Abstract

Dignity Therapy (DT) provides, for patients with a serious illness, a guided sharable life review through a protocolized interview and the creation of a legacy document. Evidence is mounting in support of the use of DT for patients with a serious illness; however, it is unclear whether DT has effects on family members. The purpose of this article is to provide a systematic literature review of the effects DT has on family members of patients who receive DT. Using a PubMed search with key terms of ‘Chochinov,’ ‘family,’ and ‘dignity care,’ a total of 18 articles published between January 2000 and July 2016 were identified and included in this review. This systematic review was helpful in identifying the strength of the evidence and gaps in the literature focused on DT and expected or actual effects on the DT recipient or family members. Findings identify the need to conduct further research related to the feasibility, acceptability, and effects of DT for family members. Future research should focus on understanding whether and how family members may benefit from receiving the legacy document and if the timing of family member involvement plays a role in the outcomes of DT.

Keywords: Dignity Therapy, Literature Review, Family Member, Spiritual Care

Introduction

Dignity Therapy (DT) provides, for patients with a serious illness, a guided sharable life review through a protocolized interview and the creation of a legacy document.1 During DT, patients have the opportunity to record their life story and values in a document that reviews memories and offers statements and personal messages that are important to them. Once the legacy document has been edited to the patient’s satisfaction, he or she can share it with family and friends. Evidence is mounting in support of the use of DT for patients with a serious illness2; however, it is unclear whether DT has effects on family members.

Patients diagnosed with a serious illness often have family members or friends accompany them through the entire trajectory of the serious illness. One of the main goals of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of not only the patient but also the family members. Providing care to a loved one can take a toll both mentally and physically on the family member. Some patient services now offer supportive services to family members as part of comprehensive care. DT has the potential to benefit families as well as the patient. Currently there is a small body of literature that examines the effects of DT on families but no systematic literature review. The purpose of this article is to provide a systematic literature review of any of the effects of DT on family members of patients who receive DT from both the patient and family perspectives.

Methods

Search strategy

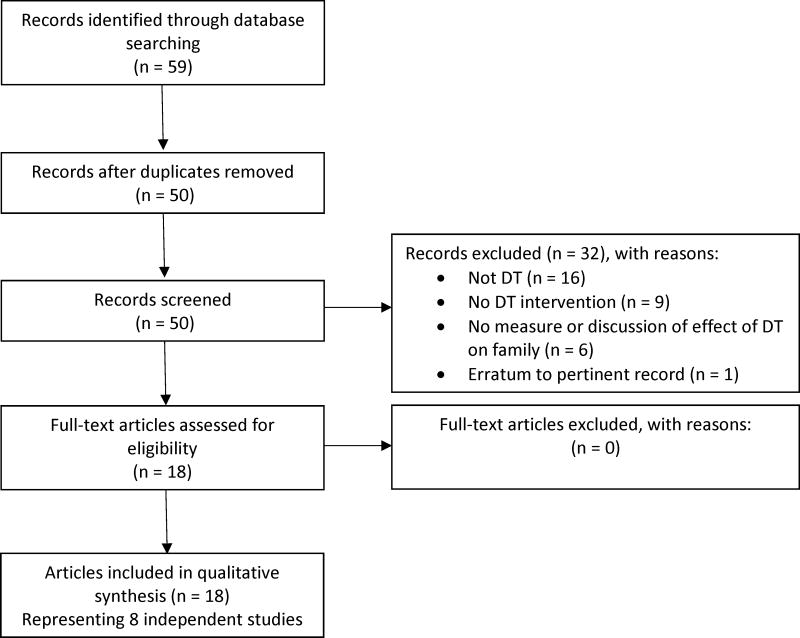

The authors used the PubMed database to obtain an initial list of articles for review. This database was selected because of its high reliability and abundance of publications. Since DT was first developed in the early 2000’s this search was restricted between January 2000 and July 2016 and included the terms ‘Chochinov’ and ‘family’ and ‘dignity care’ and ‘family’. Following PRISMA3 systematic review guidelines, 59 references were downloaded into EndNote X7.54. Duplicate articles were deleted and 50 articles were retained (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Systematic Review Process

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The authors conducted a two-stage review, first of abstracts and then of full text articles. The following rationale for inclusion was used: Only studies of DT as an intervention with report of family outcomes were retained. To best represent the current literature and state of the field, the authors were inclusive in interpretation of reportage on family outcomes; Table 1 presents studies that investigated family outcomes through the inclusion of family members as study participants in interventions. Table 2 presents studies in which only the patient participant gave their perspective of the expected impact of DT on their family members. The authors also included an article that reports the perspective of hospice care workers who witnessed DT interventions with patients about its perceived impact on family members in Table 2. In total, eighteen articles that included qualitative and quantitative studies of the impact of DT on family members and caregivers of patients receiving the therapy were retained. The retained 18 articles represent eight different studies. Studies that focused on the development of the DT therapy model and other dignity care were excluded.

