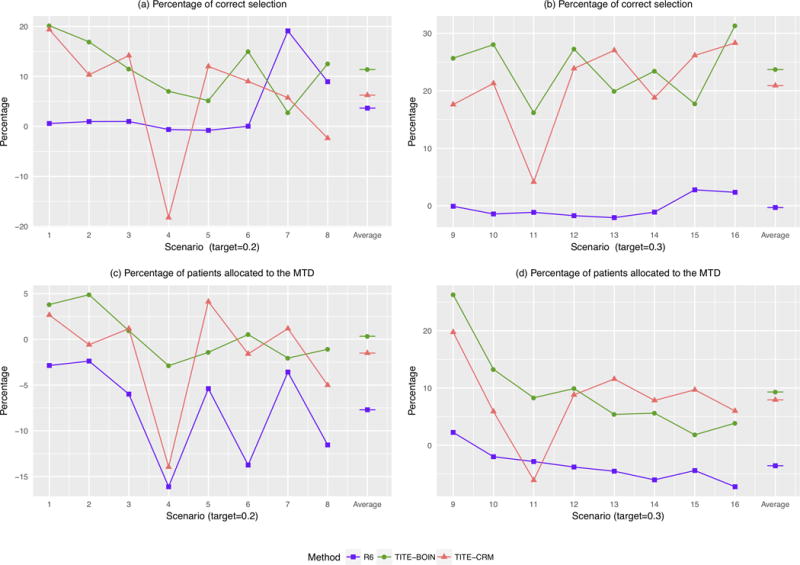

Accuracy of identifying and allocating patients to the MTD

Figure 2 provides the PCS of the MTD and the percentage of patients allocated to the MTD under the R6, TITE-CRM and TITE-BOIN designs, with respect to the 3+3 design. The R6 design performs similarly to the 3+3 design, with generally less than 5% difference. TITE-BOIN and TITE-CRM are comparable and outperform the R6 and 3+3 designs. Compared to the R6 and 3+3 designs, on average, TITE-BOIN has over 15% higher chance of correctly selecting the MTD, and allocates 5% more patients to the MTD.

Figure 2.

Comparative performances of the time-to-event Bayesian optimal interval (TITE-BOIN), rolling six (R6), and time-to-event continual reassessment method (TITE-CRM) designs with respect to that of the 3+3 design. (a and b) Relative percentages of correct selection (PCS) of the MTD; (c and d) Relative percentages of patients assigned to the MTD. The target DLT rate in scenarios 1-8 is 0.2, while that in scenarios 9-16 is 0.3. The accrual rate is 2 patients/month. A higher value is better.

