Abstract

Background:

Fractures of the hook of hamate in baseball players are significant injuries that can lead to pain and missed time from competition. The diagnosis is typically delayed because of the vagueness of symptoms and normal radiographic findings. Excision of the nonunited fragment has been supported as the primary treatment, but there are currently limited information and data on a timetable for return to competition after surgery.

Purpose:

To report on a large cohort of competitive baseball players with hook of hamate fractures treated with excision of the fragment and to assess the timetable for return to full athletic competition.

Study Design:

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

Competitive baseball players treated between 2012 and 2017 with hook of hamate excision for acute fractures or chronic fracture nonunions were retrospectively identified. All patients were treated by the same surgeon, and the time to return to full athletic competition was assessed. Return to play was defined as reaching the athlete’s preinjury level and being able to perform full sport activities.

Results:

A total of 41 baseball players were identified, all of whom were documented to have a chronic presentation of a nonunion or partial union. The population consisted completely of male athletes, with a median age of 21 years (range, 18-34 years). All patients were competitive athletes, with 12 professional baseball players, 17 collegiate baseball players, and 12 high school baseball players. All patients were treated with hook of hamate excision, with 7 patients undergoing concomitant procedures as indicated. The median time to return to play was 5 weeks (range, 3-7 weeks). The time to return to play was similar between professional, collegiate, and high school athletes. All athletes returned to their preinjury level of activity by 7 weeks postoperatively.

Conclusion:

This study confirms that excision of the fractured hook provides predictable, early return to play, with a limited complication rate.

Keywords: hook of hamate, fracture, return to play, baseball

Fractures of the hook of hamate are injuries among patients who play baseball, golf, and racquet sports, occurring in 2% to 4% of all carpal fractures in athletes.21 These injuries can be secondary to acute trauma or can be the result of repetitive microtrauma of a bat, club, or racquet against the hook of hamate during contact.20 Although some of these injuries may present as acute ulnar-sided wrist pain after an inciting event, many of these cases present as chronic, vague, worsening ulnar-sided wrist pain with no identifiable trauma. The diagnosis of a chronic hook of hamate fracture can be difficult to make because of the vagueness of the symptoms and the fracture often not being visualized on standard radiographs.2 The proper diagnosis and treatment of these injuries are important, as a hook of hamate fracture can impinge on the ulnar nerve or the flexor tendons to the ring and small fingers, potentially leading to motor or sensory deficits as well as ruptures of the flexor tendons.2,13,16

The previous literature indicates that open excision of these injuries is superior to open reduction internal fixation (ORIF), as the limited vascular supply to the watershed area of the hook body can lead to nonunions and further complications.16 Over the past 20 years, there have been several studies that have reported on the results of hook of hamate excision in competitive athletes.2,4,6,14,20,23,24 These studies, however, consisted of very small sample sizes. There have been many changes made in the rehabilitation process and training of competitive athletes over the past 20 years secondary to improvements in technology, nutrition, rehabilitation equipment and techniques, and overall athletic training.5,8,11,19,25 Bansal et al3 reported on a cohort of 81 patients with hook of hamate fractures, but their results were not limited to baseball players: some patients were nonathletes, and others were club participants.

The purpose of this study was to report on return to play of a large cohort of competitive baseball players undergoing hook of hamate excision performed by a single surgeon.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively identified competitive baseball players treated between 2012 and 2017 with hook of hamate excision for acute fractures or chronic fracture nonunions. Chronic fractures were defined as pain being present for longer than 6 weeks and intraoperative findings of sclerosis or fibrous unions. All patients were treated by the senior author (S.S.). The initial cohort included patients who (1) had a hook of hamate fracture, (2) were competitive athletes, (3) were indicated for operative intervention because of pain that prohibited them from participating in competition, and (4) had previously undergone surgical treatment of the injury. Players were considered competitive if they fulfilled all 4 of the criteria of Araujo and Scharhag1: (1) training in the sport aiming to improve their performance; (2) actively participating in sport competition; (3) formally registered in a local, regional, or national sport federation as a competitor; and (4) having sport training and competition as their major activity or focus of interest. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was used to confirm the diagnosis in all athletes (Figure 1). Patients younger than 18 years were excluded from the study.

