Abstract

This paper studies the life-cycle impacts of a widely-emulated high-quality, intensive early childhood program with long-term follow up. The program starts early in life (at 8 weeks of age) and is evaluated by an RCT. There are multiple treatment effects which we summarize through interpretable aggregates. Girls have a greater number of statistically significant treatment effects than boys and effect sizes for them are generally bigger. The source of this difference is worse home environments for girls with greater scope for improvement by the program. Fathers of sons support their families more than fathers of daughters.

Keywords: Gender differences, childcare, early childhood education, randomized trials, substitution bias, J13, I28, C93

1. Introduction

This paper examines impacts by gender of two closely related influential early childhood programs: the Carolina Abecedarian Project (ABC) and its sister program, the Carolina Approach to Responsive Education (CARE), henceforth ABC/CARE. Both were evaluated by the method of random assignment. While specific outcomes of ABC/CARE have been studied previously, our paper is the first to aggregate and summarize all of the reported outcomes to evaluate the program.

ABC/CARE was conducted in Chapel Hill, North Carolina for a sample of children born between 1972 and 1980. This pioneering program focused on improving the early years of disadvantaged children. It is a template for many current and proposed early childhood programs.1 It started at 8 weeks of age and continued through age 5. Treatment and control children were followed through their mid 30s, with data collected on multiple dimensions of human development with over 100 reported program outcomes.2

There are pronounced gender differences in the treatment effects of ABC/CARE. To avoid cherry-picking, we analyze aggregates of treatment effects as reported in Table 1. The aggregates are constructed by counting the proportion of outcomes by category for which male mean treatment effects for items in a category equal or exceed female treatment effects. To understand the entries to the table, consider the row for the outcome “employment.” In the control group, all mean outcomes are larger for males compared to females. This is denoted by the fraction 1.000. In the table, we also report an exact, non-parametric test of the null hypothesis that the distribution of employment outcomes in the control group is the same for males and females. The p-value associated with the test is 0.117.3 The comparable statistics for the treatment group are 0.75 and a p-value of 0.080, respectively.

Table 1:

Summary of Gender Differences in Outcome Aggregates

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | # Outcomes | Control |

Treatment |

Treatment - Control |

Overall |

||

| Proportion Male > Female | H0: Male = Female p-value | Proportion Male > Female | H0: Male = Female p-value | [5] - [3] | H0: Male = Female p-value | ||

| IQ | 15 | 0.733 | 0.290 | 0.533 | 0.228 | −0.200 | 0.000 |

| Achievement | 12 | 0.833 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 0.341 | −0.833 | 0.303 |

| Socio-Emotional | 22 | 0.455 | 0.191 | 0.364 | 0.599 | −0.091 | 0.165 |

| Parenting | 7 | 0.571 | 0.977 | 0.286 | 0.142 | −0.286 | 0.477 |

| Parental Income | 8 | 0.750 | 0.290 | 0.875 | 0.230 | 0.125 | 0.076 |

| Education | 9 | 0.667 | 0.191 | 0.111 | 0.142 | −0.556 | 0.076 |

| Employment | 4 | 1.000 | 0.117 | 0.750 | 0.080 | −0.250 | 0.030 |

| Crime | 4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Risky Behavior | 5 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.200 | 0.080 | −0.200 | 0.000 |

| Health | 22 | 0.545 | 0.003 | 0.545 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Mental Health | 11 | 0.818 | 0.191 | 0.545 | 0.599 | −0.273 | 0.165 |

Note: Column [1] lists the outcome category. The specific outcomes in each category are listed in Appendix B. Column [2] lists the number of outcomes observed within each category. Column [3] lists the proportion of outcomes for which the average for males is greater than the average for females for the control group. 1.000 denotes that all mean outcomes across category are greater for males than for females. 0.000 denotes the opposite. A proportion is bold when it statistically significantly differs from 0.50 at the 10% level, so both 1.000 and 0.000 could be statistically significant. The relevant null hypothesis is 0.50 at which point neither males nor females outperform the other. For inference, we use the Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing the proportions over 1,000 bootstraps. For bootstrap b ∈ [1,…, 1000] we compute the proportion of variables in each outcome category for which the male average is greater than the female average and obtain a non-parametric p-value from this procedure. Column [4] displays the p-value for an exact, non-parametric test due to Rosenbaum (2005) for the null hypothesis that the joint distribution of the outcomes within each category is the same for males and females in the control group. Column [5] is analogous to column [3] for the treatment group. Column [6] is analogous to column [4] for the treatment group. Column [7] is the difference between columns [5] and [3] and the inference procedure is analogous to that in column [3]. Column [8] is analogous to column [4] but performs an exact test across genders pooling the control and treatment groups.

Treatment reduces gaps in these aggregates between males and females. The difference between the male-female gap for treatments and the male-female gap for controls is 0.25. We decisively reject the null of equality of the pooled male and pooled female distributions. This pattern holds generally for the outcomes that we study.4 Females benefit more than males from treatment, which reduces the male-female gaps in the controls. However, males also benefit substantially from the program.

Differential treatment effects by gender arise because control-group girls grow up in less favorable environments compared to control-group boys. Specifically, in the homes of girls, fewer fathers are present and maternal human capital is lower. Girls in the control group who stay at home (27% of the control-group girls), were raised in more disadvantaged environments. Girls in the control group who went to preschools other than ABC/CARE (73% of the control-group girls), likely went to lower-quality preschools. Their families were more resource constrained compared to their male counterparts for whom more fathers are present.5 Girls benefited more from treatment because without it they would have grown up in more disadvantaged environments.6

Parents of the controls in ABC/CARE had the option of keeping their children at home or sending them to daycare facilities other than ABC/CARE. There is an important difference in the take-up of alternatives by the gender of controls. Among control-group girls, those from more disadvantaged families stay at home. Among control-group boys, the more advantaged stay at home instead of attending lower-quality alternative childcare. Boys benefit more from participating in ABC/CARE when compared to attending alternative preschools because of their relatively better home environments. Girls benefit more from ABC/CARE when compared to home-based care because those who stay at home are more disadvantaged.

A companion paper, García et al. (2018), presents a cost-benefit analysis of ABC/CARE that monetizes program treatment effects. While a greater number of statistically significant treatment effects is found for girls, the monetized values of these effects are greater for boys. Untreated boys can do more costly harm, which the program prevents.

This paper unfolds in the following way. Section 2 describes the experimental data we analyze. We document the take-up of alternative out-of-home childcare attended by many control-group subjects. Section 3 defines the treatment effects we estimate and how we summarize them. Section 4 reports the treatment effects overall and by gender. We show sharp gender differences for many categories of outcomes. Section 5 discusses the sources of these differences. Section 6 summarizes and places our analysis in the context of a broader literature.

2. Data

We analyze a combined sample of the two closely related programs: ABC and CARE. Table 2 summarizes their main features. Both interventions were implemented by researchers at the Frank Porter Graham Center (FPG) at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, and targeted children from disadvantaged families in the Chapel Hill area. ABC had four cohorts born between 1972 and 1977, and CARE had two cohorts born between 1978 and 1980. Eligibility was determined on the basis of a High Risk Index (HRI) developed for ABC and adapted for CARE (Ramey and Smith, 1977; Wasik et al., 1990). Components of the HRI include father’s presence, parental employment, and participation in welfare.7 Based on these eligibility requirements, García et al. (2018) calculate that 43% of African Americans were eligible during the period of intervention and that 19% of all African American children are eligible now.

