Abstract

The dual burden of malnutrition (obesity or a non-communicable disease coupled with malnutrition) is prevalent in more than half of all malnourished households that reside in the US. Non-profit organizations should make a conscientious effort to not serve products high in sugar and saturated fat, and low in fiber. Instead, they should diligently serve nutrient-dense foods rich in produce, whole grains and omega 3 fatty acids to minimize health disparities prevalent in LSES households. Nonprofit organizations have the potential to decrease health disparities nationally by feeding health sustaining products such as whole grains, fresh produce and lean proteins. This commentary lists feasible options for organizations to serve healthier options and reduce health disparities such as implementing nutrition policies, capitalizing on donations and securing partnerships.

Keywords: Obesity, Malnutrition, Lower socioeconomic status, Non-profit, Organizations, Youth, Diet, Nutrition, Health disparities

Highlights

-

•

53% of malnourished households in the US have an overweight or obese person.

-

•

Offering calorically-dense, low nutrient food increases disparities in LSES families.

-

•

Non-profit organizations should not serve products high in sugar and low in fiber.

-

•

Non-profit organizations should offer produce, whole grains and omega 3 fatty acids.

-

•

Improving offerings can minimize health disparities among LSES households.

A lack of food access can cause health disparities for those of low socioeconomic status (LSES1). Obesity, for example, disproportionately affects children who grow up with LSES, compared to those with higher socioeconomic status (HSES).2 (Frederick et al., 2014) Similarly, heightened mortality seen among the homeless, can be attributed to an unparalleled rate of ischemic heart disease related to poor diet (Fazel et al., 2014). Both of these are attributes of the dual burden of malnutrition. The dual burden of malnutrition is when obesity occurs alongside malnutrition in the same individual, family or community. In the United States (US), 53% of households with an underweight person, are also housing an overweight or obese person in that same household (Doak et al., 2005).

To address obesity in parallel with food insecurity, organizations must focus on offering nutrient-dense foods (Correia Horvath et al., 2014). The purpose of this commentary is to bring light to the dual burden of malnutrition in the US3 and call organizations to serve healthier foods that facilitate life-sustaining aide for low-income recipients.

1. Collective impact

Over 12% of American households were food insecure in 2016 (USDA, 2018). There are more than 60,000 food pantries and 344,894 churches, many of which offer feeding programs in their communities (American Religious Data, 1952–2010). Equally impactful, youth-serving organizations serve more than 10 million children, many of which offer food to supplement meals served at home (America After 3PM: Afterschool Programs in Demand, 2014).

Utilizing non-profit organizations to increase nutrient-dense food availability is a viable option to reduce both obesity and malnutrition attributed to food insecurity.

2. The burden

The World Health Organization acknowledges that the US has unprecedented rates of both obesity (greater than 1/3 of all adults) and food insecurity (about 1/8 of the population) (Delivering food and services, 2018; NHANES - National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Homepage, 2017). Those living in LSES neighborhoods are most vulnerable to health disparities including but not limited to, coronary artery disease, and often have the least access to care (Organization WH, 2017; Franks et al., 2011).

“Social justice… affects the way people live, their consequent chance of illness, and their risk of premature death. We watch in wonder as life expectancy and good health continue to increase in parts of the world and in alarm as they fail to improve in others”(Organization WH, 2017).

While trying to eradicate malnutrition is noble, we must strategically work with health disparities in mind. Overfeeding calorically-dense, but low nutrient meals exasperates the dual burden of malnutrition and ultimately increases obesity rates and health disparities in low-income populations. Food has the capability to turn disparities towards health. Whole grains, fruits and vegetables supply more fiber than refined grains and are protective against heart disease (Franks et al., 2011; Hung et al., 2004). Protein options such as nuts, beans and legumes are protective against cardiovascular disease and diabetes, both of which are health disparities among the LSES population (Blekkenhorst et al., 2018; El Bilbeisi et al., 2017; Goshtasebi et al., 2018).

Feeding children nutrient-dense foods can be challenging, given that they need to be introduced to a food up to 17 times before accepting it (Carruth et al., 2004). Therefore, organizations may experience waste when introducing new foods to children who have never experienced them. However, federal policies such as the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program have exposed more children to nutrient-dense foods and therefore these foods are accepted earlier (Olsho et al., 2015).

3. Solution

Addressing the dual burden of malnutrition requires a shift in thinking from the quantity of people served to the quality of food served and the impact on individuals. Currently, agencies commonly measure success by quantifying the people or meals served (Weinfield et al., 2014). Health improvements could occur in LSES households if organizations focused on the quality of food, rather than quantity of people who felt full. For example, a food bank in Washington DC prides themselves in “providing good, healthy foods that contribute to wellness” (https://www.capitalareafoodbank.org/food-donation-faqs/, 2018). They proudly display how many families have access to healthy food.