Table 1.

Studies of Dignity Therapy Including Measures or Analysis of Impact on Family Members

| Study | Sample | Design | Measures | Family member Findings |

|

| ||||

| Quantitative studies | ||||

|

| ||||

| Aoun et al., 20155 Bentley et al., 20146 | Australian sample; 27 pts, living in the community diagnosed with motor neuron disease (MND) 18 family members | Single group; Pre/post testing of DT Assessment: Baseline; post-test for family caregiver 1 week after DT document provided | Family members’ feedback elicited on benefits to pts and themselves, including decreased caregiver stress, increased sense of hope, and better preparation for end of life Outcomes for caregiver:

|

88.9 % thought DT was helpful to their family member |

| 70% thought DT document would continue to comfort them and their family; would recommend it to others with MND | ||||

| 33.3% thought DT improved their feelings of hopefulness and decreased stress | ||||

| Feasibility assessed by family caregiver involvement in DT, time taken for session, and accommodations or deviations from DT protocol | ||||

| Bentley et al. reported 29 pts and 18 family members | 50% felt it helped prepare them for loved one’s end of life | |||

| No significant changes pre/postintervention related to caregiver burden, hopefulness, anxiety, or depression | ||||

| Also reported by Bentley et al. | ||||

| At baseline half had moderate to severe anxiety | ||||

| Controlling for functional decline there was no significate effect of DT on CG burden | ||||

|

| ||||

| Chochinov et al., 20127 | Canadian sample; 12 cognitively intact and 11 cognitively impaired frail elderly in long-term care 5 cognitively intact residents’ family members provided feedback 9 cognitively impaired residents’ family proxies, provided feedback | Single group trial of DT Assessment: 2 months post-intervention for families of cognitively intact residents |

Evaluation

|

Cognitively intact residents’ family members: 4/5 agreed DT was helpful to family member and 3/5 agreed it was an important part of care. 4/5 would recommend DT to others. Some believed DT would continue to be a source of comfort to family (2/5) or change how the HCP appreciated the pt (1/5). No family members thought DT would change how they appreciated patient. |

| No specification of benefits around dignity, suffering, or preparation for future were noted for these caregivers. | ||||

| Cognitively impaired pts’ family proxies unsure of direct benefits of DT for their family member; All family proxies would recommend DT to others. Majority agreed DT helped them personally (8/9), would continue to be source of comfort (8/9), and may change how they appreciate the patient (6/9) | ||||

| No specification of benefits around meaning, purpose, suffering, or dignity | ||||

|

| ||||

| Johns, 20138 | US sample; 10 pts with metastatic cancer from community or outpatient oncology unit 6 family members | Single group trial of DT Family members completed satisfaction surveys and provided feedback on DT document within 1 month of receipt | Satisfaction survey | All family members found DT document helpful and derived meaning from it. All indicated it increased pt’s sense of dignity, life meaning, and purpose. |

| The majority (75%) of family members reported DT decreased patient’s sense of suffering. | ||||

|

| ||||

| McClement et al., 20079 | Canadian and Australian sample; 60 family members of deceased terminally ill pts | Single group Assessment of family members 9–12 months after death of patient | Family members completed evaluation that assessed perceived impact of DT on pts and families | 95% of family members indicated DT was helpful to pt. |

| Many family members reported DT increased pt’s sense of dignity (78%) and purpose (72%). | ||||

| Family members felt DT helped during grief (78%) and would continue to comfort family (77%). | ||||

| DT reported to help pts prepare for death (65%), was an important part of care (65%), and decreased patient suffering (43%). | ||||

| Families made an average of 5.6 copies of DT document to share with family and friends. | ||||

| Some family members had concerns related to inaccurate or incomplete documents; 19 actively participated in the DT session; In all cases where family member was dissatisfied with DT, they had not been an active participant. | ||||