Table 2:

Overview of the ABC and CARE Programs

| Site | Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

| Cohorts | 4 (ABC), 2 (CARE) |

| N | 58 treatment, 56 control (ABC) |

| 17 treatment, 23 control (CARE) | |

| Eligibility | High Risk Index (HRI) > 11 |

| Biologically healthy | |

| Treatment years | 1972–1981 (ABC), 1977–1983 (CARE) |

| Treatment duration | 5 years |

| Home visits | 2.5–2.7 per month (CARE) |

| Center care | 50 weeks per year |

| 30–45 hours per week | |

| Other treatment components | Formula until 6 months |

| Diapers until 6 months | |

| Health check-ups | |

| Medical care | |

| Parenting instruction | |

| Counseling | |

| Transportation to center | |

| Control-group incentives | Formula until 6 months |

| Diapers until 6 months | |

| Health check-ups until 1 year (ABC, cohort 1) | |

| Adult-child ratio | 1:3–1:6 |

| Teacher requirements | High school through masters |

| Experience with children | |

| Specialists | Physician, nurse, social worker |

Note: Biologically healthy includes lack of serious illness, including mental retardation.

Sources: Ramey et al. (1976); Ramey and Smith (1977); Ramey et al. (1985); Wasik et al. (1990); Ramey and Campbell (1991).

Both interventions involved intensive center-based care for subjects in the treatment group starting at 8 weeks and continuing until age 5 before the children started kindergarten. In addition to free access to this center-based care, treatment-group subjects also received daily health screenings, diapers, and formula for 6 months. Control-group families received diapers and formula as well for the same period of time.8 Between ages 5 and 8, there was an additional component of treatment with home visits to tutor the children and to encourage families to be involved in their child’s schooling. In CARE, all the subjects who received center-based care also received this school-age component. In ABC, treatment status of this component was randomized. We do not analyze the post-5 home-based visits because previous work has found that this component of treatment has no statistically significant impact (Campbell et al., 2002, 2014).

The program focused on developing language, cognition, and social-emotional skills.9 Program curricula emphasized child-led learning of skills important for future learning (Ramey and Smith, 1977; Wasik et al., 1990; Ramey and Campbell, 1991). The teachers and classroom aides were trained throughout the intervention. Researchers and child development experts at FPG observed classroom interactions and gave detailed feedback to the instructors (Ramey et al., 2012).10

CARE included an additional arm of treatment. Besides the services offered in ABC, those in the CARE treatment group also received home visiting from birth to age 5. Home visiting consisted of biweekly visits focusing on improving parental problem-solving skills. To test the effectiveness of this home-visiting component, there was a third randomized group (N = 23) that received only the home visiting component at ages 0-5, but not center-based care (Wasik et al., 1990). In light of previous analyses of CARE finding no effect of the early-age home-visiting component, we drop this last group from our analysis.11 These analyses justify merging the treatment groups of ABC and CARE. We henceforth analyze the samples as coming from a single ABC/CARE program.

Table 3 compares pre-program variables for experimental and gender groups. The only marginally statistically significant difference in baseline variables between boys and girls is in the HRI score, which is 1.78 points lower for males than for females, consistent with their better home environments. A higher HRI is associated with greater disadvantage.

Table 3:

Baseline Differences, ABC/CARE

| Variable | Female Mean | Male Differential | p-value | Control Mean | Treatment Differential | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 19.72 | 1.13 | 0.15 | 20.52 | −0.51 | 0.51 |

| Mother works | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

| Mother’s IQ | 84.46 | 1.33 | 0.46 | 84.65 | 0.98 | 0.58 |

| Father at home | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.29 | −0.05 | 0.51 |

| Number of siblings | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.67 | 0.71 | −0.18 | 0.29 |

| HRI score | 21.57 | −1.78 | 0.06 | 21.39 | −1.47 | 0.13 |

| Apgar score, 1 min. | 7.68 | −0.07 | 0.80 | 7.60 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| Apgar score, 5 min. | 8.94 | −0.20 | 0.33 | 8.87 | −0.04 | 0.83 |

| Birthweight | 7.18 | −0.20 | 0.34 | 7.17 | −0.19 | 0.38 |

| Gestational age | 39.85 | −0.42 | 0.27 | 39.87 | −0.50 | 0.19 |

Note: The variables in this table are all measured at baseline, close to when the children were born. Maternal labor supply (“Mother works”) is represented using an indicator variable. A larger HRI (High Risk Index) score indicates more disadvantage. Apgar, measured at 1 and 5 minutes after birth, is a test of the health condition of newborn babies. A score closer to 10 indicates a healthier condition (Apgar, 1966). Birthweight is in pounds and gestational age is in weeks. Control means and treatment differentials pool males and females.

2.1. The Randomization Protocol

Randomization for ABC/CARE was conducted on child pairs matched on family background. Siblings and twins were jointly randomized into either treatment or control groups. For siblings, this only occurred when two siblings were close enough in age so that both of them were eligible for the program. Pairing was based on the High Risk Index, as well as maternal education, maternal age, and gender of the subject.12

ABC collected an initial sample of 121 subjects. All providers of health care and social services (referral agencies) in the area of the ABC/CARE study were informed of the programs. They referred mothers whom they considered disadvantaged. Eligibility was corroborated before randomization. Encouragement from the referral agencies was such that all but one of the referred mothers agreed to participate in the initial randomization.13 We discuss the pattern of missing observations in Appendix A.3. In Appendix D.3, we document that our estimates are robust when we adjust for missing data using standard weighting methods described in Appendix B.2.

Twenty-two subjects in ABC did not stay in the program through age 5. The number of dropouts is evenly balanced across treatments and controls. Dropping out was primarily related to the health of the child and the mobility of families rather than as a result of dissatisfaction with the program. The 22 dropouts include four children who died, four children who left the study because their parents moved, and two children who were diagnosed as developmentally delayed.14 Details are in Table A.2. Everyone offered the program was randomized to either treatment or control. Dropping out occured after randomization and was balanced across treatment groups. We conduct the same analysis for the CARE sample, although there were far fewer dropouts and no compromised randomization.15

2.2. Control Group Substitution

In ABC/CARE, many control-group subjects (but no treatment-group subjects) attended alternative center-based care.16 The figure is 75% for ABC and 74% for CARE. This information comes from a survey administered to ABC/CARE families asking about the childcare arrangements made during each month between birth and age 5. Home care includes parental care, as well as care of a relative, neighbor, or friend. The survey also captured specifics, such as the name of the center-based institutions, allowing for a detailed understanding of alternative care environments.

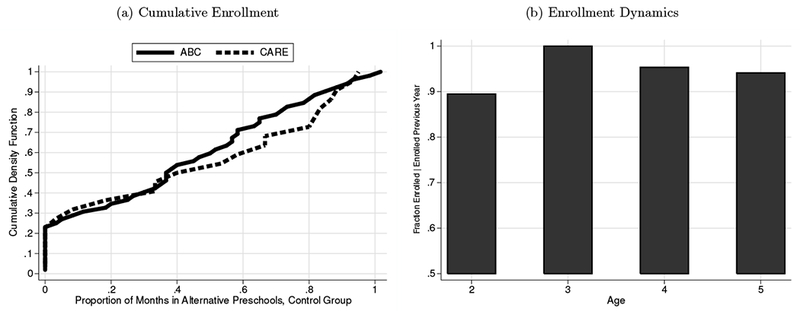

Figure 1a shows the cumulative distribution of the proportion of time in the first five years that control subjects were enrolled in alternative formal childcare programs. Figure 1b shows the dynamics of enrollment. Those who enrolled generally stay enrolled over time. As control-group children aged, they were more likely to enter childcare.17

Figure 1:

Control Substitution Characteristics, ABC/CARE Control Group

Note: Panel (a) displays the cumulative distribution function of enrollment in alternatives. Panel (b) displays the fraction of ABC/CARE control-group children enrolled in alternatives, conditional on being enrolled in the previous age (at least one month).

