Abstract

Background:

Dietary supplements, such as herbals/complementary nutritionals and micronutrients (vitamins/minerals), are commonly used in the U.S., yet national data on adverse effects are limited.

Methods:

We used a nationally representative stratified probability sample of 63 emergency departments (2004–2013) to describe U.S. emergency department visits for dietary supplement adverse events.

Results:

Based on 3,667 cases, we estimated that 23,005 (95% confidence interval [CI], 18,611–27,398) emergency department visits, resulting in 2,154 (CI, 1,342–2,967) hospitalizations, were attributed to adverse events from supplements annually. Emergency department visits for supplement adverse events commonly involved young adults aged 20–34 years (28.0%; CI, 25.1%−30.8%) and unsupervised children (21.2%; CI, 18.4%−24.0%). Excluding unsupervised child ingestions, 65.9% (CI, 63.2%−68.5%) of emergency department visits for single-supplement adverse events involved herbals/complementary nutritionals; 31.8% (CI, 29.2%−34.3%) involved micronutrients. Herbal/complementary nutritional products for weight loss (25.5%; CI, 23.1%−27.9%) and increased energy (10.0%; CI, 8.0%−11.9%) were commonly implicated. These weight loss or energy products caused 71.8% (CI, 67.6%−76.1%) of supplement adverse events involving palpitations, chest pain, and/or tachycardia, and 58.0% (CI, 52.2%−63.7%) involved persons aged 20–34 years. Among adults aged ≥65 years, choking or pill-induced dysphagia/globus caused 37.6% (CI, 29.1%−46.2%) of all emergency department visits for supplement adverse events; micronutrients were implicated in 83.1% (CI, 73.3%−92.9%) of these visits.

Conclusions:

Over 20,000 emergency departments visits in the US annually are attributed to dietary supplement adverse events; these commonly involve cardiovascular manifestations from weight loss or energy products in younger adults, micronutrient ingestions by unsupervised children, and swallowing problems, usually from micronutrients, in older adults.

Herbals (botanical products), complementary nutritionals (such as amino acids) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are all considered dietary supplements by the Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act of 1994.1 Although supplements cannot be marketed for treatment or prevention of disease, they are often taken to address symptoms or illnesses, as well as to maintain or improve overall health.2 The estimated number of supplement products has increased from 4,000 in 19943 to over 55,000 in 2012,4 and approximately one-half of all U.S. adults report having used at least one dietary supplement in the past month.5 In 2007, out-of-pocket expenditures for non-vitamin/mineral supplements reached one-third of that for prescription drugs (14.8 billion USD).6,7

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is tasked with the oversight of dietary supplements, and, if a dietary supplement is found to be unsafe, FDA can have the manufacturer remove the product from the market. However, the regulatory framework differs from prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) pharmaceuticals. Manufacturers of dietary supplements containing ingredients introduced after October 15, 1994 are required to notify FDA prior to marketing and provide a rationale for ingredient safety, such as historical use. However, neither safety testing nor FDA approval is required prior to marketing of dietary supplements.8

Post-marketing adverse event reporting by dietary supplement manufacturers is only required for “serious”9 adverse events (e.g., those resulting in death or significant disability), and voluntary reporting may significantly underestimate supplement adverse events.10,11 Post-marketing regulatory actions to remove adulterated supplement products from the market have received public attention. From 2004–2012, over 200 recalls were issued for dietary supplements containing unapproved regulated substances or impurities,12 and calls for oversight changes have followed.4,13–19

The safety of dietary supplement products not known to be adulterated remains poorly described,20 however. There are limited published data quantifying the frequency of dietary supplement adverse events in the U.S.4,21–25 We used nationally representative surveillance data to estimate the number of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events and to identify associated patient characteristics, products, and adverse effects.