To nourish LSES households, nutrient-dense foods such as fruits, vegetables, and heart healthy omega 3 fatty acids should be readily available. These foods are protective against prevalent diseases and currently under-consumed among the LSES population (Dubowitz et al., 2008).

3.1. Implement nutrition policies (Pescud et al., 2018)

Although half of food banks nationally have enacted nutrition policies, less than 1/3 of these polices eliminate sugary food products from their inventories (Campbell et al., 2013).

One food bank wrote about no longer accepting candy, soda, and sheet cakes. “Food banks do not exist to… reduce food waste, but to address hunger in the communities they serve” (Cueller, 2018). Anotherfood bank interviewed participants regarding what foods should replace sugary sweets. Recipients said they were interested in fresh produce and healthy staples (Kappagoda, 2018).

Refusing donations to collect healthier products is controversial (Chapnick et al., 2017). Having streamlined policies in place can help minimize refusals and empower volunteers to redirect less-beneficial donations (De Boeck et al., 2017). This provides much needed guidance for those volunteering and for those donating food. Including stakeholders and volunteers in policy development and training is critical for successful implementation. Policies should be incorporated into existing organizational structures to ensure sustainability (Muellmann et al., 2017). Policies should include a list that outlines regularly needed staple foods (Martin et al., 2018). (See Table 2).

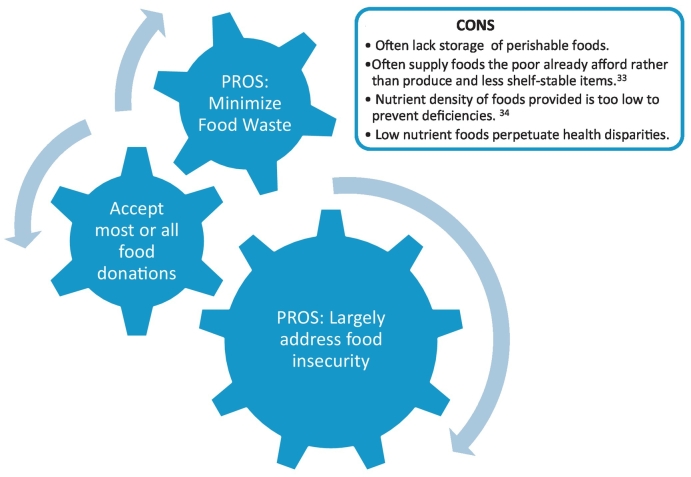

Fig. 1.

Pros and cons of non-profit organizations in the US.

Table 2.

List of food donation staples to add to food policy and distribute to donors.

| To feed beneficial, sustainable, and nutrient-dense foods, donations should include: |

| Fresh or frozen fruit or fruit canned in water or juice (Bowman, 2017) |

| Shelf stable, low-fat dairy (Ozemek et al., 2018) |

| Fresh, frozen and canned low sodium vegetables (Freedman & Fulgoni, 2016; Storey & Anderson, 2018) |

| Whole grains (oatmeal, whole grain pasta, popcorn, brown rice, whole grain bread) (Dinu et al., 2017) |

| Lean proteins (dried or canned beans and lentils, simple meats without added sauces or seasonings) (Ozemek et al., 2018) |

| Omega 3 fatty acids (canned salmon, nut butter, nuts, seeds) (Harris et al., 2018) |

3.2. Capitalize on donations

Many donations consist of food, rather than finances (Tarasuk & Eakin, 2018). This presents an opportunity to ask for higher quality products without additional costs to the organization. For example, asking for produce and nuts can increase the quality of food served, without raising expenses. Additionally, the increase in produce and omega 3 fatty acid consumption can help counteract health disparities in LSES families (Dubowitz et al., 2008).

Refrigeration space is often a concern when transitioning to healthier foods (Chapnick et al., 2017). Organizations should consider grants for safe storage options. Pantries without refrigeration can use shelf-stable, nutrient-dense products such as dried legumes, nuts and seeds, canned produce, and dried whole grains such as brown rice or whole grain pasta.

Using donations to obtain nutrient-dense foods is critical to maintaining a healthful inventory, while sticking to a modest budget.