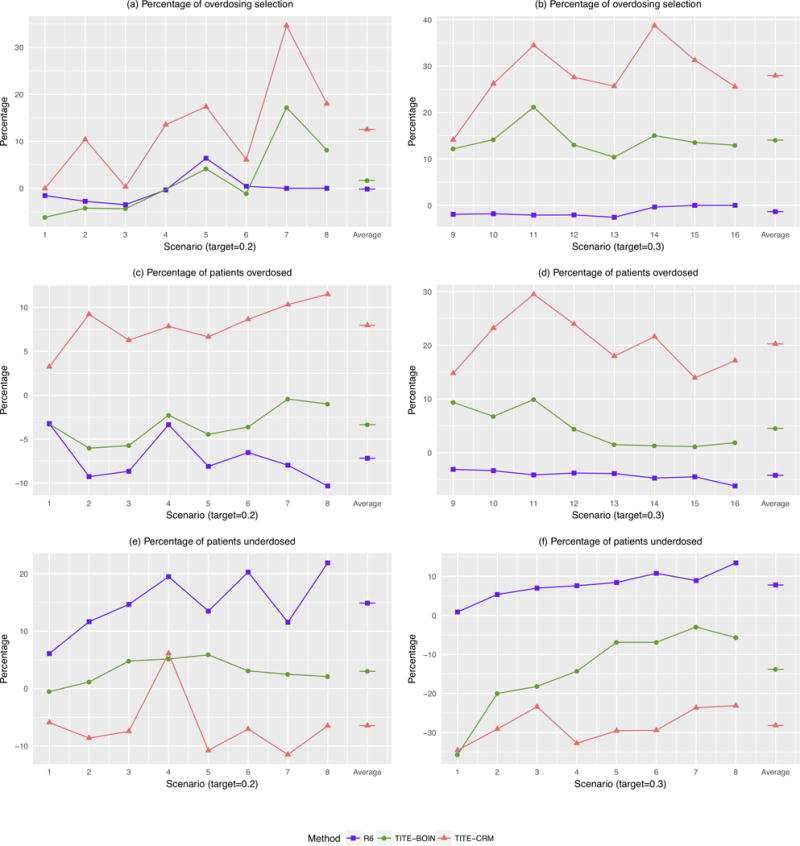

Overdose Control and Underdose Control

Figure 3 shows the percentage of overdosing selection, the percentage of patients overdosed, and the percentage of patients underdosed. The R6 design performs similarly to the 3+3 design and has lower risk of overdosing patients (Figure 3 (c) and (d)), but substantially higher risk of underdosing patients (Figure 3 (e) and (f)) than the TITE-BOIN and TITE-CRM designs. The difference between R6 and TITE-BOIN and TITE-CRM is larger under scenarios 9-16 because the R6 design finds a dose with the DLT rate around 20%, which is lower than the target DLT rate of 30%. This is consistent with previous findings that the 3+3 and R6 designs are overly conservative (4–7). Although being safe is desirable, being overly conservative results in poor precision for identifying the MTD (Figure 2) and treating a large percentage of patients at potentially subtherapeutic doses. TITE-BOIN shows good balance between safety (risk of overdosing) and correct identification of the MTD. Compared to the 3+3 and R6 designs, TITE-BOIN has much higher accuracy in identifying the MTD (Figure 2). Compared to TITE-CRM, the TITE-BOIN design has similar accuracy in identifying the MTD, but substantially lower risk of selecting overly toxic doses as the MTD and overdosing patients, especially when the target DLT rate is 0.3. As the TITE-CRM is more aggressive, it is less likely to underdose patients than the TITE-BOIN.

Figure 3.

Comparative performances of the time-to-event Bayesian optimal interval (TITE-BOIN), rolling six (R6), and time-to-event continual reassessment method (TITE-CRM) designs with respect to that of the 3+3 design. (a and b) Relative percentages of trials selecting the dose above the MTD; (c and d) Relative percentages of patients assigned to the doses above the MTD; (e and f) Relative percentages of patients assigned to doses below the MTD. The target DLT rate in scenarios 1-8 is 0.2, while that in scenarios 9-16 is 0.3. The accrual rate is 2 patients/month. A lower value is better.

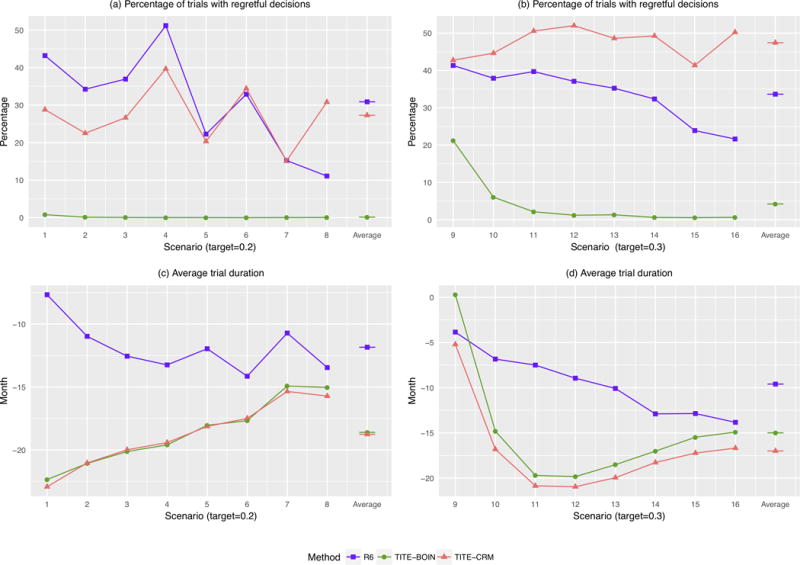

Regretful Trials

Figure 4 (a) and (b) shows the percentage of “regretful” trials. The 3+3 design does not allow for pending data, thus it never has regretful trials that fail to de-escalate when 2/3 patients had DLT, but at the cost of longer trial durations. The percentage of “regretful” trials under the TITE-BOIN is mostly 0, except when the first dose is the target (i.e., scenarios 9 and 10), which is much lower than those under the R6 and TITE-CRM.

Figure 4.

Comparative performances of the time-to-event Bayesian optimal interval (TITE-BOIN), rolling six (R6), and time-to-event continual reassessment method (TITE-CRM) designs with respect to that of the 3+3 design. (a and b) Relative percentages of “regretful” trials; (c and d) Average trial durations in months. The target DLT rate in scenarios 1-8 is 0.2, while that in scenarios 9-16 is 0.3. The accrual rate is 2 patients/month. A lower value is better.