METHODS

DATA SOURCE & COLLECTION METHODS

We estimated the number of U.S. emergency department visits for supplement adverse events using ten years of data (January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2013) from the 63 hospitals participating in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance (NEISS-CADES) project. These hospitals comprise a nationally representative probability sample drawn from all hospitals with at least 6 beds and 24-hour emergency departments (excluding psychiatric and penal institutions) in the U.S. and its territories, with four strata based on hospital size and a fifth stratum for pediatric hospitals. As described previously,26 trained abstractors at each hospital review clinical records of every emergency department visit to identify physician-diagnosed adverse events, and report up to two implicated products and ten concomitant products. Abstractors also record narrative descriptions of the event, including preceding circumstances, physician diagnoses, testing, treatments administered in the emergency department or by emergency medical services, and patient disposition. Narrative data are coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA version 9.1). Data collection is considered a public health surveillance activity and does not require human subject review or institutional review board approval.27

DEFINITIONS

Cases were defined as emergency department visits for problems the treating clinician explicitly attributed to the use of dietary supplements. This analysis included orally administered herbals/complementary nutritionals (botanicals, microbial additives, and amino acids) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), but excluded products typically considered foods or drinks (e.g., energy drinks, herbal tea beverages). Additional products often used by consumers for complementary health, but not falling under the regulatory definition of dietary supplements, were also included in the analysis (e.g., topically administered herbals, homeopathic products). Herbals/complementary nutritionals were categorized based on common reasons for use (See Tables S1 and S2 in Supplementary Appendix for detailed definitions and specific products).

Adverse events were categorized as: adverse reactions, allergic reactions, excess doses, unsupervised child ingestions, or other events (e.g., choking). Cases involving death in or prior to arrival in the emergency department were excluded because death registration practices vary in participating hospitals and details about event circumstances are often lacking. Visits involving intentional self-harm, drug abuse, therapeutic failures, non-adherence, or withdrawal were also excluded. Categorization of symptoms was based on MedDRA-coded narratives.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Adverse event cases are weighted based on inverse probability of selection, adjusted for non-response, hospital non-participation, and to account for changes in the number of U.S. emergency department visits each year. National estimates and proportions, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated using the SURVEYMEANS procedure in SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Cumulative estimates and corresponding CIs were divided by 10 to calculate average annual estimates and CIs. Differences in weighted proportions were assessed using the SURVEYFREQ procedure with the Rao-Scott modified Chi-Square test. Linear trends in biennial estimates of emergency department visits were assessed using the SURVEYLOGISTIC and REG procedures. Biennial estimates were used to allow trend analyses to be conducted for categories of supplements with smaller numbers of cases. Population rates were calculated using intercensal estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. All analyses accounted for weighting and complex sample design. Cumulative estimates less than 1,200, based on fewer than 20 cases, or with coefficients of variation greater than 30% may be considered statistically unstable and are noted. Analyses of implicated products and symptoms were limited to cases in which a single dietary supplement product was implicated; unsupervised child ingestions were analyzed separately.

RESULTS

On the basis of 3,667 cases identified from 2004 through 2013, we calculated there was an average of 23,005 (CI, 18,611–27,398) emergency department visits for dietary supplement adverse events annually, resulting in an average of 2,154 (CI, 1,342–2,967) hospitalizations annually (Table 1). A single supplement alone was implicated in 88.3% of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events. Over half of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events involved female patients. The mean age of patients treated for supplement adverse events was 32 years; more than one-fourth of emergency department visits attributed to supplement adverse events involved persons aged 20–34 years (28.0%). Persons aged ≥65 years were more likely to be hospitalized than younger persons (16.0% vs. 8.4%, P=0.003) (Table S3 in Supplementary Appendix). One-fifth of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events involved unsupervised child ingestions.

Table 1.

Number of Cases and National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events—United States, 2004–2013*

| Characteristics | Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, No. | Annual Estimate | |||

| No. | % | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤4 | 988 | 4,965 | 21.6 | 18.9 – 24.3 |

| 5–10 | 126 | 697 | 3.0 | 2.3 – 3.7 |

| 11–19 | 308 | 1,866 | 8.1 | 6.7 – 9.6 |

| 20–34 | 930 | 6,433 | 28.0 | 25.1 – 30.8 |

| 35–49 | 558 | 3,505 | 15.2 | 13.6 – 16.8 |

| 50–64 | 399 | 2,682 | 11.7 | 9.8 – 13.5 |

| ≥65 | 358 | 2,857 | 12.4 | 10.1 – 14.7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2,121 | 13,402 | 58.3 | 56.4 – 60.1 |

| Male | 1,546 | 9,602 | 41.7 | 39.9 – 43.6 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 577 | 2,547 | 11.1 | 6.6 – 15.6 |