3.3. Secure partnerships

Gleaning produce from farmers and CSA's has been successful in some areas (Sisson, 2016). Fresh produce from food pantries is the only produce some recipients consume (Dubowitz et al., 2008). Whole foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds are high in soluble and insoluble fibers and low in added sugars; both aspects are protective against cardivascular disease, a common comorbidity of obesity and health disparity in LSES households (Ozemek et al., 2018). (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Evidence-based dietary approaches to eradicating health disparities among LSES households in the United States.

| Diet-related health disparities among the poor in the United States (CDC, 2018) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke and coronary artery disease | Obesity | Poor blood pressure control | Diabetes | |

| Dietary approaches to eradicate disease | Limit sodium, cholesterol, trans and saturated fats. Increase fiber and omega 3 fatty acid intakes. | Limit added sugars, saturated fats, unnecessary snacking. Decrease portion sizes. | Limit sodium, trans and saturated fats. Increase vegetable, fruit, nut, omega 3 rich fatty acid and low-fat dairy consumption | Limit carbohydrate intake to an appropriate amount, spread evenly throughout the day. Eat plenty of legumes and high fiber whole grains. |

| Evidence-based dietary modifications | Consume less: red meat, canned products, processed sugary and salty snacks Consume more: Omega 3 fatty acids, fish, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, nuts, peas, seeds |

Consume less: sugary beverages, sugary candy, high fat proteins, refined grains Consume more: Fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, whole grains, portion controlled meals |

Consume less: red meat, canned food, processed snacks Consume more: Omega 3 fatty acids, fish, fruits and vegetables, lean proteins, whole grains, low-fat dairy, nuts, peas, seeds |

Consume less: sugary beverages, sugary candy, high fat proteins, refined grains Consume more: fruits and vegetables, legumes, lean proteins, whole grains, portion controlled meals |

Additionally, federal resources exist for child and adult care centers through the child and adult care food program (CACFP). In exchange for serving healthier food, meals are federally subsidized. Federal partnerships should be explored as a viable means to serving more nutritious products.

3.4. Nutrition education

Previously, pantries tried to offer healthier alternatives, but recipients have not always known how to prepare some foods given to them. Therefore, recipes and instructions should be included with unprepared foods. Organizations should also consider cooking supplies necessary to prepare foods. Supplying educational tools that accompany healthy options improves the acceptability of nutritious foods and further impacts consumption habits (Sharma et al., 2015).

4. Feasibility

It is notable that such changes are not fast nor easy. However, such improvements are feasible thanks to food pantries and youth-serving organizations who have begun offering healthier foods, implementing policies and securing partnerships (https://www.capitalareafoodbank.org/food-donation-faqs/, 2018; Cueller, 2018). Furthermore, plant-based, lean protein options are more affordable than meat and provide sustainable benefits through increased fiber and protein intakes (Goshtasebi et al., 2018). These cost savings can help balance increased costs from healthier options such as whole grains.

5. Conclusion

The dual burden of malnutrition is prevalent in more than half of all malnourished households that reside in the US. Non-profit organizations should make a conscientious effort to not serve products high in sugar and low in fiber. Instead, they should diligently serve nutrient-dense produce as well as whole grains and foods rich in omega 3 fatty acids to minimize health disparities prevalent in LSES households. Nonprofit organizations have the potential to decrease health disparities nationally by feeding health sustaining products.

Future policies should expand on programs like the CACFP that incentivize offering more nutritious options. Future studies should evaluate the protocol of implementing nutrition policies in non-profit settings.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Authors have no competing interests to declare.

Low socio-economic status

Higher socio-economic status

US = United States

References

- America After 3PM: Afterschool Programs in Demand . 2014. Washington, DC: Afterschool Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- American Religious Data . Bodies AoSoAR. 1952–2010. U.S. religion census. (trans. U.S. Religion Census 1952-20102018) [Google Scholar]

- Bazerghi C., McKay F.H., Dunn M. The role of food banks in addressing food insecurity: a systematic review. J. Community Health. 2016;41(4):732–740. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blekkenhorst L.C., Bondonno C.P., Lewis J.R. Cruciferous and total vegetable intakes are inversely associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in older adult women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018;7(8) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman S.A. Added sugars: definition and estimation in the USDA food patterns equivalents databases. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017;64(1):64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E., Ross M., Webb K. Improving the nutritional quality of emergency food: a study of food bank organizational culture, capacity, and practices. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2013;8(3):261–280. [Google Scholar]

- Carruth B.R., Ziegler P.J., Gordon A., Barr S.I. Prevalence of picky eaters among infants and toddlers and their caregivers' decisions about offering a new food. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004;104(1 Suppl 1):s57–s64. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Health Disparities & Inequalities Report (CHDIR) — Minority Health — CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Chapnick M., Barnidge E., Sawicki M., Elliott M. Healthy options in food pantries—a qualitative analysis of factors affecting the provision of healthy food items in St. Louis, Missouri. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Correia Horvath J.D., Dias de Castro M.L., Kops N., Kruger Malinoski N., Friedman R. Obesity coexists with malnutrition? Adequacy of food consumption by severely obese patients to dietary reference intake recommendations. Nutr. Hosp. 2014;29(2):292–299. doi: 10.3305/nh.2014.29.2.7053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueller S. Food banks reject junk food donations — move for hunger. 2018. https://www.moveforhunger.org/food-banks-reject-junk-food-donations/ (Published 2016. Updated 2016-09-09. Accessed 4/16/2018)

