EUS-guided gallbladder drainage(EUS-GBD) using a metal stent has been reported to be an alternative treatment for patients with cholecystitis at high surgical risk.[1,2,3] However, long-term deployment of metal stents may induce late adverse events, such as stent migration and food impaction.[4] This report describes a fistula created by EUS-GBD using a lumen-apposing metal stent(LAMS) in a patient with calculous cholecystitis to perform biliary drainage for cholangitis due to common bile duct stones induced by long-term LAMS deployment. An 80-year-old man with severe cardiac insufficiency presented with cholangitis due to biliary obstruction by common bile stones. This patient had undergone EUS-GBD using the LAMS for calculous cholecystitis 4years earlier, along with deployment through the LAMS of a double-pigtail plastic stent between the gallbladder and duodenal bulb to prevent stent migration. After EUS-GBD, there were not any remaining stones in the gallbladder, and a computed tomography scan did not show common bile stones, suggesting that bile turbulence or food impaction due to long-term deployment of the LAMS may have induced stone development [Figure 1]. Biliary drainage using antegrade stenting through a cystic duct from the LAMS was performed; transpapillary approach was not chosen because this patient had severe cardiac insufficiency and was therefore at risk of possibly fatal pancreatitis. It was the original intention to leave the stent permanently. An endoscope(GIF-HQ290; Olympus, Japan, Tokyo) was introduced into the gallbladder through the LAMS, and a 0.025-inch guidewire(025-inch diameter, angled tip, hydrophilic coating; Olympus, Japan, Tokyo) was deployed within the gallbladder. The gallbladder was collapsed, preventing endoscopic confirmation of the location of the cystic duct opening. Fistulography with the catheter was performed for biliary cannulation, but the contrast medium did not accumulate in the gallbladder because of leakage out of the LAMS without the balloon catheter. Therefore, fistulography was performed using a balloon catheter, of diameter 15mm(ExtractorTM Pro Retrieval Balloon; Boston, USA), inserted into the gallbladder from the LAMS. By this, the contrast medium accumulated in the gallbladder, allowing detection of the cystic duct under fluoroscopic image. Under fluoroscopic guidance, the guidewire was inserted into the common bile duct through the cystic duct, with cholangiography showing the common bile duct stones [Figure 2a]. A 7Fr double-pigtail plastic stent (Through Pass; GADELIUS, Japan, Tokyo), 10cm in length, was deployed between the common bile duct and duodenal bulb through the LAMS [Figure 2b and c] (Cystic Duct Antegrade Stenting). The following day, the patient's condition had improved and he could resume eating.

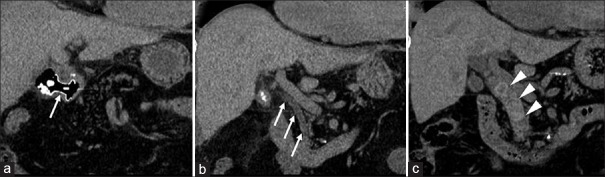

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan at the time of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage the lumen-apposing metal stent (arrow) (a) and no stones in the common bile duct (arrows) (b) computed tomography scan 4 years after EUS-guided gallbladder drainage showing many stones in the common bile duct (arrowheads) (c)

Figure 2.

Fistulography under the balloon catheter (arrowheads) inserted into the gallbladder from the lumen-apposing metal stent. Defects in the common bile duct (arrows) were indicative of stones (a).Deployment of a double-pigtail plastic stent (arrowheads) between the common bile duct and duodenal bulb through the lumen-apposing metal stent (b). Endoscopic image after the procedure, showing the stent of the luminal side (arrowheads) (c)

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that his name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal his identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamata K, Kitano M, Komaki T, et al. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasound(EUS)-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E315–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter D, Teoh AY, Itoi T, et al. EUS-guided gall bladder drainage with a lumen-apposing metal stent: Aprospective long-term evaluation. Gut. 2016;65:6–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamata K, Takenaka M, Kitano M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis: Long-term outcomes after removal of a self-expandable metal stent. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:661–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i4.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi JH, Lee SS, Choi JH, et al. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:656–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]