As a group, the children in the control group who enroll in alternative early childcare programs are less economically disadvantaged at baseline compared to children who stay at home, although, as we show below, there are important differences by gender of the child. Disadvantage is measured by maternal education, maternal IQ, Apgar scores, and the High Risk Index that defines ABC/CARE eligibility. Control children who attend alternative formal care generally have fewer siblings. On average, they are children of mothers who are more likely to be working at baseline (statistically significant at 10%). Parents of girls are much more likely to use alternative center childcare if assigned to the control group.

Table A.4 tests differences across these variables between children in the control group who attended and those who did not attend alternative childcare. The only statistically significant difference in observed baseline characteristics between the controls who use formal childcare and those who stay at home is whether the mother works. The mother is more likely to work at baseline for children attending alternative care. We discuss selection into alternative care settings by gender of the child in Section 5.

While most of the alternative childcare centers received federal subsidies and were subject to the federal regulations of the era, they were relatively low-quality compared to ABC/CARE (Burchinal et al., 1989). In terms of child-staff ratios, ABC/CARE far exceeded the highest state and federal standards of the day.18 We do not have baseline information on the quality of the parent-child interaction to be able to precisely analyze the environments of those who stayed at home.

When we compare ABC/CARE treatment to that from alternative preschools, ABC/CARE produces substantial treatment effects. Parents perceived that ABC/CARE was superior to alternative preschools because all offered it chose to participate in it. The access of control-group children to alternative programs creates both a problem of substitution bias and an opportunity to learn about the benefits or harms of lower-quality childcare arrangements. Exploiting the heterogeneous experiences of the control-group subjects, we isolate the effects of developmentally enriched environments compared to home environments, and the effects of lower-quality center environments compared to home environments for boys and girls.

2.3. Data Collection

Measures of cognitive, social-emotional, and parenting skills were collected during the intervention and while the subjects were in school.19 The researchers collected information on the subjects’ academic performance including grade retention and special education. The adult surveys (at ages 21 and 30) cover items related to employment, post-secondary education, health, criminal activity, and family structure. When the subjects were in their mid 30s, the researchers collected administrative crime data and conducted a full medical survey. Appendix D describes the data that we use more completely.

3. Parameters of Interest

Random assignment to treatment does not guarantee that conventional treatment effect estimators answer policy-relevant questions. We define and estimate three parameters that address different policy questions. Let W = 1 indicate that the parents referred to the program participate in the randomization protocol. W = 0 indicates otherwise. R indicates randomization into the treatment group (R = 1) or to the control group (R = 0). D indicates participation in the program, i.e., D = R implies compliance with the initial randomization protocol.

Individuals are eligible to participate in the program if baseline background variables . is the set of scores on the risk index that determines program eligibility. Because all of the eligible people given the option to participate choose to do so (W = 1 and D = R), we can safely interpret the treatment effects generated by the experiment as average treatment effects for the population for which and not just treatment effects for the treated.20

Let be the outcome j for the treated, and be the control counterfactual. depends on the exposure to various alternative preschools while ABC/CARE was active (i.e., it depends on the degree of control substitution).21 The index set for the outcomes is , which we can partition by outcome category ( with and indexes categories).

All treatment-group children had the same exposure to the ABC/CARE treatment and no exposure to alternative center-based care.22 It would be desirable to identify and estimate parameters evaluating ABC/CARE against all possible levels of exposure to alternative preschools, but our samples are too small to credibly do so. We simplify the analysis of the counterfactual to ABC/CARE by creating two categories. “H” indicates that the control-group child stays at home throughout the entire length of the program. “C” indicates that a control-group child is in alternative center childcare for any amount of time.23 We thus compress a complex reality into two counterfactual outcome states for each outcome j:

One parameter of interest addresses the question: What is the effect of the program as implemented? This is the effect of the program compared to the next best alternative as perceived by the parents (or the relevant decision maker) and is defined by

| (1) |

where the second equality follows because everyone who was eligible elected to participate in the program. For the sample of eligible people, this parameter addresses the effectiveness of the program relative to the perceived best (by the agent) quality of all available alternatives when the program was implemented, including staying at home. This is the Local Average Treatment Effect (LATE).24

We define V as a dummy variable indicating that the control-group child attended alternative center-based childcare. V = 0 denotes that the control-group child stayed at home. The outcome when a child is in the control group is

| (2) |

It is fruitful to assess the effectiveness of the program compared to a condition in which the child stays at home full time. The associated causal parameter is:

| (3) |

It is also useful to assess the average effectiveness of a program relative to attending an alternative preschool with associated causal parameter:

| (4) |

“Fix V” means V is fixed to the designated value.25

Random assignment to treatment does not directly identify the parameters in Equations (3) or (4). Econometric methods are required. In this paper, we rely on matching to control for selection into home or an alternative preschool by the control group. We assume that observed characteristics are sufficient to describe the selection into alternative center-based arrangements. In Appendix D, we show the balance across the groups in the matched samples along the observed selection variables (e.g., family characteristics, Apgar scores, gender), further justifying this approach.26

We report estimates from alternative empirical strategies, including instrumental variables and control functions, in Appendix E. The estimates from these alternative estimation strategies are consistent with results from matching but lack precision. Appendix D.13.1 displays results with alternative definitions of V (i.e., different thresholds define if a child attended alternative preschool). The results are robust to the various definitions. What matters is whether any center-based child care is being used (V > 0)—not the specific exposure time above a zero value.

3.1. Summarizing Multiple Treatment Effects

The extensive data for ABC/CARE generate many outcomes that we can use to evaluate the program. Summarizing these effects in an interpretable way is challenging.27 We present effect sizes averaged over outcomes. We also construct combining functions that count the proportion of treatment effects that are positive for different categories of outcomes. In a similar fashion, we study the count of the proportion of treatment effects that are positive and statistically significant at the 10% level. We complement these analyses by applying an exact non-parametric test on the equality of the distributions of outcomes across treatment groups developed in Rosenbaum (2005).

Combining Functions.

Consider a block of outcomes , ℓ ∈ {1,…, L}, with cardinality Dℓ, and associated treatment effects Δ1,… ΔDℓ. We assume that outcomes can be ordered so that Δj > 0 is beneficial.28 The count of positive treatment effects within block is:

| (5) |

The proportion of beneficial outcomes, our combining function, is Cℓ/Dℓ. In our empirical analysis we consider the outcomes as a block. Different blocks are grouped by common categories (e.g., employment, health, crime).

Under the null hypothesis of no treatment effect for the block of outcomes indexed by and assuming the validity of asymptotic approximations, the mean of Cℓ/Dℓ is centered at .29 We compute the fraction Cℓ/Dℓ and the corresponding bootstrapped empirical distribution to obtain a p-value. The bootstrap procedure accounts for dependence in unobservables across outcomes (within blocks) in a general way.

A test based on the number of outcomes for which the treatment effect is statistically significant at the 10% level produces similar inference. Under the null hypothesis, 10% of all outcomes should be “significant” at the 10% level even if there is no treatment effect of the program.30 The combining functions avoid: (i) arbitrarily picking outcomes that have statistically significant effects—“cherry picking”; or (ii) arbitrarily selecting blocks of outcomes to correct the p-values when accounting for multiple hypothesis testing. We present p-values for these hypotheses and a number of combining functions by outcome category in Appendix D.31

An Exact Non-Parametric Test.