| White | 1,586 | 11,710 | 50.9 | 40.6 – 61.2 |

| Other | 552 | 3,166 | 13.8 | 7.5 – 20.1 |

| Unknown | 952 | 5,581 | 24.3 | 15.2 – 33.3 |

| Number of implicated products | ||||

| One supplement implicated | 3,203 | 20,303 | 88.3 | 86.3 – 90.2 |

| >1 Supplement implicated | 97 | 536 | 2.3 | 1.5 – 3.1 |

| Supplement and non-supplement implicated | 367 | 2,165 | 9.4 | 7.6 – 11.2 |

| Mechanism of adverse event† | ||||

| Adverse reaction | 1,152 | 7,663 | 33.3 | 29.9 – 36.7 |

| Allergic reaction | 796 | 5,434 | 23.6 | 21.1 – 26.2 |

| Unsupervised child ingestion | 946 | 4,871 | 21.2 | 18.4 – 24.0 |

| Excess dose | 375 | 2,330 | 10.1 | 8.8 – 11.4 |

| Other | 398 | 2,707 | 11.8 | 9.9 – 13.7 |

| Disposition† | ||||

| Discharged | 3,267 | 20,850 | 90.6 | 88.0 – 93.3 |

| Hospitalized | 400 | 2,154 | 9.4 | 6.7 – 12.0 |

| Total | 3,667 | 23,005 | 100.0 | N/A |

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, CDC.

For definitions please see Table S1 in Supplementary Appendix.

PRODUCTS

Most emergency department visits for unsupervised child ingestions of supplements involved a micronutrient product (61.9%; CI, 56.5%−67.3%). The specific product categories most commonly implicated were multivitamins (33.6%; CI, 29.0%−38.3%), iron (11.8%; CI, 8.6%−15.0%), supplements for weight loss (10.4%; CI, 7.8%−13.1%), and supplements for sleep, sedation, or anxiolysis (8.8%; CI, 6.0%−11.5%).

Excluding unsupervised child ingestions, 65.9% of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events involved a single herbal/complementary nutritional product; 31.8% involved a single micronutrient product (Table 2). A weight loss product was implicated in 25.5% and an energy product in 10.0% of emergency department visits that did not involve unsupervised child ingestions.

Table 2.

National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events by Product Category, Excluding Unsupervised Child Ingestions—United States, 2004–2013*

| Product Category† | Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events | |

|---|---|---|

| National Estimate | ||

| % | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Herbals/Complementary Nutritionals | 65.9 | 63.2 – 68.5 |

| Weight Loss | 25.5 | 23.1 – 27.9 |

| Energy | 10.0 | 8.0 – 11.9 |

| Sexual Enhancement | 3.4 | 2.4 – 4.3 |

| Cardiovascular Health | 3.1 | 2.3 – 3.9 |

| Sleep, Sedation or Anxiolysis | 2.9 | 2.1 – 3.6 |

| Laxative | 2.5 | 1.8 – 3.3 |

| Bodybuilding | 2.2 | 1.1 – 3.2 |

| Immunity Infection/Cold | 2.2 | 1.5 – 2.9 |

| Pain/Arthritis Relief | 1.7 | 1.2 – 2.3 |

| Detoxification or Cleansing | 1.4 | 0.7 – 2.0 |

| Skin or Hair Health | 1.0 | 0.6 – 1.4 |

| Microbial Additive | 0.8‡ | 0.4 – 1.3 |

| Other Specified Products | 4.8 | 3.7 – 5.9 |

| Unspecified Products | 4.4 | 3.3 – 5.4 |

| Micronutrients | 31.8 | 29.2 – 34.3 |

| Multivitamins or Unspecified Vitamins | 16.8 | 15.1–18.5 |

| Iron | 4.7 | 3.4 – 6.1 |

| Calcium | 3.4 | 2.5 – 4.3 |

| Potassium | 2.0 | 1.2 – 2.7 |

| Other Single-ingredient Vitamins or Minerals | 4.9 | 3.6 – 6.2 |

| >1 Supplement Product§ | 2.4 | 1.4 – 3.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | N/A |

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, CDC.

For definitions and specific products please see Tables S1 and S2 in Supplementary Appendix.

National estimate may be unstable (based on <20 cases).

Of 71 cases implicating two supplement products, 45 cases implicated two herbal/complementary nutritional products, 6 cases implicated two micronutrient products, and 20 cases implicated both a micronutrient and herbal/complementary nutritional product.

