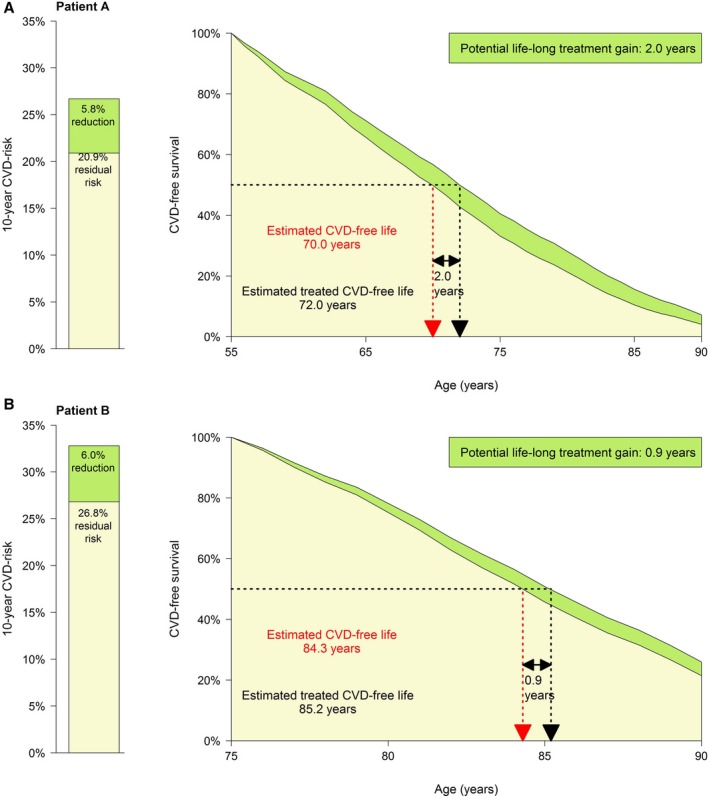

Figure 2.

Patient examples. Patient A is a 55‐year‐old woman. She is a current smoker and has no diabetes mellitus. Her systolic blood pressure is 145 mm Hg. Her laboratory values are total cholesterol, 6.0 mmol/L (LDL‐c 4.0 mmol/L); and creatinine, 70 μmol/L. She has a history of 1 location of cardiovascular disease as well as atrial fibrillation, and she has no congestive heart failure. As lipid‐lowering treatment, patient A currently takes atorvastatin 10 mg. The clinician considers raising the atorvastatin dose to 80 mg. Patient A wants to know what her expected benefit is from this change in therapy. The estimated 10‐year risk for patient A is 26.7%. Her life expectancy free from recurrent cardiovascular disease is 70.0 years. When she would take atorvastatin 80 mg instead of 10 mg, this would reduce her 10‐year risk to 20.9% (−5.8%, or 10‐year NNT, 17). The change in therapy would increase her estimated cerebrovascular disease–free life expectancy with 2.0 years to 72.0. Patient B is a 75‐year old male who does not smoke and has no diabetes mellitus. His systolic blood pressure is 140 mm Hg. His total cholesterol is 5.0 mmol/L and creatinine 80 μmol/L. He has a history of 1 location of cardiovascular disease, no atrial fibrillation, and no congestive heart failure. As lipid‐lowering treatment, patient B currently takes atorvastatin 10 mg. The clinician considers raising the atorvastatin dose to 80 mg. Patient B wants to know his expected benefit from this change in therapy. The estimated 10‐year risk for patient B is 32.8%. His life expectancy free from recurrent cardiovascular disease is 84.3 years. When he would take atorvastatin 80 mg instead of 10 mg, this would reduce his 10‐year risk to 26.8% (−6.0%, or 10‐year NNT, 17). The change in therapy would increase his estimated cerebrovascular disease–free life expectancy with 0.9 years to 85.2. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; NNT, number needed to treat.