We also test for equality of treatment and control distributions by outcome using an exact test developed by Rosenbaum (2005). We provide a brief explanation of the test and refer interested readers to the original source for more details. Let index the individuals in our sample and consider the block of outcomes . Let dij be the distance between the individuals i, j ∈ , i ≠ j, based on the outcomes in . In our application, this is the Mahalanobis distance.32 There is an optimal non-bipartite pairing of individuals according to dij.33 This is obtained by minimizing the distance across all possible pairings i,i′ in the sample.

Under the null hypothesis of no treatment effects, pairings of treatment-group children with control-group children should be as frequent as pairings of treatment-group children with other treatment-group children and control-group children with other control-group children. If a relatively large number of pairs are matched equally across groups using this metric, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that the joint distribution of outcomes in block , ℓ ∈ {1,…, L} is the same across the treatment and control groups.

The number of treatment-control pairings in the optimal non-bipartite pairing within the block of outcomes , denoted by Aℓ, ℓ ∈ {1,…, L}, is a summary statistic allowing us to test the null hypothesis of interest. Its exact p-value can be calculated. Asymptotically, the studentized value of Aℓ follows a standard normal distribution. For each block, we present these asymptotic p-values to complement the information provided by the combining functions.34

4. Estimates and Tests of Differences in Treatment Effects

This section presents our estimates of treatment effects by gender. We categorize outcomes and present estimates of treatment effects pooled within each category. Treatment effects for individual outcome variables are listed in Appendix D.

Table 4 aggregates treatment effects across all ages and within categories. The benefits of treatment are noticeable for both males and females. Benefits appear across the life cycle and across multiple outcomes. Participants in ABC/CARE benefit in terms of both cognitive and socio-emotional skills. They also benefit in terms of scores on achievement tests, which help measure both cognitive and non-cognitive skills.35 These estimates reveal a clear female advantage in the program’s effect on skill development.

Table 4:

Combining Functions and Exact Non-Parametric Tests

| Average Effect Size | % > 0 Treatment Effect | % > 0, Significant Treatment Effect | Rosenbaum (2005) p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IQ | ||||

| Females | 0.719 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 0.046 |

| Males | 0.664 | 100.000 | 85.714 | 0.045 |

| Achievement | ||||

| Females | 0.672 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 0.046 |

| Males | 0.235 | 100.000 | 40.000 | 0.086 |

| Social-emotional | ||||

| Females | 0.385 | 92.857 | 71.429 | 0.235 |

| Males | 0.059 | 50.000 | 21.429 | 0.147 |

| Parental Income | ||||

| Females | 0.283 | 100.000 | 37.500 | 0.086 |

| Males | 0.157 | 100.000 | 25.000 | 0.147 |

| Parenting | ||||

| Females | 0.274 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 0.602 |

| Males | 0.060 | 80.000 | 0.000 | 0.147 |

| Education | ||||

| Females | 0.356 | 83.333 | 66.667 | 0.000 |

| Males | 0.174 | 83.333 | 16.667 | 0.235 |

| Employment | ||||

| Females | 0.200 | 100.000 | 50.000 | 0.151 |

| Males | 0.438 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 0.022 |

| Crime | ||||

| Females | 0.242 | 100.000 | 100.000 | 0.715 |

| Males | −0.093 | 33.333 | 0.000 | 0.812 |

| Risky Behavior | ||||

| Females | 0.099 | 100.000 | 0.000 | 0.469 |

| Males | 0.011 | 25.000 | 25.000 | 0.086 |

| Health | ||||

| Females | 0.060 | 68.750 | 6.250 | 0.046 |

| Males | 0.061 | 73.333 | 420.000 | 0.000 |

Note: This table displays summaries of treatment effects by outcome category and gender. Each of the panels contains statistics calculated using outcomes grouped by category. The average effect size is calculated by averaging over the effect size of the outcomes in the outcome category. The effect sizes of the individual outcomes are calculated by dividing the treatment-control mean difference by the standard deviation of the control group. We present bootstrapped p-values. For the proportion of outcomes that are positive and significant, we do a “double bootstrap” procedure. The null hypothesis for the average effect sizes is that they are 0. The null hypothesis for the proportion of outcomes that are (significantly) positive is that they are (10%) 50%. The Rosenbaum (2005) p-value tests the null of equality of pooled outcome treatment and control distributions within each category. For computational simplicity, we approximate the exact p-values using asymptotic p-values. Rosenbaum (2005) presents several simulation exercises showing that the validity of this approximation. Statistics significant at the 0.10 level are bolded.

ABC/CARE offered full-day child care for participants and thus facilitated maternal employment and education.36 The program has a sizable effect on education. The effect size is 0.356 for females — about twice that for males, 0.174. The program enhanced parental income. The program enhanced parenting as measured by HOME scores for children and their mothers between ages 0 and 8.37 The effect size on parenting for boys is smaller than that for girls (0.06 vs. 0.274), in part due to the fact that the HOME measurement depends on punishment and boys are more likely to be punished than girls. The families of boys scored lower in this dimension than the families of girls.

In outcomes like education, employment, crime, risky behavior (which includes, for example, drug use) there are also sizable treatment effects. A companion paper, García et al. (2018), finds that monetized versions of these treatment effects translate into a benefit/cost ratio of 7.3. This estimate accounts for the costs of implementing the program, including the welfare loss generated by taxing society in order to fund the program.38

Consistent with the results in Table 1, the results in Table 4 show that females generally benefit more from treatment compared to males. In 8 out of the 10 categories that we consider, the within-category average effect size is larger for females. In 9 out of 10 categories, the proportion of positive effects is at least as large for females compared to that of males. We next drill down on gender differences.

In 7 out of 10 categories, the percentage of treatment effects that are statistically significant at the 10% level is greater for women.

Pooling outcomes within categories we test equality of treatment and control distributions for each gender using a test due to Rosenbaum (2005). We find statistically significant differences for both genders. There is evidence of treatment effects for both males and females on IQ, achievement tests, and health. Effects on parental income are only statistically significant for the parents of girls, as are the effects of education.39 The opposite pattern is found for boys on employment and risky behavior.40

5. Explaining Gender Differences

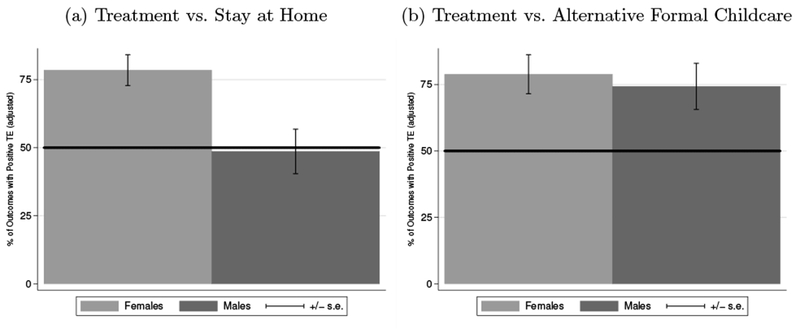

We have established that there are pronounced gender differences in the patterns of positive and statistically significant treatment effects.41 Figure 2 reports the estimated combining functions by gender and by category of care used by the control group.42

Figure 2:

Positively Impacted Outcomes, ABC/CARE Males and Females

Note: Panel (a) displays the percentage of positive treatment effects in accordance with the parameter in Equation (3)—treatment vs. staying at home—by gender. Panel (b) is analogous for Equation (4)—treatment vs. alternative formal childcare. Standard errors are based on the empirical bootstrap distribution. The null hypothesis is that the proportions of positive treatment effects are greater than 50%. For a full list of the estimated combining functions, see Appendix D.