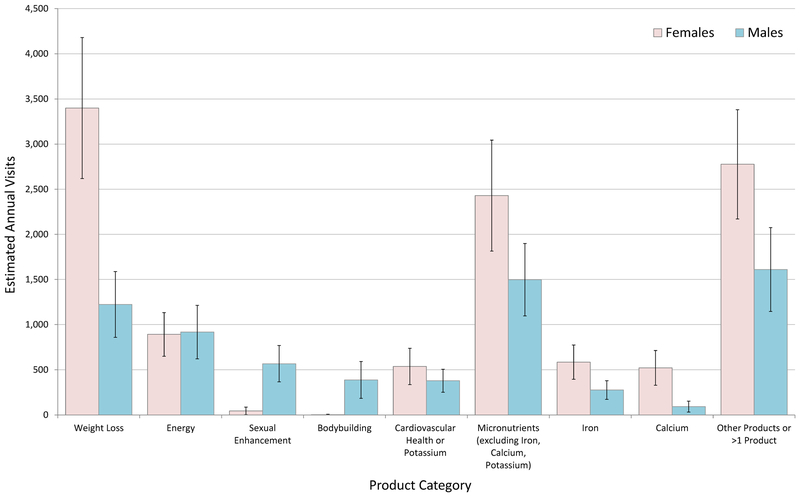

Products by Sex

Weight loss products were implicated an estimated 3,399 (CI, 2,618–4,180) annual emergency department visits by female patients, almost 3 times more than the number of annual emergency department visits by male patients (1,223; CI, 858–1,588) (Figure 1). Of the total numbers of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events, weight loss products were implicated in 30.4% (95% CI, 27.4%−33.4%) of emergency department visits among female patients versus 17.6% (95% CI, 14.3%−20.9%) among male patients. Either sexual enhancement products or bodybuilding products were implicated in 14.1% (CI, 10.5%−17.7%) of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events among male patients; there were too few cases among female patients to calculate a stable estimate.

Figure 1. National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events by Patient Sex and Product Category—United States, 2004–2013:

Excludes unsupervised child ingestions. For the following product category/sex combinations national estimates are based on <20 cases or have a coefficient of variation >30% and may be statistically unstable: Sexual Enhancement (Females); Bodybuilding (Females); Calcium (Males). National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, CDC.