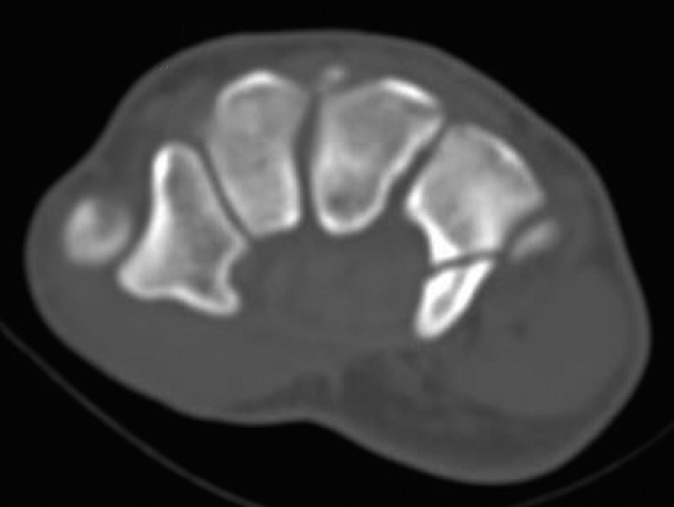

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography of the wrist showing a fracture of the hook of hamate in an 18-year-old baseball player.

Data collection was achieved through a chart review. In some cases, such as with professional athletes, return-to-play information was available as part of the public record, and when no other information was available, this was used. Variables recorded from the medical records included basic patient demographics, age at injury, sex, mechanism of injury, level of play, clinical findings, dominant/nondominant hand, preoperative imaging, surgical diagnosis, surgical treatment, time from surgery to return to play, and complications. Return to play was defined as reaching the athlete’s preinjury level and being able to perform full sport activities.

The surgical technique for excision of the hook of hamate was performed under general anesthesia. A tourniquet was used, and an incision was made over the hook of hamate. The subcutaneous tissue was dissected, and the ulnar neurovascular bundle was visualized and protected. The hook of hamate was visualized and the soft tissue attachments released. The hook of hamate was then carefully removed with a combination of a rongeur and sharp dissection. After excision of the hook, careful attention was given to ensuring that the floor of hamate was smooth. The flexor tendons were then examined to assess for any fraying or discontinuity. The wound was copiously irrigated, and the tourniquet was deflated. Finally, the wound was closed in layers, and a sterile dressing and a short arm splint were applied. No concomitant procedures were performed unless indicated by the preoperative evaluation.

Results

There were 41 baseball players identified, as shown in Table 1, all of whom were documented to have a chronic presentation of a nonunion or partial union. Our population consisted completely of male athletes, with a median age of 21 years (range, 18-34 years). All patients were competitive athletes, with 12 professional (8 Major League Baseball), 17 collegiate, and 12 high school baseball players. All 41 athletes had sustained an injury to the nondominant wrist.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 21 (18-34) |

| Sex, n | |

| Male | 41 |

| Female | 0 |

| Level of play, n | |

| Professional | 12 |

| Collegiate | 17 |

| High school | 12 |

| Injury to the nondominant wrist, n | 41 |

| Injury to the dominant wrist, n | 0 |

Thirty-four patients underwent isolated hook of hamate excision; 4 patients underwent concomitant Guyon canal release for a preoperative diagnosis of ulnar tunnel syndrome; 2 patients underwent wrist arthroscopic surgery and debridement of degenerative, triangular fibrocartilage complex tears in addition to hook of hamate excision; and 1 patient underwent hook of hamate excision with Guyon canal release and partial repair of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) to the small finger, as shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Surgical Procedures Performed

| Procedure | n |

|---|---|

| Isolated hook of hamate excision | 34 |

| Hook of hamate excision + Guyon canal release | 4 |

| Hook of hamate excision + wrist arthroscopic surgery and debridement | 2 |

| Hook of hamate excision + Guyon canal release and partial repair of the flexor digitorum superficialis to the small finger | 1 |

Patients were seen in the clinic 1 week after surgery for suture and splint removal and were released to activity as tolerated at 2 weeks postoperatively once the incision had healed. The median time to return to play was 5 weeks (range, 3-7 weeks). No hand therapy was required except for the patient who underwent repair of the FDS to the small finger. The time to return to play was similar among professional, collegiate, and high school athletes. All athletes returned to their preinjury level of activity by 7 weeks postoperatively. There was no difference in the time to return to play based on the procedure performed.