The null hypothesis of no treatment effect is equivalent to the hypothesis that the proportion of outcomes favoring men is equal to 0.500. Figure 2a displays the proportion of positive treatment effects comparing outcomes of the treated to outcomes for those who stay at home. Figure 2b is the counterpart of Figure 2a and displays analogous combining functions comparing treatment effects of those participating in ABC/CARE to those who attend alternative formal childcare. These estimates account for selection into the mode of childcare using matching.

Comparing ABC/CARE to those who stay at home (Figure 2a), a greater proportion of the treatment effects is positive for women than for men. While the female proportion is statistically significantly larger than 0.500, the male proportion is not. Figure 2b shows a different pattern when we compare outcomes from ABC/CARE with outcomes of those who attended alternative formal childcare. Close to 75% of the treatment effects are positive for men. For women, the proportion of positive treatment effects is similar to the proportion obtained from comparing ABC/CARE to those who stay at home. From this analysis, we conclude that ABC/CARE was effective for men compared to alternative formal childcare programs, but not when compared to staying at home. ABC/CARE was effective for women regardless of the mode of childcare used by the controls.43

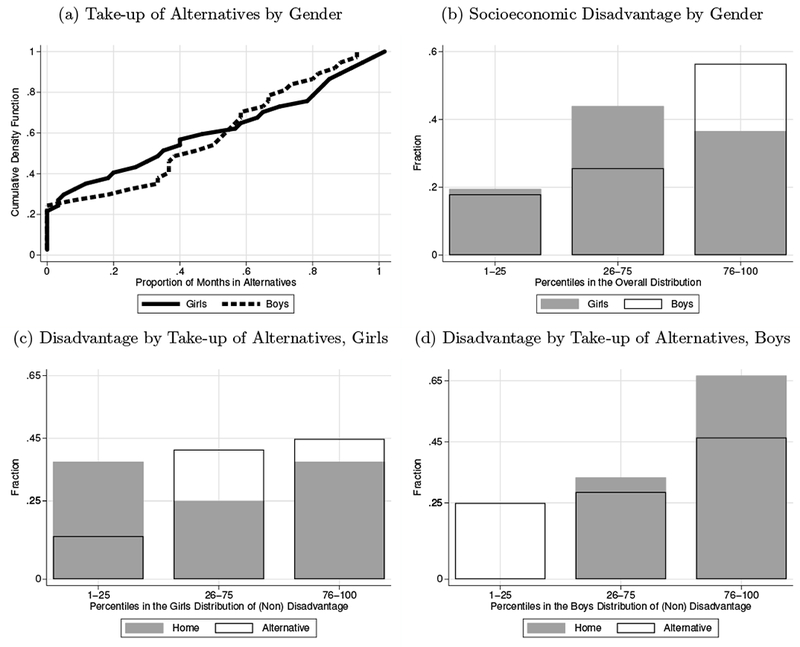

This difference is consistent with the interpretation that boys and girls faced different environments in their control group conditions, especially in their home environments.44,45 About the same percentage of control-group girls attended alternative formal childcare (73%) as did control-group boys (76%). See Figure 3a. No girls who stayed at home had working mothers at baseline while 23% of the girls who attended alternative formal childcare had mothers working at baseline. For boys, 14% of those who stayed at home had mothers working at baseline while 29% of those who attended alternative formal childcare had working mothers.

Figure 3:

Gender and Baseline Socioeconomic Disadvantage in the Control Group

Note: Panel (a) displays the cumulative distribution function of enrollment in alternatives by gender. Panel (b) displays how girls and boys separately fit into the overall (girls and boys pooled) distribution of socioeconomic disadvantage. Panel (c) displays how girls who did not enroll and girls who enrolled in alternatives fit into the overall female distribution of socioeconomic disadvantage. Panel (d) is analogous to Panel (c) for boys. Our measure of socioeconomic disadvantage is a latent of the following variables: Maternal age, education, and IQ, as well as number of siblings and HRI score.

Girls’ families were more resource-constrained compared to their male counterparts. Girls in the control group were raised in a more disadvantaged environment and many likely went to lower-quality preschools. Thus, as documented in Section 4, they benefited more from participation in ABC/CARE than boys when compared to the next best alternative as perceived by their parents.

To formally test the differences in home-life advantage between control-group girls and boys, we create an index of socioeconomic disadvantage at baseline using mother’s age, education, IQ, marital status, and employment, as well as number of children and father’s presence at home.46 We assess how girls and boys fit into the overall distribution of this latent measure in the control group. Boys are disproportionately more advantaged than girls (Panel 3b). In Panels 3c and 3d of Figure 3, we further assess socioeconomic disadvantage by gender of the child.

Table 5 uses our constructed measure of disadvantage to test the difference in baseline disadvantage across boys and girls. We reject the null hypothesis of a common distribution of socioeconomic disadvantage across girls and boys (at baseline).

Table 5:

Gender and Baseline Socioeconomic Disadvantage in the Control Group

| H0 | Rosenbaum (2005) p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | All Controls | |

| Male = female | 0.007 | |

| [2] | Males | |

| Alternative = Stay at Home | 0.006 | |

| [3] | Females | |

| Alternative = Stay at Home | 0.110 | |

Note: Row [1] displays an exact, non-parametric p-value for the null hypothesis that the control males and control females have the same level of disadvantage. Row [2] displays the same p-value for the null hypothesis that within males, those who attend alternative formal childcare and those who stay at home have the same level of disadvantage. Row [3] is analogous to Row [2] except for females. These tests are all based on a scalar measure of socioeconomic disadvantage (mother’s age, education, IQ, marital status, and employment, as well as number of siblings and father’s presence at home). Under the null hypotheses, the pairs with the closest distance in disadvantage would be comprised of one male and one female (for the comparison of males vs. females). Rejecting the null implies that the distributions are significantly different. Statistics significant at the 0.10 level are bolded.

Parents of more advantaged girls in the control group are more likely to send their daughters to alternative preschools. Parents of more advantaged boys in the control group are more likely to keep their sons at home. Thus, boys benefited more from treatment when compared to attending alternative formal childcare as opposed to staying at home where they faced better environments than girls. The opposite pattern holds for girls, although the differences between the treatment effects by mode of alternative childcare are smaller for girls than for boys.

As shown in Section 4, the childcare supplied by ABC/CARE increases maternal employment and family income in childhood. This effect is especially pronounced for the mothers of girls. Differentially higher employment of mothers induced by the program led to larger treatment effects on income for families of girls as a result of the childcare afforded mothers. HOME scores are also differentially enhanced for girls.

More fathers are present for boys. At baseline, this leads to more family resources for boys. Family income is higher for boys than girls after treatment despite the differential treatment effect in employment for the mothers of girls. While boys benefit from the greater presence of the father, the program does not appear to attract fathers to stay at home.

6. Summary and Conclusions

This paper examines gender differences in the percentage of treatment effects favoring men of an influential early childhood program targeted to disadvantaged children. Instead of analyzing gender differences in the number of program treatment effects one at a time and cherry-picking outcomes reporting only “significant” effects, we analyze aggregate summaries of treatment effects. We document that girls benefit more than boys in the sense that effect sizes are generally much bigger for girls than boys and more treatment effects are positive and statistically significant for girls.

We examine the source of the gender difference. They originate in differences in control conditions. Baseline family environments for girls are worse. At baseline, fathers of sons are more likely to be present at home than are fathers of daughters. This leads to more resources at baseline for boys. The more advantaged boys are more likely to stay at home. Differences in family environments explain why treatment effects are generally larger for males in comparison to alternative formal care than in comparison with staying at home.