Trial Duration

Figure 4 (c) and (d) shows the average trial duration. When the target DLT rate is 0.2, the average trial durations for TITE-CRM and TITE-BOIN are about 19 months shorter than the duration of the 3+3 design, and about 7 months shorter than that of the R6 design. When the target DLT rate is 0.3 and the MTD lies in the lowest dose level (scenarios 9), R6 (as well as the 3+3 design) tends to erroneously stop the trial early, which artificially shortens the trial.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted additional simulations to examine the robustness of TITE-BOIN in terms of the time-to-toxicity distribution and accrual rate (see Supplementary Appendix C). The results (see Supplementary Figures S1-S9) show that TITE-BOIN is robust and yields desirable operating characteristics under various scenarios. To confirm that our comparison results based on the 16 dose–toxicity scenarios are generally applicable, we conducted a much larger scale simulation study that compared the performance of the designs based on 50,000 randomly generated dose–toxicity scenarios with 10,000 simulated trials under each scenario (see Supplementary Appendix C and Supplementary Figure S10). The results (see Supplementary Table S3) are consistent with those reported above.

Discussion

The TITE-BOIN design provides an easy-to-implement and well-performing solution for phase I trials with late-onset toxicity or fast accrual. Like the R6 design, TITE-BOIN can be implemented in a simple way, but is more flexible in choosing the target DLT rate and has higher accuracy to identify the MTD. Actually, one major drawback of the R6 design is that it cannot target a specific DLT rate for the MTD. Compared to the more complicated model-based TITE-CRM, the TITE-BOIN has similar accuracy to identify the MTD, but has better overdose control and is simpler to implement. As the TITE-CRM is more aggressive in dose escalation, it is less likely to underdose patients. The TITE-BOIN design supports continuous accrual, without sacrificing patient safety nor the accuracy of identifying the MTD, thus provides a practical phase I design to accelerate early phase drug development. Moreover, when all the pending DLT data become available, the TITE-BOIN reduces to the BOIN design seamlessly.

TITE-BOIN uses only the “local” data at the current dose to make decisions of dose escalation and de-escalation. One may worry about potential efficiency loss from ignoring the data from the other doses. In contrast, TITE-CRM uses data from all doses through imposing a dose-toxicity curve model. As the assumed model is more likely to be misspecified than correctly specified in practice and also dose escalation is a sequential process that has automatically considered the toxicity order among the doses, large-scale numerical studies show negligible efficiency loss on average due to the use of only local data (16, 17). This phenomenon is also observed here, where the accuracy of identifying the MTD is similar between TITE-BOIN and TITE-CRM.

TITE-BOIN takes a non-informative approach and assumes that a priori the time to DLT is uniformly distributed over the assessment window, similar to TITE-CRM. Sensitivity analysis shows that the TITE-BOIN is very robust to this uniform assumption, which was also observed previously in the TITE-CRM. Thus, we recommend the uniform time-to-DLT prior as the default setting for general use, especially when there is limited prior knowledge on the toxicity profile of the investigational agent, e.g., a totally novel or first-in-human agent. Nevertheless, if reliable prior information is available on the distribution of the time to DLT, e.g., for the “me-too” or same-family drugs with a better known toxicity profile, an informative prior can be used to improve the design efficiency. For example, if we expect that the DLT is more likely to occur in the later part of the assessment window, we can use a prior distribution with more weights on the later part of the assessment window to incorporate that prior information. The details are provided in Supplementary Appendix D. Remarkably, using an informative prior for the time to DLT does not alter the decision table, e.g., the same table as Table 1 can be used for target DLT probability of 0.2, and we only need to weigh STFT accordingly and use the resulting weighted STFT (WSTFT) for decision making.

The design parameters should be calibrated to fit specific design requirements. For example, the TITE-BOIN suspends the accrual when the number of pending patients is more than half the total. If there is strong prior information that the investigational drug is relatively safe, we may use a smaller cutoff to decrease the chance of suspending accrual and speed up the trial. Conversely, if there is strong prior information that the investigational drug may be toxic, we may use a larger cutoff, such as three quarters of the sample size, to perform more conservative dose escalation at the cost of prolonging the trial duration. The same principle is applicable to the TITE-CRM. For example, a more stringent accrual pending rule or overdose control rule can be used to decrease the risk of overdosing for the TITE-CRM.