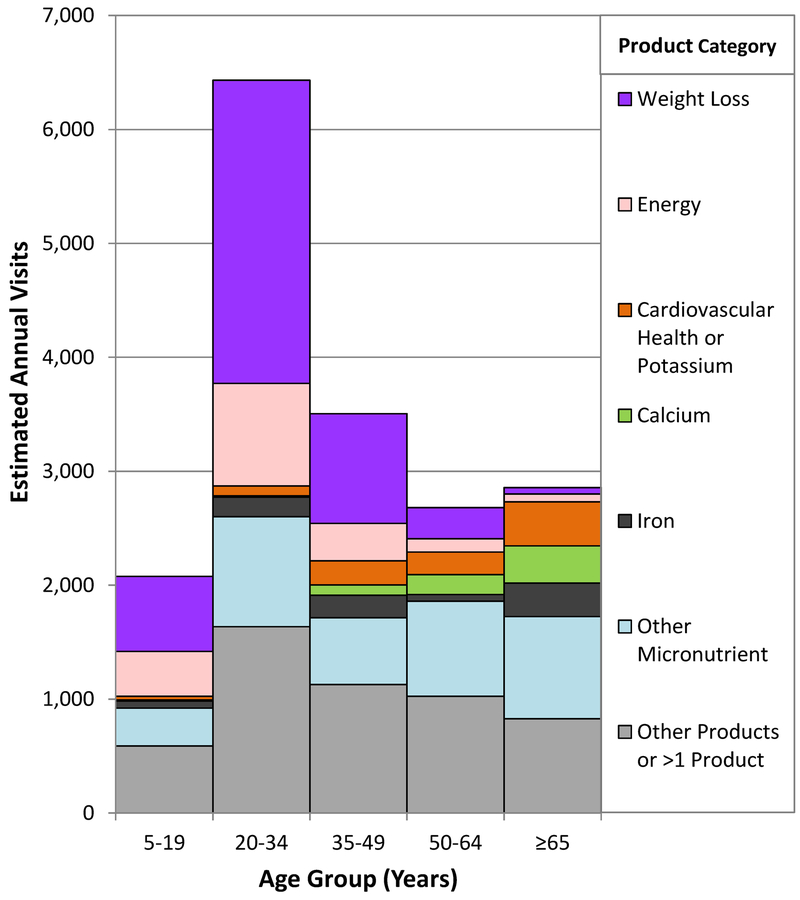

Products by Age

Excluding unsupervised child ingestions, micronutrients were implicated in two-thirds of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events among children aged ≤4 years (67.3%) and adults aged ≥65 years (62.7%) (Table S4 in Supplementary Appendix). In contrast, herbals/complementary nutritionals were most commonly implicated among the other age groups.

Weight loss products or energy products were implicated in over one-half of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events among those aged 5–19 years (51.2%; CI, 44.2%– 58.3%) and those 20–34 years (56.4%; CI, 51.8%−61.1%) (Figure 2). Weight loss products were implicated in 2,661 (CI, 1,995–3,326) annual emergency department visits for supplement adverse events among patients aged 20–34 years, a number comparable to the number of visits from all other products combined among those in each of the older age groups (Table S5 in Supplementary Appendix). Among adults aged ≥65 years, three specific micronutrients (iron, calcium or potassium) were implicated in almost one-third (29.9%; CI, 24.9%−35.0%) of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events.

Figure 2. National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events by Patient Age Group and Product Category—United States, 2004–2013:

For the following product category/age group combinations, national estimates are based on <20 cases or have a coefficient of variation >30% and may be statistically unstable: Weight Loss (≥65 years); Energy (50–64 years and ≥65 years); Cardiovascular Health or Potassium (5–19 years and 20–34 years); Calcium (5–19 years, 20–34 years, and 35–49 years); Iron (5–19 years and 50–64 years). National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, CDC.

SYMPTOMS

Cardiac symptoms (palpitations, chest pain, and/or tachycardia) were the most common symptoms from weight loss products (42.9%) and energy products (46.0%) (Table 3). Weight loss or energy products were implicated in 71.8% (CI, 67.6%−76.1%) of all emergency department visits for supplement adverse events involving palpitations, chest pain, and/or tachycardia. Most of the visits for cardiac symptoms (58.0%; CI, 52.2%−63.7%) involved persons aged 20–34 years. These cardiac symptoms were also commonly documented in emergency department visits attributed to bodybuilding products (49.8%; CI, 34.5%−65.0%) and sexual enhancement products (37.3%; CI, 25.3%−49.3%). Most patients with palpitations, chest pain, and/or tachycardia from supplement adverse events were discharged from the emergency department (89.9%; CI, 87.2%−92.6%).

Table 3.

National Estimates of Symptoms Documented in Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events from Selected Dietary Supplement Product Categories, Excluding Unsupervised Child Ingestions—United States, 2004–2013*

| Symptoms | Emergency Department Visits for Dietary Supplement Adverse Events† | |

|---|---|---|

| National Estimate | ||

| % | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Supplements for Weight Loss | ||

| Palpitations, Chest Pain, and/or Tachycardia | 42.9 | 38.4 – 47.4 |

| Headache, Dizziness, Presyncope, and/or Other Acute Sensory or Motor Impairment | 32.1 | 26.2 – 38.0 |

| Nausea, Vomiting, and/or Abdominal Pain | 18.6 | 13.6 – 23.7 |

| Mild to Moderate Allergic Reaction | 14.3 | 9.5 – 19.2 |

| Anxiety/Feeling Jittery | 12.9 | 10.2 – 15.5 |

| Severe Allergic Reaction | 4.2 | 2.3 – 6.2 |

| Seizure, Syncope, and/or Loss of Consciousness | 4.0 | 2.1 – 5.8 |

| Supplements for Energy | ||

| Palpitations, Chest Pain, and/or Tachycardia | 46.0 | 39.1 – 52.9 |

| Headache, Dizziness, Presyncope, and/or Other Acute Sensory or Motor Impairment | 34.3 | 25.7 – 43.0 |

