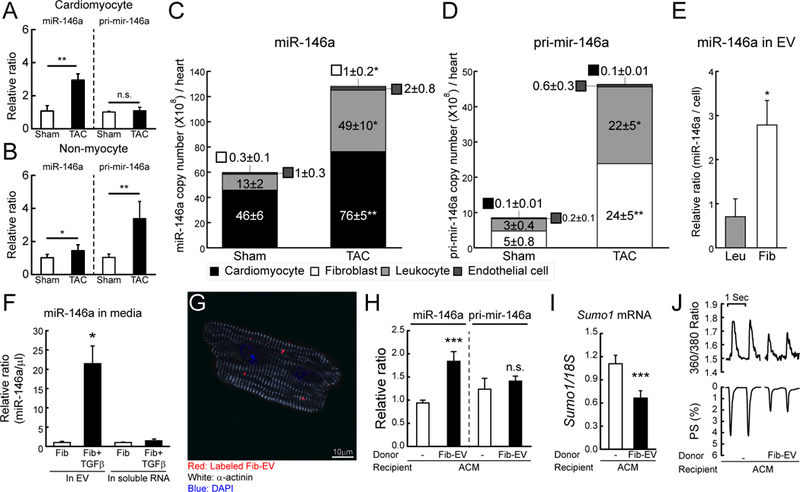

Figure 6: miR-146a is transferred from fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes through an EV-mediated mechanism.

A and B, Changes in miR-146a and pri-mir-146a levels in isolated cardiomyocyte (A) or non-myocyte (B) fractions from mouse hearts of sham and TAC operated mice (TAC, 6 weeks after TAC) (n=3). The RNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA. C and D, Copy number of miR-146a (C) and pri-mir-146a (D) in sorted cardiac cells from sham and TAC operated mice (6 weeks after TAC) (n=5). E, Levels of miR-146a in isolated EVs from leukocyte (Leu) or fibroblast (Fib)-cultured media. F, Levels of miR-146a in isolated EVs from fibroblast-cultured media with/without TGF-β. G, Representative confocal microscopic image of isolated cardiomyocytes treated with labeled EVs for 24h. H and I, Levels of miR-146a, pri-mir-146a (H) and SUMO1 mRNA (I) in isolated cardiomyocytes treated with/without fibroblast-derived EVs for 24h (n=3). J, Representative trace of calcium transient (top) and cardiac contractility (bottom) (n=60–80 cells/3 hearts). *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01, ***, p<0.001 versus the indicated control, as determined by Student’s t-test. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. in all panels.