| Ethical issues raised in two cases (i.e. family members request unedited interview audio-tape). | ||||

|

| ||||

| Qualitative studies | ||||

|

| ||||

| Study | Sample | Methods | Main Study Finding | |

|

| ||||

| Goddard et al., 201310 | 27 UK older adults living in care homes | Framework analysis of qualitative interviews conducted; interviews related to family views on the impact of DT for themselves and patient | DT document was liked by most family/friend. 1 had concerns regarding the content of document and 2 had concerns with negative feelings surrounding receiving and reading document. | |

| Related articles: Hall et al., 2009;25 Hall et al 2011;17 Hall et al., 201226 | 14 family/friend/staff of older adults living in care homes who received DT documents before patient’s death | |||

| DT found to be helpful to family member/friend and pt. | ||||

| Interaction with therapist viewed by family/friend as main benefit for pts, reappraisal and reminiscence also described as a positive benefit for pt. | ||||

| 5 family/friend concerned about feasibility of DT in care homes (i.e. memory loss and strain this may cause); 6 concerned with impact of DT on pts who were not distressed or feel loss of dignity. | ||||

| 7 family/friend felt their knowledge regarding patient increased | ||||

| Most felt DT document promoted communication and would be helpful during bereavement. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hall et al., 201311 | 29 UK pts with advanced cancer, sample from Hall et al., 2011 | Framework analysis of qualitative interviews | 3/9 family members felt DT helped with generativity concerns; 5 felt DT document was incomplete and indicated negative experiences. | |

| Related article: Hall et al., 200927 | ||||

| 9 family members of pts from intervention group | ||||

| 3 family members felt DT helped increase patient’s sense of self-respect; 2 family members felt pts had an increase in hope. | ||||

| 4 family members felt DT document improved family communication. 6 family members felt DT was physically or emotionally taxing for their loved ones. Others felt process distressed their loved ones due to them not accepting their prognosis. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Case studies | ||||

|

| ||||

| Study | Sample | Implementation | Discussion | |

|

| ||||

| Chochinov, 200212 | 62 y/o Canadian patient with metastasized lung cancer receiving comfort care only | DT protocol implemented with pt; investigator interviewed pt, pt’s wife, and treating clinician to discuss concepts of dignity in care and the DT protocol. | Pt’s wife reported DT document would be way remembering pt. Reported DT document would comfort her. | |

|

| ||||

| Hall et al., 201313 | 3 UK pts with advanced cancer in high distress, sample from Hall et al., 2011 | Focus on ‘dignity-related problems’ expressed by pts; qualitative interviews with 3 recipients of DT documents produced by pts | All pts thought DT had helped or would help family at 1 and 4 weeks post intervention. | |

| Related article: Hall et al., 201117 | ||||

| Family member of 1 patient felt DT had not changed how pt felt about herself; felt process of DT was upsetting for both, but worthwhile. | ||||

| Child of 1 pt said DT document made her feel proud of her mother. | ||||

| Family friend of 1 pt appreciated being allowed to read DT document; thought DT allowed pt to reflect on what was important; may have helped her children work through issues of her terminal illness. Also discussed disappointment about negative content. | ||||

| DT documents of pts in high distress may need careful editing to counterbalance pt’s “negative frame of mind” in consideration of impact on recipients. | ||||

ALS-FRS = Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale; DTPFQ = Dignity Therapy Patient Feedback Questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HHI = Herth Hope Index; ZBI = Zarit Burden Interview

Table 2.

Studies of Dignity Therapy without Direct Measures of Effects on Family Members

| Study | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Quantitative studies | ||

|

| ||

| Bentley, et al., 201414 | Australian sample; | Pts felt DT would be helpful to family members during bereavement. |

| 29 pts diagnosed with motor neuron disease | ||

|

| ||

| Chochinov et al., 200515 | Canada and Australian sample; | 81% of participants who completed DT felt it helped or would help family; this related to pts having increased sense of purpose and meaning and decreased sense of suffering, as well as increased will to live. |

| 100 terminally ill pts in hospital, nursing home or home | ||

|

| ||

| Chochinov et al., 201116 | Canada, Australia, and US sample; | Pts assigned to DT group (n=165) [compared to the client-centered care (n=136) or standard care group (140)] significantly more likely to report a change in how their family saw and treated them; reported DT would be helpful to family. |