The median follow-up was at 6 weeks postoperatively (range, 2 weeks to 16 months). Six professional athletes did not follow up after their initial postoperative appointment, but data on their return to competition were able to be obtained from the public record. Two athletes (high school) had continued pain at the surgical incision site at 1 year postoperatively but were still competing at their respective levels of competition. The professional athletes were not seen back after their first postoperative visit but, based on data from the public record, none of them missed any games because of pain of the operative wrist after their initial return to play. The remainder of the patients were asymptomatic at their final follow-up visit. There were no documented surgical complications of transient sensory disturbance in the ulnar nerve distribution, transient motor weakness in ulnar nerve–innervated muscles, abnormal sensation in another cutaneous nerve, superficial infections, or wound dehiscence. The 2 cases of continued pain were attributed to pain from the scar.

Discussion

Fractures of the hook of hamate can be debilitating injuries in the athletic population, which can have a chronic, delayed presentation of vague ulnar-sided wrist pain. These injuries can be missed on standard radiographs, which can also lead to a delayed presentation. The incidence of hook of hamate fractures is believed to be 2% to 4% of all carpal fractures, but the true incidence could be higher, as the injury can easily be missed or misdiagnosed.15,21

The mechanism of injury for fractures of the hook of hamate has been well established in sports involving a bat, club, or racquet. This most frequently occurs as the shaft abuts the hook of hamate during contact.4,15,20–24 The injury occurs more often in the nondominant hand, as supported by this study, in which all of the athletes sustained an injury to the nondominant wrist. It is postulated that in baseball, this injury occurs in the nondominant batting hand because the inferior hand rests on the knob of the bat.4,21 Commercial products have been developed in an attempt to decrease the stress that is transmitted from the bat to the carpus, however no research has been conducted to assess the efficacy of these products.

The hook of hamate has very few vascular foramina, making this portion of the hamulus relatively avascular. This contributes to the propensity of fractures of the hook of hamate to progress to nonunions.12 The hamate serves as the attachment for the transverse carpal ligament, pisohamate ligament, flexor digiti minimi, and opponens digiti minimi.22,24 The FDS and flexor digitorum profundus both run adjacent to the hook of hamate as well. Chronic, nonunited fractures of the hook of hamate can lead to impingement on the adjacent branch of the ulnar nerve or tendons as well as fraying of the flexor tendons.14,18,23,24 Bansal et al3 reported on a cohort of 81 patients with hook of hamate fractures; 24 of these patients had a history of transient ulnar neuropathy before surgical intervention. In the current cohort, there were 5 patients with concomitant ulnar neuropathy confirmed by electromyography who went on to undergo Guyon canal release at the time of hook of hamate excision. One patient in the current cohort sustained a rupture of the FDS to the small finger, which was repaired at the time of excision. The complicating sequelae of these adjacent anatomic structures support early surgical intervention for fractures of the hook of hamate to prevent concomitant morbidity.

As there have been reported risks to excursion, other treatment modalities for fractures of the hook of hamate have been described in the literature. A biomechanical, cadaveric study looking at excision of the hook of hamate reported a decrease in force of the flexor digitorum profundus to the long, ring, and small fingers.10 These same results have not been confirmed in vivo,10 and there was no documentation of subjective or objective weakness in the current cohort.

Owing to the potential complications of operative intervention or alterations in biomechanics, other treatment modalities in the form of ORIF and nonoperative management with splinting/casting have been evaluated. Scheufler et al22 compared 3 patients who underwent ORIF with 4 patients who underwent excision of the hook of hamate. The patients who underwent ORIF demonstrated significantly higher grip strength values postoperatively; however, the recovery period for the ORIF group was nearly twice as long. The patients in the ORIF group were placed into a short arm cast for 2 weeks; they then began occupational therapy with limited use of the operative hand for an additional 6 weeks.22 The athletic status as well as the time to return to play was not reported in this study. In the current study, the median time to return to competitive sport was 5 weeks, which is similar to other reported timetables in the literature.2,3 Other studies comparing ORIF and simple excision of the fracture have shown simple excision to be superior to ORIF, given shorter associated recovery times and minimal to no difference in functional outcomes.4,9,17 This has led to excision of the fractured hook of hamate being favored by most surgeons.4,9,17 Nonoperative treatment has also been evaluated. This requires an extended period of immobilization and a gradual return to play, with a high nonunion rate reported.4,7 As athletes have begun training year round and have no real off-season, expedient return to play with functional results equivalent to preinjury has also led to simple excision being favored by most athletes.