For girls, the differences in outcomes across the two control conditions is not as stark. For both genders, treatment enhances family income through supporting maternal employment and improved HOME scores. The increments in family income are greater for girls, so are the increments in HOME scores. However, the level of family income after treatment is greater for boys despite the greater growth of family income for girls.

Our analysis has implications for the recent literature on gender differences in the consequences of childcare. Baker et al. (2008, 2015) establish harmful effects of childcare. Kottelenberg and Lehrer (2014) localize these harmful effects to boys. One interpretation of their findings is that young boys are more vulnerable to being taken away from home than are young girls.47 A rich literature supports the greater vulnerability of boys.48

Another interpretation, and the one emphasized in this paper, is that male home environments are generally better. This is consistent with the evidence of Dahl and Moretti (2008) who show that fathers are more likely to stay at home with the mother if a boy is born. This improves family income at baseline. Our evidence on baseline differences by gender is consistent with this interpretation. Girls benefit relatively more in terms of the gains in HOME scores and in family income.

Our data are too crude to distinguish sharply between these two interpretations. However, the weight of the evidence in this paper supports the latter interpretation. Baseline conditions need to be carefully accounted for in interpreting the sources of gender differences in treatment effects.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Policies for Action program, NICHD R37HD065072, the American Bar Foundation, the Buffett Early Childhood Fund, the Pritzker Children’s Initiative, NICHD R01HD054702, NIA R01AG042390, and by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG024968. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders or the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank Frances Campbell, Craig and Sharon Ramey, Margaret Burchinal, Carrie Bynum, Elizabeth Gunn, and the staff of the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill for the use of data and source materials from the Carolina Abecedarian Project and the Carolina Approach to Responsive Education. They also assisted with information on the implementation of the studied interventions. Years of partnership and collaboration have made this work possible. We thank Ruby Zhang for excellent research assistance. Collaborations with Andrés Hojman, Ganesh Karapakula, Yu Kyung Koh, Sylvi Kuperman, Stefano Mosso, Rodrigo Pinto, Joshua Shea, and Jake Torcasso on related work has strengthened the analysis in this paper. For helpful comments on various versions of the paper, we thank the editor, three anonymous referees, Stéphane Bonhomme, Flávio Cunha, Steven Durlauf, David Figlio, Marco Francesconi, Dana Goldman, Ganesh Karapakula, Sidharth Moktan, Rich Neimand, Tanya Rajan, Azeem Shaikh, Jeffrey Smith, Chris Taber, Matthew Tauzer, Ed Vytlacil, Jim Walker, and Matt Wiswall. We benefited from helpful comments received at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics in December, 2016, and at the University of Wisconsin, February, 2017. For information on childcare in North Carolina, we thank Richard Clifford and Sue Russell. The set of codes to replicate the computations in this paper are posted in a repository. Interested parties can request to download all the files. The address of the repository is https://github.com/jorgelgarcia/abccare-cba. To replicate the results in this paper, contact any of the authors, who will put you in contact with the appropriate individuals to obtain access to restricted data. The Appendix for this paper is posted on http://cehd.uchicago.edu/ABC_CARE.

Programs inspired by ABC/CARE have been (and are currently being) launched around the world. Sparling (2010) and Ramey et al. (2014) list numerous programs based on the ABC/CARE approach. The programs are: the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP)—eight different cities around the U.S. (Spiker et al., 1997); Early Head Start and Head Start. (Schneider and McDonald, 2007); John’s Hopkins Cerebral Palsy Study (Sparling, 2010); Classroom Literacy Interventions and Outcomes (CLIO) study (Sparling, 2010); Massachusetts Family Child Care Study (Collins et al., 2010); Healthy Child Manitoba Evaluation (Healthy Child Manitoba, 2015); Abecedarian Approach within an Innovative Implementation Framework (Jensen and Nielsen, 2016); and Building a Bridge into Preschool in Remote Northern Territory Communities in Australia (Scull et al., 2015). Educare programs are also based on ABC/CARE (Educare, 2014; Yazejian and Bryant, 2012).

Previous studies presenting treatment effects of ABC and CARE include Ramey et al. (1985); Clarke and Campbell (1998); Campbell et al. (2001, 2002); Anderson (2008); Campbell et al. (2008, 2014). Only Heckman (2006), Anderson (2008) and Campbell et al. (2014) separate treatment effects of early childhood programs by gender. Campbell et al. (2014) only use health data, and find that men are more affected by ABC/CARE than women. Anderson (2008) constructs factors using data up to the age-21 collection and finds that women benefit more than men in terms of his constructed factors, but does not use the crime, health, and employment data used in this paper.

The exact non-parametric test is described more precisely later in the paper.

This finding of females benefitting more than males (except in health) is consistent with previous work studying the gender differences in early childhood education. We survey the literature in Appendix C.1. See Elango et al. (2016) for a discussion of the main findings from the literature on early childhood education. Not reporting gender differences is a common practice. Examples include Schweinhart et al. (2005); Bernal and Keane (2011); Cascio and Schanzenbach (2013); Bitler et al. (2014); Kline and Walters (2016). There are some exceptions: Heckman (2005); Anderson (2008); Heckman et al. (2010); Campbell et al. (2014); García et al. (2018).

We do not have precise measures of the quality of individual alternative preschools, although we do know that girls were more disadvantaged. This implies that their families would have fewer resources to spend on higher-quality alternative preschools.

Burchinal et al. (1989) show that the quality of the available alternatives was of lower quality than the treatment offered through ABC/CARE. We supplement this evidence with historical records showing that even the alternatives that followed state and federal standards of the era were of lower quality than ABC/CARE as measured by concrete measures such as child-staff ratios. We provide more detail on the quality of ABC/CARE and the alternative options in Section 2 and Appendix A.

See Appendix A.2 for the full list of the determinants of HRI (Ramey and Smith, 1977; Wasik et al., 1990; Ramey and Campbell, 1991).

During ABC and CARE, the Learning Games curriculum was developed and refined (Sparling and Lewis, 1979, 1984).

These aspects of the program relate to structural quality rather than process quality, i.e., the daily experiences of the children (Thomason and La Paro, 2009). Aspects of structural quality, including low child-teacher ratios, small group sizes, and teacher education, are often associated with high process quality (Phillipsen et al., 1997). Recent studies find that curricula and professional development are highly correlated with process quality. This is especially true if the curricula and professional development are informed by knowledge of child development (Slot et al., 2015). Although measures of process quality (e.g., measures of teacher-child interactions) are not available for the ABC/CARE subjects, the curricula and professional development offerings were intensive, especially compared to standards of that era (Burchinal et al., 1989).

Campbell et al. (2014) and Burchinal et al. (2006) test and do not reject the hypothesis of no treatment effects for this additional component of CARE.

We do not know the original pairs.

The modest sample size after accounting for dropouts, especially after dividing the sample by male and female, is unavoidable. No datasets have the experimental design and longitudinal data collection of ABC/CARE with a large sample. Future research should repeat these analyses in larger studies (e.g., the Infant Health and Development Program) as the subjects continue to age.

See Heckman et al. (2000) and Kline and Walters (2016) on the issue of substitution bias in social experiments.

See Figure A.7 in Appendix A.5.

Appendix A.5.1 shows this and discusses the standards of the day (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1968; North Carolina General Assembly, 1971; Ramey et al., 1977; Ramey and Campbell, 1979; Ramey et al., 1982; Burchinal et al., 1997)

Time-use data are not available.