This paper focuses on making real-time dose assignments for new patients when some existing patients’ DLT data are still pending due to late-onset toxicity or fast accrual. A closely related question is how to account for toxicity in the decision making of dose escalation and MTD selection if some drug-related toxicity unexpectedly occurs outside of the assessment window, i.e., the toxicity onset is later than anticipated. A preferable approach is to prospectively and carefully choose an appropriate DLT assessment window such that it will capture all drug-related toxicity that is relevant to the MTD determination. For example, if we suspect that the onset of DLT may be quite late, we should choose a long assessment window. In the case that the prespecified assessment window fails to cover some toxicities, we could retrospectively expand the DLT assessment window based on the emerging data such that it covers these relevant toxicities. Such an approach is less desirable because it involves re-defining the time frame for the DLT assessment and requires a major protocol amendment. This article focuses on single-agent trials. TITE-BOIN can be extended to handle drug combination trials along the same line as the BOIN combination design (23). Another topic of interest for our future research is to extend other model-assisted designs (16, 17), such as the keyboard and mTPI designs, to handle late-onset toxicity and fast accrual.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and three reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent FDA’s views or policies.

Grant Support: YY’s research is partially supported by National Cancer Institute award P50CA098258.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclaimers: Ying Yuan is a consultant of Juno Therapeutics.

The study has not been presented elsewhere.

References

- 1.Postel-Vinay S, Gomez-Roca C, Molife LR, Anghan B, Levy A, Judson I, et al. Phase I trials of molecularly targeted agents: should we pay more attention to late toxicities? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1728–1735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.June CH, Warshauer JT, Bluestone JA. Is autoimmunity the Achilles’ heel of cancer immunotherapy? Nat Med. 2017;23:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nm.4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber JS, Yang JC, Atkins MB, Disis ML. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2092–2099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin I, Liu S, Thall PF, Yuan Y. Using data augmentation to facilitate conduct of phase I-II clinical trials with delayed outcomes. J Am Stat Assoc. 2014;109:525–536. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2014.881740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Quigley J, Pepe M, Fisher L. Continual reassessment method: a practical design for phase I clinical trials in cancer. Biometrics. 1990;46:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babb J, Rogatko A, Zacks S. Cancer phase I clinical trials: efficient dose escalation with overdose control. Stat Med. 1998;17:1103–1120. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980530)17:10<1103::aid-sim793>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji Y, Liu P, Li Y, Bekele BN. A modified toxicity probability interval method for dose-finding trials. Clin Trials. 2010;7:653–663. doi: 10.1177/1740774510382799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu S, Yuan Y. Bayesian optimal interval designs for phase I clinical trials. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 2015;64:507–523. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan Y, Hess KR, Hilsenbeck SG, Gilbert MR. Bayesian optimal interval design: a simple and well-performing design for phase I oncology trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4291–4301. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan F, Mandrekar SJ, Yuan Y. Keyboard: A novel Bayesian toxicity probability interval design for phase I clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3994–4003. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skolnik JM, Barrett JS, Jayaraman B, Patel D, Adamson PC. Shortening the timeline of pediatric phase I trials: the rolling six design. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:190–195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung YK, Chappell R. Sequential designs for phase I clinical trials with late-onset toxicities. Biometrics. 2000;56:1177–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normolle D, Lawrence T. Designing dose-escalation trials with late-onset toxicities using the time-to-event continual reassessment method. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4426–4433. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao L, Lee J, Mody R, Braun TM. The superiority of the time-to-event continual reassessment method to the rolling six design in pediatric oncology Phase I trials. Clin Trials. 2011;8:361–369. doi: 10.1177/1740774511407533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doussau A, Geoerger B, Jiménez I, Paoletti X. Innovations for phase I dose-finding designs in pediatric oncology clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou H, Murray T, Pan H, Yuan Y. Comparative review of novel model-assisted designs for phase I clinical trials. Stat Med. 2018 doi: 10.1002/sim.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou H, Yuan Y, Nie L. Accruracy, safety and reliability of novel phase I trial designs. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Research Council. The Prevention and Treatment of Missing Data in Clinical Trials. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little RJ, D’agostino R, Cohen ML, Dickersin K, Emerson SS, Farrar JT, et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barlow RE, Bartholomew DJ, Bremner JM, Brunk HD. Statistical inference under order restrictions. London: Wiley; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.BOIN design desktop program, MD Anderson Cancer Center Software Download Kiosk. 2017 https://biostatistics.mdanderson.org/softwaredownload/SingleSoftware.aspx?Software_Id=99.

- 23.Lin R, Yin G. Bayesian optimal interval designs for dose finding in Drug-combination trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017;26:2155–2167. doi: 10.1177/0962280215594494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.