There are limitations to the current study. First, it was a retrospective study, and there was a limited follow-up. If the athlete did not return to the clinic after he had been released to full competition, it was assumed that there were no complications. For the professional athletes, 6 did not follow up after their initial postoperative visit and follow-up, and return to competition was obtained from public records. As many professional athletes are treated in this clinic, there is constant communication between athletes’ trainers, agents, and medical staff. If a postoperative issue arises, then the provider is made aware, and the athlete will return for follow-up. Although these patients did not return for a documented follow-up, it is likely that their postoperative course was communicated to the surgeon. Our complication rate could potentially be underestimated given that retrospective reviews, such as this, typically identify only major complications that are documented in the medical record or documented by the trainer. As many of the patients did not follow up after returning to play, minor complications may have been managed conservatively by the patient, trainer, or primary care physician.

Conclusion

Fractures of the hook of hamate are significant injuries among baseball players, causing pain and missed time from competition. This study confirms that excision of the fractured hook provides predictable, early return to play, with a limited complication rate. The results of the current study provide treating surgeons with more data that can be used to educate patients about their expected timetable for return to play after hook of hamate excision. Further prospective research, with long-term, standardized follow-up, is needed to better assess long-term complication rates for this procedure.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: A.B. has received educational support and hospitality payments from Smith & Nephew. S.S. has received educational support and hospitality payments from Arthrex and Gemini Medical. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1. Araujo CG, Scharhag J. Athlete: a working definition for medical and health sciences research. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(1):4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bachoura A, Wroblewski A, Jacoby SM, Osterman AL, Culp RW. Hook of hamate fractures in competitive baseball players. Hand (NY). 2013;8(3):302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bansal A, Carlan D, Moley J, Goodson H, Goldfarb CA. Return to play and complications after hook of the hamate fracture surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(10):803–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bishop AT, Beckenbaugh RD. Fracture of the hamate hook. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(1):135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter AB, Kaminski TW, Douex AT, Jr, Knight CA, Richards JG. Effects of high volume upper extremity plyometric training on throwing velocity and functional strength ratios of the shoulder rotators in collegiate baseball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(1):208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carter PR, Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ununited fracture of the hook of the hamate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(5):583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins CL, Comstock RD. Epidemiological features of high school baseball injuries in the United States, 2005-2007. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1181–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crisco JJ, Greenwald RM, Blume JD, Penna LH. Batting performance of wood and metal baseball bats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(10):1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. David TS, Zemel NP, Mathews PV. Symptomatic, partial union of the hook of the hamate fracture in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(1):106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demirkan F, Calandruccio JH, Diangelo D. Biomechanical evaluation of flexor tendon function after hamate hook excision. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(1):138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ebben WP, Hintz MJ, Simenz CJ. Strength and conditioning practices of Major League Baseball strength and conditioning coaches. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(3):538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Failla JM. Hook of hamate vascularity: vulnerability to osteonecrosis and nonunion. J Hand Surg Am. 1993;18(6):1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fredericson M, Kim BJ, Date ES, McAdams TR. Injury to the deep motor branch of the ulnar nerve during hook of hamate excision. Orthopedics. 2006;29(5):456–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Futami T, Aoki H, Tsukamoto Y. Fractures of the hook of the hamate in athletes: 8 cases followed for 6 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(4):469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guha AR, Marynissen H. Stress fracture of the hook of the hamate. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(3):224–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirano K, Inoue G. Classification and treatment of hamate fractures. Hand Surg. 2005;10(2-3):151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Manske PR. Fracture of the hook of the hamate presenting as carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand. 1978;10(2):181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minami A, Ogino T, Usui M, Ishii S. Finger tendon rupture secondary to fracture of the hamate: a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56(1):96–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nicholls RL, Elliott BC, Miller K. Impact injuries in baseball: prevalence, aetiology and the role of equipment performance. Sports Med. 2004;34(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parker RD, Berkowitz MS, Brahms MA, Bohl WR. Hook of the hamate fractures in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(6):517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rettig AC. Athletic injuries of the wrist and hand, part I: traumatic injuries of the wrist. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):1038–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheufler O, Radmer S, Erdmann D, Germann G, Pierer G, Andresen R. Therapeutic alternatives in nonunion of hamate hook fractures: personal experience in 8 patients and review of literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(2):149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stark HH, Chao EK, Zemel NP, Rickard TA, Ashworth CR. Fracture of the hook of the hamate. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(8):1202–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stark HH, Jobe FW, Boyes JH, Ashworth CR. Fracture of the hook of the hamate in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(5):575–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Szymanski DJ, McIntyre JS, Szymanski JM, Molloy JM, Madsen NH, Pascoe DD. Effect of wrist and forearm training on linear bat-end, center of percussion, and hand velocities and on time to ball contact of high school baseball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(1):231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]