According to Ramey et al. (1984), there was only one eligible mother who refused to participate in the randomization.

This is an example of control-group subjects of a social experiment finding a treatment substitute. See Heckman et al. (2000) for methodological solutions and an example of implementation.

We discuss cases of attrition during the program in Appendix A.

This categorization is consistent with Figure 1b. Once parents decided to enroll their children in alternative preschools, the children tended to stay enrolled up to age 5.

For the distinction between fixing and conditioning, see Haavelmo (1943) and Heckman and Pinto (2015).

To select adequate variables for matching, we conduct goodness of fit tests to find the most predictive set of baseline characteristics subject to penalty for adding parameters. This procedure is fully explained in Appendix D.

In Appendix D we present an exhaustive list of treatment effects correcting the p-values using the step-down procedure in Romano and Wolf (2016).

All but 5% of the outcomes we study can be ranked in this fashion. See Appendix D for a discussion.

Campbell et al. (2014) establish the validity of asymptotic approximations for the ABC sample.

In this case, we perform a “double bootstrap” procedure to first determine significant treatment effects at 10% level and then calculate the standard error of the count.

In Appendix D, we present yet another alternative. We calculate a latent measure, using principal component analysis, of the set of outcomes within a block and perform inference on this latent measure. This analysis also points to beneficial effects of the program.

The exact p-values are very similar. We display asymptotic p-values for computational simplicity.

In Appendix D, we show the effects on mother’s employment individually. Table D.56 shows that the effect on females is large across ages compared to those who stayed at home. This is also seen for males (Table D.40), although the estimated effect on males does not survive adjustments for multiple hypothesis testing (Table D.88). The female results are robust (Table D.104). This goes against the findings of Havnes and Mogstad (2011), who find that subsidized child care does not increase maternal labor supply, but is consistent with several other studies finding an increase in maternal labor supply as a result of subsidized child care (Bauernschuster and Schlotter, 2015; Bettendorf et al., 2015; Geyer et al., 2015; Brilli et al., 2016).

The Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment (HOME) was collected on the ABC/CARE subjects annually until age 5 and at age 8. To administer it, a trained researcher visited homes to observe how the mother and child interacted, using a rubric of items that capture different dimensions of parent-child interactions. Up to 3 years of age, the HOME score measures maternal warmth, absence of punishment, organization of the environment, provision of appropriate toys, maternal involvement with child, and opportunity for variety. From 3 to 5 years of age, the HOME score measures stimulation through toys and experiences, stimulation of mature behavior, physical and language environment, avoidance of restriction, pride and affection, masculine stimulation, and independence from parental control. At 8 years of age, the HOME score measures organization of a stable environment, developmental stimulation, quality of the language environment, need gratification, fostering maturity, emotional climate, breadth of experience, aspects of physical environment, and play materials (Bradley and Caldwell, 1977).

One advantage of the benefit/cost analysis is that it intrinsically accounts for extreme values. For example, individual crimes are weighed by their social cost instead of the average crime being weighed.

Given the preponderance of single parent female-headed families, “paternal income” is effectively “maternal income.”

The reported Rosenbaum p-values are likely biased downwards because we treat individual items within categories as independently distributed, likely exaggerating degrees of freedom.

We summarize previous research on gender differences in Table C.1.

See Appendix D for estimates of individual treatment effects and additional specifications of combining functions.

Disaggregating by outcomes, by category, gender, and mode of childcare for controls produces a noisy pattern that is broadly consistent in Figure 2.

Table A.4 summarizes the baseline characteristics by gender and mode of childcare.

An alternative explanation is greater adverse reaction among some boys to being withdrawn from the home environment (García et al., 2019). We discuss this possibility at greater length in Section 6.

This index is distinct from HRI.

See García et al. (2019).

Contributor Information

Jorge Luis García, John E. Walker Department of Economics, Clemson University, 228 Sirrine Hall, Clemson, SC 29634, Phone: 773-449-0744, jorge.ggmenendez@gmail.com.

James J. Heckman, Center for the Economics of Human Development, University of Chicago, 1126 East 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, Phone: 773-702-0634, jjh@uchicago.edu

Anna L. Ziff, Department of Economics, Duke University, 213 Social Sciences Building, 419 Chapel Drive, Box 90097, Durham, NC 27708, Phone: 734-277-7379, anna.ziff@duke.edu

References

- Almlund M, Duckworth AL, Heckman JJ, and Kautz T (2011). Personality psychology and economics In Hanushek EA, Machin S, and Wößmann L (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education, Volume 4, Chapter 1, pp. 1–181. Amsterdam: Elsevier B. V. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ML (2008, December). Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool and Early Training Projects. Journal of the American Statistical Association 103(484), 1481–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Apgar V (1966). The newborn (APGAR) scoring system: Reflections and advice. Pediatric Clinics of North America 13(3), 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Gruber J, and Milligan K (2008, August). Universal childcare, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy 116 (4), 709–745. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Gruber J, and Milligan K (2015, September). Non-cognitive deficits and young adult outcomes: The long-run impacts of a universal child care program Working Paper 21571, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bauernschuster S and Schlotter M (2015). Public child care and mothers’ labor supply—evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics 123, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal R and Keane MP (2011, July). Child care choices and children’s cognitive achievement: The case of single mothers. Journal of Labor Economics 29(3), 459–512. [Google Scholar]

- Bettendorf LJ, Jongen EL, and Muller P (2015). Childcare subsidies and labour supply — evidence from a large Dutch reform. Labour Economics 36, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler MP, Hoynes HW, and Domina T (2014). Experimental evidence on distributional effects of Head Start Working Paper 20434, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH and Caldwell BM (1977, March). Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment: A validation study of screening efficiency. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 81 (5), 417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilli Y, Del Boca D, and Pronzato CD (2016). Does child care availability play a role in maternal employment and childrens development? evidence from Italy. Review of Economics of the Household 14 (1), 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Campbell FA, Bryant DM, Wasik BH, and Ramey CT (1997, October). Early intervention and mediating processes in cognitive performance of children of low-income African American families. Child Development 68 (5), 935–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Lee M, and Ramey CT (1989). Type of day-care and preschool intellectual development in disadvantaged children. Child Development 60 (1), 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Nelson L, and Poe M (2006). Iv. growth curve analysis: An introduction to various methods for analyzing longitudinal data. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 71 (3), 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Conti G, Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Pungello EP, and Pan Y (2014). Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science 343(6178), 1478–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Pungello EP, Miller-Johnson S, Burchinal M, and Ramey CT (2001, March). The development of cognitive and academic abilities: Growth curves from an early childhood educational experiment. Developmental Psychology 37(2), 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA and Ramey CT (1995, Winter). Cognitive and school outcomes for high-risk African-American students at middle adolescence: Positive effects of early intervention. American Educational Research Journal 32 (4), 743–772. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Ramey CT, Pungello E, Sparling J, and Miller-Johnson S (2002). Early childhood education: Young adult outcomes from the Abecedarian Project. Applied Developmental Science 6(1), 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Wasik B, Pungello E, Burchinal M, Barbarin O, Kainz K, Sparling J, and Ramey C (2008). Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23(4), 452–466. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio EU and Schanzenbach DW (2013, Fall). The impacts of expanding access to high-quality preschool education. The Brookings Institution 47(2), 127–192. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SH and Campbell FA (1998). Can intervention early prevent crime later? The Abecedarian Project compared with other programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 13(2), 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Goodson BD, Luallen J, Fountain AR, Checkoway A, and Abt Associates Inc. (2010, June). Evaluation of child care subsidy strategies: Massachusetts Family Child Care study Technical Report OPRE 2011-1, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl GB and Moretti E (2008). The demand for sons. The Review of Economic Studies 75(4), 1085–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (1968). Federal interagency day care requirements, pursuant to Sec. 522 (D) of the Economic Opportunity Act Technical report, U.S. Department of Labor, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Derigs U (1988). Solving non-bipartite matching problems via shortest path techniques. Annals of Operations Research 13(1), 225–61. [Google Scholar]