| Nausea, Vomiting, and/or Abdominal Pain | 23.0 | 15.9 – 30.1 |

| Anxiety/Feeling Jittery | 17.5 | 11.4 – 23.7 |

| Micronutrients (Excluding Iron, Calcium, and Potassium) | ||

| Mild to Moderate Allergic Reaction | 40.6 | 34.2 – 47.1 |

| Pill-induced Dysphagia or Globus | 23.6 | 17.1 – 30.0 |

| Airway Obstruction (Due to Choking) | 19.4 | 10.7 – 28.0 |

| Headache, Dizziness, Presyncope, and/or Other Acute Sensory or Motor Impairment | 7.0 | 3.8 – 10.2 |

| Nausea, Vomiting, and/or Abdominal Pain | 6.5 | 3.2 – 9.7 |

| Severe Allergic Reaction | 6.1 | 3.7 – 8.6 |

| Palpitations, Chest Pain, and/or Tachycardia | 3.8 | 2.2 – 5.4 |

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, CDC.

Symptoms are not mutually exclusive; totals may be >100%.

The most common adverse effects from most micronutrients (excluding iron, calcium, and potassium) were mild to moderate allergic reactions (40.6%) and swallowing problems, considering choking and/or pill-induced dysphagia/globus together (41.0%; CI, 32.4%−49.7%). Swallowing problems caused most emergency department visits involving calcium products (54.1%; CI, 40.9%−67.2%), while abdominal complaints (nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain) were reported in more cases due to iron and potassium products.

Emergency department visits for supplement-induced swallowing problems were not common for patients aged 6–64 years (9.4%; CI, 7.3%−11.4%), but were common among adults aged ≥65 years (37.6%; CI, 29.1%−46.2%). Among older adults, four-fifths of emergency department visits for supplement-induced swallowing problems involved micronutrients (83.1%; CI, 73.3%−92.9%).

TRENDS OVER TIME

The number of estimated emergency department visits for supplement adverse events was 20,517 (CI, 15,187–25,847) annually in 2004–2005 and 26,779 (CI, 21,703–31,854) annually in 2012–2013; however, after accounting for population increase, the frequency of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events did not significantly change over the time period (P=0.09). There were no significant changes in estimated numbers of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events from herbals/complementary nutritionals, micronutrients overall, weight loss products, or energy products or for unsupervised child ingestions of dietary supplements; however, emergency department visits from micronutrients (excluding iron, calcium, and potassium) increased from 3,212 (CI, 1,930–4,493) annually in 2004–2005 to 4,578 (CI, 3,397–5,759) annually in 2012–2013 (P=0.03, after accounting for the increase in population).

DISCUSSION

Based on reports from a nationally representative sample of emergency departments between 2004 and 2013, we estimate that dietary supplements were implicated in an average of 23,000 emergency department visits and 2,000 hospitalizations annually. Although the numbers of emergency department visits and hospitalizations are less than five percent of the numbers previously reported for pharmaceutical products,28 dietary supplements are regulated and marketed under the presumption of safety.

While the incidence of medication-related emergency department visits was highest in older adults,28 over one-quarter (28%) of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events involved young adults aged 20–34 years. Weight loss or energy products caused over half of these visits, commonly for cardiac symptoms (palpitations, chest pain, and/or tachycardia). Notably, cardiac symptoms were documented more frequently in emergency department visits for weight loss (43%) and energy supplement (46%) adverse effects than in emergency department visits for prescription stimulants (23% of emergency department visits in a previous study using the same data source),29 which have label warnings for sympathomimetic adverse effects. Unlike OTC or prescription medications, there are no requirements to identify adverse effects on dietary supplement packaging. Clinicians could be encouraged to educate patients about potential cardiac effects from these products. However, since dietary supplement histories are infrequently obtained,30–33 particularly among younger adults,32 other opportunities for informing users of these potential adverse effects may be needed.

Unsupervised child ingestions caused one-fifth (21%) of all estimated emergency department visits for supplement adverse events, with almost two-thirds involving micronutrients. Child-resistant packaging is not required for dietary supplements other than those containing iron,34 and despite such packaging, iron supplements were the second most commonly implicated type of supplement in unsupervised child ingestions. Innovative safety packaging and targeted education on safe storage are potential interventions to reduce unsupervised child ingestions of supplements.35

Among older adults, swallowing problems caused nearly 40% of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events, with micronutrients implicated in over 80% of these visits. The Food and Drug Administration recommends pharmaceutical tablet sizes ≤22 mm and requires reporting tablet size and shape on abbreviated new drug applications.36 Similar size recommendations and reporting requirements do not exist for dietary supplements. Larger pill sizes are often used in order to include large amounts or to combine multiple micronutrients into a single pill, and many micronutrient products approaching or exceeding 22 mm are commercially available.37 Decreasing supplement pill size or utilizing other delivery vehicles such as liquids, gels, or powders, particularly for micronutrients for older adults, and educating patients to take pills one at a time may reduce emergency department visits for swallowing problems.