| 441 pts receiving palliative care in hospital, hospice, or home | ||

|

| ||

| Hall et al., 201117 | UK sample; | Participants rated benefits of DT or taking part in the study (control group) at 1 week f/u and 4 week f/u. Effect sizes were medium (0.50) to large (0.80) for agreeing that DT had or would help their family at 1-week f/u (Cohen’s d= .62) and 4 week f/u (Cohen’s d= .88). No significant difference between control and intervention groups at either f/u. |

| 45 pts with advanced cancer | ||

|

| ||

| Montross et al., 201318 | US sample; | 92% felt DT would help the family in the future. |

| 18 hospice staff who had referred a patient to DT | ||

|

| ||

| Vergo et al., 201419 | US sample; | Of 9 pts who completed the study, 88% felt DT would be helpful to family. |

| 15 pts with stage IV colorectal cancer | ||

|

| ||

| Qualitative study | ||

|

| ||

| Ho et al., 201320 | 16 older Chinese palliative care pts with cancer | Framework analysis of qualitative interviews |

| Related articles: Ho et al., 201328 | Transgenerational unity (i.e. family connections) emerged as important theme; participants wanted to be closer to their family members. Closeness of family members provided a sense of spiritual connectedness. | |

| Pts had a great need to regain their identity within family context in order to heal from existential pain of dying. | ||

|

| ||

| Case studies | ||

|

| ||

| Avery & Savitz, 201121 | 55 y/o man with severe mental illness | Pt reported DT allowed him to better communicate with his children. Adult children stated they “could now better understand their father.” |

|

| ||

| Lubarsky, et al., 201622 | 46 y/o man with history of alcohol use disorder | Pt felt DT helped bring him closer to family. |

Results

Of the 18 articles, five articles were quantitative uncontrolled feasibility studies of DT that included some measure of effect on family members and caregivers.5–9 Two articles were qualitative studies of DT that included analysis of the impact of DT on family members and caregivers.10,11 Two articles were case studies.10,11 A pilot case report of DT was written during Chochinov’s development of the therapy protocol, and included an interview with the patient’s wife, who reported the DT document would be a comfort to her.12A case study of 3 patients with advanced cancer in high distress included interviews with family members, who reported mixed impressions of the therapy’s effectiveness on the patient and comfort to them.13 All studies that include some measure of effect on family members and caregivers are presented in Table 1.

The other nine articles were a mix of quantitative and qualitative analyses and case reports that included some consideration of the family member or caregiver of the patient receiving DT in their measurement, analysis, or discussion of DT, but these articles did not include direct measurement of any effect on the family member or caregiver (Table 2).14–22 Five of these nine articles represent studies in which patients receiving DT responded to some variant of the question if DT would “help” their family members or caregivers. Findings from these articles suggest that patients who receive DT feel it will be helpful to family members.14–17,19 One report18 represents a qualitative analysis of views of hospice workers who referred a patient to DT; 92% of these hospice workers reported they felt DT would help family members in the future. One article20 presents a framework analysis of qualitative interviews, which confirmed family closeness was an important component of dignity in Chinese palliative care patients with cancer. Two case reports of non-terminally-ill recipients of DT included findings that the therapy bettered communication or closeness between the patient and family members.21,22 These 9 articles are included to reflect the full current state of the science of DT and family members; however, this literature review is primarily focused on the direct effects of DT on the family. An earlier review of the patient-focus of these studies (excluding Lubarsky, 2016, because it was not yet published) has been published.2

Sample and Settings

The investigators of the studies sampled from populations in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The study sample sizes ranged from six to 60. Family members in these studies cared for older adults as well as individuals with motor neuron disease, metastatic or advanced cancer, and terminal illness. These individuals received care at home, in a rehabilitation center, or in a long-term care setting.

Design

Two of the quantitative studies included a pre/post-test single group design; only one study included a pre-intervention baseline measurement.6 Post-test measures included timeframes of one week after receiving the DT document,5,6 one month after receiving the document,8 two months after the intervention,7 and nine to 12 months after the patient died.9 The two qualitative studies used the Dignity Framework approach with both deductive and inductive analytic techniques.