- Educare (2014). A national research agenda for early education Technical report, Educare Learning Network Research & Evaluation Committee, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Elango S, García JL, Heckman JJ, and Hojman A (2016). Early childhood education In Moffitt RA (Ed.), Economics of Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States, Volume 2, Chapter 4, pp. 235–297. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- García JL, Heckman JJ, Leaf DE, and Prados MJ (2018). Quantifying the life-cycle benefits of a prototypical early childhood program. Under review at the Journal of Political Economy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García JL, Heckman JJ, and Ziff AL (2019). Early childhood education and crime. Infant Mental Health Journal 40(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer J, Haan P, and Wrohlich K (2015). The effects of family policy on maternal labor supply: Combining evidence from a structural model and a quasi-experimental approach. Labour Economics 36, 84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Golding P and Fitzgerald HE (2017). Psychology of boys at risk: Indicators from 0–5. Infant Mental Health Journal 38 (1), 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavelmo T (1943, January). The statistical implications of a system of simultaneous equations. Econometrica 11 (1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Havnes T and Mogstad M (2011, December). Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. Journal of Public Economics 95(11–12), 1455–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Child Manitoba (2015, April). Starting early, starting strong: A guide for play-based early learning in Manitoba: Birth to six Technical report, Healthy Child Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ (2005). Invited comments In Schweinhart LJ, Montie J, Xiang Z, Barnett WS, Belfield CR, and Nores M (Eds.), Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40, pp. 229–233. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press. Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ (2006, June). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312 (5782), 1900–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Hohmann N, Smith J, and Khoo M (2000, May). Substitution and dropout bias in social experiments: A study of an influential social experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(2), 651–694. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Savelyev PA, and Yavitz AQ (2010, July). Analyzing social experiments as implemented: A reexamination of the evidence from the HighScope Perry Preschool Program. Quantitative Economics 1 (1), 1–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ and Pinto R (2015). Causal analysis after Haavelmo. Econometric Theory 31 (1), 115–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbens GW and Angrist JD (1994, March). Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 62(2), 467–475. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen B and Nielsen M (2016). Abecedarian programme, within an innovative implementation framework (APIIF). A pilot study. Website, http://pure.au.dk/portal/en/projects/abecedarian-programme-within-an-innovative-implementation-framework-apiif-a-pilot-study(8d4da9a9-f2ff-44db-87cc-1278d1e7006c).html (Accessed 8/1/2016).

- Kline P and Walters C (2016). Evaluating public programs with close substitutes: The case of Head Start. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131 (4), 1795–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelenberg MJ and Lehrer SF (2014, August). The gender effects of universal child care in Canada: Much ado about boys? Unpublished manuscript, Department of Economics, Queen’s University. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis PC (1936). On the generalized distance in statistics. Proceedings of the National Institute of Sciences of India 2(1), 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina General Assembly (1971). Chapter 803, House bill 100. In North Carolina General Assembly 1971 Session, North Carolina: An Act to protect children through licensing of day-care facilities and other limited regulation. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipsen LC, Burchinal MR, Howes C, and Cryer D (1997). The prediction of process quality from structural features of child care. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 12 (3), 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey C, Yeates KO, and Short EJ (1984, October). The plasticity of intellectual development: Insights from preventive intervention. Child Development 55(5), 1913–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Bryant DM, Sparling JJ, and Wasik BH (1985). Project CARE: A comparison of two early intervention strategies to prevent retarded development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 5(2), 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT and Campbell FA (1979, February). Compensatory education for disadvantaged children. The School Review 87(2), 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT and Campbell FA (1991). Poverty, early childhood education and academic competence: The Abecedarian experiment In Houston AC (Ed.), Children in Poverty: Child Development and Public Policy, Chapter 8, pp. 190–221. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Collier AM, Sparling JJ, Loda FA, Campbell FA, Ingram DA, and Finkelstein NW (1976). The Carolina Abecedarian Project: A longitudinal and multidisciplinary approach to the prevention of developmental retardation In Tjossem T (Ed.), Intervention Strategies for High-Risk Infants and Young Children, pp. 629–655. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Holmberg MC, Sparling JH, and Collier AM (1977). An introduction to the Carolina Abecedarian Project In Caldwell BM and Stedman DJ (Eds.), Infant Education: A Guide for Helping Handicapped Children in the First Three Years, Chapter 7, pp. 101–121. New York: Walker and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, McGinness GD, Cross L, Collier AM, and Barrie-Blackley S (1982). The Abecedarian approach to social competence: Cognitive and linguistic intervention for disadvantaged preschoolers In Borman KM (Ed.), The Social Life of Children in a Changing Society, Chapter 7, pp. 145–174. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT and Smith BJ (1977, January). Assessing the intellectual consequences of early intervention with high-risk infants. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 81 (4), 318–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Sparling JJ, and Ramey SL (2012). Abecedarian: The Ideas, the Approach, and the Findings (1 ed.). Los Altos, CA: Sociometrics Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey SL, Ramey CT, and Lanzi RG (2014). Interventions for students from impoverished environments In Mascolo JT, Alfonso VC, and Flanagan DP (Eds.), Essentials of Planning, Selecting and Tailoring Interventions for Unique Learners, pp. 415–48. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Romano JP and Wolf M (2016). Efficient computation of adjusted p-values for resampling-based stepdown multiple testing. Statistics and Probability Letters 113, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR (2005). An exact distribution-free test comparing two multivariate distributions based on adjacency. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 67(4), 515–530. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B and McDonald S-K (Eds.) (2007). Scale-Up in Education, Volume 1: Ideas in Principle Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN (2017, Jan-Feb). All our sons: The developmental neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of boys at risk. Infant Mental Health Journal 38(1), 15–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinhart LJ, Montie J, Xiang Z, Barnett WS, Belfield CR, and Nores M (2005). Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40, Volume 14 of Monographs of the HighScope Educational Research Foundation. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scull J, Hattie J, Page J, Sparling J, Tayler C, King A, Nossar V, Piers-Blundell A, and Ramey C (2015). Building a bridge into preschool in remote Northern Territory communities.

- Slot PL, Leseman PP, Verhagen J, and Mulder H (2015). Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in Dutch early childhood education and care settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 33(4th Quarter), 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sparling J (2010). Highlights of research findings from the Abecedarian studies Technical report, Teaching Strategies, Inc., Center on Health and Education, Georgetown University, and FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Sparling J and Lewis I (1979). LearningGames for the First Three Years: A Guide to Parent/Child Play. New York: Walker and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sparling J and Lewis I (1984). LearningGames for Threes and Fours. New York: Walker and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Spiker D, Haynes CW, and Gross RT (Eds.) (1997). Helping Low Birth Weight, Premature Babies: The Infant Health and Development Program. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason AC and La Paro KM (2009). Measuring the quality of teacherchild interactions in toddler child care. Early Education and Development 20 (2), 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik BH, Ramey C, Bryant DM, and Sparling JJ (1990, December). A longitudinal study of two early intervention strategies: Project CARE. Child Development 61 (6), 1682–1696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazejian N and Bryant DM (2012). Educare implementation study findings Technical report, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Chapel Hill, NC. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.