ABSTRACT

Valproic acid (VPA) is a commonly used agent in the management of seizures and psychiatric disorders. Hyperammonemia is a common complication of VPA with 27.8% of patients having elevated levels – that is unrelated to hepatotoxicity and normal transaminases. Common side effects include obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic disorder and severe forms of hepatotoxicity. Other rare and idiosyncratic reactions have been reported, one of which is presented in our case. A 27-year old patient presented with hyperammonemia and encephalopathy as a consequence of idiosyncratic VPA reaction causing drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with severely elevated transaminases. DILI is commonly overlooked when investigating encephalopathy in the setting of VPA. Physicians should consider DILI in the context of hyperammonemia and transaminitis.

KEYWORDS: Valproic acid, drug-induced liver injury, liver failure, hyperammonemia, hepatic encephalopathy

1. Introduction

Valproic acid (VPA) is a commonly used agent in the management of seizures and psychiatric disorders [1, 2]. VPA has a well-studied side effect profile, including obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic disorder and severe forms of hepatotoxicity [3]. Elevated transaminase levels have been reported in up to 5–10% of patients while hyperammonemia is more common with 27.8% of patients [3–5]. Hyperammonemia appears to be unrelated to hepatotoxicity with most patients having normal transaminases. We present a 27-year old patient who presented with hyperammonemia and encephalopathy as a consequence of an acute drug-induced liver injury (DILI) with severely elevated transaminases. VPA is a simple eight carbon branched-chain carboxylic acid with properties of a weak acid; which has been attributed to blocking the voltage-gated sodium channels and increasing brain levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter [6].

2. Case presentation

A 27-year-old male of African descent was brought to the emergency department for altered mental status. He complained of increased sleepiness for three days, which was associated with fatigue and anorexia. The patient denied any complaints of fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, headaches, abdominal pain/tenderness, diarrhea or constipation. His documented past medical history included asthma, chronic marijuana use, chronic tobacco use, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and multiple suicide attempts. Haloperidol, benztropine, and aripiprazole were his regular home medications. He was discharged on oral VPA from a psychiatric facility one week before his presentation.

Vitals signs at presentation included a temperature of 98.2 degrees Fahrenheit, blood pressure of 117/82 mmHg, heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a respiratory rate of 20 beats per minute. The physical examination was notable for somnolence with ataxic gait, scleral icterus, and prominent asterixis. There was no lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, shifting dullness, or spider angioma. Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs were negative. Remarkable labs included an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 12,000 IU/L (8–48 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 7,000 IU/L (7–55 IU/L), ammonia of 184µmol/L (15–45 µmol/L), an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 96 IU/L (45–115 IU/L) and total bilirubin of 1.5 mg/dL (0.1–1.2 mg/dL). The patient had thrombocytopenia of 87,000 µL (150 to 450 µL) and coagulopathy with INR 2.40. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography of the head were both unremarkable. All viral hepatitis serology and toxicology panel including acetaminophen were negative except for a blood ethyl alcohol level of 9 mg/dl (0–5 mg/dl); which was also reflected in urine toxicology with the absence of other commonly tested substances.

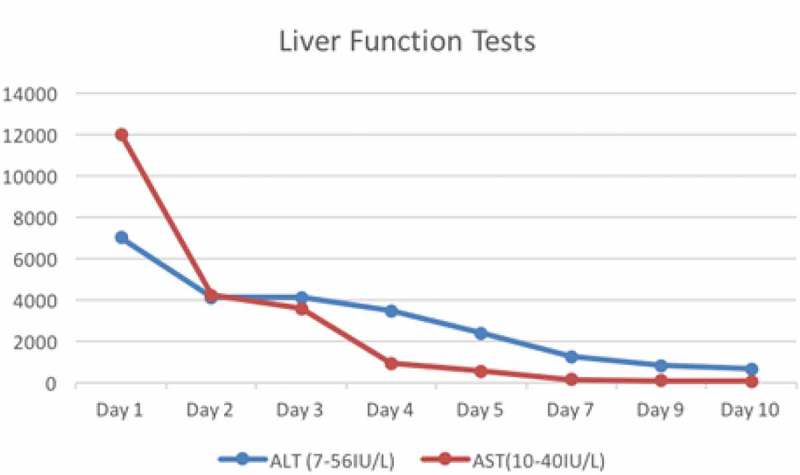

Given the patient presentation, we suspected an adverse drug reaction (ADR) to VPA. Hence, we discontinued VPA and started on lactulose for hyperammonemia. On further exploration of his history, he reported previous use of VPA which was discontinued as he did not tolerate it, but no specific diagnoses or drug reaction was documented. After the second day of discontinuing VPA, liver function tests (LFTs) were trending downward (Figure 1) and his clinical symptomology of hyperammonemia had improved; expressed by marked improvement of his mental status with minimal asterixis. By the eighth day, his ALT and AST levels dropped to 634 and 61 respectively, and his total bilirubin was within the reference range at 0.8 mg/dL. Platelet count and INR returned to normal levels. Based on his clinical course and laboratory values, a final diagnosis of VPA induced DILI resulting in hepatic encephalopathy was made. In our case, the temporal relation of the drug history and the clinical profile was strongly suggestive of adverse drug reaction to VPA and thereafter no further evaluation for any other etiologies was required.