Intervention

Chochinov’s DT protocol was implemented in all quantitative studies and research staff in all of the quantitative and qualitative studies were trained in DT by Chochinov. In 3 of the quantitative studies, at least some family members were involved during the DT interview process, either at the request of the participant or because the participant was cognitively impaired.6,7,9 In the two qualitative studies, caregivers included not only family members but also friends, and one qualitative study included care staff.10

Measures and approaches

Investigators for all five of the quantitative studies examined outcome measures post-intervention using a variety of methods including having family members complete a modified feedback questionnaire form,6,7 a satisfaction survey,8 an evaluation form focused on psychosocial and bereavement issues,9 or one focused on decreased caregiver stress and increased sense of hope.3 Only two studies had primary and secondary outcome measures of the effectiveness of DT related to the caregiver.5,6 Both studies included the following measures: burden (primary), hope, anxiety, depression, and physical function.5,6 Specifically, the tools for measurement of the primary and secondary outcomes for both studies were the Zarit Burden Inventory (primary), Herth Hope Index, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.5, 6

To facilitate the interpretation of the results, the studies were arranged by three main types of foci that emerged from the review: feasibility of family involvement in DT, acceptability of DT from family perspective, and effects of DT for family members. Below, the key findings from eight studies reported in the nine articles with information about feasibility, acceptability, and effects of DT for family members are summarized. Effects include findings from primary and secondary outcomes.

Feasibility

Feasibility of DT in relation to the involvement of family members was reported in four of the articles.5,6,9,10 For example, Bentley and colleagues reported the majority of family members had some role in the DT process, with 12 out of the 18 family members assisting with the interview and editing process. There was no significant difference in distress levels between family members who were part of the DT process and those who were not;6 however, the DT sessions took longer when family members participated. Family members contributed in many ways including being in the sessions for support, contributing to the narrative as requested by the patient, and serving as a proxy. McClement and colleagues reported that of the 100 participants who completed DT, there were 60 cases where family members provided feedback related to their personal experience, and 17 of these 60 family members (28%) were present for the DT sessions.9

Acceptability

Acceptability of the intervention was based on the family members’ perception of DT. Investigators used a variety of questions to measure the acceptability of DT for family members. Only one study included a report of how DT personally affected family.4 In that study, 18 family members supported 29 patients with motor neuron disease who received DT.4 Bentley and colleagues reported that 50% of the family members (n=9) agreed or strongly agreed that DT was helpful to them, whereas 22% (n=4) indicated it was not helpful. A qualitative study, with nine family members of persons with advanced cancer, explored family members’ perspectives of the impact DT had on the patients and themselves.9 Six of the nine family members felt DT sometimes had been physically or emotionally demanding for their loved ones due to not accepting their prognosis and five family members felt the document was incomplete.9 Six family members felt the generativity document had improved communication while three family members felt DT had improved generativity issues, such as the comfort the document brought to them.9

Effects

A variety of articles reported perceptions of effects. For example, Bentley and colleagues reported that 28% of the 18 family members thought DT helped them reduce feelings of stress or prepared them for the end of life for their loved one, whereas 33% of the 18 family members reported DT helped increase their feelings of hopefulness for the future.6 Investigators of all five quantitative studies reported that the majority of family members felt the DT document would be a continued source of comfort to their family and themselves and would recommend DT to other friends and family. Both qualitative studies reported that family members felt the DT document enhanced family communication.10,11

Evidence of DT’s effects based on family members’ perceptions of the benefits to their loved one was positive. All five quantitative studies reported the majority of family members felt DT was an important part of care. For example, McClement and colleagues conducted a study with 60 family members of terminally ill patients who had taken part in DT and had since died and the family members reported perceptions that can bring comfort to family. For example, 68% of the 60 family members felt DT helped increase their loved one’s sense of dignity and 71.7% felt DT increased their loved one’s sense of purpose. Reports among the studies of family members indicated that DT decreased their loved one’s suffering; the suffering score decreased by 20% for five subjects7 to 75% for six subjects.8

Although family members were generally positive about the effect of DT on their family member, some family members had concerns related to inaccurate or incomplete documents,9–11 the process being physically and emotionally difficult for their loved one,10,11 as well as family members experiencing negative feelings related to reading the document.11 For example, in a study with nine UK family members of patients with advanced cancer who had participated in DT, five family members felt the DT document was incomplete due to family members not being mentioned, or because the patient had not accepted that he or she was nearing end of life.11 Additionally, six family members felt the patient experienced emotional stress from discussing important issues with someone they had just met and from DT’s implicit message of the nearness of life’s end.11