- De Boeck E., Jacxsens L., Goubert H., Uyttendaele M. Ensuring food safety in food donations: case study of the Belgian donation/acceptation chain. Food Res. Int. 2017;100(Pt 2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivering food and services Our network website. 2018. http://www.feedingamerica.org/our-work/food-bank-network.html (Published 2018)

- Dinu M., Pagliai G., Sofi F. A heart-healthy diet: recent insights and practical recommendations. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(10):95. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak C.M., Adair L.S., Bentley M., Monteiro C., Popkin B.M. The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. Int. J. Obes. 2005;29(1):129–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz T., Heron M., Bird C.E. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and fruit and vegetable intake among whites, blacks, and Mexican Americans in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87(6):1883–1891. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bilbeisi A.H., Hosseini S., Djafarian K. Association of dietary patterns with diabetes complications among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza Strip, Palestine: a cross sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2017;36(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0115-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S., Geddes J.R., Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P., Winters P.C., Tancredi D.J., Fiscella K.A. Do changes in traditional coronary heart disease risk factors over time explain the association between socio-economic status and coronary heart disease? BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2011;11:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick C.B., Snellman K., Putnam R.D. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in adolescent obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111(4):1338–1342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321355110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman M.R., Fulgoni V.L. Canned vegetable and fruit consumption is associated with changes in nutrient intake and higher diet quality in children and adults: national health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2010. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016;116(6):940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshtasebi A., Hosseinpour-Niazi S., Mirmiran P., Lamyian M., Moghaddam Banaem L., Azizi F. Pre-pregnancy consumption of starchy vegetables and legumes and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus among Tehranian women. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018;139:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris W.S., Tintle N.L., Etherton M.R., Vasan R.S. Erythrocyte long-chain omega-3 fatty acid levels are inversely associated with mortality and with incident cardiovascular disease: the Framingham heart study. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2018;3:718–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Donation FAQs. 2018. https://www.capitalareafoodbank.org/food-donation-faqs/ Food Donation FAQ Web site. (Accessed 2018, Published)

- Hung H.C., Joshipura K.J., Jiang R. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96(21):1577–1584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappagoda M. Banking on health: improving the inventory at food banks. community commons. 2018. https://www.communitycommons.org/2014/12/banking-on-health-improving-the-inventory-at-food-banks/ (Published 2014. Updated 2014-12-16)

- Martin K.S., Wolff M., Callahan K., Schwartz M.B. Supporting wellness at pantries: development of a nutrition stoplight system for food banks and food pantries. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018;118 doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.03.003. (https://jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672(18)30289-2/fulltext) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muellmann S., Steenbock B., De Cocker K. Views of policy makers and health promotion professionals on factors facilitating implementation and maintenance of interventions and policies promoting physical activity and healthy eating: results of the DEDIPAC project. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):932. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4929-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHANES - National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Homepage . 2017. Prevention CfDCa. (CDC2018) [Google Scholar]

- Olsho L.E., Klerman J.A., Ritchie L., Wakimoto P., Webb K.L., Bartlett S. Increasing child fruit and vegetable intake: findings from the US Department of Agriculture Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015;115(8):1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH . World Health: World Health Organization; 2017. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health — Final Report. (2017-04-25 12:21:57) [Google Scholar]

- Ozemek C., Laddu D.R., Arena R., Lavie C.J. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2018;4:388–393. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescud M., Friel S., Lee A. Extending the paradigm: a policy framework for healthy and equitable eating (HE2) Public Health Nutr. 2018:1–5. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018002082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Helfman L., Albus K., Pomeroy M., Chuang R.J., Markham C. Feasibility and acceptability of brighter bites: a food co-op in schools to increase access, continuity and education of fruits and vegetables among low-income populations. J. Prim. Prev. 2015;36(4):281–286. doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson L.G. Food recovery program at farmers' markets increases access to fresh fruits and vegetables for food insecure individuals. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2016;11(3):337–339. [Google Scholar]

- Storey M., Anderson P. Total fruit and vegetable consumption increases among consumers of frozen fruit and vegetables. Nutrition. 2018;46:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk V., Eakin J. Food assistance through “surplus” food: insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work Springer link. AGR HUM VALUES. 2018;22(2):177–186. [Google Scholar]

- USDA; 2018. USDA ERS - Key Statistics & Graphics. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx Economic Research Service Web site. (Published 2018)

- Weinfield N.S., Mills G., Borger C. 2014. Hunger in America: National Report. Feeding America. [Google Scholar]