Figure 1.

Serum transaminase levels during hospitalization.

3. Discussion

VPA has been used for seizure disorders, mood disorders, and migraine since the 1960s because of its efficacy and safety profile. However, it is not without side effects including hepatotoxicity, whose precise mechanism is still not established. Oxidative stress and some genetic factors have been speculated widely as the key mechanisms for hepatotoxicity [7]. Microvesicular hepatosteatosis is a typical feature of VPA toxicity and is suggestive of mitochondrial involvement especially involving the β-oxidation [8]. The recent study by Komulainen et al. showed the effects of VPA on mitochondria using the HepG2 cell in vitro model and further suggested an essential role of mitochondria; VPA inhibited mitochondrial respiration resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and increased cell death [9,10]. Other speculated mechanisms are lysosomal membrane leakiness, inhibition of pyruvate uptake, carnitine deficiency, drug-induced coenzyme A deficiency and rapid hepatocyte glutathione (GSH) depletion [11–13]. Syndromes like Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome (AHS), a neurometabolic disorder resulting from the mutation in mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma (POLG), is associated with increased risk of developing VPA associated hepatotoxicity [14,15].

There are two types of Drug-i+nduced liver injury (DILI) Type I and Type II. Type I being dose-dependent toxicity with transient elevation of the liver function tests and VPA can be safely used if the levels are moderately increased. Our case is consistent with type II DILI in which there is idiosyncratic drug reaction with delayed onset of weeks to months following initial exposure.

Hyperammonemia is one of the common side effects of VPA which is thought to be due to inhibition of carbamoylphosphate synthetase-I, which commences the urea cycle [16]. Although asymptomatic, hyperammonemia is common and was reported as high as 51.2% by Raja et al. and Azzoni et al. VPA induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy (VHE) is unusual. VHE is thought to be mediated by inhibition of in glutamate uptake by astrocytes which lead to cerebral edema [16–18]. Glutamine production is increased but their release is inhibited in astrocyte exposed to ammonia [19].

DILI, on the other hand, is also a rare etiology which also presents in very similar clinical symptoms. DILI in psychiatric patients is a clinically challenging diagnosis due to multiple medications. Clinicians must be vigilant and maintain a high level of suspicion when encountered with abnormal liver function tests in patients taking psychiatry mediations. In cases presenting with abnormal LFTs, like in ours, DILI should be among top differentials. Most of the cases presenting as VHE have been reported with normal or near normal LFTs [20–22].While hyperammonemia can be attributed to other causes, such as polypharmacy since our patient was also on haloperidol, benztropine, and aripiprazole; but the elevated LFTs make the diagnosis of DILI more likely.

As an essential part of adverse drug reaction (ADR), causality assessment was done using the Naranjo scale and RHUCAM score [23,24]. Naranjo scale concluded a definitive ADR with a score of 10 (> 9 is definitive) as shown in (Table 1). The RHUCAM score was calculated in our study with the following scores. Hepatocellular, second exposure, onset of < 5 days(+ 1), time from withdrawal of drug until reaction onset < 15 days (+ 1), risk factors being alcohol (+ 1), age < 55 (0), > 50% improvement in 8 days (+ 3), no concomitant therapy (0), excluded non drug-related causes: rule out (+ 2), response to re-administration positive (+ 3) with total score of 11 indicating ‘Highly Probable’ (> 8).

Table 1.

Naranjo nomogram for determining likelihood whether ADR is due to VPA rather than a result of other factors.

| Components | Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Previous conclusive reports on this reaction | 1 |

| 2. Transaminases increase (> 100x) after the suspected drug was administered | 2 |

| 3. Improvement in Transaminase levels when the drug was discontinued | 1 |

| 4. The reappearance of the adverse event when the drug was re‐administered | 2 |

| 5. Any alternative causes for the reaction | 2 |

| 6. Placebo given | 0 |

| 7. Drug detected in blood (or other fluids) in concentrations known to be toxic | 0 |

| 8. The reaction more severe when the dose was increased or less severe when the dose was decreased | 0 |

| 9. Any similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure | 1 |

| 10. Adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence | 1 |

| SCORE | 9 |

VPA in our patient was immediately stopped leading to the normalization of laboratory findings and rapid resolution of the neurological symptoms. Our case describes altered mental status, hyperammonemia, deranged LFTs as the presenting signs of DILI distinguishing it from VHE. Early diagnosis and management of DILI is very important as it has high mortality ranging from 11.7% to 17.3% [25]. Due to the poor prognosis of DILI, clinicians must do a thorough work up in the patient taking VPA with altered mental status as it may be a sign of DILI and unrelated to hyperammonemia. In VPA toxicity or any idiosyncratic reactions, evaluation with renal function tests, serum glutamate level, serum carnitine level and screening for urea cycle disorders can be considered especially in VHE. There has been some evidence of potential benefit from carnitine-pantothenic acid in cases with VPA induced DILI [26–28].