Limitations of our analysis should be noted. The number of emergency department visits attributed to supplement adverse events identified is likely an underestimate, as supplement use is under-reported by patients, and physicians may not identify adverse events from supplements as often as those from pharmaceuticals.30–32,38 Physicians also may have less knowledge of pharmaceutical-dietary supplement interactions than pharmaceutical-pharmaceutical interactions. Additionally, visits due to products that are generally considered foods or drinks by consumers, but that may be considered dietary supplements under the Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act (e.g., energy drinks), were not collected. However, it is also possible that emergency department physicians may incorrectly attribute certain symptoms to supplements, which could lead to overestimation.

The relatively wide confidence intervals around the reported national estimates indicate the precision limitations of using a relatively small, albeit representative, sample of hospitals. Sample size and design also prevent identification of differences between metropolitan areas, states, or regions. Nonetheless, population-based active surveillance can quantify adverse events better than voluntary reporting.11

A limited regulatory framework makes accurately monitoring supplement safety challenging.19 It was not possible to calculate rates of emergency department visits for supplement adverse events by specific ingredient, product, or type, because data quantifying supplement use are extremely limited. Estimates of overall supplement use are available from national surveys, but studies have used varying categorizations and most lack product-specific data.5,39 Identifying specific ingredients is also challenging because dietary supplements often contain multiple ingredients and similarly named products can have different ingredients. For example, “Pro Clinical Hydroxycut™ Lose Weight” lists 10 active ingredients, none of which are the three listed active ingredients in “Hydroxycut® Appetite Control”.40

We categorized supplements based on common reasons for use. In some cases, products were identified only by intended use (e.g., “weight lifting supplement”). In other cases, specific products/ingredients were named, but because some products and ingredients are marketed for multiple uses (e.g., to improve energy and sexual performance), patients’ reasons for use might have differed from assigned categories.

We estimate that over twenty thousand emergency department visits annually in the US are attributed to dietary supplement adverse events. Emergency department visits due to dietary supplement adverse events commonly involved cardiovascular adverse effects from weight loss/energy herbal products among young adults, micronutrient ingestions by unsupervised children, and swallowing problems from micronutrients among older adults. These findings can help target interventions to reduce the risk for dietary supplement adverse events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Lee M. Hampton, M.D., M.Sc. (medical officer for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]), and Ms. Kathleen Rose, R.N., B.S.N. (contractor for CDC) assisted with data acquisition and case review; and Herman Burney, M.S., Ray Colucci, R.N., and Joel Friedman, B.A., from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission assisted with data acquisition.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Pub L No. 103–417, 108 Stat 4325.

- 2.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Miller PE, Thomas PR, Dwyer JT. Why US adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:355–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Report of the Commission on Dietary Supplement Labels. (Accessed November 25, 2014, at http://web.health.gov/dietsupp/final.pdf.)

- 4.US Government Accountability Office. Dietary Supplements: FDA may have opportunities to expand its use of reported health problems to oversee products (GAO-13–244). March 18, 2013. (Accessed January 10, 2015, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/653113.pdf.)

- 5.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003–2006. J Nutr 2011;141:261–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2009:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Costs in the United States, 2007. December 22, 2011. (Accessed November 25, 2014, at http://nccam.nih.gov/news/camstats/costs/graphics.htm.)

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. New Dietary Ingredients in Dietary Supplements - Background for Industry. March 3, 2014. (Accessed November 17, 2014, at http://www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/NewDietaryIngredientsNotificationProcess/ucm109764.htm.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act. Pub L No. 109–462, 120 Stat 4500.

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General. Adverse Event Reporting For Dietary Supplements: An Inadequate Safety Valve (OEI-01–00-00180). April 2001. (Accessed January 25, 2015, at http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-00-00180.pdf.)

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. The Sentinel Initiative - National Strategy for Monitoring Medical Product Safety. May 22, 2008. (Accessed January 28, 2015, at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Safety/FDAsSentinelInitiative/UCM124701.pdf.)

