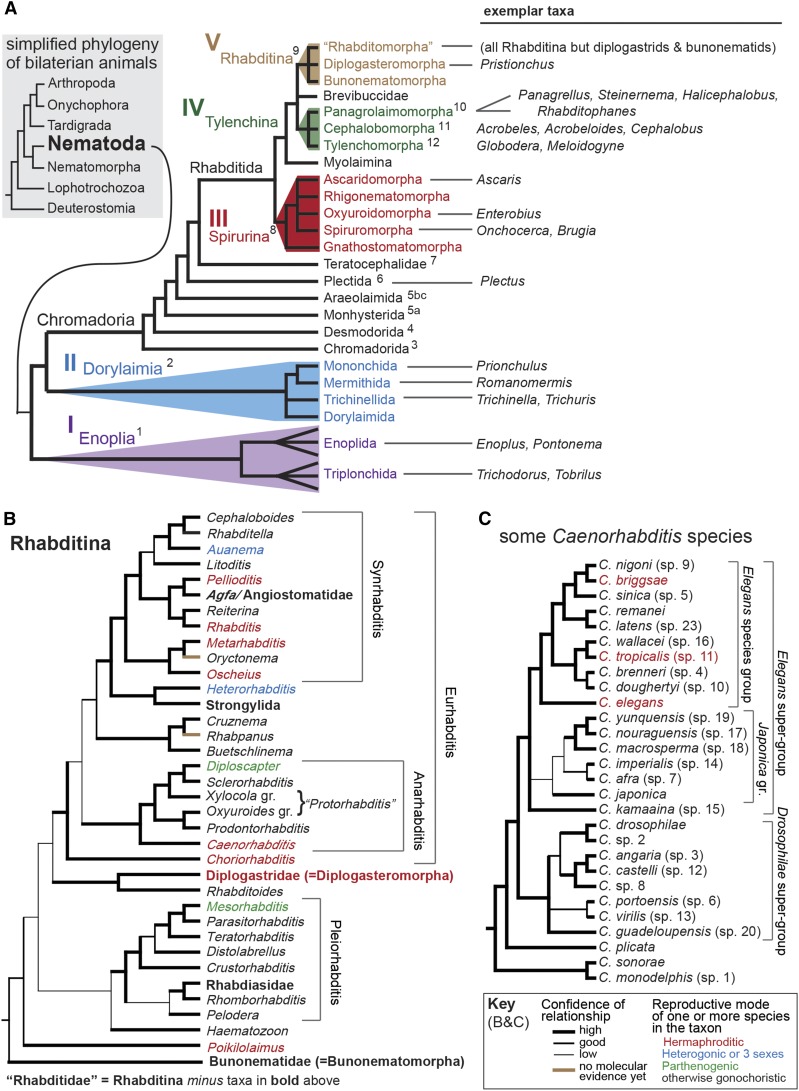

Figure 1.

Phylogenies of phylum Nematoda, suborder Rhabditina, and genus Caenorhabditis, based on molecular data. (A) Inset shows the phylogenetic position of Nematoda within a very simplified phylogeny of bilaterian animals. Recent molecular studies place Nematoda together with its sister group Nematomorpha as the closest relatives of Panarthopoda (Arthropoda, Onychophora, Tardigrada) in a clade often called Ecdysozoa (Giribet 2016; Giribet and Edgecombe 2017). The phylogeny of Nematoda has been derived mainly from ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and contains several well-defined clades: clades I–V (De Ley and Blaxter 2004; De Ley 2006) designated in like-colored roman numerals, taxon names, and polygons; and clades 1–12 designated in black superscripts to corresponding taxon names (Holterman et al. 2008; van Megen et al. 2009). Some taxa have been left out here for simplicity. Taxa other than Rhabditina that are mentioned in this review are listed at the right. Adapted with permission from Blaxter (2011) and Kiontke and Fitch (2013). Taxa in quotation marks are paraphyletic: “Rhabditomorpha” includes all Rhabditina except Diplogasteromorpha and Bunonematomorpha. (B) Phylogeny of Rhabditina (clade V), almost entirely based on molecular data from rRNA and other loci (Kiontke et al. 2007; Ross et al. 2010; Kanzaki et al. 2017). Thickness of the lineages, as indicated in the key at lower right, indicates the approximate level of confidence estimated from statistical tests. The systematics of “Rhabditidae” was recently revised (Sudhaus 2011) based almost entirely on the molecular phylogeny (Kiontke et al. 2007) with some consideration of morphological characters to place taxa only known from literature descriptions (brown lineages). A few, mostly monotypic taxa of uncertain position are not shown. Four named suprageneric clades are shown with brackets. Despite being paraphyletic, “Rhabditidae” is a useful taxon because it includes many free-living (rarely parasitic) species with fairly similar Bauplan and excludes three specialized parasitic taxa (Angiostomatidae/Agfa, Strongylida, Rhabdiasidae) and Diplogastridae, a clade of species morphologically distinguished from “Rhabditidae” that have undergone an extensive adaptive radiation. Pristionchus pacificus and its relatives are included in the Diplogastridae. The “Rhabditidae” sister taxa to each of these special groups provide important resources for investigating the evolutionary origins of parasitism and other specializations that have resulted in adaptive radiations. Colored fonts indicate taxa in which reproductive mode has evolved from gonochorism to hermaphroditism, heterogonism or parthenogenesis (see key at lower right). Taxon names in bold font are at higher levels than the genera otherwise depicted. For more complete information, see RhabditinaDB at rhabditina.org. (C) Phylogeny for some Caenorhabditis species as inferred by molecular data from rRNA and several other loci (Kiontke et al. 2011). Due to the rapid rate of discovery, species are provisionally designated with numbers (sp. n) until names can be attached to these species units (Félix et al. 2014). Only 28 of the ∼50 known species are shown here; however, this phylogeny shows all the major known clades (demarcated here as “species groups”). Several Caenorhabditis species are only known from morphological descriptions and not included here. Hermaphroditic species are indicated in red font; other species are gonochoristic.