4. Conclusion

Any patient on treatment with valproate, demonstrating features of cognitive impairment, focal neurological deficit, drowsiness, must be assessed for hyperammonemia and liver function tests. Early diagnosis and prompt withdrawal of sodium valproate may lead to clinical improvement in DILI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

References

- [1].Davis R, Peters DH, McTavish D.. Valproic acid. A reappraisal of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in epilepsy. Drugs. 1994;47(2):332–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wadzinski J., Franks, R., Roane, D., et al. Valproate-associated hyperammonemic encephalopathy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(5):499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nanau RM, Neuman MG. Adverse drug reactions induced by valproic acid. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(15):1323–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Powell-Jackson P, Tredger J, Williams R. Hepatotoxicity to sodium valproate: a review. Gut. 1984;25(6):673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tseng Y-L, Huang C-R, Lin C-H, et al. Risk factors of hyperammonemia in patients with epilepsy under valproic acid therapy. Medicine. 2014;93(11):e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Silva MF, Aires CCP, Luis PBM, et al. Valproic acid metabolism and its effects on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation: a review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31(2):205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chang TK, Abbott FS. Oxidative stress as a mechanism of valproic acid-associated hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38(4):627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Begriche K, Massart J, Robin M-A, et al. Drug-induced toxicity on mitochondria and lipid metabolism: mechanistic diversity and deleterious consequences for the liver. J Hepatology. 2011;54(4):773–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Komulainen T, Lodge T, Hinttala R, et al. Sodium valproate induces mitochondrial respiration dysfunction in HepG2 in vitro cell model. Toxicology. 2015;331:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jafarian I, Eskandari MR, Mashayekhi V, et al. Toxicity of valproic acid in isolated rat liver mitochondria. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2013;23(8):617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pourahmad J, Eskandari MR, Kaghazi A, et al. A new approach on valproic acid induced hepatotoxicity: involvement of lysosomal membrane leakiness and cellular proteolysis. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26(4):545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tong V, Teng XW, Chang TKH, et al. Valproic acid II: effects on oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane potential, and cytotoxicity in glutathione-depleted rat hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86(2):436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Aires CCP, Soveral G, Luís PBM, et al. Pyruvate uptake is inhibited by valproic acid and metabolites in mitochondrial membranes. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(23–24):3359–3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li S, Guo J, Ying Z, et al. Valproic acid-induced hepatotoxicity in Alpers syndrome is associated with mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening-dependent apoptotic sensitivity in an induced pluripotent stem cell model. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1730–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stewart J.D., Horvath R, Baruffini E, et al. Polymerase γ gene POLG determines the risk of sodium valproate-induced liver toxicity. Hepatology. 2010;52(5):1791–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Verrotti A, Trotta D, Morgese G, et al. Valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2002;17(4):367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Raja M, Azzoni A. Valproate-induced hyperammonaemia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(6):631–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carr RB, Shrewsbury K. Hyperammonemia due to valproic acid in the psychiatric setting. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1020–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Takahashi H, Koehler RC, Brusilow SW, et al. Inhibition of brain glutamine accumulation prevents cerebral edema in hyperammonemic rats. Am J Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. 1991;261(3):H825–H829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Patel N, Landry KB, Fargason RE, et al. Reversible encephalopathy due to valproic acid induced hyperammonemia in a patient with bipolar i disorder: a cautionary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(1):40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Duarte J, Macias S, Coria F, et al. Valproate-induced coma: case report and literature review. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27(5):582–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Elwadhi D, Prakash R, Gupta M. The menacing side of valproate: a case series of valproate-induced hyperammonemia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(5):668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Andrade R.J., Robles M, Fernández-Castañer A, et al. Assessment of drug-induced hepatotoxicity in clinical practice: a challenge for gastroenterologists. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(3):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Devarbhavi H, Dierkhising R, Kremers WK, et al. Single-center experience with drug-induced liver injury from India: causes, outcome, prognosis, and predictors of mortality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(11):2396–2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Felker D, Lynn A, Wang S, et al. Evidence for a potential protective effect of carnitine-pantothenic acid co-treatment on valproic acid-induced hepatotoxicity. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(2):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Maldonado C, Guevara N, Silveira A, et al. L-Carnitine supplementation to reverse hyperammonemia in a patient undergoing chronic valproic acid treatment: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(3):1268–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Raskind JY, El-Chaar GM. The role of carnitine supplementation during valproic acid therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(5):630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]