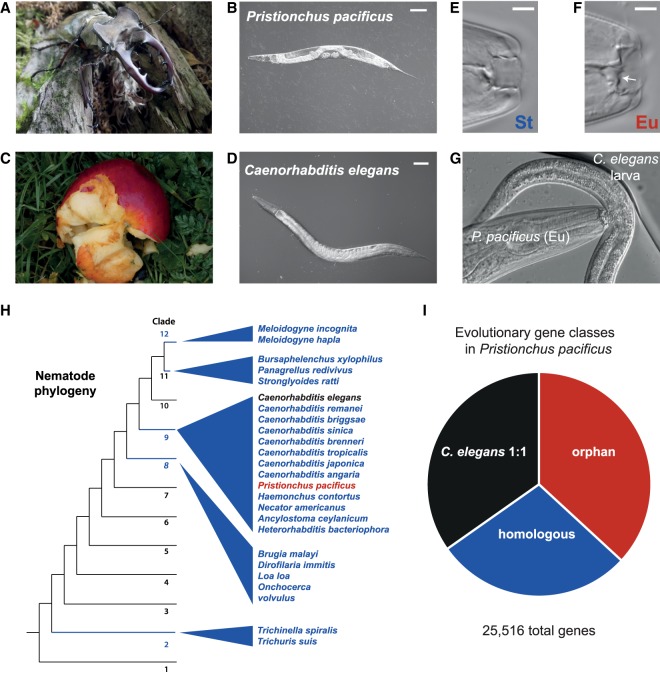

Figure 1.

Comparison of Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans and phylogenetic relationship. (A,B). P. pacificus is often found in a necromenic relationship with insect hosts, preferentially scarab beetles, in the dormant dauer state. When the beetle dies, worms exit the dauer stage to feed on bacteria that bloom on the decomposing carcass. (C,D) C. elegans, the classic nematode model organism, is often found in leaf detritus and rotting fruits. Example rotting apple photo taken by M.S.W. (E–G) P. pacificus has become an important model for developmental (phenotypic) plasticity. Adults can adopt (E) a narrow mouth form with one tooth (stenostomatous [St]) that makes them strict bacterial feeders. However, the “boom-and-bust” life cycle creates significant competition for resources, and under crowded conditions adults can develop an alternative mouth form (F) with a wider buccal cavity and an extra tooth (eurystomatous [Eu]) that allows them to prey on other nematodes. (G) Shown here is a eurystomatous P. pacificus preying on a C. elegans larva. (H) A schematic phylogeny of nematodes that was generated based on the publications of Holterman et al. (2017) and Van Megen et al. (2009). (I) Breakdown of P. pacificus genes by evolutionary category: One-to-one orthology with C. elegans (C. elegans 1:1) is the most conserved, followed by genes sharing homology with at least one gene from the 24 other nematodes (homologous), and finally genes that are only found in Pristionchus (orphan). All categories were defined by BLASTP homology (e-value ≤0.001) (Methods).