Only two studies used validated scales to measure the effects (perceived burden, hopefulness, anxiety, and depression) of DT related to the family member; findings were mixed.5, 6 Bentley and colleagues reported a significant pre-post increase in family member burden in relation to a decrease in their loved one’s physical functioning, which was potentially due to their motor neuron disease.6 In contrast, Aoun and colleagues reported no significant pre-post changes in family member burden.5 Both studies reported no significant pre-post findings for change in self-reported anxiety, depression, or hopefulness in family members; however, sample sizes were small and did not provide power to detect small outcome effects.5,6 We found no studies of DT provided to the family member that was adapted to allow them to say what they wanted to their ill family member.

Discussion

This systematic review was helpful in identifying the strength of the evidence and gaps in the literature focused on DT’s expected or actual effects on family members of patients who engaged in DT. Studies in the review mainly focused on the family member’s perspective of how DT helped his/her loved one and showed that it was feasible and acceptable to include family in the studies. The effects of DT on the family have not been well demonstrated in adequately powered studies, despite the fact that serious illnesses affect not only the patient but also family members. This review complements other recent review2 by providing a better understanding of the effects of DT on family members of patients who receive DT and highlights several important findings.

Family members’ involvement in the DT process

The purpose of DT is to provide an opportunity for individuals with a serious health condition to address psychological and spiritual needs through a life review interview and the creation of a legacy document. As this review shows, DT has been used in many different populations, including patients with cancer19,23 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis14 and with frail, older adults.7 Family members are an important part of DT as they are often the recipient of the legacy document. However, as this review shows, some researchers include family members earlier in the DT process. For example, family members may be included in the creation of the legacy document by allowing them to support the patient during the interview and editing process. Some researchers have involved family members in the creation of the legacy document at the request of the patient, or because patients had a cognitive or speech impairment rendering them unable to complete the legacy document without assistance from family members. It is unclear, however, how involving family members in the interview and editing process affects (1) the patient’s quality of life, sense of purpose, and dignity or (2) the participating family member or subsequent family function. Future studies are needed to better understand the effect of involving family members in DT prior to the delivery of the legacy document so that clinicians can be guided on how to involve them.

The study of DT on family members

Although the main focus of DT is on the patient, family members are also an important part of DT. Most research has focused on the effect DT has on the patient, but some studies also explored the effects for family members.2 Since family members often experience emotional distress as well as caregiver burden, they could benefit from participating in the creation of the DT document or receiving it or possibly creating their own statement to the patient. The effects identified in the reviewed studies included positive effects for most and negative feelings for some family members. One study, not included in this review as it was published outside the review dates, evaluated the effects of DT on patients (N=80) with a terminal illness and their family members (N=25).24 Findings from the study revealed no significant difference in the Mental Health Inventory (MHI) scores between family members in the DT group and the standard palliative care group at baseline or four days post-intervention.24 Juliao reported that these findings may be due to high baseline MHI scores in both groups. It is not clear from the available evidence what family-related outcomes would be affected by participation in the creation or receipt of the DT legacy document. Sense of dignity and purpose, family communication, transgenerational connections, and bereavement were areas identified as potential foci for the effects of DT. Future studies should be designed to investigate these areas as targets for determining the potential effects of DT on the family, its functioning and its responses in other end-of-life situations.

Research agenda as it relates to the family and DT

Future research should be focused on several areas, including the process of implementing DT and the short- and long-term effects of DT on individual and collective family functioning. Research is needed to determine if, when and how the DT interview and legacy document creation should involve a family member. It is also important to determine whether there are variations in effects for family members who do and do not participate in the DT interviews or as a result of when the family member receives the legacy document (i.e., before their loved one’s death or after). Determining the family-related variables sensitive to effects of the DT legacy document should also be the focus of future research. Based on the findings of prior studies, family communication and connectedness, as well as the family member’s anxiety, hopefulness, and grief are potential variables that may be affected by DT. Specific features of DT also need further study. For instance, editing the document offers patients a chance to rethink, in the setting of an interaction with a trained professional, how they want to settle their relationships. Little is known that can guide clinicians about the impact of that editing.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this review was the paucity of research that focused on the effects of DT on family members. Additionally, this review could be incomplete despite effort to ensure its completeness due to factors such as publication bias and our use of only the PubMed database.