- 12.Harel Z, Harel S, Wald R, Mamdani M, Bell CM. The frequency and characteristics of dietary supplement recalls in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:926–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietary Supplement Labeling Act of 2013, S. 1425, 113th Cong. (2013).

- 14.Consumers Union. Consumers Union endorses Dietary Supplement Labeling Act. August 1, 2013. (Accessed November 26, 2014, at http://consumersunion.org/news/consumers-union-endorses-dietary-supplement-labeling-act/.)

- 15.Dietary Supplement Safety Act of 2010, S. 3002, 111th Cong. (2010).

- 16.Denham BE. Dietary supplements--regulatory issues and implications for public health. JAMA 2011;306:428–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen PA, Maller G, DeSouza R, Neal-Kababick J. Presence of banned drugs in dietary supplements following FDA recalls. JAMA 2014;312:1691–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen PA. Hazards of hindsight--monitoring the safety of nutritional supplements. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1277–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starr RR. Too little, too late: ineffective regulation of dietary supplements in the United States. Am J Public Health 2015;105:478–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardiner P, Sarma DN, Low Dog T, et al. The state of dietary supplement adverse event reporting in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:962–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV, Lin CT. Dietary supplements in a national survey: Prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:1966–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2008. Health and Diet Survey. (Accessed June 2, 2015, at http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/ConsumerBehaviorResearch/ucm193895.htm.)

- 23.Dennehy CE, Tsourounis C, Horn AJ. Dietary supplement-related adverse events reported to the California Poison Control System. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2005;62:1476–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haller C, Kearney T, Bent S, Ko R, Benowitz N, Olson K. Dietary supplement adverse events: report of a one-year poison center surveillance project. J Med Toxicol 2008;4:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardiner P, Adams D, Filippelli AC, et al. A systematic review of the reporting of adverse events associated with medical herb use among children. Glob Adv Health Med 2013;2:46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jhung MA, Budnitz DS, Mendelsohn AB, Weidenbach KN, Nelson TD, Pollock DA. Evaluation and overview of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance Project (NEISS-CADES). Med Care 2007;45:S96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Distinguishing public health research and public health nonresearch. July 29, 2010. (Accessed October 27, 2014, at http://www.cdc.gov/od/science/integrity/docs/cdc-policy-distinguishing-public-health-research-nonresearch.pdf.)

- 28.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA 2006;296:1858–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen AL, Jhung MA, Budnitz DS. Stimulant medications and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2294–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hensrud DD, Engle DD, Scheitel SM. Underreporting the use of dietary supplements and nonprescription medications among patients undergoing a periodic health examination. Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:443–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA 2001;286:208–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardiner P, Kemper KJ, Legedza A, Phillips RS. Factors associated with herb and dietary supplement use by young adults in the United States. BMC Complement Altern Med 2007;7:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardiner P, Sadikova E, Filippelli AC, White LF, Jack BW. Medical reconciliation of dietary supplements: Don’t ask, don’t tell. Patient Educ Couns 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. 16.C.F.R. § 1700.14 Subchapter E—Poison Prevention Packaging Act Of 1970 Regulations, Part 1700—Poison Prevention Packaging. 38 FR 21247, Aug. 7, 1973, as amended at 41 FR 22266, June 2, 1976; 48 FR 57480, December 30, 1983.

- 35.Budnitz DS, Salis S. Preventing medication overdoses in young children: an opportunity for harm elimination. Pediatrics 2011;127:e1597–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry: Size, Shape, and Other Physical Attributes of Generic Tablets and Capsules. June 18, 2015. (Accessed June 20, 2015, at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM377938.pdf.)

- 37.Puritan’s Pride. [Multivitamin Product Search]. (Accessed January 20, 2015, at http://www.puritan.com/multivitamins-067?cm_re=LeftNav-_-Link-_-Multivitamins.)

- 38.Kaye AD, Clarke RC, Sabar R, et al. Herbal medicines: current trends in anesthesiology practice--a hospital survey. J Clin Anesth 2000;12:468–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Dietary Supplements and Prescription Medication. May 1, 2012. (Accessed January 22, 2015, at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/dsq.pdf.) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iovate Health Sciences International. Hydroxycut Weight Loss Products. (Accessed January 26, 2015, at http://www.hydroxycut.com/products/.)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.