Conclusion

Findings from this systematic review identify the need to conduct further adequately powered research related to the feasibility, acceptability, and effects of DT for family members. Future research should focus on understanding whether and how family members benefit from receiving the legacy document and if the timing and manner of family member involvement plays a role in the impact of DT. This could have significant impact on how family members live toward the end of a family member’s illness and during and following bereavement.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by Grant Number 5R01CA200867 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI or NINR. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy.

References

- 1. [Accessed March 21, 2018];Dignity in Care. 2016 http://www.dignityincare.ca/en/

- 2.Fitchett G, Emanuel L, Handzo G, Boyken L, Wilkie DJ. Care of the human spirit and the role of dignity therapy: a systematic review of dignity therapy research. BMC palliative care. 2015;14:8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EndNote X7.5. Thomson Reuters ISI PeopleSoft. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoun SM, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ. Dignity therapy for people with motor neuron disease and their family caregivers: a feasibility study. Journal of palliative medicine. 2015;18(1):31–37. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley B, O'Connor M, Breen LJ, Kane R. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease. BMC palliative care. 2014;13(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chochinov HM, Cann B, Cullihall K, et al. Dignity therapy: a feasibility study of elders in long-term care. Palliative & supportive care. 2012;10(1):3–15. doi: 10.1017/S1478951511000538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johns SA. Translating dignity therapy into practice: effects and lessons learned. Omega. 2013;67(1–2):135–145. doi: 10.2190/OM.67.1-2.p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClement S, Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: family member perspectives. Journal of palliative medicine. 2007;10(5):1076–1082. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goddard C, Speck P, Martin P, Hall S. Dignity therapy for older people in care homes: a qualitative study of the views of residents and recipients of 'generativity' documents. Journal of advanced nursing. 2013;69(1):122–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall S, Goddard C, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. "It makes you feel that somebody is out there caring": a qualitative study of intervention and control participants' perceptions of the benefits of taking part in an evaluation of dignity therapy for people with advanced cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2013;45(4):712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care--a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. Jama. 2002;287(17):2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall S, Goddard C, Martin P, Opio D, Speck P. Exploring the impact of dignity therapy on distressed patients with advanced cancer: three case studies. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(8):1748–1752. doi: 10.1002/pon.3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentley B, O'Connor M, Kane R, Breen LJ. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e96888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(24):5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(8):753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ supportive & palliative care. 2011;1(3):315–321. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montross LP, Meier EA, De Cervantes-Monteith K, Vashistha V, Irwin SA. Hospice staff perspectives on Dignity Therapy. Journal of palliative medicine. 2013;16(9):1118–1120. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vergo MT, Nimeiri H, Mulcahy M, Benson A, Emmanuel L. A feasibility study of dignity therapy in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer actively receiving second-line chemotherapy. The Journal of community and supportive oncology. 2014;12(12):446–453. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho AH, Chan CL, Leung PP, et al. Living and dying with dignity in Chinese society: perspectives of older palliative care patients in Hong Kong. Age and ageing. 2013;42(4):455–461. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avery JD, Savitz AJ. A novel use of dignity therapy. The American journal of psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1340. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubarsky KE, Avery JD. Dignity Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 2016;173(1):90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houmann LJ, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Petersen MA, Groenvold M. A prospective evaluation of Dignity Therapy in advanced cancer patients admitted to palliative care. Palliative medicine. 2014;28(5):448–458. doi: 10.1177/0269216313514883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juliao M. The Efficacy of Dignity Therapy on the Psychological Well-Being in Loved Ones of Terminally Ill Patients. Journal of palliative medicine. 2017;20(11):1182–1183. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall S, Chochinov H, Harding R, Murray S, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. A Phase II randomised controlled trial assessing the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for older people in care homes: study protocol. BMC geriatrics. 2009;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck P, Higginson IJ. Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for older people in care homes: a phase II randomized controlled trial of a brief palliative care psychotherapy. Palliative medicine. 2012;26(5):703–712. doi: 10.1177/0269216311418145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall S, Edmonds P, Harding R, Chochinov H, Higginson IJ. Assessing the feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for people with advanced cancer referred to a hospital-based palliative care team: Study protocol. BMC palliative care. 2009;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho AH, Leung PP, Tse DM, et al. Dignity amidst liminality: healing within suffering among Chinese terminal cancer patients. Death studies. 2013;37(10):953–970. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.703078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]